Homomorphism

In algebra, a homomorphism is a structure-preserving map between two algebraic structures of the same type (such as two groups, two rings, or two vector spaces). The word homomorphism comes from the Ancient Greek language: ὁμός (homos) meaning "same" and μορφή (morphe) meaning "form" or "shape". However, the word was apparently introduced to mathematics due to a (mis)translation of German ähnlich meaning "similar" to ὁμός meaning "same".[1] The term "homomorphism" appeared as early as 1892, when it was attributed to the German mathematician Felix Klein (1849–1925).[2]

Homomorphisms of vector spaces are also called linear maps, and their study is the subject of linear algebra.

The concept of homomorphism has been generalized, under the name of morphism, to many other structures that either do not have an underlying set, or are not algebraic. This generalization is the starting point of category theory.

A homomorphism may also be an isomorphism, an endomorphism, an automorphism, etc. (see below). Each of those can be defined in a way that may be generalized to any class of morphisms.

Definition

A homomorphism is a map between two algebraic structures of the same type (e.g. two groups, two fields, two vector spaces), that preserves the operations of the structures. This means a map between two sets , equipped with the same structure such that, if is an operation of the structure (supposed here, for simplification, to be a binary operation), then

for every pair , of elements of .[note 1] One says often that preserves the operation or is compatible with the operation.

Formally, a map preserves an operation of arity , defined on both and if

for all elements in .

The operations that must be preserved by a homomorphism include 0-ary operations, that is the constants. In particular, when an identity element is required by the type of structure, the identity element of the first structure must be mapped to the corresponding identity element of the second structure.

For example:

- A semigroup homomorphism is a map between semigroups that preserves the semigroup operation.

- A monoid homomorphism is a map between monoids that preserves the monoid operation and maps the identity element of the first monoid to that of the second monoid (the identity element is a 0-ary operation).

- A group homomorphism is a map between groups that preserves the group operation. This implies that the group homomorphism maps the identity element of the first group to the identity element of the second group, and maps the inverse of an element of the first group to the inverse of the image of this element. Thus a semigroup homomorphism between groups is necessarily a group homomorphism.

- A ring homomorphism is a map between rings that preserves the ring addition, the ring multiplication, and the multiplicative identity. Whether the multiplicative identity is to be preserved depends upon the definition of ring in use. If the multiplicative identity is not preserved, one has a rng homomorphism.

- A linear map is a homomorphism of vector spaces; that is, a group homomorphism between vector spaces that preserves the abelian group structure and scalar multiplication.

- A module homomorphism, also called a linear map between modules, is defined similarly.

- An algebra homomorphism is a map that preserves the algebra operations.

An algebraic structure may have more than one operation, and a homomorphism is required to preserve each operation. Thus a map that preserves only some of the operations is not a homomorphism of the structure, but only a homomorphism of the substructure obtained by considering only the preserved operations. For example, a map between monoids that preserves the monoid operation and not the identity element, is not a monoid homomorphism, but only a semigroup homomorphism.

The notation for the operations does not need to be the same in the source and the target of a homomorphism. For example, the real numbers form a group for addition, and the positive real numbers form a group for multiplication. The exponential function

satisfies

and is thus a homomorphism between these two groups. It is even an isomorphism (see below), as its inverse function, the natural logarithm, satisfies

and is also a group homomorphism.

