Biography:Yukio Mishima

Yukio Mishima | |

|---|---|

三島由紀夫 | |

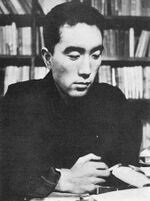

Mishima in 1956 | |

| Born | Kimitake Hiraoka Nagazumi-cho 2-chome, Yotsuya-ku, Tokyo City, Tokyo Prefecture, Empire of Japan (present-day Yotsuya 4-chome, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, Japan )[1] |

| Died | 25 November 1970 (aged 45) JGSDF Camp Ichigaya Ichigaya Honmura-chō, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan |

| Cause of death | Suicide by Seppuku |

| Resting place | Tama Cemetery, Tokyo |

| Alma mater | Faculty of Law, University of Tokyo |

| Occupation |

|

Notable work | Confessions of a Mask, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, The Sea of Fertility |

| Signature | |

| |

Yukio Mishima[lower-alpha 1] (三島 由紀夫 Mishima Yukio, 14 January 1925 – 25 November 1970), born Kimitake Hiraoka (平岡 公威 Hiraoka Kimitake), was a Japanese author, poet, playwright, actor, model, Shintoist, nationalist, and founder of the Tatenokai (楯の会, "Shield Society"), an unarmed civilian militia. Mishima is considered one of the most important Japanese authors of the 20th century. He was considered for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1968, but the award went to his countryman and benefactor Yasunari Kawabata.[6] His works include the novels Confessions of a Mask (仮面の告白, Kamen no kokuhaku) and The Temple of the Golden Pavilion (金閣寺, Kinkaku-ji), and the autobiographical essay Sun and Steel (太陽と鉄, Taiyō to tetsu). Mishima's work is characterized by "its luxurious vocabulary and decadent metaphors, its fusion of traditional Japanese and modern Western literary styles, and its obsessive assertions of the unity of beauty, eroticism and death",[7] according to author Andrew Rankin.

Mishima's political activities made him a controversial figure, which he remains in modern Japan.[8][9][10][11] From his mid-30s, Mishima's right-wing ideology was increasingly revealed. He was proud of the traditional culture and spirit of Japan, and opposed what he saw as western-style materialism, along with Japan's postwar democracy, globalism, and communism, worrying that by embracing these ideas the Japanese people would lose their "national essence" (kokutai) and their distinctive cultural heritage (Shinto and Yamato-damashii) to become a "rootless" people.[12][13][14][15] Mishima formed the Tatenokai for the avowed purpose of restoring sacredness and dignity to the Emperor of Japan.[13][14][15] On 25 November 1970, Mishima and four members of his militia entered a military base in central Tokyo, took its commandant hostage, and unsuccessfully tried to inspire the Japan Self-Defense Forces to rise up and overthrow Japan's 1947 Constitution (which he called "a constitution of defeat").[15][12] After his speech and screaming of "Long live the Emperor!", he committed seppuku.

Life and work

Early life

Kimitake Hiraoka (平岡公威 Hiraoka Kimitake), later known as Yukio Mishima (三島由紀夫 Mishima Yukio), was born in Nagazumi-cho, Yotsuya-ku of Tokyo City (now part of Yotsuya, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo). He chose his pen name when he was 16.[16] His father was Azusa Hiraoka (平岡梓), a government official in the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce,[17] and his mother, Shizue (倭文重), was the daughter of the 5th principal of the Kaisei Academy. Shizue's father, Kenzō Hashi (橋健三), was a scholar of the Chinese classics, and the Hashi family had served the Maeda clan for generations in Kaga Domain. Mishima's paternal grandparents were Sadatarō Hiraoka (平岡定太郎), the third Governor-General of Karafuto Prefecture, and Natsuko (family register name: Natsu) (平岡なつ). Mishima received his birth name Kimitake (公威, also read Kōi in on-yomi) in honor of Furuichi Kōi (古市公威) who was a benefactor of Sadatarō.[18] He had a younger sister, Mitsuko (美津子), who died of typhus in 1945 at the age of 17, and a younger brother, Chiyuki (千之).[19][1]

Mishima's childhood home was a rented house, though a fairly large two-floor house that was the largest in the neighborhood. He lived with his parents, siblings and paternal grandparents, as well as six maids, a houseboy, and a manservant. His grandfather was in debt, so there were no remarkable household items left on the first floor.[20]

Mishima's early childhood was dominated by the presence of his grandmother, Natsuko, who took the boy and separated him from his immediate family for several years.[21] She was the granddaughter of Matsudaira Yoritaka (松平頼位), the daimyō of Shishido, which was a branch domain of Mito Domain in Hitachi Province;[lower-alpha 2] therefore, Mishima was a direct descendant of the founder of the Tokugawa Shogunate, Tokugawa Ieyasu (徳川家康), through his grandmother.[22][23][24] Natsuko's father, Nagai Iwanojō (永井岩之丞), had been a Supreme Court justice, and Iwanojō's adoptive father, Nagai Naoyuki (永井尚志), had been a bannerman of the Tokugawa House during the Bakumatsu.[22] Natsuko had been raised in the household of Prince Arisugawa Taruhito, and she maintained considerable aristocratic pretensions even after marrying Sadatarō, a bureaucrat who had made his fortune in the newly opened colonial frontier in the north, and who eventually became Governor-General of Karafuto Prefecture on Sakhalin Island.[25] Sadatarō's father, Takichi Hiraoka (平岡太吉), and grandfather, Tazaemon Hiraoka (平岡太左衛門), had been farmers.[22][lower-alpha 3] Natsuko was prone to violent outbursts, which are occasionally alluded to in Mishima's works,[27] and to whom some biographers have traced Mishima's fascination with death.[28] She did not allow Mishima to venture into the sunlight, engage in any kind of sport, or play with other boys. He spent much of his time either alone or with female cousins and their dolls.[29][27]

Mishima returned to his immediate family when he was 12. His father Azusa had a taste for military discipline, and worried Natsuko's style of childrearing was too soft. When Mishima was an infant, Azusa employed parenting tactics such as holding Mishima up to the side of a speeding train. He also raided his son's room for evidence of an "effeminate" interest in literature, and often ripped his son's manuscripts apart.[30] Although Azusa forbade him to write any further stories, Mishima continued to write in secret, supported and protected by his mother, who was always the first to read a new story.[30]

When Mishima was 13, Natsuko took him to see his first Kabuki play: Kanadehon Chūshingura, an allegory of the story of the 47 Rōnin. He was later taken to his first Noh play (Miwa, a story featuring Amano-Iwato) by his maternal grandmother Tomi Hashi (橋トミ). From these early experiences, Mishima became addicted to Kabuki and Noh. He began attending performances every month and grew deeply interested in these traditional Japanese dramatic art forms.[31]

Schooling and early works

Mishima was enrolled at the age of six in the elite Gakushūin, the Peers' School in Tokyo, which had been established in the Meiji period to educate the Imperial family and the descendants of the old feudal nobility.[32] At 12, Mishima began to write his first stories. He read myths (Kojiki, Greek mythology, etc.) and the works of numerous classic Japanese authors as well as Raymond Radiguet, Jean Cocteau, Oscar Wilde, Rainer Maria Rilke, Thomas Mann, Friedrich Nietzsche, Charles Baudelaire, l'Isle-Adam, and other European authors in translation. He also studied German. After six years at school, he became the youngest member of the editorial board of its literary society. Mishima was attracted to the works of the Japanese poet Shizuo Itō (伊東静雄 Itō Shizuo), poet and novelist Haruo Satō (佐藤春夫), and poet Michizō Tachihara (立原道造), who inspired Mishima's appreciation of classical Japanese waka poetry. Mishima's early contributions to the Gakushūin literary magazine Hojinkai-zasshi (輔仁会雑誌) included haiku and waka poetry before he turned his attention to prose.[33]

In 1941, at the age of 16, Mishima was invited to write a short story for the Hojinkai-zasshi, and he submitted Forest in Full Bloom (花ざかりの森 Hanazakari no Mori), a story in which the narrator describes the feeling that his ancestors somehow still live within him. The story uses the type of metaphors and aphorisms that became Mishima's trademarks.[lower-alpha 4] He mailed a copy of the manuscript to his Japanese teacher Fumio Shimizu (清水文雄) for constructive criticism. Shimizu was so impressed that he took the manuscript to a meeting of the editorial board of the prestigious literary magazine Bungei Bunka (文藝文化), of which he was a member. At the editorial board meeting, the other board members read the story and were very impressed; they congratulated themselves for discovering a genius and published it in the magazine. The story was later published as a limited book edition (4,000 copies) in 1944 due to a wartime paper shortage. Mishima had it published as a keepsake to remember him by, as he assumed that he would die in the war.[36][30]

In order to protect him from potential backlash from Azusa, Shimizu and the other editorial board members coined the pen-name Yukio Mishima.[37] They took "Mishima" from Mishima Station, which Shimizu and fellow Bungei Bunka board member Hasuda Zenmei passed through on their way to the editorial meeting, which was held in Izu, Shizuoka. The name "Yukio" came from yuki (雪), the Japanese word for "snow," because of the snow they saw on Mount Fuji as the train passed.[37] In the magazine, Hasuda praised Mishima's genius as follows:

This youthful author is a heaven-sent child of eternal Japanese history. He is much younger than we are, but has arrived on the scene already quite mature.[38]

Hasuda, who became something of a mentor to Mishima, was an ardent nationalist and a fan of Motoori Norinaga (1730–1801), a scholar of kokugaku from the Edo period who preached Japanese traditional values and devotion to the Emperor.[39] Hasuda had previously fought for the Imperial Japanese Army in China in 1938, and in 1943 he was recalled to active service for deployment as a first lieutenant in the Southeast Asian theater.[40] At a farewell party thrown for Hasuda by the Bungei Bunka group, Hasuda offered the following parting words to Mishima:

I have entrusted the future of Japan to you.

