Engineering:Heinkel He 280

| He 280 | |

|---|---|

| |

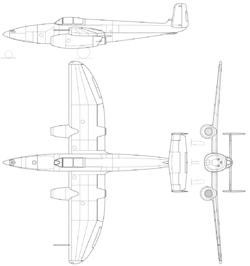

| Heinkel He-280 illustration | |

| Role | Fighter |

| Manufacturer | Heinkel |

| Designer | Robert Lusser |

| First flight | 22 September 1940 |

| Status | Cancelled |

| Produced | 1940–1943 |

| Number built | 9 |

The Heinkel He 280 was an early turbojet-powered fighter aircraft designed and produced by the German aircraft manufacturer Heinkel. It was the first jet fighter to fly in the world.

The He 280 harnessed the progress made by Hans von Ohain's novel gas turbine propulsion and by Ernst Heinkel's work on the He 178, the first jet-powered aircraft in the world. Heinkel placed great emphasis on research into high-speed flight and on the value of the jet engine; after the He 178 had met with indifference from the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (RLM) (the German Reich Aviation Ministry), the company opted to start work on producing a jet fighter during late 1939. Incorporating a pair of turbojets, for greater thrust, these were installed in a mid-wing position. It also had a then-uncommon tricycle undercarriage while the design of the fuselage was largely conventional.

During the summer of 1940, the first prototype airframe was completed; however, it was unable to proceed with powered test flights due to development difficulties with the intended engine, the HeS 8. Thus, it was initially flown as a glider until suitable engines could be made available six months later. The lack of state support protracted engine development, and thus setting back work on the He 280; nevertheless, it is believed that the fighter could have been made operational earlier than the competing Messerschmitt Me 262, and offered some advantages over it. On 22 December 1942, a mock dogfight performed before RLM officials saw the He 280 demonstrate its vastly superior speed over the piston-powered Focke-Wulf Fw 190; shortly thereafter, the RLM finally opted to place an order for 20 pre-production test aircraft to precede a batch of 300 production standard aircraft.

However, engine development continued to be a thorn in the side of the He 280 program. During 1942, the RLM had ordered Heinkel to abandon work on both the HeS 8 and HeS 30 to focus on the HeS 011. As the HeS 011 was not expected to be available for some time, Heinkel selected the rival BMW 003 powerplant; however, this engine was also delayed. Accordingly, the second He 280 prototype was re-engined with Junkers Jumo 004s. On 27 March 1943, Erhard Milch, Inspector-General of the Luftwaffe, ordered Heinkel to abandon work on the He 280 in favour of other efforts. The reason for this cancellation has been attributed to combination of both technical and political factors; the similar role of the Me 262 was certainly influential in the decision.[1] Accordingly, only the nine test aircraft were ever built, at no point did the He 280 ever attain operational status or see active combat.[2]

Development

Background

During the late 1930s, the Heinkel company had developed the He 178, the world's first turbojet-powered aircraft; successfully flying the aircraft for the first time on 27 August 1939.[3][4] However, an aerial demonstration of the He 178 had apparently failed to interest attending officials from the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (RLM) (the German Reich Aviation Ministry) either in the aircraft itself or jet propulsion in general.[5][6] Unknown to Heinkel, the Reich Air Ministry had already begun work on discretely developing its own jet technology independently of his company's efforts.[7][8]

Despite having been unable to secure state backing for further work, Heinkel was undeterred in the potential value of the turbojet.[9] Instead, the company independently decided to undertake work on what would become the He 280 during late 1939. This internal project to develop a jet-powered fighter aircraft, which had been started under the designation He 180, was headed by the German aeronautical designer Robert Lusser.[10][11] The project was greatly aided by the earlier He 178 programme, which had not only served as a proof of concept but also yielded invaluable data gathered from flight testing;[12] however, the design of the He 178 was deemed to be unsuitable for further development; particularly as mounting the engine within the fuselage had been judged to be impractical.[13]

