Physics:Degree of coherence

In quantum optics, correlation functions are used to characterize the statistical and coherence properties of an electromagnetic field. The degree of coherence is the normalized correlation of electric fields; in its simplest form, termed [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(1)} }[/math]. It is useful for quantifying the coherence between two electric fields, as measured in a Michelson or other linear optical interferometer. The correlation between pairs of fields, [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(2)} }[/math], typically is used to find the statistical character of intensity fluctuations. First order correlation is actually the amplitude-amplitude correlation and the second order correlation is the intensity-intensity correlation. It is also used to differentiate between states of light that require a quantum mechanical description and those for which classical fields are sufficient. Analogous considerations apply to any Bose field in subatomic physics, in particular to mesons (cf. Bose–Einstein correlations).

Degree of first-order coherence

The normalized first order correlation function is written as:[1]

- [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(1)}( \mathbf{r}_1, t_1;\mathbf{r}_2, t_2) = \frac{\left\langle E^*(\mathbf{r}_1, t_1) E(\mathbf{r}_2, t_2) \right\rangle} {\left[ \left\langle\left| E(\mathbf{r}_1, t_1) \right|^2 \right\rangle \left\langle \left| E(\mathbf{r}_2, t_2) \right|^2 \right\rangle \right]^\frac{1}{2}}, }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \langle \cdots \rangle }[/math] denotes a (statistical) ensemble average. For non-stationary states, such as pulses, the ensemble is made up of many pulses. When one deals with stationary states, where the statistical properties do not change with time, one can replace the ensemble average with a time average. If we restrict ourselves to plane parallel to each other waves then [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{r}=z }[/math].

In this case, the result for stationary states will not depend on [math]\displaystyle{ t_1 }[/math], but on the time delay [math]\displaystyle{ \tau=t_1-t_2 }[/math] (or [math]\displaystyle{ \tau=t_1-t_2=\frac{z_1-z_2}{c} }[/math] if [math]\displaystyle{ z_1 \ne z_2 }[/math]).

This allows us to write a simplified form

- [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(1)}( \tau)= \frac{\left \langle E^*(t)E(t+\tau) \right \rangle}{\left \langle\left | E(t)\right |^2 \right \rangle }, }[/math]

where we have now averaged over t.

Applications

In optical interferometers such as the Michelson interferometer, Mach–Zehnder interferometer, or Sagnac interferometer, one splits an electric field into two components, introduces a time delay to one of the components, and then recombines them. The intensity of resulting field is measured as a function of the time delay. In this specific case involving two equal input intensities, the visibility of the resulting interference pattern is given by:[2]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \nu &= \left| g^{(1)}(\tau) \right| \\ \nu &= \left| g^{(1)}(\mathbf{r}_1, t_1; \mathbf{r}_2, t_2) \right| \end{align} }[/math]

where the second expression involves combining two space-time points from a field. The visibility ranges from zero, for incoherent electric fields, to one, for coherent electric fields. Anything in between is described as partially coherent.

Generally, [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(1)}(0) = 1 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(1)}(\tau) = g^{(1)}(-\tau)^* }[/math].

Examples of g(1)

For light of a single frequency (of a point source):

- [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(1)}(\tau) = e^{-i\omega_0\tau} }[/math]

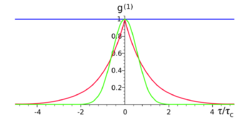

For Lorentzian chaotic light (e.g. collision broadened):

- [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(1)}(\tau) = e^{-i\omega_0\tau-\frac{|\tau|}{\tau_c}} }[/math]

For Gaussian chaotic light (e.g. Doppler broadened):

- [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(1)}(\tau) = e^{-i\omega_0\tau-\frac{\pi}{2}\left(\frac{\tau}{\tau_c}\right)^2} }[/math]

Here, [math]\displaystyle{ \omega_0 }[/math] is the central frequency of the light and [math]\displaystyle{ \tau_c }[/math] is the coherence time of the light.