According to Mishima, these words were deeply meaningful to him, and had a profound effect on the future course of his life.[41][42][43]

Later in 1941, Mishima wrote in his notebook an essay about his deep devotion to Shintō, titled The Way of the Gods (惟神之道 Kannagara no michi).[44] Mishima's story The Cigarette (煙草 Tabako), published in 1946, describes a homosexual love he felt at school and being teased from members of the school's rugby union club because he belonged to the literary society. Another story from 1954, The Boy Who Wrote Poetry (詩を書く少年 Shi o kaku shōnen), was also based on Mishima's memories of his time at Gakushūin Junior High School.[45]

On 9 September 1944, Mishima graduated Gakushūin High School at the top of the class, and became a graduate representative.[46][47] Emperor Hirohito was present at the graduation ceremony, and Mishima later received a silver watch from the Emperor at the Imperial Household Ministry.[46][47][48][49]

On 27 April 1944, during the final years of World War II, Mishima received a draft notice for the Imperial Japanese Army and barely passed his conscription examination on 16 May 1944, with a less desirable rating of "second class" conscript. He had a cold during his medical check on convocation day (10 February 1945), and the young army doctor misdiagnosed Mishima with tuberculosis, declared him unfit for service, and sent him home.[50][30] Scholars have argued that Mishima's failure to receive a "first class" rating on his conscription exam (reserved only for the most physically fit recruits), in combination with the illness which led him to be erroneously declared unfit for duty, contributed to an inferiority complex over his frail constitution that later led to his obsession with physical fitness and bodybuilding.[51]

The day before his failed medical exam, Mishima wrote a farewell message to his family, ending with the words "Long live the Emperor!" (天皇陛下万歳 Tennō heika banzai), and prepared clippings of his hair and nails to be kept as mementos by his parents.[30][52] The troops of the unit that Mishima was supposed to have joined were sent to the Philippines , where most of them were killed.[50] Mishima's parents were ecstatic that he did not have to go to war, but Mishima's mood was harder to read; Mishima's mother overheard him say he wished he could have joined a "Special Attack" (特攻, tokkō) unit.[30] Around that time, Mishima admired kamikaze pilots and other "special attack" units in letters to friends and private notes.[46][53][54]

Mishima was deeply affected by Emperor Hirohito's radio broadcast announcing Japan's surrender on 15 August 1945, and vowed to protect Japanese cultural traditions and help rebuild Japanese culture after the destruction of the war.[55] He wrote in his diary:

Only by preserving Japanese irrationality will we be able contribute to world culture 100 years from now.[56]

On 19 August, four days after Japan's surrender, Mishima's mentor Zenmei Hasuda, who had been drafted and deployed to the Malay peninsula, shot and killed a superior officer for criticizing the Emperor before turning his pistol on himself. Mishima learned of the incident a year later and contributed poetry in Hasuda's honor at a memorial service in November 1946.[57] On 23 October 1945 (Showa 20), Mishima's beloved younger sister Mitsuko died suddenly at the age of 17 from typhoid fever by drinking untreated water.[30][58] Around that same time he also learned that Kuniko Mitani (三谷邦子), a classmate's sister whom he had hoped to marry, was engaged to another man.[59][60][lower-alpha 5] These tragic incidents in 1945 became a powerful motive force in inspiring Mishima's future literary work.[62]

At the end of the war, his father Azusa "half-allowed" Mishima to become a novelist. He was worried that his son could actually become a professional novelist, and hoped instead that his son would be a bureaucrat like himself and Mishima's grandfather Sadatarō. He advised his son to enroll in the Faculty of Law instead of the literature department.[30] Attending lectures during the day and writing at night, Mishima graduated from the University of Tokyo in 1947. He obtained a position in the Ministry of the Treasury and seemed set up for a promising career as a government bureaucrat. However, after just one year of employment Mishima had exhausted himself so much that his father agreed to allow him to resign from his post and devote himself to writing full time.[30]

In 1945, Mishima began the short story A Story at the Cape (岬にての物語, Misaki nite no Monogatari) and continued to work on it through the end of World War II. After the war, it was praised by Shizuo Itō whom Mishima respected.[63]

Post-war literature

After Japan's defeat in World War II, the country was occupied by the U.S.-led Allied Powers. At the urging of the occupation authorities, many people who held important posts in various fields were purged from public office. The media and publishing industry were also censored, and were not allowed to engage in forms of expression reminiscent of wartime Japanese nationalism.[lower-alpha 6] In addition, literary figures, including many of those who had been close to Mishima before the end of the war, were branded "war criminal literary figures". Some people denounced them and converted to left-wing politics, whom Mishima criticized as "opportunists" in his letters to friends.[66][67][68] Some prominent literary figures became leftists, and joined the Communist Party as a reaction against wartime militarism and writing socialist realist literature that might support the cause of socialist revolution.[69] Their influence had increased in the Japanese literary world following the end of the war, which Mishima found difficult to accept. Although Mishima was just 20 years old at this time, he worried that his type of literature, based on the 1930s Japanese Romantic School (日本浪曼派, "Nihon Rōman Ha"), had already become obsolete.[31]

Mishima had heard that famed writer Yasunari Kawabata had praised his work before the end of the war. Uncertain of who else to turn to, Mishima took the manuscripts for The Middle Ages (中世 Chūsei) and The Cigarette (煙草 Tabako) with him, visited Kawabata in Kamakura, and asked for his advice and assistance in January 1946.[31] Kawabata was impressed, and in June 1946, following Kawabata's recommendation, "The Cigarette" was published in the new literary magazine Ningen (人間, "Humanity"), followed by "The Middle Ages" in December 1946.[70] "The Middle Ages" is set in Japan's historical Muromachi Period and explores the motif of shudō (衆道, man-boy love) against a backdrop of the death of the ninth Ashikaga shogun Ashikaga Yoshihisa (足利義尚) in battle at the age of 25, and his father Ashikaga Yoshimasa (足利義政)'s resultant sadness. The story features the fictional character Kikuwaka, a beautiful teenage boy who was beloved by both Yoshihisa and Yoshimasa, who fails in an attempt to follow Yoshihisa in death by committing suicide. Thereafter, Kikuwaka devotes himself to spiritualism in an attempt to heal Yoshimasa's sadness by allowing Yoshihisa's ghost to possess his body, and eventually dies in a double-suicide with a miko (巫女, shrine maiden) who falls in love with him. Mishima wrote the story in an elegant style drawing upon medieval Japanese literature and the Ryōjin Hishō, a collection of medieval imayō songs. This elevated writing style and the homosexual motif suggest the germ of Mishima's later aesthetics.[70] Later in 1948 Kawabata, who praised this work, published an essay describing his experience of falling in love for the first time with a boy two years his junior.[71]

In 1946, Mishima began his first novel, Thieves (盗賊 Tōzoku), a story about two young members of the aristocracy drawn towards suicide. It was published in 1948, and placed Mishima in the ranks of the Second Generation of Postwar Writers. The following year, he published Confessions of a Mask (仮面の告白 Kamen no kokuhaku), a semi-autobiographical account of a young homosexual man who hides behind a mask to fit into society. The novel was extremely successful and made Mishima a celebrity at the age of 24. Around 1949, Mishima also published a literary essay about Kawabata, for whom he had always held a deep appreciation, in Kindai Bungaku (近代文学).[72]

Mishima enjoyed international travel. In 1952, he took a world tour and published his travelogue as The Cup of Apollo (アポロの杯 Aporo no Sakazuki). He visited Greece during his travels, a place which had fascinated him since childhood. His visit to Greece became the basis for his 1954 novel The Sound of Waves (潮騒 Shiosai), which drew inspiration from the Greek legend of Daphnis and Chloe. The Sound of Waves, set on the small island of "Kami-shima" where a traditional Japanese lifestyle continued to be practiced, depicts a pure, simple love between a fisherman and a female pearl and abalone diver (海女 ama). Although the novel became a best-seller, leftists criticized it for "glorifying old-fashioned Japanese values", and some people began calling Mishima a "fascist".[73][74][75] Looking back on these attacks in later years, Mishima wrote, "The ancient community ethics portrayed in this novel were attacked by progressives at the time, but no matter how much the Japanese people changed, these ancient ethics lurk in the bottom of their hearts. We have gradually seen this proven to be the case."[76]

Mishima made use of contemporary events in many of his works. The Temple of the Golden Pavilion (金閣寺, Kinkaku-ji), published in 1956, is a fictionalization of the burning down of the Kinkaku-ji Buddhist temple in Kyoto in 1950 by a mentally disturbed monk.[77]

In 1959, Mishima published the artistically ambitious novel Kyōko no Ie (Kyōko's house) (鏡子の家 Kyōko no Ie). The novel tells the interconnected stories of four young men who represented four different facets of Mishima's personality. His athletic side appears as a boxer, his artistic side as a painter, his narcissistic, performative side as an actor, and his secretive, nihilistic side as a businessman who goes through the motions of living a normal life while practicing "absolute contempt for reality". According to Mishima, he was attempting to describe the time around 1955 in the novel, when Japan was entering into its era of high economic growth and the phrase "The postwar is over" was prevalent.[lower-alpha 7] Mishima explained, "Kyōko no Ie is, so to speak, my research into the nihilism within me."[79][80] Although the novel was well received by a small number of critics from the same generation as Mishima and sold 150,000 copies in a month, it was widely panned in broader literary circles,[81][82] and was rapidly branded as Mishima's first "failed work".[83][82] It was Mishima's first major setback as an author, and the book's disastrous reception came as a harsh psychological blow.[84][85]