For the He 280, a pair of turbojets were used, each one installed in a mid-wing position, which was viewed as a more straightforward arrangement.[13] Despite its novel propulsion, the design had adopted numerous relatively orthodox features, such as a typical Heinkel fighter fuselage, semi-elliptical wings, and a dihedralled tailplane with twin fins and rudders. The He 280 was furnished with a tricycle undercarriage that had very little ground clearance;[14][15] this arrangement was considered by some officials to be too frail for the grass or dirt airfields of the era; however, the tricycle layout eventually gained acceptance. One particularly groundbreaking feature incorporated onto the He 280 was its ejection seat, which was powered by compressed air; it was not only the first aircraft to be equipped with one but would also be the first aircraft to successfully employ one in a genuine emergency.[10][16] In contrast to the Messerschmitt Me 262, another German jet fighter, the He 280 had a smaller footprint and is believed to have been more maintainable.[17]

Test flying

During the summer of 1940, the first prototype airframe was completed, however, the HeS 8 turbojets that were intended to power it had encountered considerable production difficulties.[18] On 22 September 1940, while work on the engine continued, the first prototype commenced glide tests, having been fitted with ballasted pods in place of its engines,[14][18] towed behind a He 111. It was another six months before Fritz Schäfer flew the second prototype under its own power, on 30 March 1941. After landing, Schäfer reported to Heinkel that, while somewhat difficult to exercise control during turns, an experienced pilot would have an easy time flying the He 280.[19]

On 5 April 1941, Paul Bader performed an exhibition flight before various Nazi officials, including Ernst Udet, General-Ingenieur Lucht, Reidenbach, Eisenlohr and others. However, the RLM eventually favored development of the Me 262, a rival jet-powered fighter.[20] Yet, Heinkel was given Hirth Motoren for continued turbine development.[21] One benefit of the He 280 which did impress Germany's political leadership was the fact that the jet engines could burn kerosene, a fuel that required much less expense and refining than the high-octane fuel used by piston-engine aircraft. However, government funding was lacking at the critical stage of initial development; the aviation author Robert Dorr largely attributes this lack of support to the personal opposition voiced by Udet.[16]

Over the next year, progress was slow due to the ongoing engine problems. A second engine design, the HeS 30 was also under development, both as an interesting engine in its own right and as a potential replacement for the HeS 8. In the meantime, alternative powerplants were considered, including the Argus As 014 pulsejet that powered the V-1 flying bomb.[22] It was proposed that up to eight would be used.[22]

By the end of 1942, however, the third prototype was fitted with refined versions of the HeS 8 engine and was ready for its next demonstration. On 22 December, a mock dogfight was staged for RLM officials in which the He 280 was matched against a piston-powered Focke-Wulf Fw 190 fighter, in which the jet demonstrated its vastly superior speed, completing four laps of an oval course before the Fw 190 could complete three.[16][23] Finally, at this point the RLM became interested and placed an order for 20 pre-production test aircraft that were to be followed by a batch of 300 production standard aircraft.

Engine troubles and cancellation

Engine problems continued to plague the project. During 1942, the RLM had ordered Heinkel to abandon work on both the HeS 8 and HeS 30 to focus all development on a follow-on engine, the HeS 011, which proved to be a more advanced and problematic design.[citation needed] Meanwhile, the first He 280 prototype was re-equipped with pulsejets,[22] and towed aloft to test them. Bad weather caused the aircraft to ice up before the jets could be tested; the situation led to pilot Helmut Schenk becoming the first person to put an ejection seat to use.[16] While the seat worked perfectly, the aircraft was lost and never recovered.