Degree of second-order coherence

The normalised second order correlation function is written as:[1]

- [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(2)}( \mathbf{r}_1,t_1;\mathbf{r}_2,t_2) = \frac{\left \langle E^*(\mathbf{r}_1,t_1)E^*(\mathbf{r}_2,t_2)E(\mathbf{r}_1,t_1)E(\mathbf{r}_2,t_2) \right \rangle}{\left \langle\left | E(\mathbf{r}_1,t_1)\right |^2 \right \rangle \left \langle \left |E(\mathbf{r}_2,t_2)\right |^2 \right \rangle } }[/math]

Note that this is not a generalization of the first-order coherence

If the electric fields are considered classical, we can reorder them to express [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(2)} }[/math] in terms of intensities. A plane parallel wave in a stationary state will have

- [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(2)}(\tau)= \frac{\left \langle I(t)I(t + \tau) \right \rangle}{\left \langle I(t) \right \rangle^2 } }[/math]

The above expression is even, [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(2)}(\tau)= g^{(2)}(-\tau) }[/math]. For classical fields, one can apply the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality to the intensities in the above expression (since they are real numbers) to show that [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(2)}(\tau) \le g^{(2)}(0) }[/math]. The inequality [math]\displaystyle{ \left\langle I(t) I(t) \right\rangle - {\left\langle I(t) \right\rangle}^2 = \left\langle {\left[ I(t) - \left\langle I(t) \right\rangle \right]}^2 \right\rangle \geq 0 }[/math] shows that [math]\displaystyle{ 1 \le g^{(2)}(0) \le \infty }[/math]. Assuming independence of intensities when [math]\displaystyle{ \tau \to +\infty }[/math] leads to [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(2)}(+\infty) = 1 }[/math]. Nevertheless, the second-order coherence for an average over fringes of complementary interferometer outputs of a coherent state is only 0.5 (even though [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(2)} = 1 }[/math] for each output). And [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(2)} }[/math] (calculated from averages) can be reduced down to zero with a proper discriminating trigger level applied to the signal (within the range of coherence).

Examples of g(2)

- Chaotic light of all kinds: [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(2)}(\tau) = 1 + \left| g^{(1)}(\tau) \right|^2 }[/math].

Note the Hanbury Brown and Twiss effect uses this fact to find [math]\displaystyle{ \left| g^{(1)}(\tau) \right| }[/math] from a measurement of [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(2)}(\tau) }[/math].

- Light of a single frequency: [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(2)}(\tau) = 1 }[/math].

- In the case of photon antibunching, for [math]\displaystyle{ \tau = 0 }[/math] we have [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(2)}(0) = 0 }[/math] for a single photon source because

- [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(2)}(0)= \frac{\left\langle n(n - 1) \right\rangle}{\left\langle n \right\rangle^2}, }[/math]

- where [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] is the photon number observable.[3]

Degree of nth-order coherence

A generalization of the first-order coherence

- [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(n)}( \mathbf{r}_1,t_1;\mathbf{r}_2,t_2;\dots;\mathbf{r}_{2n},t_{2n})= \frac{\left \langle E^*(\mathbf{r}_1,t_1)E^*(\mathbf{r}_2,t_2)\cdots E^*(\mathbf{r}_n,t_n)E(\mathbf{r}_{n+1},t_{n+1})E(\mathbf{r}_{n+2},t_{n+2}) \dots E(\mathbf{r}_{2n},t_{2n}) \right \rangle}{\left [ \left \langle\left | E(\mathbf{r}_1,t_1)\right |^2 \right \rangle \left \langle \left |E(\mathbf{r}_2,t_2)\right |^2 \right \rangle\cdots\left \langle \left |E(\mathbf{r}_{2n},t_{2n})\right |^2 \right \rangle \right ]^{1/2}} }[/math]