Many of Mishima's most famous and highly regarded works were written prior to 1960. However, until that year he had not written works that were seen as especially political.[86] In the summer of 1960, Mishima became interested in the massive Anpo protests against an attempt by U.S.-backed Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi to revise the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security Between the United States and Japan (known as "Anpo" in Japanese) in order to cement the U.S.–Japan military alliance into place.[87] Although he did not directly participate in the protests, he often went out in the streets to observe the protestors in action and kept extensive newspaper clipping covering the protests.[86] In June 1960, at the climax of the protest movement, Mishima wrote a commentary in the Mainichi Shinbun newspaper, entitled "A Political Opinion".[88] In the critical essay, he argued that leftist groups such as the Zengakuren student federation, the Socialist Party, and the Communist Party were falsely wrapping themselves in the banner of "defending democracy" and using the protest movement to further their own ends. Mishima warned against the dangers of the Japanese people following ideologues who told lies with honeyed words. Although Mishima criticized Kishi as a "nihilist" who had subordinated himself to the United States, Mishima concluded that he would rather vote for a strong-willed realist "with neither dreams nor despair" than a mendacious but eloquent ideologue.[89]

Shortly after the Anpo Protests ended, Mishima began writing one of his most famous short stories, Patriotism (憂国, Yūkoku), glorifying the actions of a young right-wing ultranationalist Japanese army officer who commits suicide after a failed revolt against the government during the February 26 Incident.[88] The following year, he published the first two parts of his three-part play Tenth-Day Chrysanthemum (十日の菊, Tōka no kiku), which celebrates the actions of the 26 February revolutionaries.[88]

Mishima's newfound interest in contemporary politics shaped his novel After the Banquet (宴のあと Utage no ato), also published in 1960, which so closely followed the events surrounding politician Hachirō Arita's campaign to become governor of Tokyo that Mishima was sued for invasion of privacy.[90] The next year, Mishima published The Frolic of the Beasts (獣の戯れ Kemono no tawamure), a parody of the classical Noh play Motomezuka, written in the 14th-century playwright Kiyotsugu Kan'ami. In 1962, Mishima produced his most artistically avant-garde work Beautiful Star (美しい星 Utsukushii hoshi), which at times comes close to science fiction. Although the novel received mixed reviews from the literary world, prominent critic Takeo Okuno singled it out for praise as part of a new breed of novels that was overthrowing longstanding literary conventions in the tumultuous aftermath of the Anpo Protests. Alongside Kōbō Abe's Woman of the Dunes (砂の女, Suna no onna), published that same year, Okuno considered A Beautiful Star an "epoch-making work" which broke free of literary taboos and preexisting notions of what literature should be in order to explore the author's personal creativity.[91]

In 1965, Mishima wrote the play Madame de Sade (サド侯爵夫人 Sado kōshaku fujin) that explores the complex figure of the Marquis de Sade, traditionally upheld as an exemplar of vice, through a series of debates between six female characters, including the Marquis' wife, the Madame de Sade. At the end of the play, Mishima offers his own interpretation of what he considered to be one of the central mysteries of the de Sade story—the Madame de Sade's unstinting support for her husband while he was in prison and her sudden decision to renounce him upon his release.[92][93] Mishima's play was inspired in part by his friend Tatsuhiko Shibusawa's 1960 Japanese translation of the Marquis de Sade's novel Juliette and a 1964 biography Shibusawa wrote of de Sade.[94] Shibusawa's sexually explicit translation became the focus of a sensational obscenity trial remembered in Japan as the "Sade Case" (サド裁判, Sado saiban), which was ongoing as Mishima wrote the play.[92] In 1994, Madame de Sade was evaluated as the "greatest drama in the history of postwar theater" by Japanese theater criticism magazine Theater Arts.[95][96]

Mishima was considered for the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1963, 1964, and 1965,[97] and was a favorite of many foreign publications.[98] However, in 1968 his early mentor Kawabata won the Nobel Prize and Mishima realized that the chances of it being given to another Japanese author in the near future were slim.[99] In a work published in 1970, Mishima wrote that the writers he paid most attention to in modern western literature were Georges Bataille, Pierre Klossowski, and Witold Gombrowicz.[100]

Acting and modelling

Mishima was also an actor, and starred in Yasuzo Masumura's 1960 film, Afraid to Die (からっ風野郎 Karakkaze yarō), for which he also sang the theme song (lyrics by himself; music by Shichirō Fukazawa).[101][102] He performed in films like Patriotism or the Rite of Love and Death (憂国 Yūkoku, directed by himself, 1966), Black Lizard (黒蜥蜴 Kurotokage, directed by Kinji Fukasaku, 1968) and Hitokiri (人斬り, directed by Hideo Gosha, 1969).

Mishima was featured as the photo model in photographer Eikoh Hosoe's book Bara-kei (薔薇刑, Ba-ra-kei: Ordeal by Roses), as well as in Tamotsu Yatō's photobooks Young Samurai: Bodybuilders of Japan (体道~日本のボディビルダーたち Taidō: Nihon no bodybuilder tachi) and Otoko: Photo Studies of the Young Japanese Male (男 Otoko). American author Donald Richie gave an eyewitness account of seeing Mishima, dressed in a loincloth and armed with a sword, posing in the snow for one of Tamotsu Yatō's photoshoots.[103]

In the men's magazine Heibon Punch, to which Mishima had contributed various essays and criticisms, he won first place in the "Mr. Dandy" reader popularity poll in 1967 with 19,590 votes, beating second place Toshiro Mifune by 720 votes.[104] In the next reader popularity poll, "Mr. International", Mishima ranked second behind French President Charles de Gaulle.[104] At that time in the late 1960s, Mishima was the first celebrity to be described as a "superstar" (sūpāsutā) by the Japanese media.[105]

Private life

In 1955, Mishima took up weight training to overcome an inferiority complex about his weak constitution, and his strictly observed workout regimen of three sessions per week was not disrupted for the final 15 years of his life. In his 1968 essay Sun and Steel (太陽と鉄 Taiyō to tetsu),[106] Mishima deplored the emphasis given by intellectuals to the mind over the body. He later became very skilled (5th Dan) at kendo (traditional Japanese swordsmanship), and became 2nd Dan in battōjutsu, and 1st Dan in karate. In 1956, he tried boxing for a short period of time. In the same year, he developed an interest in UFOs and became a member of the Japan Flying Saucer Research Association (日本空飛ぶ円盤研究会 Nihon soratobu enban kenkyukai).[107] In 1954, he fell in love with Sadako Toyoda (豊田貞子), who became the model for main characters in The Sunken Waterfall (沈める滝 Shizumeru taki) and The Seven Bridges (橋づくし Hashi zukushi).[108][109] Mishima hoped to marry her, but they broke up in 1957.[58][110]

After briefly considering marriage with Michiko Shōda (正田美智子), who later married Crown Prince Akihito and became Empress Michiko,[111] Mishima married Yōko (瑤子, née Sugiyama), the daughter of Japanese-style painter Yasushi Sugiyama (杉山寧), on 1 June 1958. The couple had two children: a daughter named Noriko (紀子) (born 2 June 1959) and a son named Iichirō (威一郎) (born 2 May 1962).[112] Noriko eventually married the diplomat Koji Tomita (冨田浩司).[113]

While working on his novel Forbidden Colors (禁色 Kinjiki), Mishima visited gay bars in Japan.[114] Mishima's sexual orientation was an issue that bothered his wife, and she always denied his homosexuality after his death.[115] In 1998, the writer Jirō Fukushima (福島次郎) published an account of his relationship with Mishima in 1951, including fifteen letters (not love letters) from the famed novelist.[116] Mishima's children successfully sued Fukushima and the publisher for copyright violation over the use of Mishima's letters.[117][116][118] Publisher Bungeishunjū had argued that the contents of the letters were "practical correspondence" rather than copyrighted works. However, the ruling for the plaintiffs declared, "In addition to clerical content, these letters describe the Mishima's own feelings, his aspirations, and his views on life, in different words from those in his literary works."[119][lower-alpha 8]

In February 1961, Mishima became embroiled in the aftermath of the Shimanaka incident (嶋中事件 Shimanaka Jiken). In 1960, the author Shichirō Fukazawa (深沢七郎) had published the satirical short story The Tale of an Elegant Dream (風流夢譚 Fūryū Mutan) in the mainstream magazine Chūō Kōron. It contained a dream sequence (in which the Emperor and Empress are beheaded by a guillotine) that led to outrage from right-wing ultra-nationalist groups, and numerous death threats against Fukazawa, any writers believed to have been associated with him, and Chūō Kōron magazine itself.[122] On 1 February 1961, Kazutaka Komori (小森一孝), a seventeen-year-old rightist, broke into the home of Hōji Shimanaka (嶋中鵬二), the president of Chūō Kōron, killed his maid with a knife and severely wounded his wife.[123] In the aftermath, Fukazawa went into hiding, and dozens of writers and literary critics, including Mishima, were provided with round-the-clock police protection for several months;[124] Mishima was included because a rumor that Mishima had personally recommended "The Tale of an Elegant Dream" for publication became widespread, and even though he repeatedly denied the claim, he received hundreds of death threats.[124] In later years, Mishima harshly criticized Komori, arguing that those who harm women and children are neither patriots nor traditional right-wingers, and that an assassination attempt should be a one-on-one confrontation with the victim at the risk of the assassin's life. Mishima also argued that it was the custom of traditional Japanese patriots to immediately commit suicide after committing an assassination.[125]

