Residue (complex analysis)

| Mathematical analysis → Complex analysis |

| Complex analysis |

|---|

|

| Complex numbers |

| Complex functions |

| Basic Theory |

| Geometric function theory |

| People |

|

|

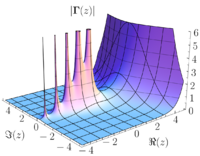

In mathematics, more specifically complex analysis, the residue is a complex number proportional to the contour integral of a meromorphic function along a path enclosing one of its singularities. (More generally, residues can be calculated for any function [math]\displaystyle{ f\colon \mathbb{C} \setminus \{a_k\}_k \rightarrow \mathbb{C} }[/math] that is holomorphic except at the discrete points {ak}k, even if some of them are essential singularities.) Residues can be computed quite easily and, once known, allow the determination of general contour integrals via the residue theorem.

Definition

The residue of a meromorphic function [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] at an isolated singularity [math]\displaystyle{ a }[/math], often denoted [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Res}(f,a) }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Res}_a(f) }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \mathop{\operatorname{Res}}_{z=a}f(z) }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ \mathop{\operatorname{res}}_{z=a}f(z) }[/math], is the unique value [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ f(z)- R/(z-a) }[/math] has an analytic antiderivative in a punctured disk [math]\displaystyle{ 0\lt \vert z-a\vert\lt \delta }[/math].

Alternatively, residues can be calculated by finding Laurent series expansions, and one can define the residue as the coefficient a−1 of a Laurent series.

The concept can be used to provide contour integration values of certain contour integral problems considered in the residue theorem. According to the residue theorem, for a meromorphic function [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math], the residue at point [math]\displaystyle{ a_k }[/math] is given as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Res}(f,a_k) = {1 \over 2\pi i} \oint_\gamma f(z)\,dz \, . }[/math]

where γ is a positively oriented simple closed curve around [math]\displaystyle{ a_k }[/math] and not including any other singularities on or inside the curve.

The definition of a residue can be generalized to arbitrary Riemann surfaces. Suppose [math]\displaystyle{ \omega }[/math] is a 1-form on a Riemann surface. Let [math]\displaystyle{ \omega }[/math] be meromorphic at some point [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math], so that we may write [math]\displaystyle{ \omega }[/math] in local coordinates as [math]\displaystyle{ f(z) \; dz }[/math]. Then, the residue of [math]\displaystyle{ \omega }[/math] at [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] is defined to be the residue of [math]\displaystyle{ f(z) }[/math] at the point corresponding to [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math].

Contour integration

Contour integral of a monomial

Computing the residue of a monomial

- [math]\displaystyle{ \oint_C z^k \, dz }[/math]

makes most residue computations easy to do. Since path integral computations are homotopy invariant, we will let [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] be the circle with radius [math]\displaystyle{ 1 }[/math] going counter clockwise. Then, using the change of coordinates [math]\displaystyle{ z \to e^{i\theta} }[/math] we find that

- [math]\displaystyle{ dz \to d(e^{i\theta}) = ie^{i\theta} \, d\theta }[/math]

hence our integral now reads as

- [math]\displaystyle{ \oint_C z^k dz = \int_0^{2\pi} i e^{i(k+1)\theta} \, d\theta = \begin{cases} 2\pi i & \text{if } k = -1, \\ 0 & \text{otherwise}. \end{cases} }[/math]

Thus, the residue of [math]\displaystyle{ z^k }[/math] is 1 if integer [math]\displaystyle{ k=-1 }[/math] and 0 otherwise.

Generalization to Laurent series

If a function is expressed as a Laurent series expansion around c as follows:[math]\displaystyle{ f(z) = \sum_{n=-\infty}^\infty a_n(z-c)^n. }[/math]Then, the residue at the point c is calculated as:[math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Res}(f,c) = {1 \over 2\pi i} \oint_\gamma f(z)\,dz = {1 \over 2\pi i} \sum_{n=-\infty}^\infty \oint_\gamma a_n(z-c)^n \,dz = a_{-1} }[/math]using the results from contour integral of a monomial for counter clockwise contour integral [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma }[/math] around a point c. Hence, if a Laurent series representation of a function exists around c, then its residue around c is known by the coefficient of the [math]\displaystyle{ (z-c)^{-1} }[/math] term.

