Physics:Critical dimension

In the renormalization group analysis of phase transitions in physics, a critical dimension is the dimensionality of space at which the character of the phase transition changes. Below the lower critical dimension there is no phase transition. Above the upper critical dimension the critical exponents of the theory become the same as that in mean field theory. An elegant criterion to obtain the critical dimension within mean field theory is due to V. Ginzburg.

Since the renormalization group sets up a relation between a phase transition and a quantum field theory, this has implications for the latter and for our larger understanding of renormalization in general. Above the upper critical dimension, the quantum field theory which belongs to the model of the phase transition is a free field theory. Below the lower critical dimension, there is no field theory corresponding to the model.

In the context of string theory the meaning is more restricted: the critical dimension is the dimension at which string theory is consistent assuming a constant dilaton background without additional confounding permutations from background radiation effects. The precise number may be determined by the required cancellation of conformal anomaly on the worldsheet; it is 26 for the bosonic string theory and 10 for superstring theory.

Upper critical dimension in field theory

Determining the upper critical dimension of a field theory is a matter of linear algebra. It is worthwhile to formalize the procedure because it yields the lowest-order approximation for scaling and essential input for the renormalization group. It also reveals conditions to have a critical model in the first place.

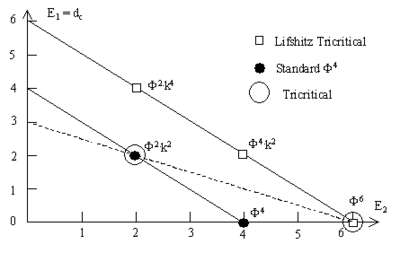

A Lagrangian may be written as a sum of terms, each consisting of an integral over a monomial of coordinates [math]\displaystyle{ x_i }[/math] and fields [math]\displaystyle{ \phi_i }[/math]. Examples are the standard [math]\displaystyle{ \phi^4 }[/math]-model and the isotropic Lifshitz tricritical point with Lagrangians

- [math]\displaystyle{ \displaystyle S =\int d^{d}x\left\{ \frac{1}{2}\left( \nabla \phi \right) ^{2}+u\phi^{4}\right\}, }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \displaystyle S_{L.T.P} =\int d^{d}x\left\{ \frac{1}{2}\left( \nabla ^{2}\phi \right) ^{2}+u\phi ^{3}\nabla ^{2}\phi +w\phi ^{6}\right\} , }[/math]

see also the figure on the right. This simple structure may be compatible with a scale invariance under a rescaling of the coordinates and fields with a factor [math]\displaystyle{ b }[/math] according to

- [math]\displaystyle{ \displaystyle x_{i}\rightarrow x_{i}b^{\left[ x_{i}\right]}, \phi _{i}\rightarrow \phi _{i}b^{\left[ \phi _{i}\right] }. }[/math]

Time is not singled out here — it is just another coordinate: if the Lagrangian contains a time variable then this variable is to be rescaled as [math]\displaystyle{ t\rarr tb^{-z} }[/math] with some constant exponent [math]\displaystyle{ z=-[t] }[/math]. The goal is to determine the exponent set [math]\displaystyle{ N=\{[x_i], [\phi_i]\} }[/math].

One exponent, say [math]\displaystyle{ [x_1] }[/math], may be chosen arbitrarily, for example [math]\displaystyle{ [x_1]=-1 }[/math]. In the language of dimensional analysis this means that the exponents [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math] count wave vector factors (a reciprocal length [math]\displaystyle{ k=1/L_1 }[/math]). Each monomial of the Lagrangian thus leads to a homogeneous linear equation [math]\displaystyle{ \sum E_{i,j}N_j=0 }[/math] for the exponents [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math]. If there are [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] (inequivalent) coordinates and fields in the Lagrangian, then [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] such equations constitute a square matrix. If this matrix were invertible then there only would be the trivial solution [math]\displaystyle{ N=0 }[/math].

The condition [math]\displaystyle{ \det(E_{i,j})=0 }[/math] for a nontrivial solution gives an equation between the space dimensions, and this determines the upper critical dimension [math]\displaystyle{ d_u }[/math] (provided there is only one variable dimension [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math] in the Lagrangian). A redefinition of the coordinates and fields now shows that determining the scaling exponents [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math] is equivalent to a dimensional analysis with respect to the wavevector [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math], with all coupling constants occurring in the Lagrangian rendered dimensionless. Dimensionless coupling constants are the technical hallmark for the upper critical dimension.

