Plane of rotation

In geometry, a plane of rotation is an abstract object used to describe or visualize rotations in space.

The main use for planes of rotation is in describing more complex rotations in four-dimensional space and higher dimensions, where they can be used to break down the rotations into simpler parts. This can be done using geometric algebra, with the planes of rotations associated with simple bivectors in the algebra.[1]

Planes of rotation are not used much in two and three dimensions, as in two dimensions there is only one plane (so, identifying the plane of rotation is trivial and rarely done), while in three dimensions the axis of rotation serves the same purpose and is the more established approach.

Mathematically such planes can be described in a number of ways. They can be described in terms of planes and angles of rotation. They can be associated with bivectors from geometric algebra. They are related to the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of a rotation matrix. And in particular dimensions they are related to other algebraic and geometric properties, which can then be generalised to other dimensions.

Definitions

Plane

For this article, all planes are planes through the origin, that is they contain the zero vector. Such a plane in n-dimensional space is a two-dimensional linear subspace of the space. It is completely specified by any two non-zero and non-parallel vectors that lie in the plane, that is by any two vectors a and b, such that

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{a} \wedge \mathbf{b} \ne 0, }[/math]

where ∧ is the exterior product from exterior algebra or geometric algebra (in three dimensions the cross product can be used). More precisely, the quantity a ∧ b is the bivector associated with the plane specified by a and b, and has magnitude |a| |b| sin φ, where φ is the angle between the vectors; hence the requirement that the vectors be nonzero and nonparallel.[2]

If the bivector a ∧ b is written B, then the condition that a point lies on the plane associated with B is simply[3]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{x} \wedge \mathbf{B} = 0. }[/math]

This is true in all dimensions, and can be taken as the definition on the plane. In particular, from the properties of the exterior product it is satisfied by both a and b, and so by any vector of the form

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{c} = \lambda\mathbf{a} + \mu\mathbf{b}, }[/math]

with λ and μ real numbers. As λ and μ range over all real numbers, c ranges over the whole plane, so this can be taken as another definition of the plane.

Plane of rotation

A plane of rotation for a particular rotation is a plane that is mapped to itself by the rotation. The plane is not fixed, but all vectors in the plane are mapped to other vectors in the same plane by the rotation. This transformation of the plane to itself is always a rotation about the origin, through an angle which is the angle of rotation for the plane.

Every rotation except for the identity rotation (with matrix the identity matrix) has at least one plane of rotation, and up to

- [math]\displaystyle{ \left\lfloor \frac{n}{2} \right\rfloor }[/math]

planes of rotation, where n is the dimension. The maximum number of planes up to eight dimensions is shown in this table:

Dimension 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Number of planes 1 1 2 2 3 3 4

When a rotation has multiple planes of rotation they are always orthogonal to each other, with only the origin in common. This is a stronger condition than to say the planes are at right angles; it instead means that the planes have no nonzero vectors in common, and that every vector in one plane is orthogonal to every vector in the other plane. This can only happen in four or more dimensions. In two dimensions there is only one plane, while in three dimensions all planes have at least one nonzero vector in common, along their line of intersection.[4]

In more than three dimensions planes of rotation are not always unique. For example the negative of the identity matrix in four dimensions (the central inversion),

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{pmatrix} -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 \end{pmatrix}, }[/math]

describes a rotation in four dimensions in which every plane through the origin is a plane of rotation through an angle π, so any pair of orthogonal planes generates the rotation. But for a general rotation it is at least theoretically possible to identify a unique set of orthogonal planes, in each of which points are rotated through an angle, so the set of planes and angles fully characterise the rotation.[5]

Two dimensions

In two-dimensional space there is only one plane of rotation, the plane of the space itself. In a Cartesian coordinate system it is the Cartesian plane, in complex numbers it is the complex plane. Any rotation therefore is of the whole plane, i.e. of the space, keeping only the origin fixed. It is specified completely by the signed angle of rotation, in the range for example −π to π. So if the angle is θ the rotation in the complex plane is given by Euler's formula:

- [math]\displaystyle{ e^{i\theta} = \cos{\theta} + i\sin{\theta},\, }[/math]

while the rotation in a Cartesian plane is given by the 2 × 2 rotation matrix:[6]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{pmatrix} \cos \theta & -\sin \theta \\ \sin \theta & \cos \theta \end{pmatrix}. }[/math]

Three dimensions

In three-dimensional space there are an infinite number of planes of rotation, only one of which is involved in any given rotation. That is, for a general rotation there is precisely one plane which is associated with it or which the rotation takes place in. The only exception is the trivial rotation, corresponding to the identity matrix, in which no rotation takes place.

