Medicine:Bowel resection

| Bowel resection | |

|---|---|

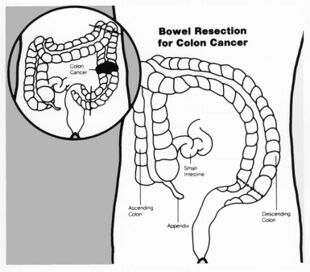

Drawing showing bowel resection for colon cancer | |

| Other names | Enterectomy, Colectomy |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

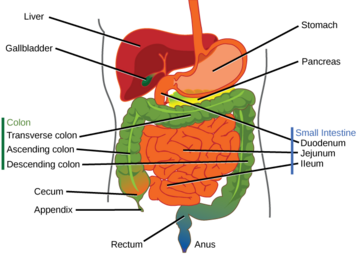

A bowel resection or enterectomy (enter- + -ectomy) is a surgical procedure in which a part of an intestine (bowel) is removed, from either the small intestine or large intestine. Often the word enterectomy is reserved for the sense of small bowel resection, in distinction from colectomy, which covers the sense of large bowel resection. Bowel resection may be performed to treat gastrointestinal cancer, bowel ischemia, necrosis, or obstruction due to scar tissue, volvulus, and hernias. Some patients require ileostomy or colostomy after this procedure as alternative means of excretion.[1] Complications of the procedure may include anastomotic leak or dehiscence, hernias, or adhesions causing partial or complete bowel obstruction. Depending on which part and how much of the intestines are removed, there may be digestive and metabolic challenges afterward, such as short bowel syndrome.

Types

Types of enterectomy are named according to the relevant bowel segment:

| Procedure | Bowel segment | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| duodenectomy | duodenum | |

| Whipple | duodenum and Pancreas | |

| jejunectomy | jejunum | |

| ileectomy | ileum | |

| colectomy | colon |

Surgery

The anatomy and surgical technique for bowel resection varies based on the location of the removed segment and whether or not the surgery is due to malignancy. The below sections describe resection for non-malignant causes. Malignancy may require more extensive tissue resection beyond what is described here.

Bowel resection may be done as an open surgery, with a long incision in the abdomen. It may also be done laparoscopically or robotically by creating several small incisions in the abdomen through which surgical instruments are inserted.[2][3][4] Once the abdomen is accessed by one of these methods the surgery may procede.

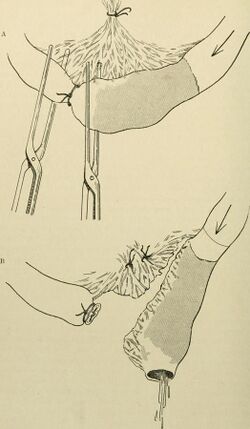

Small bowel resection

Once the abdomen is accessed, the surgeon "runs" the small bowel, viewing the entire small bowel from the ligament of treitz to the ileocecal valve. This allows for total evaluate of the small bowel to identify any and all pathologic sections. Once the area of concern is located, two small holes are created in the mesentery on either end of the segment. These holes are used to place a surgical stapler across the bowel and separate the segment of injured bowel from the healthy bowel on each end. Then bowel is then dissected away from the mesentery. Following this the remaining bowel is observed to verify continued blood flow. After resection the surgeon will create an anastomosis between the two ends of the bowel. Following this the hole in the mesentery created by removing the section of bowel is closed with sutures to prevent internal herniation. The resected section of bowel will then be removed from the abdomen and the abdomen closed. This concludes the procedure.[5][6]

Large bowel resection

The right and left colon sit in the retroperitoneum. To access this space an incision is made along the line of Toldt. The colon is then mobilized from the retroperitoneum. Care is taken to avoid injury to the ureters and duodenum. The surgery then follows the same steps as small bowel resection. However, due to the colon's placement in the retroperitoneum, more dissection is often required to allow for tension free anastomosis.[5][6]

Medical Indications

Cancer

Small bowel or colon cancer may require surgical resection.[7]

