Biology:Woma python

| Woma python | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Pythonidae |

| Genus: | Aspidites |

| Species: | A. ramsayi

|

| Binomial name | |

| Aspidites ramsayi (Macleay, 1882)

| |

| |

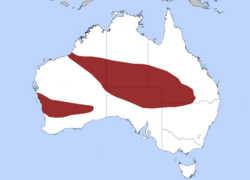

| Distribution of the woma | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

The woma python (Aspidites ramsayi), also known commonly as Ramsay's python, the sand python,[3][4][5][6] and simply the woma,[7] is a species of snake in the family Pythonidae, endemic to Australia . Once common throughout Western Australia, it has become critically endangered in some regions.

Taxonomy

William John Macleay originally described the species in 1882 as Aspidiotes ramsayi. The specific name, ramsayi, is in honor of Australian zoologist Edward Pierson Ramsay.[8][9]

This is one of two species of Aspidites, the pitless pythons, an Australian genus of the family Pythonidae. The generic name, Aspidites, translates to "shield bearer" in reference to the symmetrically shaped head scales.[10]

Description

Adults of A. ramsayi typically are around 1.5 m (4.5 feet) in total length (including tail). The head is narrow, and the eyes are small. The body is broad and flattish in profile, while the tail tapers to a thin point.

The dorsal scales are small and smooth, with 50-65 rows at midbody. The ventral scales are 280-315 in number, with an undivided anal plate, and 40-45 mostly single subcaudal scales. Some of the posterior subcaudals may be irregularly divided.

The dorsal color may be pale brown to nearly black. The pattern consists of a ground color that varies from medium brown and olive to lighter shades of orange, pink, and red, overlaid with darker striped or brindled markings. The belly is cream or light yellow with brown and pink blotches. The scales around the eyes are usually a darker color than the rest of the head.

Aspidites ramsayi may reach a total length of 2.3 m (7.5 ft), with a snout-vent length (SVL) of 2.0 m (6.6 ft).

Snakes of the genus Aspidites lack the heat-sensing pits of all other pythons. A. ramsayi is similar in appearance to A. melanocephalus, but without an obvious neck. The coloration or desire to locate this species may lead to confusion with the venomous species Pseudonaja nuchalis, commonly known as the gwardar.[3]

Distribution and habitat

Aspidites ramsayi lives in the west and center of Australia , from Western Australia through southern Northern Territory and northern South Australia to southern Queensland and northwestern New South Wales. Its range may be discontinuous. The type locality is "near Forte Bourke" [New South Wales, Australia].[2]

The range in Southwest Australia extends from Shark Bay, along the coast and inland regions, and was previously common on sandplains. The species was recorded in regions to the south and east, with once extensive wheatbelt and goldfield populations.[3]

Conservation status

A. ramsayi is classified as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.[1]

The Adelaide Zoo in South Australia is co-ordinating a captive breeding program for the species, and the offspring raised have been released into the Arid Recovery Reserve in the states north with no success due to mulga snake, Pseudechis australis, predation.

Many populations in the southwest of the country, since the 1960s, became critically endangered by altered land use. The sharp decline in numbers, without an authenticated record since 1989, was most notable in the Wheatbelt areas.[3]

Behavior

Aspidites ramsayi is largely nocturnal. By day this snake shelters in hollow logs or under leaf debris. When travelling across hot sands or other surfaces it lifts its body off the ground and reaches far forward before pushing off the ground again, having only a few inches of its body touching the ground at a time.

Feeding

Aspidites ramsayi preys upon a variety of terrestrial vertebrates such as small mammals, ground birds, and lizards. It catches much of its prey in burrows where there is not enough room to maneuver coils around the prey; instead, the woma pushes a loop of its body against the animal to pin it against the side of the burrow. Many adult womas are covered in scars from retaliating rodents as this technique doesn't kill prey as quickly as normal constriction.[11]

Although this species will take warm-blooded prey when offered, A. ramsayi preys mainly on reptiles. Perhaps due to this, species within the genus Aspidites lack the characteristic heat sensing pits of pythons, although they possess an equivalent sensory structure in the rostral scale.[12]

Reproduction

Aspidites ramsayi is oviparous, with five to 20 eggs per clutch. Females remain coiled around their eggs until they hatch, with the incubation period lasting 2–3 months. An adult female about 4–5 years old and 5 ft (about 1.5 m) in total length usually lays about 11 eggs.