Examples

The real numbers are a ring, having both addition and multiplication. The set of all 2×2 matrices is also a ring, under matrix addition and matrix multiplication. If we define a function between these rings as follows:

where r is a real number, then f is a homomorphism of rings, since f preserves both addition:

and multiplication:

For another example, the nonzero complex numbers form a group under the operation of multiplication, as do the nonzero real numbers. (Zero must be excluded from both groups since it does not have a multiplicative inverse, which is required for elements of a group.) Define a function from the nonzero complex numbers to the nonzero real numbers by

That is, is the absolute value (or modulus) of the complex number . Then is a homomorphism of groups, since it preserves multiplication:

Note that f cannot be extended to a homomorphism of rings (from the complex numbers to the real numbers), since it does not preserve addition:

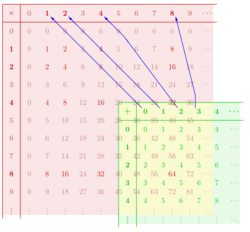

As another example, the diagram shows a monoid homomorphism from the monoid to the monoid . Due to the different names of corresponding operations, the structure preservation properties satisfied by amount to and .

A composition algebra over a field has a quadratic form, called a norm, , which is a group homomorphism from the multiplicative group of to the multiplicative group of .

Special homomorphisms

Several kinds of homomorphisms have a specific name, which is also defined for general morphisms.

Isomorphism

An isomorphism between algebraic structures of the same type is commonly defined as a bijective homomorphism.[3]: 134 [4]: 28

In the more general context of category theory, an isomorphism is defined as a morphism that has an inverse that is also a morphism. In the specific case of algebraic structures, the two definitions are equivalent, although they may differ for non-algebraic structures, which have an underlying set.

More precisely, if

is a (homo)morphism, it has an inverse if there exists a homomorphism

such that

If and have underlying sets, and has an inverse , then is bijective. In fact, is injective, as implies , and is surjective, as, for any in , one has , and is the image of an element of .

Conversely, if is a bijective homomorphism between algebraic structures, let be the map such that is the unique element of such that . One has and it remains only to show that g is a homomorphism. If is a binary operation of the structure, for every pair , of elements of , one has

and is thus compatible with As the proof is similar for any arity, this shows that is a homomorphism.

This proof does not work for non-algebraic structures. For example, for topological spaces, a morphism is a continuous map, and the inverse of a bijective continuous map is not necessarily continuous. An isomorphism of topological spaces, called homeomorphism or bicontinuous map, is thus a bijective continuous map, whose inverse is also continuous.

Endomorphism

An endomorphism is a homomorphism whose domain equals the codomain, or, more generally, a morphism whose source is equal to its target.[3]: 135

The endomorphisms of an algebraic structure, or of an object of a category, form a monoid under composition.

The endomorphisms of a vector space or of a module form a ring. In the case of a vector space or a free module of finite dimension, the choice of a basis induces a ring isomorphism between the ring of endomorphisms and the ring of square matrices of the same dimension.

Automorphism

An automorphism is an endomorphism that is also an isomorphism.[3]: 135

The automorphisms of an algebraic structure or of an object of a category form a group under composition, which is called the automorphism group of the structure.

Many groups that have received a name are automorphism groups of some algebraic structure. For example, the general linear group is the automorphism group of a vector space of dimension over a field .

The automorphism groups of fields were introduced by Évariste Galois for studying the roots of polynomials, and are the basis of Galois theory.

Monomorphism

For algebraic structures, monomorphisms are commonly defined as injective homomorphisms.[3]: 134 [4]: Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.

In the more general context of category theory, a monomorphism is defined as a morphism that is left cancelable.[5] This means that a (homo)morphism is a monomorphism if, for any pair , of morphisms from any other object to , then implies .

These two definitions of monomorphism are equivalent for all common algebraic structures. More precisely, they are equivalent for fields, for which every homomorphism is a monomorphism, and for varieties of universal algebra, that is algebraic structures for which operations and axioms (identities) are defined without any restriction (the fields do not form a variety, as the multiplicative inverse is defined either as a unary operation or as a property of the multiplication, which are, in both cases, defined only for nonzero elements).

In particular, the two definitions of a monomorphism are equivalent for sets, magmas, semigroups, monoids, groups, rings, fields, vector spaces and modules.