In 1963, the Harp of Joy Incident occurred within the theatrical troupe Bungakuza (文学座), to which Mishima belonged. He wrote a play titled The Harp of Joy (喜びの琴 Yorokobi no koto), but star actress Haruko Sugimura (杉村春子) and other Communist Party-affiliated actors refused to perform because the protagonist held anti-communist views and mentioned criticism about a conspiracy of world communism in his lines. As a result of this ideological conflict, Mishima quit Bungakuza and later formed the troupe Neo Littérature Théâtre (劇団NLT, Gekidan NLT) with playwrights and actors who had quit Bungakuza along with him, including Seiichi Yashio (矢代静一), Takeo Matsuura (松浦竹夫), and Nobuo Nakamura (中村伸郎). When Neo Littérature Théâtre experienced a schism in 1968, Mishima formed another troupe, the Roman Theatre (浪曼劇場, Rōman Gekijō), and worked with Matsuura and Nakamura again.[126][127][128]

During the Tokyo Olympics in 1964, Mishima interviewed various athletes every day and wrote articles as a newspaper correspondent.[129][130] He had eagerly anticipated the long-awaited return of the Olympics to Japan after the 1940 Tokyo Olympics were cancelled due to Japan's war in China. Mishima expressed his excitement in his report on the opening ceremonies: "It can be said that ever since Lafcadio Hearn called the Japanese "the Greeks of the Orient," the Olympics were destined to be hosted by Japan someday."[131]

Mishima hated Ryokichi Minobe, who was a communist and the governor of Tokyo beginning in 1967.[132] Influential persons in the conservative Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), including Takeo Fukuda and Kiichi Aichi, had been Mishima's superiors during his time at the Ministry of the Treasury, and Prime Minister Eisaku Satō came to know Mishima because his wife, Hiroko, was a fan of Mishima's work. Based on these connections LDP officials solicited Mishima to run for the LDP as governor of Tokyo against Minobe, but Mishima had no intention of becoming a politician.[132]

Mishima was fond of manga and gekiga, especially the drawing style of Hiroshi Hirata (平田弘史), a mangaka best known for his samurai gekiga; the slapstick, absurdist comedy in Fujio Akatsuka's Mōretsu Atarō (もーれつア太郎), and the imaginativeness of Shigeru Mizuki's GeGeGe no Kitarō (ゲゲゲの鬼太郎).[133][134] Mishima especially loved reading the boxing manga Ashita no Joe (あしたのジョー, "Tomorrow's Joe") in Weekly Shōnen Magazine every week.[135][lower-alpha 9] Ultraman and Godzilla were his favorite kaiju fantasies, and he once compared himself to "Godzilla's egg" in 1955.[136][137] On the other hand, he disliked story manga with humanist or cosmopolitan themes, such as Osamu Tezuka's Phoenix (火の鳥, Hi no tori).[133][134]

Mishima was a fan of science fiction, contending that "science fiction will be the first literature to completely overcome modern humanism".[138] He praised Arthur C. Clarke's Childhood's End in particular. While acknowledging "inexpressible unpleasant and uncomfortable feelings after reading it," he declared, "I'm not afraid to call it a masterpiece."[139]

Mishima traveled to Shimoda on the Izu Peninsula with his wife and children every summer from 1964 onwards.[140][141] In Shimoda, Mishima often enjoyed eating local seafood with his friend Henry Scott-Stokes.[141] Mishima never showed any hostility towards the US in front of foreign friends like Scott-Stokes, until Mishima heard that the name of the inn where Scott-Stokes was staying was Kurofune (lit. black ship), at which point his voice suddenly became low and he said in a sullen manner, "Why? Why do you stay at a place with such a name?". Mishima liked ordinary American people after the war, and he and his wife had even visited Disneyland as newlyweds.[lower-alpha 10] However, he clearly retained a strong sense of hostility toward the "black ships" of Commodore Matthew C. Perry, who forcibly opened Japan up to unequal international relations at the end of the Edo period, and had destroyed the peace of Edo, where vivid chōnin culture was flourishing.[141]

Harmony of Pen and Sword

Mishima's nationalism grew towards the end of his life. In 1966, he published his short story The Voices of the Heroic Dead (英霊の聲 Eirei no koe), in which he denounced Emperor Hirohito for renouncing his own divinity after World War II. He argued that the soldiers who had died in the February 26 Incident (二・二六事件 Ni-Ni-Roku Jiken) and the Japanese Special Attack Units (特攻隊, Tokkōtai) had died for their "living god" Emperor, and that Hirohito's renunciation of his own divinity meant that all those deaths had been in vain. Mishima said that His Majesty had become a human when he should be a God.[143][144]

In February 1967, Mishima joined fellow authors Yasunari Kawabata, Kōbō Abe, and Jun Ishikawa in issuing a statement condemning China's Cultural Revolution for suppressing academic and artistic freedom.[145][146] However, only one Japanese newspaper carried the full text of their statement.[147]

In September 1967 Mishima and his wife visited India at the invitation of the Indian government. He traveled widely and met with Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and President Zakir Hussain.[148] He left extremely impressed by Indian culture, and what he felt was the Indian people's determination to resist Westernization and protect traditional ways.[149] Mishima feared that his fellow Japanese were too enamored of modernization and western-style materialism to protect traditional Japanese culture.[148] While in New Delhi, he spoke at length with an unnamed colonel in the Indian Army who had experienced skirmishes with Chinese troops on the Sino-Indian border. The colonel warned Mishima of the strength and fighting spirit of the Chinese troops. Mishima later spoke of his sense of danger regarding what he perceived to be a lack of concern in Japan about the need to bolster Japan's national defense against the threat from Communist China.[150][151][lower-alpha 11] On his way home from India, Mishima also stopped in Thailand and Laos; his experiences in the three nations became the basis for portions of his novel The Temple of Dawn (暁の寺, Akatsuki no tera), the third in his tetralogy The Sea of Fertility (豊饒の海 Hōjō no Umi).[153]

In 1968, Mishima wrote a play titled My Friend Hitler (わが友ヒットラー Waga tomo Hittorā), in which he depicted the historical figures of Adolf Hitler, Gustav Krupp, Gregor Strasser, and Ernst Röhm as mouthpieces to express his own views on fascism and beauty.[86] Mishima explained that after writing the all-female play Madame de Sade, he wanted to write a counterpart play with an all-male cast.[154] Mishima wrote of My Friend Hitler, "You may read this tragedy as an allegory of the relationship between Ōkubo Toshimichi and Saigō Takamori" (two heroes of Japan's Meiji Restoration who initially worked together but later had a falling out).[155]

That same year, he wrote Life for Sale (命売ります, Inochi Urimasu), a humorous story about a man who, after failing to commit suicide, advertises his life for sale.[156] In a review of the English translation, novelist Ian Thomson called it a "pulp noir" and a "sexy, camp delight," but also noted that, "beneath the hard-boiled dialogue and the gangster high jinks is a familiar indictment of consumerist Japan and a romantic yearning for the past."[157]

Mishima was hated by leftists who said Hirohito should have abdicated to take responsibility for the loss of life in the war. They also hated him for his outspoken commitment to bushido, the code of the samurai in The way of the samurai (葉隠入門 Hagakure Nyūmon), his support for the abolition of Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution, and for his contention in his critique The Defense of Culture (文化防衛論 Bunka Bōeiron) that preached the importance of the Emperor in Japanese cultures. Mishima regarded the postwar era of Japan, where no poetic culture and supreme artist was born, as an era of fake prosperity, and stated in The Defense of Culture:

In the postwar prosperity called Shōwa Genroku, where there are no Chikamatsu Monzaemon, Ihara Saikaku, Matsuo Bashō, only infestation of flashy manners and customs in there. Passion is dried up, strong realism dispels the ground, and the deepening of poetry is neglected. That is, there are no Chikamatsu, Saikaku, or Basho now.[158]

In other critical essays,[lower-alpha 12] Mishima argued that the national spirit which cultivated in Japan's long history is the key to national defense, and he had apprehensions about the insidious "indirect aggression" of the Chinese Communist Party, North Korea, and the Soviet Union.[13][14] In critical essays in 1969, Mishima explained Japan's difficult and delicate position and peculiarities between China, the Soviet Union, and the United States.

To put it simply, support for the Security Treaty means agreeing with the United States, and to oppose it means agreeing with the Soviet Union or the Chinese Communist Party, so after all, it's only just a matter of which foreign country to rely on, and therein the question of "what is Japan" is completely lacking. If you ask the Japanese, "Hey you, do you choose America, Soviet Union, or Chinese Communist Party?", if he is a true Japanese, he will withhold his attitude.[159][160]

In regards to those who strongly opposed the US military base in Okinawa and the Security Treaty:

They may appear to be nationalists and right-wingers in the foreign common sense, but in Japan, most of them are in fact left-wingers and communists.[161][160]

Throughout this period, Mishima continued to work on his magnum opus, The Sea of Fertility tetralogy of novels, which began appearing in a monthly serialized format in September 1965.[162] The four completed novels were Spring Snow (1969), Runaway Horses (1969), The Temple of Dawn (1970), and The Decay of the Angel (published posthumously in 1971). Mishima aimed for a very long novel with a completely different raison d'être from Western chronicle novels of the 19th and 20th centuries; rather than telling the story of a single individual or family, Mishima boldly set his goal as interpreting the entire human world.[163] In The Decay of the Angel, four stories convey the transmigration of the human soul as the main character goes through a series of reincarnations.[163] Mishima hoped to express in literary terms something akin to pantheism.[164] Novelist Paul Theroux blurbed the first edition of the English translation of The Sea of Fertility as "the most complete vision we have of Japan in the twentieth century" and critic Charles Solomon wrote in 1990 that "the four novels remain one of the outstanding works of 20th-Century literature and a summary of the author's life and work".[165]

Coup attempt and ritual suicide

In August 1966, Mishima visited Ōmiwa Shrine in Nara Prefecture, thought to be one of the oldest Shintō shrines in Japan, as well as the hometown of his mentor Zenmei Hasuda and the areas associated with the Shinpūren Rebellion (神風連の乱 Shinpūren no ran), an uprising against the Meiji government by samurai in 1876. This trip would become the inspiration for portions of Runaway Horses (奔馬 Honba), the second novel in the Sea of Fertility tetralogy. While in Kumamoto, Mishima purchased a Japanese sword for 100,000 yen. Mishima envisioned the reincarnation of Kiyoaki, the protagonist of the first novel Spring Snow, as a man named Isao who put his life on the line to bring about a restoration of direct rule by the Emperor against the backdrop of the League of Blood Incident (血盟団事件 Ketsumeidan jiken) in 1932.

