Verma modules, named after Daya-Nand Verma, are objects in the representation theory of Lie algebras, a branch of mathematics.

Verma modules can be used in the classification of irreducible representations of a complex semisimple Lie algebra. Specifically, although Verma modules themselves are infinite dimensional, quotients of them can be used to construct finite-dimensional representations with highest weight , where is dominant and integral.[1] Their homomorphisms correspond to invariant differential operators over flag manifolds.

Informal construction

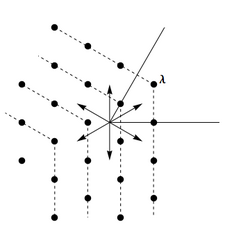

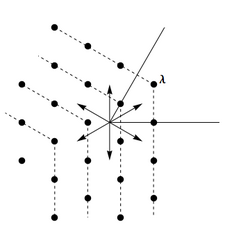

Weights of Verma module for

with highest weight

We can explain the idea of a Verma module as follows.[2] Let be a semisimple Lie algebra (over , for simplicity). Let be a fixed Cartan subalgebra of and let be the associated root system. Let be a fixed set of positive roots. For each , choose a nonzero element for the corresponding root space and a nonzero element in the root space . We think of the 's as "raising operators" and the 's as "lowering operators."

Now let be an arbitrary linear functional, not necessarily dominant or integral. Our goal is to construct a representation of with highest weight that is generated by a single nonzero vector with weight . The Verma module is one particular such highest-weight module, one that is maximal in the sense that every other highest-weight module with highest weight is a quotient of the Verma module. It will turn out that Verma modules are always infinite dimensional; if is dominant integral, however, one can construct a finite-dimensional quotient module of the Verma module. Thus, Verma modules play an important role in the classification of finite-dimensional representations of . Specifically, they are an important tool in the hard part of the theorem of the highest weight, namely showing that every dominant integral element actually arises as the highest weight of a finite-dimensional irreducible representation of .

We now attempt to understand intuitively what the Verma module with highest weight should look like. Since is to be a highest weight vector with weight , we certainly want

and

- .

Then should be spanned by elements obtained by lowering by the action of the 's:

- .

We now impose only those relations among vectors of the above form required by the commutation relations among the 's. In particular, the Verma module is always infinite-dimensional. The weights of the Verma module with highest weight will consist of all elements that can be obtained from by subtracting integer combinations of positive roots. The figure shows the weights of a Verma module for .

A simple re-ordering argument shows that there is only one possible way the full Lie algebra can act on this space. Specifically, if is any element of , then by the easy part of the Poincaré–Birkhoff–Witt theorem, we can rewrite

as a linear combination of products of Lie algebra elements with the raising operators acting first, the elements of the Cartan subalgebra, and last the lowering operators . Applying this sum of terms to , any term with a raising operator is zero, any factors in the Cartan act as scalars, and thus we end up with an element of the original form.

To understand the structure of the Verma module a bit better, we may choose an ordering of the positive roots as and we denote the corresponding lowering operators by . Then by a simple re-ordering argument, every element of the above form can be rewritten as a linear combination of elements with the 's in a specific order:

- ,

where the 's are non-negative integers. Actually, it turns out that such vectors form a basis for the Verma module.

Although this description of the Verma module gives an intuitive idea of what looks like, it still remains to give a rigorous construction of it. In any case, the Verma module gives—for any , not necessarily dominant or integral—a representation with highest weight . The price we pay for this relatively simple construction is that is always infinite dimensional. In the case where is dominant and integral, one can construct a finite-dimensional, irreducible quotient of the Verma module.[3]

The case of sl(2; C)

Let be the usual basis for :

with the Cartan subalgebra being the span of . Let be defined by for an arbitrary complex number . Then the Verma module with highest weight is spanned by linearly independent vectors and the action of the basis elements is as follows:[4]

- .

(This means in particular that and that .) These formulas are motivated by the way the basis elements act in the finite-dimensional representations of , except that we no longer require that the "chain" of eigenvectors for has to terminate.

In this construction, is an arbitrary complex number, not necessarily real or positive or an integer. Nevertheless, the case where is a non-negative integer is special. In that case, the span of the vectors is easily seen to be invariant—because . The quotient module is then the finite-dimensional irreducible representation of of dimension

Definition of Verma modules

There are two standard constructions of the Verma module, both of which involve the concept of universal enveloping algebra. We continue the notation of the previous section: is a complex semisimple Lie algebra, is a fixed Cartan subalgebra, is the associated root system with a fixed set of positive roots. For each , we choose nonzero elements and .