Application in Residue theorem

For a meromorphic function [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math], with a finite set of singularities within a positively oriented simple closed curve [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] which does not pass through any singularity, the value of the contour integral is given according to residue theorem, as:[math]\displaystyle{ \oint_C f(z)\, dz = 2\pi i \sum_{k=1}^n \operatorname{I}(C, a_k) \operatorname{Res}(f, a_k). }[/math]where [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{I}(C, a_k) }[/math], the winding number, is [math]\displaystyle{ 1 }[/math] if [math]\displaystyle{ a_k }[/math] is in the interior of [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ 0 }[/math] if not, simplifying to:[math]\displaystyle{ \oint_\gamma f(z)\, dz = 2\pi i \sum \operatorname{Res}(f, a_k) }[/math]where [math]\displaystyle{ a_k }[/math] are all isolated singularities within the contour [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math].

Calculation of residues

Suppose a punctured disk D = {z : 0 < |z − c| < R} in the complex plane is given and f is a holomorphic function defined (at least) on D. The residue Res(f, c) of f at c is the coefficient a−1 of (z − c)−1 in the Laurent series expansion of f around c. Various methods exist for calculating this value, and the choice of which method to use depends on the function in question, and on the nature of the singularity.

According to the residue theorem, we have:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Res}(f,c) = {1 \over 2\pi i} \oint_\gamma f(z)\,dz }[/math]

where γ traces out a circle around c in a counterclockwise manner and does not pass through or contain other singularities within it. We may choose the path γ to be a circle of radius ε around c. Since ε is can be small as we desire it can be made to contain only the singularity of c due to nature of isolated singularities. This may be used for calculation in cases where the integral can be calculated directly, but it is usually the case that residues are used to simplify calculation of integrals, and not the other way around.

Removable singularities

If the function f can be continued to a holomorphic function on the whole disk [math]\displaystyle{ |y-c|\lt R }[/math], then Res(f, c) = 0. The converse is not generally true.

Simple poles

At a simple pole c, the residue of f is given by:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Res}(f,c)=\lim_{z\to c}(z-c)f(z). }[/math]

If that limit does not exist, there is an essential singularity there. If it is 0 then it is either analytic there or there is a removable singularity. If it is equal to infinity then the order is higher than 1.

It may be that the function f can be expressed as a quotient of two functions, [math]\displaystyle{ f(z)=\frac{g(z)}{h(z)} }[/math], where g and h are holomorphic functions in a neighbourhood of c, with h(c) = 0 and h'(c) ≠ 0. In such a case, L'Hôpital's rule can be used to simplify the above formula to:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \operatorname{Res}(f,c) & =\lim_{z\to c}(z-c)f(z) = \lim_{z\to c}\frac{z g(z) - cg(z)}{h(z)} \\[4pt] & = \lim_{z\to c}\frac{g(z) + z g'(z) - cg'(z)}{h'(z)} = \frac{g(c)}{h'(c)}. \end{align} }[/math]

Limit formula for higher-order poles

More generally, if c is a pole of order n, then the residue of f around z = c can be found by the formula:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Res}(f,c) = \frac{1}{(n-1)!} \lim_{z \to c} \frac{d^{n-1}}{dz^{n-1}} \left( (z-c)^n f(z) \right). }[/math]

This formula can be very useful in determining the residues for low-order poles. For higher-order poles, the calculations can become unmanageable, and series expansion is usually easier. For essential singularities, no such simple formula exists, and residues must usually be taken directly from series expansions.