From 12 April to 27 May 1967, Mishima underwent basic training with the Ground Self-Defense Force (GSDF).[166] Mishima had originally lobbied to train with the GSDF for six months, but was met with resistance from the Defense Agency.[166] Mishima's training period was finalized to 46 days, which required using some of his connections.[166] His participation in GSDF training was kept secret, both because the Defense Agency did not want to give the impression that anyone was receiving special treatment, and because Mishima wanted to experience "real" military life.[166][167] As such, Mishima trained under his birth name, Kimitake Hiraoka, and most of his fellow soldiers did not recognize him.[166]

From June 1967, Mishima became a leading figure in a plan to create a 10,000-man "Japan National Guard" (祖国防衛隊 Sokoku Bōeitai) as a civilian complement to Japan's Self Defense Forces. He began leading groups of right-wing college students to undergo basic training with the GDSF in the hope of training 100 officers to lead the National Guard.[168][169][167]

Like many other right-wingers, Mishima was especially alarmed by the riots and revolutionary actions undertaken by radical "New Left" university students, who took over dozens of college campuses in Japan in 1968 and 1969. On 26 February 1968, the 32nd anniversary of the February 26 Incident, he and several other right-wingers met at the editorial offices of the recently founded right-wing magazine Controversy Journal (論争ジャーナル Ronsō jaanaru), where they pricked their little fingers and signed a blood oath promising to die if necessary to prevent a left-wing revolution from occurring in Japan.[170][171] Mishima showed his sincerity by signing his birth name, Kimitake Hiraoka, in his own blood.[170][171]

When Mishima found that his plan for a large-scale Japan National Guard with broad public and private support failed to catch on,[172] he formed the Tatenokai (楯の会, "Shield Society") on 5 October 1968, a private militia composed primarily of right-wing college students who swore to protect the Emperor of Japan. The activities of the Tatenokai primarily focused on martial training and physical fitness, including traditional kendo sword-fighting and long-distance running.[173][174] Mishima personally oversaw this training himself. Initial membership was around 50, and was drawn primarily from students from Waseda University and individuals affiliated with Controversy Journal. The number of Tatenokai members later increased to 100.[175][168] Some of the members had graduated from university and were employed, while some were already working adults when they enlisted.[176]

On 25 November 1970, Mishima and four members of the Tatenokai—Masakatsu Morita (森田必勝), Masahiro Ogawa (小川正洋), Masayoshi Koga (小賀正義), and Hiroyasu Koga (古賀浩靖)—used a pretext to visit the commandant Kanetoshi Mashita (益田兼利) of Camp Ichigaya, a military base in central Tokyo and the headquarters of the Eastern Command of the Japan Self-Defense Forces.[115] Inside, they barricaded the office and tied the commandant to his chair. Mishima wore a white hachimaki headband with a red hinomaru circle in the center bearing the kanji for "To be reborn seven times to serve the country" (七生報國, Shichishō hōkoku), which was a reference to the last words of Kusunoki Masasue, the younger brother of the 14th century imperial loyalist samurai Kusunoki Masashige (楠木正成), as the two brothers died fighting to defend the Emperor.[177] With a prepared manifesto and a banner listing their demands, Mishima stepped out onto the balcony to address the soldiers gathered below. His speech was intended to inspire a coup d'état to restore the power of the emperor. He succeeded only in irritating the soldiers, and was heckled, with jeers and the noise of helicopters drowning out some parts of his speech. In his speech Mishima rebuked the JSDF for their passive acceptance of a constitution that "denies (their) own existence" and shouted to rouse them, "Where has the spirit of the samurai gone?" In his final written appeal that Morita and Ogawa scattered copies of from the balcony, Mishima expressed his dissatisfaction with the half-baked nature of the JSDF:

It is self-evident that the United States would not be pleased with a true Japanese volunteer army protecting the land of Japan.[178][179]

After he finished reading his prepared speech in a few minutes' time, Mishima cried out "Long live the Emperor!" (天皇陛下万歳 Tenno-heika banzai) three times. He then retreated into the commandant's office and apologized to the commandant, saying,

"We did it to return the JSDF to the Emperor. I had no choice but to do this."[180][181][182]

Mishima then committed seppuku, a form of ritual suicide by disembowelment associated with the samurai. Morita had been assigned to serve as Mishima's second (kaishakunin), cutting off his head with a sword at the end of the ritual to spare him unnecessary pain. However, Morita proved unable to complete his task, and after three failed attempts to sever Mishima's head, Koga had to step in and complete the task.[180][181][182]

According to the testimony of the surviving coup members, originally all four Tatenokai members had planned to commit seppuku along with Mishima. However Mishima attempted to dissuade them and three of the members acquiesced to his wishes. Only Morita persisted, saying, "I can't let Mr. Mishima die alone." But Mishima knew that Morita had a girlfriend and still hoped he might live. Just before his seppuku, Mishima tried one more time to dissuade him, saying "Morita, you must live, not die."[183][184][lower-alpha 13] Nevertheless, after Mishima's seppuku, Morita knelt and stabbed himself in the abdomen and Koga acted as kaishakunin again.[185]

This coup attempt is called The Mishima Incident (三島事件 Mishima jiken) in Japan.[lower-alpha 14]

Another traditional element of the suicide ritual was the composition of so-called death poems by the Tatenokai members before their entry into the headquarters.[187] Having been enlisted in the Ground Self-Defense Force for about four years, Mishima and other Tatenokai members, alongside several officials, were secretly researching coup plans for a constitutional amendment. They thought there was a chance when security dispatch (治安出動 Chian Shutsudo) was dispatched to subjugate the Zenkyoto revolt. However, Zenkyoto was suppressed easily by the Riot Police Unit in October 1969. These officials gave up the coup of constitutional amendment, and Mishima was disappointed in them and the actual circumstances in Japan after World War II.[188] Officer Kiyokatsu Yamamoto (山本舜勝), Mishima's training teacher, explained further:

The officers had a trusty connection with the U.S.A.F. (includes U.S.F.J), and with the approval of the U.S. army side, they were supposed to carry out a security dispatch toward the Armed Forces of the Japan Self-Defense Forces. However, due to the policy change (reversal) of U.S. by Henry Kissinger who prepared for visiting China in secret (changing relations between U.S. and China), it became a situation where the Japanese military was not allowed legally.[188]

Mishima planned his suicide meticulously for at least a year and no one outside the group of hand-picked Tatenokai members knew what he was planning.[189][190] His biographer, translator John Nathan, suggests that the coup attempt was only a pretext for the ritual suicide of which Mishima had long dreamed.[191] His friend Scott-Stokes, another biographer, says that "Mishima is the most important person in postwar Japan", and described the shackles of the constitution of Japan:

Mishima cautioned against the lack of reality in the basic political controversy in Japan and the particularity of Japan's democratic principles.[192]

Scott-Stokes noted a meeting with Mishima in his diary entry for 3 September 1970, at which Mishima, with a dark expression on his face, said:

Japan lost its spiritual tradition, and materialism infested instead. Japan is under the curse of a Green Snake now. The Green Snake bites on Japanese chest. There is no way to escape this curse.[193]

Scott-Stokes told Takao Tokuoka in 1990 that he took the Green Snake to mean the U.S. dollar.[194] Between 1968 and 1970, Mishima also said words about Japan's future. Mishima's senior friend and father heard from Mishima:

Japan will be hit hard. One day, the United States suddenly contacts China over Japan's head, Japan will only be able to look up from the bottom of the valley and eavesdrop on the conversation slightly. Our friend Taiwan will say that "it will no longer be able to count on Japan", and Taiwan will go somewhere. Japan may become an orphan in the Orient, and may eventually fall into the product of slave dealers.[195]

Mishima's corpse was returned home the day after his death. His father Azusa had been afraid to see his son whose appearance had completely changed. However, when he looked into the casket fearfully, Mishima's head and body had been sutured neatly, and his dead face, to which makeup had been beautifully applied, looked as if he were alive due to the police officers. They said: "We applied funeral makeup carefully with special feelings, because it is the body of Dr. Mishima, whom we have always respected secretly."[196] Mishima's body was dressed in the Tatenokai uniform, and the guntō was firmly clasped at the chest according to the will that Mishima entrusted to his friend Kinemaro Izawa (伊沢甲子麿).[196][197] Azusa put the manuscript papers and fountain pen that his son cherished in the casket together.[196][lower-alpha 15] Mishima had made sure his affairs were in order and left money for the legal defence of the three surviving Tatenokai members—Masahiro Ogawa (小川正洋), Masayoshi Koga (小賀正義), and Hiroyasu Koga.[190][lower-alpha 16] After the incident, there were exaggerated media commentaries that "it was a fear of the revival of militarism".[194][201] The commandant who was made a hostage said in the trial,

I didn't feel hate towards the defendants at that time. Thinking about the country of Japan, thinking about the JSDF, the pure hearts of thinking about our country that did that kind of thing, I want to buy it as an individual.[180]