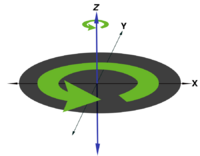

In any rotation in three dimensions there is always a fixed axis, the axis of rotation. The rotation can be described by giving this axis, with the angle through which the rotation turns about it; this is the axis angle representation of a rotation. The plane of rotation is the plane orthogonal to this axis, so the axis is a surface normal of the plane. The rotation then rotates this plane through the same angle as it rotates around the axis, that is everything in the plane rotates by the same angle about the origin.

One example is shown in the diagram, where the rotation takes place about the z-axis. The plane of rotation is the xy-plane, so everything in that plane it kept in the plane by the rotation. This could be described by a matrix like the following, with the rotation being through an angle θ (about the axis or in the plane):

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{pmatrix} \cos \theta & -\sin \theta & 0 \\ \sin \theta & \cos \theta & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix}. }[/math]

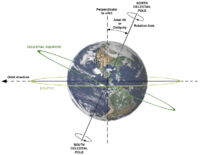

Another example is the Earth's rotation. The axis of rotation is the line joining the North Pole and South Pole and the plane of rotation is the plane through the equator between the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. Other examples include mechanical devices like a gyroscope or flywheel which store rotational energy in mass usually along the plane of rotation.

In any three dimensional rotation the plane of rotation is uniquely defined. Together with the angle of rotation it fully describes the rotation. Or in a continuously rotating object the rotational properties such as the rate of rotation can be described in terms of the plane of rotation. It is perpendicular to, and so is defined by and defines, an axis of rotation, so any description of a rotation in terms of a plane of rotation can be described in terms of an axis of rotation, and vice versa. But unlike the axis of rotation the plane generalises into other, in particular higher, dimensions.[7]

Four dimensions

A general rotation in four-dimensional space has only one fixed point, the origin. Therefore an axis of rotation cannot be used in four dimensions. But planes of rotation can be used, and each non-trivial rotation in four dimensions has one or two planes of rotation.

Simple rotations

A rotation with only one plane of rotation is a simple rotation. In a simple rotation there is a fixed plane, and rotation can be said to take place about this plane, so points as they rotate do not change their distance from this plane. The plane of rotation is orthogonal to this plane, and the rotation can be said to take place in this plane.

For example the following matrix fixes the xy-plane: points in that plane and only in that plane are unchanged. The plane of rotation is the zw-plane, points in this plane are rotated through an angle θ. A general point rotates only in the zw-plane, that is it rotates around the xy-plane by changing only its z and w coordinates.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \cos \theta & -\sin \theta \\ 0 & 0 & \sin \theta & \cos \theta \end{pmatrix} }[/math]

In two and three dimensions all rotations are simple, in that they have only one plane of rotation. Only in four and more dimensions are there rotations that are not simple rotations. In particular in four dimensions there are also double and isoclinic rotations.

Double rotations

In a double rotation there are two planes of rotation, no fixed planes, and the only fixed point is the origin. The rotation can be said to take place in both planes of rotation, as points in them are rotated within the planes. These planes are orthogonal, that is they have no vectors in common so every vector in one plane is at right angles to every vector in the other plane. The two rotation planes span four-dimensional space, so every point in the space can be specified by two points, one on each of the planes.

A double rotation has two angles of rotation, one for each plane of rotation. The rotation is specified by giving the two planes and two non-zero angles, α and β (if either angle is zero the rotation is simple). Points in the first plane rotate through α, while points in the second plane rotate through β. All other points rotate through an angle between α and β, so in a sense they together determine the amount of rotation. For a general double rotation the planes of rotation and angles are unique, and given a general rotation they can be calculated. For example a rotation of α in the xy-plane and β in the zw-plane is given by the matrix

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{pmatrix} \cos \alpha & -\sin \alpha & 0 & 0 \\ \sin \alpha & \cos \alpha & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & \cos \beta & -\sin \beta \\ 0 & 0 & \sin \beta & \cos \beta \end{pmatrix}. }[/math]

Isoclinic rotations

A special case of the double rotation is when the angles are equal, that is if α = β ≠ 0. This is called an isoclinic rotation, and it differs from a general double rotation in a number of ways. For example in an isoclinic rotation, all non-zero points rotate through the same angle, α. Most importantly the planes of rotation are not uniquely identified. There are instead an infinite number of pairs of orthogonal planes that can be treated as planes of rotation. For example any point can be taken, and the plane it rotates in together with the plane orthogonal to it can be used as two planes of rotation.[8]

Higher dimensions

As already noted the maximum number of planes of rotation in n dimensions is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \left\lfloor \frac{n}{2} \right\rfloor, }[/math]

so the complexity quickly increases with more than four dimensions and categorising rotations as above becomes too complex to be practical, but some observations can be made.