Small bowel cancer often presents late in the course due to non-specific symptoms and has poor survival rates. Risk factors for small bowel cancer include genetically inherited polyposis syndromes, age over sixty years, and history of Crohn's or Celiac disease. Cases that present before stage IV show survival benefit from surgical resection with clear margins. It is recommended that surgical resection also include lymph node sampling of a minimum of 12 nodes with some groups extolling more extensive resection. When evaluation determines cancer to be stage IV, surgical intervention is no longer curative, and is only used for symptom relief.[7]

Colon cancer is the third most common cancer and the second most common cause of cancer death in the USA.[8] Due to its prevalence, screening protocols have been created for prevention of disease. Screening colonoscopies with or without polypectomy have been shown to decrease cancer morbidity and mortality.[9] When cancer is more advanced and polypectomy is not possible surgical resection is necessary. Using imaging and pathologic evaluation of resected tissue the tumor may be staged using AJCC stages.[9] Surgical resection of tumors for staging and for curative purposes requires removal of local blood vessel and lymph nodes. Standard lymph node resection includes three consecutive levels of lymph nodes and is known as a D3 lymphadenectomy.[10] In addition to surgery adjuvant chemotherapy may be used to decrease risk of recurrence. Chemotherapy is standard with stage III cancer, case dependant in stage II and palliative in stage IV.[11] Diet high in processed food and surgery drinks has also been shown to increase recurrence of stage III colon cancer.[12]

Bowel obstruction.

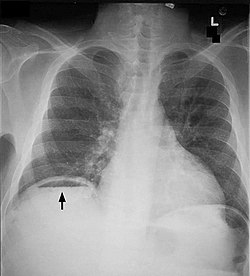

Bowel obstructions are commonly secondary to adhesions, hernias, or cancer. Bowel obstruction can be an emergency requiring immediate surgery. Original testing and imaging include blood tests for electrolyte levels, and abdominal X-rays or CT scans. Treatment often begins with IV fluids to correct electrolyte imbalances. Obstructions may be complicated by ischemia or perforation of the bowel. These cases are surgical emergencies and often require bowel resection to remove the cause of obstruction.[13] Adhesions are a common causes of obstruction, and frequently resolve without surgery.[14]

Other causes of bowel obstruction include volvulus, strictures, inflammation and intussusception. This is not an exhaustive list.

Perforation

Bowel perforation presents with abdominal pain, free air in the abdomen on standing X-ray, and sepsis.[15][16][17] Depending on the cause and size, perforations may be medically or surgically managed. Some common causes of perforation are cancer, diverticulitis, and peptic ulcer disease.

When caused by cancer, bowel perforation typically requires surgery, including resection of blood and lymph supply to the cancerous area when possible. When perforation is at the site of the tumor, the perforation may be contained in the tumor and self resolve without surgery. However, surgery may be required later for the malignancy itself. Perforation before the tumor usually requires immediate surgery due to release of fecal material into the abdomen and infection.[15]

Perforated diverticulitis often requires surgery due to risks of infection or recurrence. Recurrent diverticulitis may required resection even in the absence of perforation. Bowel resection or repair is typically initiated earlier in patients with signs of infection, the elderly, immunocompromised, and those with severe comorbidities.[16]

Peptic ulcer disease may cause perforation of the bowel but rarely requires bowel resection. Peptic ulcer disease is caused by stomach acid overwhelming the protection of mucous production. Risk factors include H. pylori infection, smoking, and NSAID use. The standard treatment is medical management, endoscopy followed by surgical omental patch repair. In rare cases where omental patch fails bowel resection may become necessary.[17]

Traumatic injuries, whether blunt force such as car accidents or penetrating wounds such as gunshot wounds, or stabbings, may also cause bowel perforation or ischemia requiring emergency surgery. Initial evaluation in trauma includes a FAST ultrasound exam followed by contrast CT abdomen in stable patients. The most common bowel injury in trauma is perforation and is repaired rather than resected if the injury involves less than half the bowel circumference and does not involve loss of blood supply. Resection is indicated with more extensive or ischemic injuries.[18]