The day of the Mishima Incident (25 November) was the date when Hirohito (Emperor Shōwa) became regent and the Emperor Shōwa made the Humanity Declaration at the age of 45. Researchers believe that Mishima chose that day to revive the "God" by dying as a scapegoat, at the same age as when the Emperor became a human.[202][203] There are also views that the day corresponds to the date of execution (after the adoption of the Gregorian calendar) of Yoshida Shōin (吉田松陰), whom Mishima respected,[196] or that Mishima had set his period of bardo (中有 Chuu) for reincarnation because the 49th day after his death was his birthday, 14 January.[204] On his birthday, Mishima's remains were buried in the grave of the Hiraoka Family at Tama Cemetery.[196] In addition, 25 November is the day he began writing Confessions of a Mask (仮面の告白, Kamen no kokuhaku), and this work was announced as "Techniques of Life Recovery", "Suicide inside out". Mishima also wrote down in notes for this work,

This book is a will for leave in the Realm of Death where I used to live. If you take a movie of a suicide jumped, and rotate the film in reverse, the suicide person jumps up from the valley bottom to the top of the cliff at a furious speed and he revives.[205][206]

Writer Takashi Inoue believes he wrote Confessions of a Mask to live in postwar Japan, and to get away from his "Realm of Death"; by dying on the same date that he began to write Confessions of a Mask, Mishima intended to dismantle all of his postwar creative activities and return to the "Realm of Death" where he used to live.[206]

Legacy

Much speculation has surrounded Mishima's suicide. At the time of his death he had just completed the final book in his Sea of Fertility tetralogy.[115] He was recognized as one of the most important post-war stylists of the Japanese language. Mishima wrote 34 novels, about 50 plays, about 25 books of short stories, at least 35 books of essays, one libretto, and one film.[207]

Mishima's grave is located at the Tama Cemetery in Fuchū, Tokyo. The Mishima Prize was established in 1988 to honor his life and works. On 3 July 1999, "Yukio Mishima Literary Museum" (三島由紀夫文学館, Mishima Yukio Bungaku-kan) was opened in Yamanakako, Yamanashi Prefecture.[208]

The Mishima Incident helped inspire the formation of New Right (新右翼, shin uyoku) groups in Japan, such as the "Issuikai" (一水会), founded by Tsutomu Abe (阿部勉), who was Mishima's follower. Compared to older groups such as Bin Akao's Greater Japan Patriotic Party that took a pro-American, anti-communist stance, New Right groups such as the Issuikai tended to emphasize ethnic nationalism and anti-Americanism.[209]

A memorial service deathday for Mishima, called "Patriotism Memorial" (憂国忌 Yūkoku-ki), is held every year in Japan on 25 November by the "Yukio Mishima Study Group" (三島由紀夫研究会 Mishima Yukio Kenkyūkai) and former members of the "Japan Student Alliance" (日本学生同盟 Nihon Gakusei Dōmei).[210] Apart from this, a memorial service is held every year by former Tatenokai members, which began in 1975, the year after Masahiro Ogawa, Masayoshi Koga, and Hiroyasu Koga were released on parole.[211]

A variety of cenotaphs and memorial stones have been erected in honor of Mishima's memory in various places around Japan. For example, stones have been erected at Hachiman Shrine in Kakogawa City, Hyogo Prefecture, where his grandfather's permanent domicile was;[212] in front of the 2nd company corps at JGSDF Camp Takigahara;[213] and in one of Mishima's acquaintance's home garden.[214] There is also a "Monument of Honor Yukio Mishima & Masakatsu Morita" in front of the Rissho University Shonan High school in Shimane Prefecture.[215]

The Mishima Yukio Shrine was built in the suburb of Fujinomiya, Shizuoka Prefecture, on 9 January 1983.[216][217]

A 1985 biographical film by Paul Schrader titled Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters depicts his life and work; however, it has never been given a theatrical presentation in Japan. A 2012 Japanese film titled 11:25 The Day He Chose His Own Fate also looks at Mishima's last day. The 1983 gay pornographic film Beautiful Mystery satirised the homosexual undertones of Mishima's career.[218][219]

In 2014, Mishima was one of the inaugural honourees in the Rainbow Honor Walk, a walk of fame in San Francisco's Castro neighbourhood noting LGBTQ people who have "made significant contributions in their fields".[220][221][222]

David Bowie painted a large expressionist portrait of Mishima, which he hung at his Berlin residence.[223]

Awards

- Shincho Prize from Shinchosha Publishing, 1954, for The Sound of Waves

- Kishida Prize for Drama from Shinchosha Publishing, 1955 for Termites' Nest (白蟻の巣 Shiroari no Su)

- Yomiuri Prize from Yomiuri Newspaper Co., for best novel, 1956, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion[224]

- Shuukan Yomiuri Prize for Shingeki from Yomiuri Newspaper Co., 1958, for Rose and Pirate (薔薇と海賊 Bara to Kaizoku)

- Yomiuri Prize from Yomiuri Newspaper Co., for best drama, 1961, The Chrysanthemum on the Tenth (The Day After the Fair) (十日の菊 Tōka no kiku)

- One of six finalists for the Nobel Prize in Literature, 1963.[225]

- Mainichi Art Prize from Mainichi Shimbun, 1964, for Silk and Insight

- Art Festival Prize from the Ministry of Education, 1965, for Madame de Sade

Major works

Literature

| Japanese title | English title | Year (first appeared) | English translator | Year (English translation) | ISBN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 花ざかりの森 Hanazakari no Mori (short story) |

"Forest in Full Bloom" | 1941 | Andrew Rankin | 2000 | |

| サーカス Sākasu (short story) |

"The Circus" | 1948 | Andrew Rankin | 1999[226] | |

| 盗賊 Tōzoku |

Thieves | 1947–1948 | |||

| 假面の告白 (仮面の告白) Kamen no Kokuhaku |

Confessions of a Mask | 1949 | Meredith Weatherby | 1958 | ISBN:0-8112-0118-X |

| 愛の渇き Ai no Kawaki |

Thirst for Love | 1950 | Alfred H. Marks | 1969 | ISBN:4-10-105003-1 |

| 純白の夜 Junpaku no Yoru |

Pure White Nights | 1950 | |||

| 青の時代 Ao no Jidai |

The Age of Blue | 1950 | |||

| 禁色 Kinjiki |

Forbidden Colors | 1951–1953 | Alfred H. Marks | 1968–1974 | ISBN:0-375-70516-3 |

| 真夏の死 Manatsu no shi (short story) |

Death in Midsummer | 1952 | Edward G. Seidensticker | 1956 | |

| 潮騒 Shiosai |

The Sound of Waves | 1954 | Meredith Weatherby | 1956 | ISBN:0-679-75268-4 |

| 詩を書く少年 Shi o Kaku Shōnen (short story) |

"The Boy Who Wrote Poetry" | 1954 | Ian H. Levy | 1977[226] | |

| 沈める滝 Shizumeru Taki |

The Sunken Waterfall | 1955 | |||

| 金閣寺 Kinkaku-ji |

The Temple of the Golden Pavilion | 1956 | Ivan Morris | 1959 | ISBN:0-679-75270-6 |

| 鹿鳴館 Rokumeikan (play) |

Rokumeikan | 1956 | Hiroaki Sato | 2002 | ISBN:0-231-12633-6 |

| 鏡子の家 Kyōko no Ie |

Kyoko's House | 1959 | |||

| 宴のあと Utage no Ato |

After the Banquet | 1960 | Donald Keene | 1963 | ISBN:0-399-50486-9 |

| スタア "Sutā" (novella) |

Star (novella) | 1960[227] | Sam Bett | 2019 | ISBN:978-0-8112-2842-8 |

| 憂國(憂国) Yūkoku (short story) |

"Patriotism" | 1961 | Geoffrey W. Sargent | 1966 | ISBN:0-8112-1312-9 |

| 黒蜥蜴 Kuro Tokage (play) |

The Black Lizard | 1961 | Mark Oshima | 2007 | ISBN:1-929280-43-2 |

| 獣の戯れ Kemono no Tawamure |

The Frolic of the Beasts | 1961 | Andrew Clare | 2018 | ISBN:978-0-525-43415-3 |

| 美しい星 Utsukushii Hoshi |

Beautiful Star | 1962 | Stephen Dodd | 2022[228][229] | ISBN:978-0-241-54556-0 (paperback) ISBN:978-0-141-99258-7 (ebook) |

| 肉体の学校 Nikutai no Gakkō |

The School of Flesh | 1963 | |||

| 午後の曳航 Gogo no Eikō |

The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea | 1963 | John Nathan | 1965 | ISBN:0-679-75015-0 |

| 絹と明察 Kinu to Meisatsu |

Silk and Insight | 1964 | Hiroaki Sato | 1998 | ISBN:0-7656-0299-7 |

| 三熊野詣 Mikumano Mōde (short story) |

"Acts of Worship" | 1965 | John Bester | 1995 | ISBN:0-87011-824-2 |

| 孔雀 Kujaku (short story) |

"The Peacocks" | 1965 | Andrew Rankin | 1999 | ISBN:1-86092-029-2 |

| サド侯爵夫人 Sado Kōshaku Fujin (play) |

Madame de Sade | 1965 | Donald Keene | 1967 | ISBN:1-86092-029-2 |

| 英霊の聲 Eirei no Koe (short story) |

"The Voices of the Heroic Dead" | 1966 | |||

| 朱雀家の滅亡 Suzaku-ke no Metsubō (play) |

The Decline and Fall of The Suzaku | 1967 | Hiroaki Sato | 2002 | ISBN:0-231-12633-6 |

| 命売ります Inochi Urimasu |

Life for Sale | 1968 | Stephen Dodd | 2019 | ISBN:978-0-241-33314-3 |

| わが友ヒットラー Waga Tomo Hittorā (play) |

My Friend Hitler and Other Plays | 1968 | Hiroaki Sato | 2002 | ISBN:0-231-12633-6 |

| 癩王のテラス Raiō no Terasu (play) |

The Terrace of The Leper King | 1969 | Hiroaki Sato | 2002 | ISBN:0-231-12633-6 |

| 豐饒の海 (豊饒の海) Hōjō no Umi |

The Sea of Fertility tetralogy: | 1965–1971 | ISBN:0-677-14960-3 | ||

| I. 春の雪 Haru no Yuki |

1. Spring Snow | 1965–1967 | Michael Gallagher | 1972 | ISBN:0-394-44239-3 |

| II. 奔馬 Honba |

2. Runaway Horses | 1967–1968 | Michael Gallagher | 1973 | ISBN:0-394-46618-7 |

| III. 曉の寺 Akatsuki no Tera |

3. The Temple of Dawn | 1968–1970 | E. Dale Saunders and Cecilia S. Seigle | 1973 | ISBN:0-394-46614-4 |

| IV. 天人五衰 Tennin Gosui |

4. The Decay of the Angel | 1970–1971 | Edward Seidensticker | 1974 | ISBN:0-394-46613-6 |

Critical essay

| Japanese title | English title | Year (first appeared) | English translation, year | ISBN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| アポロの杯 Aporo no Sakazuki |