As the HeS 011 was not expected to be available for some time, Heinkel selected the rival BMW 003 powerplant; however, this engine also suffered problems and delays. Accordingly, the second He 280 prototype was re-engined with Junkers Jumo 004s.[18] The following three airframes were earmarked for the BMW motor which would never become available in actuality. The Jumo engines were considerably larger and heavier than the HeS 8 that the aircraft had been designed for, and while it flew well enough on its first powered flights from 16 March 1943, it was clear that this engine was unsuitable.[citation needed] The aircraft was slower and generally less efficient than the Me 262.[14]

Less than two weeks later, on 27 March, Erhard Milch, Inspector-General of the Luftwaffe, ordered Heinkel to abandon work on the He 280 to instead focus his company's attention on bomber development and construction. The termination of the project has been attributed to multiple factors. A major contributor was competition from the Jumo 004-powered Me 262, which appeared to possess most of the qualities of the He 280, but had the advantage of being better matched to its engine. Yet it was believed that the He 280 could have been in service sooner and may have been useful even just as a stopgap measure for the Me 262.[24] The aviation authors Tim Heath and Robert Dorr both note that, in light of Heinkel having become unpopular amongst influential Nazis while Willy Messerschmitt was a favoured figure, there were political factors at play in the cancellation of the He 280.[1][25] Heinkel remained interested in jet propulsion and sought out other opportunities to design aircraft harnessing such engines; this would lead to the single-engined Heinkel He 162 that would be selected as the winner of the Emergency Fighter Program in October 1944.[26][27]

Prototypes

- He 280 V1

-

- Stammkennzeichen-coded as "DL+AS".

- 1940-09-22: First flight.

- 1942-01-13: Crashed due to control failure. Pilot ejected safely.

- He 280 V2

-

- Coded as "GJ+CA".

- 1941-03-30: First flight.

- 1943-06-26: Crashed due to engine failure.

- He 280 V3

-

- Coded as "GJ+CB".

- 1942-07-05: First flight.

- 1945-05: Captured at Heinkel-Sud factory complex at Wien-Schwechat, Austria.

- He 280 V4

-

- Coded as "GJ+CC".

- 1943-08-31: First flight.

- 1944-10: Struck off charge at Hörsching, Austria.

- He 280 V5

-

- Coded as "GJ+CD".

- 1943-07-26: First flight.

- Did not receive any jet engines.

- He 280 V6

-

- Coded as "NU+EA".

- 1943-07-26: First flight.

- powered by Junkers Jumo 109-004A engines

- He 280 V7

-

- Coded as "NU+EB" and "D-IEXM".

- 1943-04-19: First flight.

- Flew a total of 115 towed flights. Flew powered with Heinkel-Hirth 109-001 engines until an engine failure, reverting to a glider.

- He 280 V8

-

- Coded as "NU+EC".

- 1943-07-19: First flight.

- He 280 V9

-

- Coded as "NU+ED".

- 1943-08-31: First flight.

Specifications (He 280 V6)

Data from The Warplanes of the Third Reich,[28] Fighting Hitler's Jets[29]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 10.198 m (33 ft 5.5 in)

- Wingspan: 11.996 m (39 ft 4.3 in)

- Height: 3.1941 m (10 ft 5.75 in)

- Wing area: 21.51 m2 (231.5 sq ft)

- Airfoil: root: 13%; tip: 9%[30]

- Gross weight: 5,205 kg (11,475 lb)

- Powerplant: 2 × Junkers Jumo 109-004A Orkan axial-flow turbojet engines, 8.24 kN (1,852 lbf) thrust each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 752 km/h (467 mph, 406 kn) at sea level

- 818 km/h (508 mph; 441 kn) at 6,000 m (19,685 ft)

- 810 km/h (503 mph; 437 kn) at 8,500 m (27,890 ft)

- Range: 615 km (382 mi, 332 nmi) at 9,000 m (30,000 ft)

- 314 km (195 mi; 170 nmi) at sea level

- Service ceiling: 11,400 m (37,390 ft)

- Rate of climb: 21.2 m/s (4,170 ft/min)

- Thrust/weight: 0.32

Armament

- Guns: 3 × 20 mm MG 151/20 cannon

See also

Related lists

- List of aircraft of World War II

- List of military aircraft of Germany

- List of jet aircraft of World War II

References

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Heath 2022, p. 215.

- ↑ Dorr 2013, p. 48.

- ↑ Koehler 1999, p. 173.