Naive scaling at the level of the Lagrangian does not directly correspond to physical scaling because a cutoff is required to give a meaning to the field theory and the path integral. Changing the length scale also changes the number of degrees of freedom. This complication is taken into account by the renormalization group. The main result at the upper critical dimension is that scale invariance remains valid for large factors [math]\displaystyle{ b }[/math], but with additional [math]\displaystyle{ ln(b) }[/math] factors in the scaling of the coordinates and fields.

What happens below or above [math]\displaystyle{ d_u }[/math] depends on whether one is interested in long distances (statistical field theory) or short distances (quantum field theory). Quantum field theories are trivial (convergent) below [math]\displaystyle{ d_u }[/math] and not renormalizable above [math]\displaystyle{ d_u }[/math].[1] Statistical field theories are trivial (convergent) above [math]\displaystyle{ d_u }[/math] and renormalizable below [math]\displaystyle{ d_u }[/math]. In the latter case there arise "anomalous" contributions to the naive scaling exponents [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math]. These anomalous contributions to the effective critical exponents vanish at the upper critical dimension.

It is instructive to see how the scale invariance at the upper critical dimension becomes a scale invariance below this dimension. For small external wave vectors the vertex functions [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma }[/math] acquire additional exponents, for example [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma_2(k)\thicksim k^{2-\eta(d)} }[/math]. If these exponents are inserted into a matrix [math]\displaystyle{ A(d) }[/math] (which only has values in the first column) the condition for scale invariance becomes [math]\displaystyle{ \det(E+A(d))=0 }[/math]. This equation only can be satisfied if the anomalous exponents of the vertex functions cooperate in some way. In fact, the vertex functions depend on each other hierarchically. One way to express this interdependence are the Dyson–Schwinger equations.

Naive scaling at [math]\displaystyle{ d_u }[/math] thus is important as zeroth order approximation. Naive scaling at the upper critical dimension also classifies terms of the Lagrangian as relevant, irrelevant or marginal. A Lagrangian is compatible with scaling if the [math]\displaystyle{ x_i }[/math]- and [math]\displaystyle{ \phi_i }[/math] -exponents [math]\displaystyle{ E_{i,j} }[/math] lie on a hyperplane, for examples see the figure above. [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math] is a normal vector of this hyperplane.

Lower critical dimension

The lower critical dimension [math]\displaystyle{ d_L }[/math] of a phase transition of a given universality class is the last dimension for which this phase transition does not occur if the dimension is increased starting with [math]\displaystyle{ d=1 }[/math].

Thermodynamic stability of an ordered phase depends on entropy and energy. Quantitatively this depends on the type of domain walls and their fluctuation modes. There appears to be no generic formal way for deriving the lower critical dimension of a field theory. Lower bounds may be derived with statistical mechanics arguments.

Consider first a one-dimensional system with short range interactions. Creating a domain wall requires a fixed energy amount [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon }[/math]. Extracting this energy from other degrees of freedom decreases entropy by [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta S=-\epsilon/T }[/math]. This entropy change must be compared with the entropy of the domain wall itself.[2] In a system of length [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math] there are [math]\displaystyle{ L/a }[/math] positions for the domain wall, leading (according to Boltzmann's principle) to an entropy gain [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta S=k_B \log(L/a) }[/math]. For nonzero temperature [math]\displaystyle{ T }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ L }[/math] large enough the entropy gain always dominates, and thus there is no phase transition in one-dimensional systems with short-range interactions at [math]\displaystyle{ T \gt 0 }[/math]. Space dimension [math]\displaystyle{ d_1=1 }[/math] thus is a lower bound for the lower critical dimension of such systems.

A stronger lower bound [math]\displaystyle{ d_L=2 }[/math] can be derived with the help of similar arguments for systems with short range interactions and an order parameter with a continuous symmetry. In this case the Mermin–Wagner Theorem states that the order parameter expectation value vanishes in [math]\displaystyle{ d=2 }[/math] at [math]\displaystyle{ T \gt 0 }[/math], and there thus is no phase transition of the usual type at [math]\displaystyle{ d_L=2 }[/math] and below.

For systems with quenched disorder a criterion given by Imry and Ma[3] might be relevant. These authors used the criterion to determine the lower critical dimension of random field magnets.

References

- ↑ Zinn-Justin, Jean (1996). Quantum field theory and critical phenomena. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-851882-X.

- ↑ Pitaevskii, L. P.; Landau, L. D.; Lifshitz, E. M.; Sykes, J. B.; Kearsley, M. W.; Lifshitz, E. M. (1991). Statistical physics. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-3372-7.

- ↑ Imry, Y.; S. K. Ma (1975). "Random-Field Instability of the Ordered State of Continuous Symmetry". Phys. Rev. Lett. 35 (21): 1399–1401. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.35.1399. Bibcode: 1975PhRvL..35.1399I.

External links

|