Earth:Mount Moulton

| Mount Moulton | |

|---|---|

Aerial view of Mount Moulton from the south | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 3,078 m (10,098 ft) |

| Coordinates | [ ⚑ ] : 76°03′S 135°08′W / 76.05°S 135.133°W |

| Geography | |

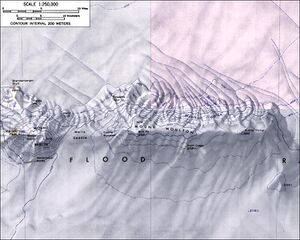

| Parent range | Flood Range |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Shield volcano |

| Volcanic field | Marie Byrd Land Volcanic Province |

Mount Moulton is a 40-kilometre-long (25 mi) complex of ice-covered shield volcanoes, standing 25 kilometres (16 mi) east of Mount Berlin in the Flood Range, Marie Byrd Land, Antarctica. It is named for Richard S. Moulton, chief dog driver at West Base. The volcano is of Pliocene age and is presently inactive.

The Prahl Crags are located on the southern slopes of Mount Moulton and are part of a caldera. There, an exposed area of blue ice can be found; this ice contains tephra layers from mainly neighbouring Mount Berlin volcano and some of the ice is almost half a million years old.

Geology and geomorphology

Mount Moulton lies in Marie Byrd Land[1] of Western Antarctica and in the region of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. It is part of a system of volcanoes including Mount Berlin, Mount Takahe and Mount Waesche as well as of recently active subglacial volcanism.[2] The volcano is named for Richard S. Moulton, chief dog driver of the United States Antarctic Service Expedition;[3] the western end of the Flood Range[3] where Mount Moulton lies[4] was visited by this expedition in December 1940.[3] Other field expeditions took place in 1967-1968, 1977-1978, 1993-1994 and 1999-2000.[5]

The volcano appears to be of Pliocene age[6] and there is no evidence that it was glaciated during its eruptions.[7] Only a few outcrops of Mount Moulton have been dated and these yield ages of 5.3 million years,[8] with further age estimates of 4.9 – 4.7 million years ago,[9] 5.9 million years ago[10] and 1.04 ± 0.04 million years ago[7] at Gawne Nunatak,[11] which is a parasitic cone.[12] There is no evidence of eruptive or thermal activity unlike at its neighbour[8] Mount Berlin.[2] Earthquakes have been recorded at Mount Moulton and are either of volcano-tectonic origin or due to the movement of ice along the flanks of the volcano.[13]

The mountain is 3,078 metres (10,098 ft) high,[6] rising about 1.7 kilometres (1.1 mi) above the ice surface on its northern flank,[14] and located within the Flood Range; Mount Berlin lies across the c. 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) wide, high-elevation[15] Wells Saddle[8] 25 kilometres (16 mi) to the west[16] and Kohler Dome is east of Moulton.[8] Even farther east lie Mount Bursey, Mount Andrus, Mount Kosciuszko and Mount Kauffman, in the Ames Range.[4] Mount Moulton is an obstacle to ice flow in the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, which has piled up on the mountain and is about 800 metres (2,600 ft) higher on the upstream side.[17]

Mount Moulton is formed by a 40-kilometre-long (25 mi) complex of glaciated but largely uneroded[8] shield volcanoes[14] with two or possibly three[17] ice-filled calderas,[8] each of which is about 5–7 kilometres (3.1–4.3 mi) wide.[12] The calderas are 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) apart[14] and located at the Prahl Crags, Britt Peak and potentially Kohler Dome localities.[12] Additionally the Prahl Crags – remnants of the former caldera rim – are found south, Gawne Nunatak west, Edwards Spur northeast and the Moulton Icefalls on the northern side of the mountain.[8] The total volume of the complex is about 325 cubic kilometres (78 cu mi),[14] comparable to that of Mount Shasta in the Cascade Range, and is one of the largest volcanoes in the Flood Range and Ames Range.[9] Only the western part of the Mount Moulton emerges from the ice.[18]