- ↑ "U.S. Jet Engines". Flying 72 (2): 89. February 1963. ISSN 0015-4806. https://books.google.com/books?id=3wMCoejQrNMC&pg=PA89.

- ↑ Koehler 1999, pp. 174–175.

- ↑ History Office 2002, p. 196.

- ↑ Christopher 2013, p. 59.

- ↑ Koehler 1999, pp. 160 note 36, 174 note 78: LC2 Nr. 632/39 g.Kdos vom 12. September 1939 Bundesarchiv-Militaerachiv (BA-MA) 4406-812.

- ↑ Buttler 2019, p. 22.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Christopher 2013, p. 58.

- ↑ Heath 2022, p. 213.

- ↑ "Planes of the German Air Force". Flying 38 (1): 120. January 1946. ISSN 0015-4806. https://books.google.com/books?id=Uz9Tdfe8FWEC&pg=PA120.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Buttler 2019, p. 23.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Jane's Fighting aircraft of World War II (1995 ed.). New York: Military Press. 1989. p. 318. ISBN 0517679647.

- ↑ LePage 2009, p. 283.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Dorr 2013, p. 45.

- ↑ Dorr 2013, p. 46.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Dorr 2013, p. 44.

- ↑ Dorr 2013, pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Dorr 2013, p. 39.

- ↑ Warsitz, Lutz (2008). The First Jet Pilot: The Story of German Test Pilot Erich Warsitz. Barnsley, UK: Pen and Sword aviation. pp. 141–144. ISBN 9781844158188.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Dressel, Joachim; Griehl, Manfred; Menke, Jochen (1991). Heinkel He 280. West Chester, PA, US: Schiffer Military History. p. 15.

- ↑ LePage 2009, p. 284.

- ↑ Dorr 2013, pp. 39, 45.

- ↑ Dorr 2013, p. 43.

- ↑ Dorr 2013, pp. 151–153.

- ↑ Forsyth 2016, p. 15.

- ↑ Green, William (1970). The Warplanes of the Third Reich (1st 1973 reprint ed.). New York, US: Doubleday. pp. 361–365. ISBN 0385057822.

- ↑ Dorr 2013, p. 276-277.

- ↑ Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". https://m-selig.ae.illinois.edu/ads/aircraft.html.

Bibliography

- Buttler, Tony (2019). Jet Prototypes of World War II: Gloster, Heinkel, and Caproni Campini's Wartime Jet Programmes. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781472835994. https://books.google.com/books?id=rf6eDwAAQBAJ.

- Dorr, Robert F. (2013). Fighting Hitler's Jets. Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-4398-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=-nBmAgAAQBAJ&q=Messerschmitt+Me+163+Komet.

- History Office (2002). Splendid Vision, Unswerving Purpose. Aeronautical Systems Center, Air Force Materiel Command. ISBN 0-1606-7599-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=E_GsiMU2sksC&pg=PA196.

- Forsyth, Robert (2016). He 162 Volksjäger Units. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-47281-459-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=_tsODQAAQBAJ&pg=PA11.

- "Harbinger of an Era...The Heinkel He 280". Air International 37 (6): 233–241, 260. November 1989. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Heath, Tim (2022). In Furious Skies: Flying with Hitler's Luftwaffe in the Second World War. Pen and Sword History. ISBN 978-1-5267-8526-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=RWuEEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA220.

- Christopher, John (2013). The Race for Hitler's X-Planes: Britain's 1945 mission to capture secret Luftwaffe technology. The Mill, Gloucestershire, UK: History Press. ISBN 978-0752464572.

- Koehler, H. Dieter (1999). Ernst Heinkel – Pionier der Schnellflugzeuge. Bonn, Germany: Bernard & Graefe. ISBN 978-3-7637-6116-6.

- LePage, Jean-Denis G.G. (2009). Aircraft of the Luftwaffe, 1935-1945: An Illustrated Guide. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-5280-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=hdQBTcscxyQC&pg=PA243.

External links

- He 280 film clips (YouTube, posted on 13 November 2016)

|