Residue at infinity

In general, the residue at infinity is defined as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Res}(f(z), \infty) = -\operatorname{Res}\left(\frac{1}{z^2} f\left(\frac 1 z \right), 0\right). }[/math]

If the following condition is met:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \lim_{|z| \to \infty} f(z) = 0, }[/math]

then the residue at infinity can be computed using the following formula:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Res}(f, \infty) = -\lim_{|z| \to \infty} z \cdot f(z). }[/math]

If instead

- [math]\displaystyle{ \lim_{|z| \to \infty} f(z) = c \neq 0, }[/math]

then the residue at infinity is

- [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Res}(f, \infty) = \lim_{|z| \to \infty} z^2 \cdot f'(z). }[/math]

For holomorphic functions the sum of the residues at the isolated singularities plus the residue at infinity is zero which gives:

[math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Res}(f(z), \infty) = -\sum_k \operatorname{Res}\left(f\left(z\right), a_k\right). }[/math]

Series methods

If parts or all of a function can be expanded into a Taylor series or Laurent series, which may be possible if the parts or the whole of the function has a standard series expansion, then calculating the residue is significantly simpler than by other methods. The residue of the function is simply given by the coefficient of [math]\displaystyle{ (z-c)^{-1} }[/math] in the Laurent series expansion of the function.

Examples

Residue from series expansion

Example 1

As an example, consider the contour integral

- [math]\displaystyle{ \oint_C {e^z \over z^5}\,dz }[/math]

where C is some simple closed curve about 0.

Let us evaluate this integral using a standard convergence result about integration by series. We can substitute the Taylor series for [math]\displaystyle{ e^z }[/math] into the integrand. The integral then becomes

- [math]\displaystyle{ \oint_C {1 \over z^5}\left(1+z+{z^2 \over 2!} + {z^3\over 3!} + {z^4 \over 4!} + {z^5 \over 5!} + {z^6 \over 6!} + \cdots\right)\,dz. }[/math]

Let us bring the 1/z5 factor into the series. The contour integral of the series then writes

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} & \oint_C \left({1 \over z^5}+{z \over z^5}+{z^2 \over 2!\;z^5} + {z^3\over 3!\;z^5} + {z^4 \over 4!\;z^5} + {z^5 \over 5!\;z^5} + {z^6 \over 6!\;z^5} + \cdots\right)\,dz \\[4pt] = {} & \oint_C \left({1 \over\;z^5}+{1 \over\;z^4}+{1 \over 2!\;z^3} + {1\over 3!\;z^2} + {1 \over 4!\;z} + {1\over\;5!} + {z \over 6!} + \cdots\right)\,dz. \end{align} }[/math]

Since the series converges uniformly on the support of the integration path, we are allowed to exchange integration and summation. The series of the path integrals then collapses to a much simpler form because of the previous computation. So now the integral around C of every other term not in the form cz−1 is zero, and the integral is reduced to

- [math]\displaystyle{ \oint_C {1 \over 4!\;z} \,dz= {1 \over 4!} \oint_C{1 \over z}\,dz={1 \over 4!}(2\pi i) = {\pi i \over 12}. }[/math]

The value 1/4! is the residue of ez/z5 at z = 0, and is denoted

- [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Res}_0 {e^z \over z^5}, \text{ or } \operatorname{Res}_{z=0} {e^z \over z^5}, \text{ or } \operatorname{Res}(f,0) \text{ for } f={e^z \over z^5}. }[/math]