Ischemia

Bowel ischemia is caused by decreased or absent blood flow through the Celiac, Superior Mesenteric, and Inferior Mesenteric arteries or any combination thereof. Untreated acute mesenteric ischemia can cause bowel necrosis in the affected area. This requires emergent surgery as survival without endovascular or operative intervention is around 50%. Ischemic bowel injury often requires multiple surgeries days apart to allow bowel recovery and increase odds of successful anastomosis.[19]

Complications

Anastomotic leaks/Dehiscence

An anastomotic leak is a fault in the surgical connection between the two remaining sections of bowel after a resection is performed. This allows the bowel contents to leak into the abdomen. Anastomotic leaks may cause infection, abscess development, and organ failure if untreated. Surgical steps are taken to prevent leaks when possible. These include creating anastomoses with minimal tension on the connection and aligning the bowel to prevent twisting of the bowel at the anastomosis. However, it is believed that most leaks are caused by poor healing, not surgical technique. Risk factors for poor healing of anastomosis include obesity, diabetes mellitus, and smoking.[20] Treatment of the leak includes antibiotics, placement of a drain near the leak or developing abscess, stenting of the anastomosis, surgical repair, or creating of an ileostomy or colostomy.[21]

Internal and incisional hernias

Any abdominal surgery may result in an incisional hernia where the abdomen was accessed. Hernias develop when the fascia of the abdominal cavity separates after the surgical closure. This may be due to suture failure, poor wound healing. Other risk factors include obesity and smoking.[22] Smaller closure stitches and the use of mesh when closing open surgeries may decrease the risk of hernia occurrence. However, the use of mesh is limited by the surgery performed and contamination or risk infection.[23]

When colon is resected hernias may form through the mesenteric defect. This is more common with gastric bypass surgery. Internal hernias may cause ischemia and require emergency surgery to resolve.

Adhesions and post-op SBO/BO

A common complication of all abdominal surgeries is adhesions. Adhesions are bands of scar tissue that form after surgery or injury to the abdomen. They can displace or obstruct areas of the bowel. Approximately 1 in 5 emergency surgeries are due to adhesive bowel obstruction. When possible this is managed without surgery with IV fluids, and NG tube to drain the stomach and intestines, and bowel rest (not eating) until the obstruction resolves. If signs of bowel ischemia or perforation are present then emergency surgery is required. Laparoscopic adhesiolysis is the most common surgery used when bowel rest and medical management fail to resolve the obstruction.[14]

Short bowel syndrome

When large amounts of small bowel are resected it can cause short bowel syndrome. Short bowel syndrome is a failure of absorption of nutrients due to resection of portions of the small bowel. It can be limited to a single nutrient or it can be total malabsorption. If the distal ileum is resected it commonly causes a mild form of short bowel syndrome with deficiency of only vitamin B12. When the entire small bowel is resected it can cause chronic complications.[24][25]

The acute form lasts up to one month following bowel resection. Symptoms include diarrhea, malabsorption, and metabolic derangements. This is treated primarily by IV fluids and electrolyte replacement. Acute short bowel syndrome is followed by the adaptation phase which can last up to two years. During this time the small bowel slows movement of bowel contents to allow for more absorption. About half of all patients with short bowel syndrome progress to chronic disease. Chronic short bowel syndrome may require total parenteral nutrition and chronic central line use. These may cause complications such as bacteremia and sepsis. Other complications of short bowel syndrome are chronic diarrhea or high output from the ostomy site, intestinal failure associated liver disease, and electrolyte level abnormalities.[24]

Short bowel syndrome is rare and usually follows extensive ischemic bowel caused by internal hernias, volvulus, or mesenteric ischemia where the remaining small bowel is under 200 cm long.[24][26]

See also

References

- ↑ "Small bowel resection". MedlinePlus: U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/002943.htm.