As a quotient of the enveloping algebra

The first construction[5] of the Verma module is a quotient of the universal enveloping algebra of . Since the Verma module is supposed to be a -module, it will also be a -module, by the universal property of the enveloping algebra. Thus, if we have a Verma module with highest weight vector , there will be a linear map from into given by

- .

Since is supposed to be generated by , the map should be surjective. Since is supposed to be a highest weight vector, the kernel of should include all the root vectors for in . Since, also, is supposed to be a weight vector with weight , the kernel of should include all vectors of the form

- .

Finally, the kernel of should be a left ideal in ; after all, if then for all .

The previous discussion motivates the following construction of Verma module. We define as the quotient vector space

- ,

where is the left ideal generated by all elements of the form

and

- .

Because is a left ideal, the natural left action of on itself carries over to the quotient. Thus, is a -module and therefore also a -module.

By extension of scalars

The "extension of scalars" procedure is a method for changing a left module over one algebra (not necessarily commutative) into a left module over a larger algebra that contains as a subalgebra. We can think of as a right -module, where acts on by multiplication on the right. Since is a left -module and is a right -module, we can form the tensor product of the two over the algebra :

- .

Now, since is a left -module over itself, the above tensor product carries a left module structure over the larger algebra , uniquely determined by the requirement that

for all and in . Thus, starting from the left -module , we have produced a left -module .

We now apply this construction in the setting of a semisimple Lie algebra. We let be the subalgebra of spanned by and the root vectors with . (Thus, is a "Borel subalgebra" of .) We can form a left module over the universal enveloping algebra as follows:

- is the one-dimensional vector space spanned by a single vector together with a -module structure such that acts as multiplication by and the positive root spaces act trivially:

- .

The motivation for this formula is that it describes how is supposed to act on the highest weight vector in a Verma module.

Now, it follows from the Poincaré–Birkhoff–Witt theorem that is a subalgebra of . Thus, we may apply the extension of scalars technique to convert from a left -module into a left -module as follow:

- .

Since is a left -module, it is, in particular, a module (representation) for .

The structure of the Verma module

Whichever construction of the Verma module is used, one has to prove that it is nontrivial, i.e., not the zero module. Actually, it is possible to use the Poincaré–Birkhoff–Witt theorem to show that the underlying vector space of is isomorphic to

where is the Lie subalgebra generated by the negative root spaces of (that is, the 's).[6]

Basic properties

Verma modules, considered as -modules, are highest weight modules, i.e. they are generated by a highest weight vector. This highest weight vector is (the first is the unit in and the second is

the unit in the field , considered as the -module

) and it has weight .

Multiplicities

Verma modules are weight modules, i.e. is a direct sum of all its weight spaces. Each weight space in is finite-dimensional and the dimension of the -weight space is the number of ways of expressing as a sum of positive roots (this is closely related to the so-called Kostant partition function). This assertion follows from the earlier claim that the Verma module is isomorphic as a vector space to , along with the Poincaré–Birkhoff–Witt theorem for .

Universal property

Verma modules have a very important property: If is any representation generated by a highest weight vector of weight , there is a surjective -homomorphism That is, all representations with highest weight that are generated by the highest weight vector (so called highest weight modules) are quotients of

Irreducible quotient module

contains a unique maximal submodule, and its quotient is the unique (up to isomorphism) irreducible representation with highest weight [7] If the highest weight is dominant and integral, one then proves that this irreducible quotient is actually finite dimensional.[8]

As an example, consider the case discussed above. If the highest weight is "dominant integral"—meaning simply that it is a non-negative integer—then and the span of the elements is invariant. The quotient representation is then irreducible with dimension . The quotient representation is spanned by linearly independent vectors . The action of is the same as in the Verma module, except that in the quotient, as compared to in the Verma module.

The Verma module itself is irreducible if and only if is antidominant.[9] Consequently, when is integral, is irreducible if and only if none of the coordinates of in the basis of fundamental weights is from the set , while in general, this condition is necessary but insufficient for to be irreducible.

Other properties

The Verma module is called regular, if its highest weight λ is on the affine Weyl orbit of a dominant weight . In other word, there exist an element w of the Weyl group W such that

where is the affine action of the Weyl group.

The Verma module is called singular, if there is no dominant weight on the affine orbit of λ. In this case, there exists a weight so that is on the wall of the fundamental Weyl chamber (δ is the sum of all fundamental weights).