A generalization of the second-order coherence

- [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(n)}( \mathbf{r}_1,t_1;\mathbf{r}_2,t_2;\dots;\mathbf{r}_n,t_n)= \frac{\left \langle E^*(\mathbf{r}_1,t_1)E^*(\mathbf{r}_2,t_2)\cdots E^*(\mathbf{r}_n,t_n)E(\mathbf{r}_1,t_1)E(\mathbf{r}_2,t_2)\cdots E(\mathbf{r}_n,t_n) \right \rangle}{\left \langle\left | E(\mathbf{r}_1,t_1)\right |^2 \right \rangle \left \langle \left |E(\mathbf{r}_2,t_2)\right |^2 \right \rangle\cdots \left \langle \left |E(\mathbf{r}_n,t_n)\right |^2 \right \rangle } }[/math]

or in intensities

- [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(n)}( \mathbf{r}_1,t_1;\mathbf{r}_2,t_2;\dots;\mathbf{r}_n,t_n)= \frac{\langle I(\mathbf{r}_1,t_1) I(\mathbf{r}_2,t_2)\cdots I(\mathbf{r}_n,t_n) \rangle}{\langle I(\mathbf{r}_1,t_1) \rangle \langle I(\mathbf{r}_2,t_2) \rangle \cdots \langle I(\mathbf{r}_n,t_n) \rangle } }[/math]

Examples of g(n)

Light of a single frequency:

- [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(n)}( \mathbf{r}_1,t_1;\mathbf{r}_2,t_2;\dots;\mathbf{r}_n,t_n)=1 }[/math]

Using the first definition: Chaotic light of all kinds: [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(n)}(\infty) = 0 }[/math]

Using the second definition: Chaotic light of all kinds: [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(n)}(\infty) = 1 }[/math] Chaotic light of all kinds: [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(n)}(0) = n! }[/math]

Generalization to quantum fields

The predictions of [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(n)} }[/math] for n > 1 change when the classical fields (complex numbers or c-numbers) are replaced with quantum fields (operators or q-numbers). In general, quantum fields do not necessarily commute, with the consequence that their order in the above expressions can not be simply interchanged.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} E^* &\rightarrow \hat{E}^- \\ E &\rightarrow \hat{E}^+. \end{align} }[/math]

With

- [math]\displaystyle{ \hat{E}^-= -i\left (\frac{\hbar\omega}{2\epsilon_0 V} \right )^\frac{1}{2}\hat{a}^\dagger e^{-i(kz-\omega t)} }[/math]

we get in the case of stationary light:

- [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(2)} = \frac{\left\langle \hat{a}^\dagger(t) \hat{a}^\dagger(t + \tau) \hat{a}(t + \tau) \hat{a}(t) \right\rangle}{\left\langle \hat{a}^\dagger(t) \hat{a}(t) \right\rangle^2} }[/math]

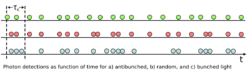

Photon bunching

Light is said to be bunched if [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(2)}(\tau) \lt g^{(2)}(0) }[/math] and antibunched if [math]\displaystyle{ g^{(2)}(\tau) \gt g^{(2)}(0) }[/math].

See also

- Bose–Einstein correlations

- Coherence theory

- Correlation and dependence

- Fourier transform spectroscopy

- Normally distributed and uncorrelated does not imply independent

- Optical autocorrelation

- Orders Of Coherence

- Van Cittert–Zernike theorem

- Interferometric visibility

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Marlan O. Scully; M. Suhail Zubairy (4 September 1997). Quantum Optics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 111ff. ISBN 978-1-139-64306-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=9lkgAwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ "Archived copy". http://www.colorado.edu/physics/phys4510/phys4510_fa05/Chapter8.pdf.

- ↑ SINGLE PHOTONS FOR QUANTUM INFORMATION PROCESSING - http://www.stanford.edu/group/yamamotogroup/Thesis/DFthesis.pdf (Archived copy: https://web.archive.org/web/20121023140645/http://www.stanford.edu/group/yamamotogroup/Thesis/DFthesis.pdf)

Suggested reading

- Loudon, Rodney, The Quantum Theory of Light (Oxford University Press, 2000), ISBN:0-19-850177-3