Example 2

As a second example, consider calculating the residues at the singularities of the function[math]\displaystyle{ f(z) = {\sin z \over z^2-z} }[/math]which may be used to calculate certain contour integrals. This function appears to have a singularity at z = 0, but if one factorizes the denominator and thus writes the function as[math]\displaystyle{ f(z) = {\sin z \over z(z - 1)} }[/math]it is apparent that the singularity at z = 0 is a removable singularity and then the residue at z = 0 is therefore 0. The only other singularity is at z = 1. Recall the expression for the Taylor series for a function g(z) about z = a:[math]\displaystyle{ g(z) = g(a) + g'(a)(z-a) + {g''(a)(z-a)^2 \over 2!} + {g'''(a)(z-a)^3 \over 3!}+ \cdots }[/math]So, for g(z) = sin z and a = 1 we have[math]\displaystyle{ \sin z = \sin 1 + (\cos 1)(z-1)+{-(\sin 1)(z-1)^2 \over 2!} + {-(\cos 1)(z-1)^3 \over 3!} + \cdots. }[/math]and for g(z) = 1/z and a = 1 we have[math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{z} = \frac1 {(z - 1) + 1} = 1 - (z - 1) + (z - 1)^2 - (z - 1)^3 + \cdots. }[/math]Multiplying those two series and introducing 1/(z − 1) gives us[math]\displaystyle{ \frac{\sin z} {z(z - 1)} = {\sin 1 \over z-1} + (\cos 1 - \sin 1) + (z-1) \left(-\frac{\sin 1}{2!} - \cos1 + \sin 1\right) + \cdots. }[/math]So the residue of f(z) at z = 1 is sin 1.

Example 3

The next example shows that, computing a residue by series expansion, a major role is played by the Lagrange inversion theorem. Let[math]\displaystyle{ u(z) := \sum_{k\geq 1}u_k z^k }[/math]be an entire function, and let[math]\displaystyle{ v(z) := \sum_{k\geq 1}v_k z^k }[/math]with positive radius of convergence, and with [math]\displaystyle{ v_1 \neq 0 }[/math]. So [math]\displaystyle{ v(z) }[/math] has a local inverse [math]\displaystyle{ V(z) }[/math] at 0, and [math]\displaystyle{ u(1/V(z)) }[/math] is meromorphic at 0. Then we have:[math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Res}_0 \big(u(1/V(z))\big) = \sum_{k=0}^\infty ku_k v_k. }[/math]Indeed,[math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Res}_0\big(u(1/V(z))\big) = \operatorname{Res}_0 \left(\sum_{k\geq 1} u_k V(z)^{-k}\right) = \sum_{k\geq 1} u_k \operatorname{Res}_0 \big(V(z)^{-k}\big) }[/math]because the first series converges uniformly on any small circle around 0. Using the Lagrange inversion theorem[math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Res}_0 \big(V(z)^{-k}\big) = kv_k, }[/math]and we get the above expression. For example, if [math]\displaystyle{ u(z) = z + z^2 }[/math] and also [math]\displaystyle{ v(z) = z + z^2 }[/math], then[math]\displaystyle{ V(z) = \frac{2z}{1 + \sqrt{1 + 4z}} }[/math]and[math]\displaystyle{ u(1/V(z)) = \frac{1 + \sqrt{1 + 4z}}{2z} + \frac{1 + 2z + \sqrt{1 + 4z}}{2z^2}. }[/math]The first term contributes 1 to the residue, and the second term contributes 2 since it is asymptotic to [math]\displaystyle{ 1/z^2 + 2/z }[/math].

Note that, with the corresponding stronger symmetric assumptions on [math]\displaystyle{ u(z) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ v(z) }[/math], it also follows[math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{Res}_0 \left(u(1/V)\right) = \operatorname{Res}_0\left(v(1/U)\right), }[/math]where [math]\displaystyle{ U(z) }[/math] is a local inverse of [math]\displaystyle{ u(z) }[/math] at 0.

See also

- The residue theorem relates a contour integral around some of a function's poles to the sum of their residues

- Cauchy's integral formula

- Cauchy's integral theorem

- Mittag-Leffler's theorem

- Methods of contour integration

- Morera's theorem

- Partial fractions in complex analysis

References

- Ahlfors, Lars (1979). Complex Analysis. McGraw Hill.

- Marsden, Jerrold E.; Hoffman, Michael J. (1998). Basic Complex Analysis (3rd ed.). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-2877-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=Z26tKIymJjMC&q=residue.

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Residue of an analytic function", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=p/r081560

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Complex Residue". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/ComplexResidue.html.

|