- ↑ "Large bowel resection: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia" (in en). https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/002941.htm.

- ↑ Contributors, WebMD Editorial. "What Is a Bowel Resection (Partial Colectomy)?" (in en). https://www.webmd.com/colorectal-cancer/bowel-resection.

- ↑ "Small bowel resection Information | Mount Sinai - New York" (in en-US). https://www.mountsinai.org/health-library/surgery/small-bowel-resection.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 L., Swanstrom, Lee (17 October 2013). Mastery of endoscopic and laparoscopic surgery. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1-4698-3120-6. OCLC 1141430815. http://worldcat.org/oclc/1141430815.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 H., Scott-Conner, Carol E. (2015). Scott-Conner & Dawson : Essential Operative Techniques and Anatomy.. Wolters Kluwer. ISBN 978-1-4698-3064-3. OCLC 1044713141. http://worldcat.org/oclc/1044713141.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Chen, Emerson Y.; Vaccaro, Gina M. (September 4, 2018). "Small Bowel Adenocarcinoma". Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery 31 (5): 267–277. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1660482. ISSN 1531-0043. PMID 30186048.

- ↑ Holt, Peter R.; Kozuch, Peter; Mewar, Seetal (2009). "Colon cancer and the elderly: from screening to treatment in management of GI disease in the elderly". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Gastroenterology 23 (6): 889–907. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2009.10.010. ISSN 1532-1916. PMID 19942166.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Freeman, Hugh James (2013-12-14). "Early stage colon cancer". World Journal of Gastroenterology 19 (46): 8468–8473. doi:10.3748/wjg.v19.i46.8468. ISSN 2219-2840. PMID 24379564.

- ↑ Okuno, Kiyotaka (2007). "Surgical treatment for digestive cancer. Current issues - colon cancer". Digestive Surgery 24 (2): 108–114. doi:10.1159/000101897. ISSN 0253-4886. PMID 17446704. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17446704.

- ↑ Leichsenring, Jona; Koppelle, Adrian; Reinacher-Schick, Ank (May 2014). "Colorectal Cancer: Personalized Therapy". Gastrointestinal Tumors 1 (4): 209–220. doi:10.1159/000380790. ISSN 2296-3774. PMID 26676107.

- ↑ Morales-Oyarvide, Vicente; Yuan, Chen; Babic, Ana; Zhang, Sui; Niedzwiecki, Donna; Brand-Miller, Jennie C.; Sampson-Kent, Laura; Ye, Xing et al. (2019-02-01). "Dietary Insulin Load and Cancer Recurrence and Survival in Patients With Stage III Colon Cancer: Findings From CALGB 89803 (Alliance)". Journal of the National Cancer Institute 111 (2): 170–179. doi:10.1093/jnci/djy098. ISSN 1460-2105. PMID 30726946.

- ↑ Jackson, Patrick G.; Raiji, Manish T. (2011-01-15). "Evaluation and management of intestinal obstruction". American Family Physician 83 (2): 159–165. ISSN 1532-0650. PMID 21243991. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21243991.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Tong, Jia Wei Valerie; Lingam, Pravin; Shelat, Vishalkumar Girishchandra (2020). "Adhesive small bowel obstruction - an update". Acute Medicine & Surgery 7 (1): e587. doi:10.1002/ams2.587. ISSN 2052-8817. PMID 33173587.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Pisano, Michele; Zorcolo, Luigi; Merli, Cecilia; Cimbanassi, Stefania; Poiasina, Elia; Ceresoli, Marco; Agresta, Ferdinando; Allievi, Niccolò et al. (2018). "2017 WSES guidelines on colon and rectal cancer emergencies: obstruction and perforation". World Journal of Emergency Surgery 13: 36. doi:10.1186/s13017-018-0192-3. ISSN 1749-7922. PMID 30123315.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Nascimbeni, R.; Amato, A.; Cirocchi, R.; Serventi, A.; Laghi, A.; Bellini, M.; Tellan, G.; Zago, M. et al. (February 2021). "Management of perforated diverticulitis with generalized peritonitis. A multidisciplinary review and position paper". Techniques in Coloproctology 25 (2): 153–165. doi:10.1007/s10151-020-02346-y. ISSN 1128-045X. PMID 33155148.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Chung, Kin Tong; Shelat, Vishalkumar G. (2017-01-27). "Perforated peptic ulcer - an update". World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery 9 (1): 1–12. doi:10.4240/wjgs.v9.i1.1. ISSN 1948-9366. PMID 28138363.