A split monomorphism is a homomorphism that has a left inverse and thus it is itself a right inverse of that other homomorphism. That is, a homomorphism is a split monomorphism if there exists a homomorphism such that A split monomorphism is always a monomorphism, for both meanings of monomorphism. For sets and vector spaces, every monomorphism is a split monomorphism, but this property does not hold for most common algebraic structures.

Proof of the equivalence of the two definitions of monomorphisms

|

|---|

|

An injective homomorphism is left cancelable: If one has for every in , the common source of and . If is injective, then , and thus . This proof works not only for algebraic structures, but also for any category whose objects are sets and arrows are maps between these sets. For example, an injective continuous map is a monomorphism in the category of topological spaces. For proving that, conversely, a left cancelable homomorphism is injective, it is useful to consider a free object on . Given a variety of algebraic structures a free object on is a pair consisting of an algebraic structure of this variety and an element of satisfying the following universal property: for every structure of the variety, and every element of , there is a unique homomorphism such that . For example, for sets, the free object on is simply ; for semigroups, the free object on is which, as, a semigroup, is isomorphic to the additive semigroup of the positive integers; for monoids, the free object on is which, as, a monoid, is isomorphic to the additive monoid of the nonnegative integers; for groups, the free object on is the infinite cyclic group which, as, a group, is isomorphic to the additive group of the integers; for rings, the free object on is the polynomial ring for vector spaces or modules, the free object on is the vector space or free module that has as a basis. If a free object over exists, then every left cancelable homomorphism is injective: let be a left cancelable homomorphism, and and be two elements of such . By definition of the free object , there exist homomorphisms and from to such that and . As , one has by the uniqueness in the definition of a universal property. As is left cancelable, one has , and thus . Therefore, is injective. Existence of a free object on for a variety (see also Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.): For building a free object over , consider the set of the well-formed formulas built up from and the operations of the structure. Two such formulas are said equivalent if one may pass from one to the other by applying the axioms (identities of the structure). This defines an equivalence relation, if the identities are not subject to conditions, that is if one works with a variety. Then the operations of the variety are well defined on the set of equivalence classes of for this relation. It is straightforward to show that the resulting object is a free object on . |

Epimorphism

In algebra, epimorphisms are often defined as surjective homomorphisms.[3]<span title="Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.">: Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1. [4]<span title="Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.">: Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1. On the other hand, in category theory, epimorphisms are defined as right cancelable morphisms.[5] This means that a (homo)morphism is an epimorphism if, for any pair , of morphisms from to any other object , the equality implies .

A surjective homomorphism is always right cancelable, but the converse is not always true for algebraic structures. However, the two definitions of epimorphism are equivalent for sets, vector spaces, abelian groups, modules (see below for a proof), and groups.[6] The importance of these structures in all mathematics, especially in linear algebra and homological algebra, may explain the coexistence of two non-equivalent definitions.

Algebraic structures for which there exist non-surjective epimorphisms include semigroups and rings. The most basic example is the inclusion of integers into rational numbers, which is a homomorphism of rings and of multiplicative semigroups. For both structures it is a monomorphism and a non-surjective epimorphism, but not an isomorphism.[5][7]

A wide generalization of this example is the localization of a ring by a multiplicative set. Every localization is a ring epimorphism, which is not, in general, surjective. As localizations are fundamental in commutative algebra and algebraic geometry, this may explain why in these areas, the definition of epimorphisms as right cancelable homomorphisms is generally preferred.

A split epimorphism is a homomorphism that has a right inverse and thus it is itself a left inverse of that other homomorphism. That is, a homomorphism is a split epimorphism if there exists a homomorphism such that A split epimorphism is always an epimorphism, for both meanings of epimorphism. For sets and vector spaces, every epimorphism is a split epimorphism, but this property does not hold for most common algebraic structures.

In summary, one has

the last implication is an equivalence for sets, vector spaces, modules, abelian groups, and groups; the first implication is an equivalence for sets and vector spaces.