The Cup of Apollo | 1952 | ||

| 不道徳教育講座 Fudōtoku Kyōiku Kōza |

Lectures on Immoral Education | 1958–1959 | ||

| 私の遍歴時代 Watashi no Henreki Jidai |

My Wandering Period | 1963 | ||

| 太陽と鐡 (太陽と鉄) Taiyō to Tetsu |

Sun and Steel | 1965–1968 | John Bester | ISBN:4-7700-2903-9 |

| 葉隠入門 Hagakure Nyūmon |

Way of the Samurai | 1967 | Kathryn Sparling, 1977 | ISBN:0-465-09089-3 |

| 文化防衛論 Bunka Bōei-ron |

The Defense of the Culture | 1968 | ||

| 革命哲学としての陽明学 Kakumei tetsugaku toshiteno Yomegaku |

Wang Yangming Thought as Revolutionary Philosophy | 1970 | Harris I. Martin, 1971[226] |

Plays for classical Japanese theatre

In addition to contemporary-style plays such as Madame de Sade, Mishima wrote for two of the three genres of classical Japanese theatre: Noh and Kabuki (as a proud Tokyoite, he would not even attend the Bunraku puppet theatre, always associated with Osaka and the provinces).[230]

Though Mishima took themes, titles and characters from the Noh canon, his twists and modern settings, such as hospitals and ballrooms, startled audiences accustomed to the long-settled originals.

Donald Keene translated Kindai Nogaku-shū (近代能楽集, Five Modern Noh Plays) (Tuttle, 1981; ISBN:0-8048-1380-9). Most others remain untranslated and so lack an "official" English title; in such cases it is therefore preferable to use the rōmaji title.

| Year (first appeared) | Japanese title | English title | Genre |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 邯鄲 Kantan |

The Magic Pillow | Noh |

| 1951 | 綾の鼓 Aya no Tsuzumi |

The Damask Drum | Noh |

| 1952 | 卒塔婆小町 Sotoba Komachi |

Komachi at the Gravepost | Noh |

| 1954 | 葵の上 Aoi no Ue |

The Lady Aoi | Noh |

| 1954 | 鰯賣戀曳網 (鰯売恋曳網) Iwashi Uri Koi Hikiami |

The Sardine Seller's Net of Love | Kabuki |

| 1955 | 班女 Hanjo |

The Waiting Lady with the Fan | Noh |

| 1955 | 芙蓉露大内実記 Fuyō no Tsuyu Ōuchi Jikki |

The Blush on the White Hibiscus Blossom: Lady Fuyo and the True Account of the Ōuchi Clan | Kabuki |

| 1957 | 道成寺 Dōjōji |

Dōjōji Temple | Noh |

| 1959 | 熊野 Yuya |

Yuya | Noh |

| 1960 | 弱法師 Yoroboshi |

The Blind Young Man | Noh |

| 1969 | 椿説弓張月 Chinsetsu Yumiharizuki |

A Wonder Tale: The Moonbow or Half Moon (like a Bow and arrow setting up): The Adventures of Tametomo |

Kabuki |

Films

Mishima starred in multiple films. Patriotism was written and funded by himself, and he directed it in close cooperation with Masaki Domoto. Mishima also wrote a detailed account of the whole process, in which the particulars regarding costume, shooting expenses and the film's reception are delved into. Patriotism won the second prize at the Tours International Short Film Festival in January 1966.[231][232]

| Year | Title | United States release title(s) | Character | Director |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 純白の夜 Jumpaku no Yoru |

Unreleased in the U.S. | an extra (dance party scene) | Hideo Ōba |

| 1959 | 不道徳教育講座 Fudōtoku Kyōikukōza |

Unreleased in the U.S. | himself as navigator | Katsumi Nishikawa |

| 1960 | からっ風野郎 Karakkaze Yarō |

Afraid to Die | Takeo Asahina (main character) |

Yasuzo Masumura |

| 1966 | 憂国 Yūkoku |

The Rite of Love and Death Patriotism |

Shinji Takeyama (main character) |

Yukio Mishima, Domoto Masaki (sub) |

| 1968 | 黒蜥蜴 Kurotokage |

Black Lizard | Human Statue | Kinji Fukasaku |

| 1969 | 人斬り Hitokiri |

Tenchu! | Tanaka Shinbei | Hideo Gosha |

Works about Mishima

- Collection of Photographs

- Ba-ra-kei: Ordeal by Roses (薔薇刑) by Eikō Hosoe and Mishima (photoerotic collection of images of Mishima, with his own commentary, 1963) (Aperture 2002 ISBN:0-89381-169-6)[233][234]

- Grafica: Yukio Mishima (Grafica Mishima Yukio (グラフィカ三島由紀夫)) by Kōichi Saitō, Kishin Shinoyama, Takeyoshi Tanuma, Ken Domon, Masahisa Fukase, Eikō Hosoe, Ryūji Miyamoto etc. (photoerotic collection of Yukio Mishima) (Shinchosha 1990 ISBN:978-4-10-310202-1)[235]

- Yukio Mishima's house (Mishima Yukio no Ie (三島由紀夫の家)) by Kishin Shinoyama (Bijutsu Shuppansha 1995 ISBN:978-4-568-12055-4)[236]

- The Death of a Man (Otoko no shi (男の死)) by Kishin Shinoyama and Mishima (photo collection of death images of Japanese men including a sailor, a construction worker, a fisherman, and a soldier, those were Mishima did modeling in 1970) (Rizzoli 2020 ISBN:978-0-8478-6869-8)[237]

- Book

- Reflections on the Death Of Mishima by Henry Miller (1972, ISBN:0-912264-38-1) [238]

- The Day He Himself Shall Wipe My Tears Away (Mizukara waga namida wo nuguitamau hi (みずから我が涙をぬぐいたまう日)) by Kenzaburō Ōe (Kodansha, 1972, NCID BN04777478) – In addition to this, Kenzaburō Ōe wrote several works that mention the Mishima incident and Mishima a little.[239]

- Mishima: A Biography by John Nathan (Boston, Little, Brown and Company 1974, ISBN:0-316-59844-5)[240][241]

- The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima, by Henry Scott-Stokes (London : Owen, 1975 ISBN:0-7206-0123-1)[241][242]

- La mort volontaire au Japon, by Maurice Pinguet (Gallimard, 1984 ISBN:2070701891)[243][244]

- Der Magnolienkaiser: Nachdenken über Yukio Mishima by Hans Eppendorfer (1984, ISBN:3924040087)[245]

- Teito Monogatari (vol. 5–10) by Hiroshi Aramata (a historical fantasy novel. Mishima appears in series No.5, and he reincarnates a woman Michiyo Ohsawa in series No.6), (Kadokawa Shoten 1985 ISBN:4-04-169005-6)[246][247]

- Yukio Mishima by Peter Wolfe ("reviews Mishima's life and times, discusses, his major works, and looks at important themes in his novels," 1989, ISBN:0-8264-0443-X)[248]

- Escape from the Wasteland: Romanticism and Realism in the Fiction of Mishima Yukio and Oe Kenzaburo (Harvard-Yenching Institute Monograph Series, No 33) by Susan J. Napier (Harvard University Press, 1991 ISBN:0-674-26180-1)[249]

- Deadly Dialectics: Sex, Violence, and Nihilism in the World of Yukio Mishima by Roy Starrs (University of Hawaii Press, 1994, ISBN:0-8248-1630-7 and ISBN:0-8248-1630-7)[250]

- Rogue Messiahs: Tales of Self-Proclaimed Saviors by Colin Wilson (Mishima profiled in context of phenomenon of various "outsider" Messiah types), (Hampton Roads Publishing Company 2000 ISBN:1-57174-175-5)

- Mishima ou la vision du vide (Mishima : A Vision of the Void), essay by Marguerite Yourcenar trans. by Alberto Manguel 2001 ISBN:0-226-96532-5)[251][252]

- Yukio Mishima, Terror and Postmodern Japan by Richard Appignanesi (2002, ISBN:1-84046-371-6)

- Yukio Mishima's Report to the Emperor by Richard Appignanesi (2003, ISBN:978-0-9540476-6-5)

- The Madness and Perversion of Yukio Mishima by Jerry S. Piven. (Westport, Connecticut, Praeger Publishers, 2004 ISBN:0-275-97985-7)[253]