Simple rotations can be identified in all dimensions, as rotations with just one plane of rotation. A simple rotation in n dimensions takes place about (that is at a fixed distance from) an (n − 2)-dimensional subspace orthogonal to the plane of rotation.

A general rotation is not simple, and has the maximum number of planes of rotation as given above. In the general case the angles of rotations in these planes are distinct and the planes are uniquely defined. If any of the angles are the same then the planes are not unique, as in four dimensions with an isoclinic rotation.

In even dimensions (n = 2, 4, 6...) there are up to n/2 planes of rotation span the space, so a general rotation rotates all points except the origin which is the only fixed point. In odd dimensions (n = 3, 5, 7, ...) there are n − 1/2 planes and angles of rotation, the same as the even dimension one lower. These do not span the space, but leave a line which does not rotate – like the axis of rotation in three dimensions, except rotations do not take place about this line but in multiple planes orthogonal to it.[1]

Mathematical properties

The examples given above were chosen to be clear and simple examples of rotations, with planes generally parallel to the coordinate axes in three and four dimensions. But this is not generally the case: planes are not usually parallel to the axes, and the matrices cannot simply be written down. In all dimensions the rotations are fully described by the planes of rotation and their associated angles, so it is useful to be able to determine them, or at least find ways to describe them mathematically.

Reflections

Every simple rotation can be generated by two reflections. Reflections can be specified in n dimensions by giving an (n − 1)-dimensional subspace to reflect in, so a two-dimensional reflection is in a line, a three-dimensional reflection is in a plane, and so on. But this becomes increasingly difficult to apply in higher dimensions, so it is better to use vectors instead, as follows.

A reflection in n dimensions is specified by a vector perpendicular to the (n − 1)-dimensional subspace. To generate simple rotations only reflections that fix the origin are needed, so the vector does not have a position, just direction. It does also not matter which way it is facing: it can be replaced with its negative without changing the result. Similarly unit vectors can be used to simplify the calculations.

So the reflection in a (n − 1)-dimensional space is given by the unit vector perpendicular to it, m, thus:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{x}' = -\mathbf{mxm} \, }[/math]

where the product is the geometric product from geometric algebra.

If x′ is reflected in another, distinct, (n − 1)-dimensional space, described by a unit vector n perpendicular to it, the result is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{x}'' = -\mathbf{nx}'\mathbf{n} = -\mathbf{n}(-\mathbf{mxm})\mathbf{n} = \mathbf{nmxmn} }[/math]

This is a simple rotation in n dimensions, through twice the angle between the subspaces, which is also the angle between the vectors m and n. It can be checked using geometric algebra that this is a rotation, and that it rotates all vectors as expected.

The quantity mn is a rotor, and nm is its inverse as

- [math]\displaystyle{ (\mathbf{mn})(\mathbf{nm}) = \mathbf{mnnm} = \mathbf{mm} = 1 }[/math]

So the rotation can be written

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{x}'' = R\mathbf{x}R^{-1} }[/math]

where R = mn is the rotor.

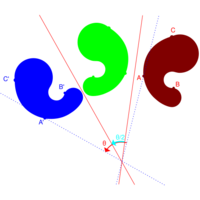

The plane of rotation is the plane containing m and n, which must be distinct otherwise the reflections are the same and no rotation takes place. As either vector can be replaced by its negative the angle between them can always be acute, or at most π/2. The rotation is through twice the angle between the vectors, up to π or a half-turn. The sense of the rotation is to rotate from m towards n: the geometric product is not commutative so the product nm is the inverse rotation, with sense from n to m.

Conversely all simple rotations can be generated this way, with two reflections, by two unit vectors in the plane of rotation separated by half the desired angle of rotation. These can be composed to produce more general rotations, using up to n reflections if the dimension n is even, n − 2 if n is odd, by choosing pairs of reflections given by two vectors in each plane of rotation.[9][10]

Bivectors

Bivectors are quantities from geometric algebra, clifford algebra and the exterior algebra, which generalise the idea of vectors into two dimensions. As vectors are to lines, so are bivectors to planes. So every plane (in any dimension) can be associated with a bivector, and every simple bivector is associated with a plane. This makes them a good fit for describing planes of rotation.