Equivalence of the two definitions of epimorphism

|

|---|

|

Let be a homomorphism. We want to prove that if it is not surjective, it is not right cancelable. In the case of sets, let be an element of that not belongs to , and define such that is the identity function, and that for every except that is any other element of . Clearly is not right cancelable, as and In the case of vector spaces, abelian groups and modules, the proof relies on the existence of cokernels and on the fact that the zero maps are homomorphisms: let be the cokernel of , and be the canonical map, such that . Let be the zero map. If is not surjective, , and thus (one is a zero map, while the other is not). Thus is not cancelable, as (both are the zero map from to ). |

Kernel

Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.

Any homomorphism defines an equivalence relation on by if and only if . The relation is called the kernel of . It is a congruence relation on . The quotient set can then be given a structure of the same type as , in a natural way, by defining the operations of the quotient set by , for each operation of . In that case the image of in under the homomorphism is necessarily isomorphic to ; this fact is one of the isomorphism theorems.

When the algebraic structure is a group for some operation, the equivalence class of the identity element of this operation suffices to characterize the equivalence relation. In this case, the quotient by the equivalence relation is denoted by (usually read as " mod "). Also in this case, it is , rather than , that is called the kernel of . The kernels of homomorphisms of a given type of algebraic structure are naturally equipped with some structure. This structure type of the kernels is the same as the considered structure, in the case of abelian groups, vector spaces and modules, but is different and has received a specific name in other cases, such as normal subgroup for kernels of group homomorphisms and ideals for kernels of ring homomorphisms (in the case of non-commutative rings, the kernels are the two-sided ideals).

Relational structures

In model theory, the notion of an algebraic structure is generalized to structures involving both operations and relations. Let L be a signature consisting of function and relation symbols, and A, B be two L-structures. Then a homomorphism from A to B is a mapping h from the domain of A to the domain of B such that

- h(FA(a1,...,an)) = FB(h(a1),...,h(an)) for each n-ary function symbol F in L,

- RA(a1,...,an) implies RB(h(a1),...,h(an)) for each n-ary relation symbol R in L.

In the special case with just one binary relation, we obtain the notion of a graph homomorphism.[8]

Formal language theory

Homomorphisms are also used in the study of formal languages[9] and are often briefly referred to as morphisms.[10] Given alphabets and , a function such that for all is called a homomorphism on .[note 2] If is a homomorphism on and denotes the empty string, then is called an -free homomorphism when for all in .

A homomorphism on that satisfies for all is called a -uniform homomorphism.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1. If for all (that is, is 1-uniform), then is also called a coding or a projection. The set of words formed from the alphabet may be thought of as the free monoid generated by . Here the monoid operation is concatenation and the identity element is the empty word. From this perspective, a language homomorphism is precisely a monoid homomorphism.[note 3]

See also

- Diffeomorphism

- Homomorphic encryption

- Homomorphic secret sharing – a simplistic decentralized voting protocol

- Morphism

- Quasimorphism

Notes

- ↑ As it is often the case, but not always, the same symbol for the operation of both and was used here.

- ↑ The ∗ denotes the Kleene star operation, while Σ∗ denotes the set of words formed from the alphabet Σ, including the empty word. Juxtaposition of terms denotes concatenation. For example, h(u) h(v) denotes the concatenation of h(u) with h(v).

- ↑ We are assured that a language homomorphism h maps the empty word ε to the empty word. Since h(ε) = h(εε) = h(ε)h(ε), the number w of characters in h(ε) equals the number 2w of characters in h(ε)h(ε). Hence w = 0 and h(ε) has null length.

Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.

Citations

- ↑ Fricke, Robert (1897–1912) (in de). Vorlesungen über die Theorie der automorphen Functionen. B. G. Teubner. OCLC 29857037. https://archive.org/details/vorlesungenber01fricuoft/page/n5/mode/2up.