- Mishima's Sword – Travels in Search of a Samurai Legend by Christopher Ross (2006, ISBN:0-00-713508-4)[254]

- Mishima Reincarnation (Mishima tensei (三島転生)) by Akitomo Ozawa (小沢章友) (Popurasha, 2007, ISBN:978-4-591-09590-4) – A story in which the spirit of Mishima, who died at the Ichigaya chutonchi, floating and looks back on his life.[255]

- Biografia Ilustrada de Mishima by Mario Bellatin (Argentina, Editorian Entropia, 2009, ISBN:978-987-24797-6-3)

- Impossible (Fukano (不可能)) by Hisaki Matsuura (Kodansha, 2011, ISBN:978-4-06-217028-4) – A novel that assumed that Mishima has been survived the Mishima Incident.[256]

- Persona: A Biography of Yukio Mishima by Naoki Inose with Hiroaki Sato (Berkeley, California, Stone Bridge Press, 2012, ISBN:978-1-61172-008-2)[257]

- Yukio Mishima (Critical Lives) by Damian Flanagan (Reaktion Books, 2014, ISBN:978-1-78023-345-1)[258]

- Portrait of the Author as a Historian by Alexander Lee – an analysis of the central political and social threads in Mishima's novels (pages 54–55 "History Today" April 2017)

- Mishima, Aesthetic Terrorist: An Intellectual Portrait by Andrew Rankin (University of Hawaii Press, 2018, ISBN:0-8248-7374-2)[259]

- Film, TV

- Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985), a film directed by Paul Schrader[260]

- The Strange Case of Yukio Mishima (1985) BBC documentary directed by Michael Macintyre

- Yukio Mishima: Samurai Writer, a BBC documentary on Yukio Mishima, directed by Michael Macintyre, (1985, VHS ISBN:978-1-4213-6981-5, DVD ISBN:978-1-4213-6982-2)

- Miyabi: Yukio Mishima (みやび 三島由紀夫) (2005), a documentary film directed by Chiyoko Tanaka[261]

- 11·25 jiketsu no hi: Mishima Yukio to wakamonotachi (2012), a film directed by Kōji Wakamatsu[262]

- Mishima Yukio vs University of Tokyo Zenkyoto members: a truth of 50th year (三島由紀夫vs東大全共闘〜50年目の真実〜) (2020), a documentary film directed by Keisuke Toyoshima (豊島圭介)[263]

- Music

- Harakiri, by Péter Eötvös (1973). An opera music composed based on the Japanese translation of István Bálint's poetry Harakiri that inspired by Mishima's hara-kiri. This work is included in Ryoko Aoki (青木涼子)'s album Noh x Contemporary Music (能×現代音楽) on June 2014.[264]

- String Quartet No.3, "Mishima", by Philip Glass. A reworking of parts of his soundtrack for the film Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters it has a duration of 18 minutes.

- Death and Night and Blood (Yukio), a song by the Stranglers from the Black and White album (1978) (Death and Night and Blood is the phrase from Mishima's novel Confessions of a Mask)[265]

- Forbidden Colours, a song on Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence soundtrack by Ryuichi Sakamoto with lyrics by David Sylvian (1983). (Inspired by Mishima's novel Forbidden Colors)[266]

- Sonatas for Yukio – C.P.E. Bach: Harpsichord Sonatas, by Jocelyne Cuiller (2011).[264] A program composed of Bach sonatas for each scene of the novel "Spring Snow".

- Play

- Yukio Mishima, a play by Adam Darius and Kazimir Kolesnik, first performed at Holloway Prison, London, in 1991, and later in Finland, Slovenia and Portugal.

- M, a ballet spectacle work homage to Mishima by Maurice Béjart in 1993[267]

- Manga, Game

- Shin Megami Tensei by Atlus (1992) – A character Gotou who started a coup in Ichigaya, modeled on Mishima.

- Tekken by Namco (1994) – Mishima surname comes from Yukio Mishima, and a main character Kazuya Mishima's way of thinking was based on Mishima.

- Jakomo Fosukari(Jakomo Fosukari (ジャコモ・フォスカリ)) by Mari Yamazaki (2012) – The characters modeled on Mishima and Kōbō Abe appears in.[268][264]

- Poem

- Harakiri, by István Bálint.[264]

- Grave of Mishima (Yukio Mishima no haka (ユキオ・ミシマの墓)) by Pierre Pascal (1970) – 12 Haiku poems and three Tanka poems. Appendix of Shinsho Hanayama (花山信勝)'s book translated into French.[269]

- Art

- Kou (Kou (恒)) by Junji Wakebe (分部順治) (1976) – Life-sized male sculpture modeled on Mishima. The work was requested by Mishima in the fall of 1970, he went to Wakebe's atelier every Sunday. It was exhibited at the 6th Niccho Exhibition on 7 April 1976.[270]

- Season of fiery fire / Requiem for someone: Number 1, Mishima (Rekka no kisetsu/Nanimonoka eno rekuiemu: Sono ichi Mishima (烈火の季節/なにものかへのレクイエム・その壱 ミシマ)) and Classroom of beauty, listen quietly: bi-class, be quiet" (Bi no kyositsu, seicho seyo (美の教室、清聴せよ)) by Yasumasa Morimura (2006, 2007) – Disguise performance as Mishima[271][264]

- Objectglass 12 and The Death of a Man (Otoko no shi (男の死)) by Kimiski Ishizuka (石塚公昭) (2007, 2011) – Mishima dolls[272][264]

See also

- Hachinoki kai – a chat circle to which Mishima belonged.

- Japan Business Federation attack – an incident in 1977 involving four persons (including one former Tatenokai member) connected by the Mishima incident.

- Kosaburo Eto – Mishima states that he was impressed with the seriousness of Eto's self-immolation, "the most intense criticism of politics as a dream or art."[273]

- Kumo no kai – a literary movement group presided over by Kunio Kishida in 1950–1954, to which Mishima belonged.

- Mishima Yukio Prize – a literary award established in September 1987.

- Phaedo – the book Mishima had been reading in his later years.

- Suegen – a traditional authentic Japanese style restaurant in Shinbashi that is known as the last dining place for Mishima and four Tatenokai members (Masakatsu Morita, Hiroyasu Koga, Masahiro Ogawa, Masayoshi Koga).

Notes

- ↑ Pronunciations: UK: /ˈmɪʃɪmə/, US: /-mɑː, ˈmiːʃimɑː, mɪˈʃiːmə/,[2][3][4][5] Japanese: [miɕima].

- ↑ Yoritaka's eldest son was Matsudaira Yorinori (松平頼徳) who died at the age of 33 when he was ordered to commit seppuku by the shogunate during the Tengutō no ran (天狗党の乱, "Mito Rebellion"), because he was sympathetic to Tengu-tō (天狗党)'s Sonnō jōi.[22]

- ↑ Mishima had told about his bloodline that; "I'm a descendant of the peasants and samurais, and my way of working is like a most hard-working peasant."[26]

- ↑ At the end of this debut work, a limpid "tranquility" is drawn, and it is often pointed out by some literature researchers that it has something in common with the ending of Mishima's posthumous work The Sea of Fertility.[34][35]

- ↑ Kuniko Mitani, the sister of Makoto Mitani (三谷信), would become the model for "Sonoko" in Confessions of a Mask (仮面の告白, Kamen no kokuhaku). Mishima wrote in a letter to an acquaintance that "I wouldn't have lived if I didn't write about her."[61]

- ↑ In the occupation of Japan, SCAP executed "sword hunt", and 3 million swords which had been owned by the Japanese people were confiscated. Further Kendo was banned, and even when barely allowed in the form of "bamboo sword competition", SCAP severely banned kendo shouts,[64] and, they banned Kabuki which had the revenge theme, or inspired the samurai spirit.[65]

- ↑ In 1956, the Japanese government had issued an economic white paper that famously declared, "The postwar is now over" (Mohaya sengo de wa nai).[78]

- ↑ As for the evaluation of Fukushima's book, it is attracting attention as material for learning about Mishima's friendships when writing Forbidden Colors; however, there were criticisms that this book was confused readers, because it was written the real names of all characters like a nonfiction, at the same time, Fukushima specified "a novel about Mr. Yukio Mishima", "this work", "this novel" in the introduction and epilogue[120] or it was advertised as "an autobiographical novel", so the publisher didn't have the confidence to say that everything was true; the only valuable accounts in this book were Mishima's letters.[116] Also there were vitriolic criticisms that these contents of book was insignificant compared to its exaggerated advertising, or it was pointed out that there were contradictions and unnatural adaptations like a made-up story in the neighborhood of gay bars.[116] Gō Itasaka, who thinks Mishima was homosexual, said about this book as below, "Fukusima's petty touch only described a petty Mishima, Mishima was sometimes vulgar, but was never a humble man. The complex which Mishima himself kept holding like a poison in his own(is like available for use at any time), was not always an aversion for him."[116] Jakucho Setouchi and Akihiro Miwa said about this book and Fukusima as below, "It's the worst way for a man or a woman to write bad words about someone you once liked, and Fukusima is ingrateful, because he had been taken care of in various ways when he was poor, by Mishima and his parents. "[121]

- ↑ On one occasion, when Mishima missed the new issue of Weekly Shōnen Magazine on its release day because he had been shooting the movie Black Lizard, at midnight he suddenly appeared in the magazine's editorial department and demanded, "I want you to sell to me the Weekly Shōnen Magazine just released today."[135]

- ↑ After that, Disneyland became Mishima's favorite. And, in the New Year of 1970, the year he was determined to die, he had wanted the whole family with children to revisit the fantasy theme park. But the dream didn't come true because of his wife's objection that she wanted to do it after the completion of The Sea of Fertility.[142]