Captivity

Considered to be more active than many pythons, as well as being a very docile and "easy to handle" snake, the woma is highly sought after in the reptile and exotic pet trade. It is one of the hardiest python species in captivity, often enthusiastically accepting prey and other items. One made headlines in May 2015 for requiring surgery to remove the feeding tongs it had swallowed as well as its meal.[13] This snake will breed in captivity. [citation needed]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Bruton, M.; Wilson, S.; Shea, G.; Ellis, R.; Venz, M.; Hobson, R.; Sanderson, C. (2017). "Aspidites ramsayi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T2176A83765377. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T2176A83765377.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/2176/83765377. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 McDiarmid RW, Campbell JA, Touré TA (1999). Snake Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, Volume 1. Washington, District of Columbia: Herpetologists' League. 511 pp. ISBN:1-893777-00-6 (series). ISBN:1-893777-01-4 (volume).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Reptiles and Frogs in the Bush: Southwestern Australia. University of Western Australia Press. 2007. pp. 237, 238. ISBN 978-1-920694-74-6.

- ↑ O'Connor F (2008). Western Australian Reptile Species. Birding Western Australia. Accessed 20 September 2007.

- ↑ "Aspidites ramsayi ". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=634770.

- ↑ Mehrtens JM (1987). Living Snakes of the World in Color. New York: Sterling Publishers. 480 pp. ISBN:0-8069-6460-X.

- ↑ Bruton M, Wilson S, Shea G, Ellis R, Venz M, Hobson R, Sanderson C (2017). "Aspidites ramsayi ". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T2176A83765377. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T2176A83765377.en. Downloaded on 02 January 2019.

- ↑ O'Shea M (2007). Boas and Pythons of the World. London: New Holland Publishers Ltd. 160 pp. ISBN:9781845375447.

- ↑ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN:978-1-4214-0135-5. (Aspidites ramsayi, p. 216).

- ↑ Cerveny, Shannon N. S.; Garner, Michael M.; D'Agostino, Jennifer J.; Sekscienski, Stacey R.; Payton, Mark E.; Davis, Michelle R. (December 2012). "Evaluation of Gastroscopic Biopsy for Diagnosis Ofcryptosporidiumsp. Infection in Snakes". Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 43 (4): 864–871. doi:10.1638/2012-0143.1. ISSN 1042-7260. PMID 23272355. https://bioone.org/journals/Journal-of-Zoo-and-Wildlife-Medicine/volume-43/issue-4/2012-0143.1/EVALUATION-OF-GASTROSCOPIC-BIOPSY-FOR-DIAGNOSIS-OF-CRYPTOSPORIDIUM-SP-INFECTION/10.1638/2012-0143.1.full.

- ↑ "Woma python (Aspidites ramsayi )". arkive.org

- ↑ Westhoff G, Collin SP (2008). A new type of infrared sensitive organ in the python Aspidites sp. (Abstract). 6th World Congress of Herpetology. Manaus.

- ↑ McCurdy, Euan (2015). "Winston the python bites off more than he can chew". (http://www.cnn.com/2015/05/15/asia/python-swallows-barbeque-tongs/

Further reading

- Boulenger GA (1893). Catalogue of the Snakes in the British Museum (Natural History). Volume I., Containing the Families ... Boidæ ... London: Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History). (Taylor and Francis, printers). London. xiii + 448 pp. + Plates I-XXVIII. (Aspidites ramsayi, new combination, p. 92).

- Cogger HG (2014). Reptiles and Amphibians of Australia, Seventh Edition. Clayton, Victoria, Australia: CSIRO Publishing. xxx + 1,033 pp. ISBN:978-0643100350.

- Macleay W (1882). "Descriptions of two new Snakes". Proc. Linnean Soc. New South Wales (Series 1) 6: 811-813. (Aspidiotes ramsayi, new species, p. 813).

- Wilson, Steve; Swan, Gerry (2013). A Complete Guide to Reptiles of Australia, Fourth Edition. Sydney: New Holland Publishers. 522 pp. ISBN:978-1921517280.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Woma python. |

- Aspidites ramsayi at the Reptarium.cz Reptile Database. Accessed 19 September 2007.

Wikidata ☰ Q304941 entry

|