Every rotation plane in a rotation has a simple bivector associated with it. This is parallel to the plane and has magnitude equal to the angle of rotation in the plane. These bivectors are summed to produce a single, generally non-simple, bivector for the whole rotation. This can generate a rotor through the exponential map, which can be used to rotate an object.

Bivectors are related to rotors through the exponential map (which applied to bivectors generates rotors and rotations using De Moivre's formula). In particular given any bivector B the rotor associated with it is

- [math]\displaystyle{ R_{\mathbf{B}} = e^{\frac{\mathbf{B}}{2}}. }[/math]

This is a simple rotation if the bivector is simple, a more general rotation otherwise. When squared,

- [math]\displaystyle{ {R_{\mathbf{B}}}^2 = e^{\frac{\mathbf{B}}{2}}e^{\frac{\mathbf{B}}{2}} = e^{\mathbf{B}}, }[/math]

it gives a rotor that rotates through twice the angle. If B is simple then this is the same rotation as is generated by two reflections, as the product mn gives a rotation through twice the angle between the vectors. These can be equated,

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{mn} = e^{\mathbf{B}}, }[/math]

from which it follows that the bivector associated with the plane of rotation containing m and n that rotates m to n is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{B} = \log(\mathbf{mn}). }[/math]

This is a simple bivector, associated with the simple rotation described. More general rotations in four or more dimensions are associated with sums of simple bivectors, one for each plane of rotation, calculated as above.

Examples include the two rotations in four dimensions given above. The simple rotation in the zw-plane by an angle θ has bivector e34θ, a simple bivector. The double rotation by α and β in the xy-plane and zw-planes has bivector e12α + e34β, the sum of two simple bivectors e12α and e34β which are parallel to the two planes of rotation and have magnitudes equal to the angles of rotation.

Given a rotor the bivector associated with it can be recovered by taking the logarithm of the rotor, which can then be split into simple bivectors to determine the planes of rotation, although in practice for all but the simplest of cases this may be impractical. But given the simple bivectors geometric algebra is a useful tool for studying planes of rotation using algebra like the above.[1][11]

Eigenvalues and eigenplanes

The planes of rotations for a particular rotation using the eigenvalues. Given a general rotation matrix in n dimensions its characteristic equation has either one (in odd dimensions) or zero (in even dimensions) real roots. The other roots are in complex conjugate pairs, exactly

- [math]\displaystyle{ \left\lfloor \frac{n}{2} \right\rfloor, }[/math]

such pairs. These correspond to the planes of rotation, the eigenplanes of the matrix, which can be calculated using algebraic techniques. In addition arguments of the complex roots are the magnitudes of the bivectors associated with the planes of rotations. The form of the characteristic equation is related to the planes, making it possible to relate its algebraic properties like repeated roots to the bivectors, where repeated bivector magnitudes have particular geometric interpretations.[1][12]

See also

- Charts on SO(3)

- Givens rotation

- Quaternions

- Rotation group SO(3)

- Rotations in 4-dimensional Euclidean space

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Lounesto (2001) pp. 222–223

- ↑ Lounesto (2001) p. 38

- ↑ Hestenes (1999) p. 48

- ↑ Lounesto (2001) p. 222

- ↑ Lounesto (2001) p.87

- ↑ Lounesto (2001) pp.27–28

- ↑ Hestenes (1999) pp 280–284

- ↑ Lounesto (2001) pp. 83–89

- ↑ Lounesto (2001) p. 57–58

- ↑ Hestenes (1999) p. 278–280

- ↑ Dorst, Doran, Lasenby (2002) pp. 79–89

- ↑ Dorst, Doran, Lasenby (2002) pp. 145–154

References

- Hestenes, David (1999). New Foundations for Classical Mechanics (2nd ed.). Kluwer. ISBN 0-7923-5302-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=AlvTCEzSI5wC.

- Lounesto, Pertti (2001). Clifford algebras and spinors. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00551-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=kOsybQWDK4oC.

- Dorst, Leo; Doran, Chris; Lasenby, Joan (2002). Applications of geometric algebra in computer science and engineering. Birkhäuser. ISBN 0-8176-4267-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=NpJRkQfgtwUC.

|