Volcanic rocks found at Mount Moulton include pantellerite,[6] phonolite[19] and trachyte;[14] phenocryst phases found in the pantellerite include aenigmatite, anorthoclase, fayalite, hedenbergite, ilmenite and quartz.[20]

Blue ice field

A blue ice field has formed within the caldera of Mount Moulton behind the Prahl Crags, and contains ice almost 500,000 years old.[8] It is the oldest dated ice in West Antarctica[21] and much older than ice found elsewhere in West Antarctic ice cores.[22] Such blue ice fields like those found at Mount Moulton form when glaciers run into an obstacle – in this case the Prahl Crags – and part of the ice starts moving vertically as it undergoes ablation processes like sublimation.[23] In the case of Mount Moulton, this outcrop of ice is about 600 metres (2,000 ft) long.[1] The ice has been used to reconstruct past climate states in West Antarctica, including the beginning and end of the last interglacial,[24] and shows evidence that the West Antarctic Ice Sheet collapsed during that interglacial.[25]

In addition, recognizable tephra layers are found in this ice[22] and appear to originate from explosive eruptions of volcanoes such as Mount Berlin, Mount Takahe and Mount Waesche,[26] although some may come from parasitic vents of Mount Berlin and Mount Moulton.[12] These tephra layers at Mount Moulton crop out in parallel layers[27] and geochemical traits indicate an origin at Mount Berlin although some layers may have been erupted from mafic volcanoes at Mount Moulton and Mount Berlin.[28] Furthermore, the appearance of the deposits indicates that the eruptions of Mount Berlin were highly explosive.[29] Most likely they eventually fell onto the ice of Mount Moulton, were incorporated in it and then transported downward to the blue ice field.[30]

See also

- List of volcanoes in Antarctica

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Korotkikh et al. 2011, p. 1941.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Esser, McIntosh & Dunbar 2008, p. 796.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 LeMasurier 2013, p. 226.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 LeMasurier, W. E.; Rex, D. C. (1989). "Evolution of linear volcanic ranges in Marie Byrd Land, West Antarctica". Journal of Geophysical Research 94 (B6): 7226. doi:10.1029/JB094iB06p07223. Bibcode: 1989JGR....94.7223L.

- ↑ Wilch, McIntosh & Panter 2021, p. 520.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 LeMasurier 2013, p. 151.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Wilch, McIntosh & Panter 2021, p. 522.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 Esser, McIntosh & Dunbar 2008, p. 797.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 LeMasurier et al. 2011, p. 1178.

- ↑ Dunbar, McIntosh & Wilch 1999, p. 1572.

- ↑ Wilch, McIntosh & Panter 2021, p. 555.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Wilch, McIntosh & Panter 2021, p. 557.

- ↑ Lough, A. C.; Barcheck, C. G.; Wiens, D. A.; Nyblade, A.; Aster, R. C.; Anandakrishnan, S.; Huerta, A. D.; Wilson, T. J. (1 December 2012). "Subglacial volcanic seismicity in Marie Byrd Land detected by the POLENET/ANET seismic deployment". AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts 41: T41B–2587. Bibcode: 2012AGUFM.T41B2587L.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 LeMasurier 2013, p. 225.

- ↑ Wilch, McIntosh & Panter 2021, p. 554.

- ↑ Smellie, J. L. (1 July 1999). "The upper Cenozoic tephra record in the south polar region: a review". Global and Planetary Change 21 (1): 53. doi:10.1016/S0921-8181(99)00007-7. ISSN 0921-8181. Bibcode: 1999GPC....21...51S.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Wilch, McIntosh & Panter 2021, p. 521.

- ↑ González-Ferrán, Oscar; González-Bonorino, Felix (1972). "The volcanic ranges of Marie Byrd Land between long. 100 and 140 W.". Antarctic Geology and Geophysics. 261. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget. p. 262.