- ↑ See:

- Ritter, Ernst (1892). "Die eindeutigen automorphen Formen vom Geschlecht Null, eine Revision und Erweiterung der Poincaré'schen Sätze" (in de). Mathematische Annalen 41: 1–82. doi:10.1007/BF01443449. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044102918109&view=1up&seq=15. "[footnote p. 22:] Ich will nach einem Vorschlage von Hrn. Prof. Klein statt der umständlichen und nicht immer ausreichenden Bezeichnungen: 'holoedrisch, bezw. hemiedrisch u.s.w. isomorph' die Benennung 'isomorph' auf den Fall des holoedrischen Isomorphismus zweier Gruppen einschränken, sonst aber von 'Homomorphismus' sprechen, ...".

- Fricke, Robert (1892). "Ueber den arithmetischen Charakter der zu den Verzweigungen (2,3,7) und (2,4,7) gehörenden Dreiecksfunctionen" (in de). Mathematische Annalen 41 (3): 443–468. doi:10.1007/BF01443421. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044102918109&view=1up&seq=471. "[p. 466] Hierdurch ist, wie man sofort überblickt, eine homomorphe*) Beziehung der Gruppe Γ(63) auf die Gruppe der mod. n incongruenten Substitutionen mit rationalen ganzen Coefficienten der Determinante 1 begründet. ... *) Im Anschluss an einen von Hrn. Klein bei seinen neueren Vorlesungen eingeführten Brauch schreibe ich an Stelle der bisherigen Bezeichnung 'meroedrischer Isomorphismus' die sinngemässere 'Homomorphismus'.".

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Birkhoff, Garrett (1967). Lattice theory. American Mathematical Society Colloquium Publications. 25 (3rd ed.). Providence, Rhode Island: American Mathematical Society. ISBN 978-0-8218-1025-5.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Mac Lane, Saunders (1971). Categories for the Working Mathematician. Graduate Texts in Mathematics. 5. Springer. Exercise 4 in section I.5. ISBN 0-387-90036-5.

- ↑ Linderholm, C. E. (1970). "A group epimorphism is surjective". The American Mathematical Monthly 77 (2): 176–177. doi:10.1080/00029890.1970.11992448.

- ↑ Dăscălescu, Sorin; Năstăsescu, Constantin; Raianu, Șerban (2001). Hopf Algebra: An Introduction. Pure and Applied Mathematics. 235. New York City: Marcel Dekker. p. 363. ISBN 0824704819.

- ↑ For a detailed discussion of relational homomorphisms and isomorphisms see Schmidt, Gunther (2010). Relational Mathematics. Cambridge University Press. Section 17.3. ISBN 978-0-521-76268-7.

- ↑ Ginsburg, Seymour (1975). Algebraic and automata theoretic properties of formal languages. North-Holland. ISBN 0-7204-2506-9.

- ↑ Harju, T.; Karhumӓki, J. (1997). "Morphisms". in Rozenberg, G.; Salomaa, A.. Handbook of Formal Languages. I. Springer. ISBN 3-540-61486-9.

Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.

References

- Krieger, Dalia (2006). "On critical exponents in fixed points of non-erasing morphisms". Developments in language theory : 10th international conference, DLT 2006, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, June 26-29, 2006 : proceedings. Berlin: Springer. pp. 280–291. ISBN 978-3-540-35430-7. OCLC 262693179.

- Stanley N. Burris; H.P. Sankappanavar (2012). A Course in Universal Algebra. S. Burris and H.P. Sankappanavar. ISBN 978-0-9880552-0-9. http://www.math.uwaterloo.ca/~snburris/htdocs/UALG/univ-algebra2012.pdf.

- Mac Lane, Saunders (1971), Categories for the Working Mathematician, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, 5, Springer, ISBN 0-387-90036-5

- Fraleigh, John B.; Katz, Victor J. (2003), A First Course in Abstract Algebra, Addison-Wesley, ISBN 978-1-292-02496-7

Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.