Homomorphisms of Verma modules

For any two weights a non-trivial homomorphism

may exist only if and are linked with an affine action of the Weyl group of the Lie algebra . This follows easily from the Harish-Chandra theorem on infinitesimal central characters.

Each homomorphism of Verma modules is injective and the dimension

for any . So, there exists a nonzero if and only if is isomorphic to a (unique) submodule of .

The full classification of Verma module homomorphisms was done by Bernstein–Gelfand–Gelfand[10] and Verma[11] and can be summed up in the following statement:

There exists a nonzero homomorphism if and only if there exists

a sequence of weights

such that for some positive roots (and is the corresponding root reflection and is the sum of all fundamental weights) and for each is a natural number ( is the coroot associated to the root ).

If the Verma modules and are regular, then there exists a unique dominant weight and unique elements w, w′ of the Weyl group W such that

and

where is the affine action of the Weyl group. If the weights are further integral, then there exists a nonzero homomorphism

if and only if

in the Bruhat ordering of the Weyl group.

Jordan–Hölder series

Let

be a sequence of -modules so that the quotient B/A is irreducible with highest weight μ. Then there exists a nonzero homomorphism .

An easy consequence of this is, that for any highest weight modules such that

there exists a nonzero homomorphism .

Bernstein–Gelfand–Gelfand resolution

Let be a finite-dimensional irreducible representation of the Lie algebra with highest weight λ. We know from the section about homomorphisms of Verma modules that there exists a homomorphism

if and only if

in the Bruhat ordering of the Weyl group. The following theorem describes a resolution of in terms of Verma modules (it was proved by Bernstein–Gelfand–Gelfand in 1975[12]) :

There exists an exact sequence of -homomorphisms

where n is the length of the largest element of the Weyl group.

A similar resolution exists for generalized Verma modules as well. It is denoted shortly as the BGG resolution.

See also

Notes

- ↑ E.g., Hall 2015 Chapter 9

- ↑ Hall 2015 Section 9.2

- ↑ Hall 2015 Sections 9.6 and 9.7

- ↑ Hall 2015 Sections 9.2

- ↑ Hall 2015 Section 9.5

- ↑ Hall 2015 Theorem 9.14

- ↑ Hall 2015 Section 9.6

- ↑ Hall 2015 Section 9.7

- ↑ Humphreys, James (2008-07-22) (in en). Representations of Semisimple Lie Algebras in the BGG Category 𝒪. Graduate Studies in Mathematics. 94. American Mathematical Society. doi:10.1090/gsm/094. ISBN 978-0-8218-4678-0. http://www.ams.org/gsm/094.

- ↑ Bernstein I.N., Gelfand I.M., Gelfand S.I., Structure of Representations that are generated by vectors of highest weight, Functional. Anal. Appl. 5 (1971)

- ↑ Verma N., Structure of certain induced representations of complex semisimple Lie algebras, Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 74 (1968)

- ↑ Bernstein I. N., Gelfand I. M., Gelfand S. I., Differential Operators on the Base Affine Space and a Study of g-Modules, Lie Groups and Their Representations, I. M. Gelfand, Ed., Adam Hilger, London, 1975.

References

- Bäuerle, G.G.A; de Kerf, E.A.; ten Kroode, A.P.E. (1997). Finite and infinite dimensional Lie algebras and their application in physics. Studies in mathematical physics. 7. North-Holland. Chapter 20. ISBN 978-0-444-82836-1. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/bookseries/09258582.

- Carter, R. (2005), Lie Algebras of Finite and Affine Type, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-85138-1 .

- Dixmier, J. (1977), Enveloping Algebras, Amsterdam, New York, Oxford: North-Holland, ISBN 978-0-444-11077-0 .

- Hall, Brian C. (2015), Lie Groups, Lie Algebras, and Representations: An Elementary Introduction, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 222 (2nd ed.), Springer, ISBN 978-3319134666

- Humphreys, J. (1980), Introduction to Lie Algebras and Representation Theory, Springer Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-90052-8 .

- Knapp, A. W. (2002), Lie Groups Beyond an introduction (2nd ed.), Birkhäuser, p. 285, ISBN 978-0-8176-3926-6 .

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "BGG resolution", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=B/b120210

- Roggenkamp, K.; Stefanescu, M. (2002), Algebra - Representation Theory, Springer, ISBN 978-0-7923-7114-4 .

| Original source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Verma module. Read more |