- ↑ LeMasurier 2013, p. 9.

- ↑ LeMasurier et al. 2011, p. 1182.

- ↑ Dunbar, McIntosh & Wilch 1999, p. 1579.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Esser, McIntosh & Dunbar 2008, p. 798.

- ↑ Esser, McIntosh & Dunbar 2008, p. 810.

- ↑ Korotkikh et al. 2011, p. 1946.

- ↑ Steig, Eric J.; Huybers, Kathleen; Singh, Hansi A.; Steiger, Nathan J.; Ding, Qinghua; Frierson, Dargan M. W.; Popp, Trevor; White, James W. C. (28 June 2015). "Influence of West Antarctic Ice Sheet collapse on Antarctic surface climate: CLIMATE RESPONSE TO WAIS COLLAPSE" (in en). Geophysical Research Letters 42 (12): 4867. doi:10.1002/2015GL063861.

- ↑ Esser, McIntosh & Dunbar 2008, p. 799.

- ↑ Esser, McIntosh & Dunbar 2008, p. 803.

- ↑ Esser, McIntosh & Dunbar 2008, p. 808.

- ↑ Dunbar, McIntosh & Wilch 1999, p. 1576.

- ↑ Esser, McIntosh & Dunbar 2008, p. 811.

Sources

- Dunbar, N. W.; McIntosh, W. C.; Wilch, T. I. (1 October 1999). "Late Quaternary volcanic activity in Marie Byrd Land: Potential 40Ar/39Ar-dated time horizons in West Antarctic ice and marine cores" (in en). GSA Bulletin 111 (10): 1563–1580. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1999)111<1563:LQVAIM>2.3.CO;2. ISSN 0016-7606. Bibcode: 1999GSAB..111.1563W.

- Esser, Richard P.; McIntosh, William C.; Dunbar, Nelia W. (1 July 2008). "Physical setting and tephrochronology of the summit caldera ice record at Mount Moulton, West AntarcticaMount Moulton tephrochronology" (in en). GSA Bulletin 120 (7–8): 796–812. doi:10.1130/B26140.1. ISSN 0016-7606.

- Korotkikh, Elena V.; Mayewski, Paul A.; Handley, Michael J.; Sneed, Sharon B.; Introne, Douglas S.; Kurbatov, Andrei V.; Dunbar, Nelia W.; McIntosh, William C. (1 July 2011). "The last interglacial as represented in the glaciochemical record from Mount Moulton Blue Ice Area, West Antarctica". Quaternary Science Reviews 30 (15): 1940–1947. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2011.04.020. ISSN 0277-3791. Bibcode: 2011QSRv...30.1940K.

- LeMasurier, Wesley E.; Choi, Sung Hi; Kawachi, Y.; Mukasa, Samuel B.; Rogers, N. W. (1 December 2011). "Evolution of pantellerite-trachyte-phonolite volcanoes by fractional crystallization of basanite magma in a continental rift setting, Marie Byrd Land, Antarctica" (in en). Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 162 (6): 1175–1199. doi:10.1007/s00410-011-0646-z. ISSN 1432-0967. Bibcode: 2011CoMP..162.1175L.

- LeMasurier, W. E. (2013), "B. Marie Byrd Land" (in en), Volcanoes of the Antarctic Plate and Southern Oceans, Antarctic Research Series, 48, American Geophysical Union (AGU), pp. 146–255, doi:10.1029/ar048p0146, ISBN 9781118664728

- Wilch, T. I.; McIntosh, W. C.; Panter, K. S. (1 January 2021). "Chapter 5.4a Marie Byrd Land and Ellsworth Land: volcanology" (in en). Geological Society, London, Memoirs 55 (1): 515–576. doi:10.1144/M55-2019-39. ISSN 0435-4052. https://mem.lyellcollection.org/content/55/1/515.abstract.

Further reading

|