- ↑ Smyth, Luke; Bendinelli, Cino; Lee, Nicholas; Reeds, Matthew G.; Loh, Eu Jhin; Amico, Francesco; Balogh, Zsolt J.; Di Saverio, Salomone et al. (2022-03-04). "WSES guidelines on blunt and penetrating bowel injury: diagnosis, investigations, and treatment". World Journal of Emergency Surgery 17 (1): 13. doi:10.1186/s13017-022-00418-y. ISSN 1749-7922. PMID 35246190.

- ↑ Bala, Miklosh; Kashuk, Jeffry; Moore, Ernest E.; Kluger, Yoram; Biffl, Walter; Gomes, Carlos Augusto; Ben-Ishay, Offir; Rubinstein, Chen et al. (December 2017). "Acute mesenteric ischemia: guidelines of the World Society of Emergency Surgery". World Journal of Emergency Surgery 12 (1): 38. doi:10.1186/s13017-017-0150-5. PMID 28794797.

- ↑ Fang, Alex H.; Chao, Wilson; Ecker, Melanie (2020-12-16). "Review of Colonic Anastomotic Leakage and Prevention Methods". Journal of Clinical Medicine 9 (12): 4061. doi:10.3390/jcm9124061. ISSN 2077-0383. PMID 33339209.

- ↑ Ds, Keller; K, Talboom; Cpm, van Helsdingen; R, Hompes (2021-11-23). "Treatment Modalities for Anastomotic Leakage in Rectal Cancer Surgery" (in en). Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery 34 (6): 431–438. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1736465. ISSN 1531-0043. PMID 34853566.

- ↑ Tansawet, Amarit; Numthavaj, Pawin; Techapongsatorn, Thawin; Techapongsatorn, Suphakarn; Attia, John; McKay, Gareth; Thakkinstian, Ammarin (December 2022). "Fascial Dehiscence and Incisional Hernia Prediction Models: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". World Journal of Surgery 46 (12): 2984–2995. doi:10.1007/s00268-022-06715-6. ISSN 1432-2323. PMID 36102959.

- ↑ van Rooijen, M. M. J.; Lange, J. F. (August 2018). "Preventing incisional hernia: closing the midline laparotomy". Techniques in Coloproctology 22 (8): 623–625. doi:10.1007/s10151-018-1833-y. ISSN 1128-045X. PMID 30094713.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Massironi, Sara; Cavalcoli, Federica; Rausa, Emanuele; Invernizzi, Pietro; Braga, Marco; Vecchi, Maurizio (March 2020). "Understanding short bowel syndrome: Current status and future perspectives". Digestive and Liver Disease 52 (3): 253–261. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2019.11.013. ISSN 1878-3562. PMID 31892505. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31892505.

- ↑ Billiauws, L.; Maggiori, L.; Joly, F.; Panis, Y. (September 2018). "Medical and surgical management of short bowel syndrome". Journal of Visceral Surgery 155 (4): 283–291. doi:10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2017.12.012. ISSN 1878-7886. PMID 30041905.

- ↑ Billiauws, Lore; Thomas, Muriel; Le Beyec-Le Bihan, Johanne; Joly, Francisca (2018-05-17). "Intestinal adaptation in short bowel syndrome. What is new?". Nutricion Hospitalaria 35 (3): 731–737. doi:10.20960/nh.1952. ISSN 1699-5198. PMID 29974785. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29974785.

External links

|