Young's inequality for products

In mathematics, Young's inequality for products is a mathematical inequality about the product of two numbers.[1] The inequality is named after William Henry Young and should not be confused with Young's convolution inequality.

Young's inequality for products can be used to prove Hölder's inequality. It is also widely used to estimate the norm of nonlinear terms in PDE theory, since it allows one to estimate a product of two terms by a sum of the same terms raised to a power and scaled.

Standard version for conjugate Hölder exponents

The standard form of the inequality is the following:

Theorem — If [math]\displaystyle{ a \geq 0 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ b \geq 0 }[/math] are nonnegative real numbers and if [math]\displaystyle{ p \gt 1 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ q \gt 1 }[/math] are real numbers such that [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{p} + \frac{1}{q} = 1, }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ a b ~\leq~ \frac{a^p}{p} + \frac{b^q}{q}. }[/math]

Equality holds if and only if [math]\displaystyle{ a^p = b^q. }[/math]

It can be used to prove Hölder's inequality.

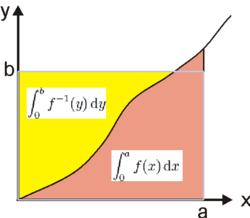

Since [math]\displaystyle{ \tfrac{1}{p} + \tfrac{1}{q} = 1, }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ p - 1 = \tfrac{1}{q-1}. }[/math] A graph [math]\displaystyle{ y = x^{p-1} }[/math] on the [math]\displaystyle{ x y }[/math]-plane is thus also a graph [math]\displaystyle{ x = y^{q-1}. }[/math] From sketching a visual representation of the integrals of the area between this curve and the axes, and the area in the rectangle bounded by the lines [math]\displaystyle{ x=0, x=a, y=0, y=b, }[/math] and the fact that [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] is always increasing for increasing [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] and vice versa, we can see that [math]\displaystyle{ \int^a_0 x^{p-1} \mathrm{d}x }[/math] upper bounds the area of the rectangle below the curve (with equality when [math]\displaystyle{ b\ge a^{p-1} }[/math]) and [math]\displaystyle{ \int^b_0 y^{q-1} \mathrm{d}y }[/math] upper bounds the area of the rectangle above the curve (with equality when [math]\displaystyle{ b\le a^{p-1} }[/math]). Thus, [math]\displaystyle{ \int^a_0 x^{p-1} \mathrm{d}x + \int^b_0 y^{q-1} \mathrm{d}y \geq ab, }[/math] with equality when [math]\displaystyle{ b=a^{p-1} }[/math] (or equivalently, [math]\displaystyle{ a^p=b^q }[/math]). Young's inequality follows from evaluating the integrals. (See below for a generalization.)

This form of Young's inequality can also be proved via Jensen's inequality.

The claim is certainly true if [math]\displaystyle{ a = 0 }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ b = 0 }[/math] so henceforth assume that [math]\displaystyle{ a \gt 0 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ b \gt 0. }[/math] Put [math]\displaystyle{ t = 1/p }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ (1 - t) = 1/q. }[/math] Because the logarithm function is concave, [math]\displaystyle{ \ln\left(t a^p + (1-t) b^q\right) ~\geq~ t \ln\left(a^p\right) + (1-t) \ln\left(b^q\right) = \ln(a) + \ln(b) = \ln(ab) }[/math] with the equality holding if and only if [math]\displaystyle{ a^p = b^q. }[/math] Young's inequality follows by exponentiating.

Young's inequality may equivalently be written as [math]\displaystyle{ a^\alpha b^\beta \leq \alpha a + \beta b, \qquad\, 0 \leq \alpha, \beta \leq 1, \quad\ \alpha + \beta = 1. }[/math]

Where this is just the concavity of the logarithm function. Equality holds if and only if [math]\displaystyle{ a = b }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ \{\alpha, \beta\} = \{0, 1\}. }[/math] This also follows from the weighted AM-GM inequality.

Generalizations

Theorem[4] — Suppose [math]\displaystyle{ a \gt 0 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ b \gt 0. }[/math] If [math]\displaystyle{ 1 \lt p \lt \infty }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ q }[/math] are such that [math]\displaystyle{ \tfrac{1}{p} + \tfrac{1}{q} = 1 }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ a b ~=~ \min_{0 \lt t \lt \infty} \left(\frac{t^p a^p}{p} + \frac{t^{-q} b^q}{q}\right). }[/math]

Using [math]\displaystyle{ t := 1 }[/math] and replacing [math]\displaystyle{ a }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ a^{1/p} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ b }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ b^{1/q} }[/math] results in the inequality: [math]\displaystyle{ a^{1/p} \, b^{1/q} ~\leq~ \frac{a}{p} + \frac{b}{q}, }[/math] which is useful for proving Hölder's inequality.

Define a real-valued function [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] on the positive real numbers by [math]\displaystyle{ f(t) ~=~ \frac{t^p a^p}{p} + \frac{t^{-q} b^q}{q} }[/math] for every [math]\displaystyle{ t \gt 0 }[/math] and then calculate its minimum.

Theorem — If [math]\displaystyle{ 0 \leq p_i \leq 1 }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_i p_i = 1 }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ \prod_i {a_i}^{p_i} ~\leq~ \sum_i p_i a_i. }[/math] Equality holds if and only if all the [math]\displaystyle{ a_i }[/math]s with non-zero [math]\displaystyle{ p_i }[/math]s are equal.

Elementary case

An elementary case of Young's inequality is the inequality with exponent [math]\displaystyle{ 2, }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ a b \leq \frac{a^2}{2} + \frac{b^2}{2}, }[/math] which also gives rise to the so-called Young's inequality with [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon }[/math] (valid for every [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon \gt 0 }[/math]), sometimes called the Peter–Paul inequality. [5] This name refers to the fact that tighter control of the second term is achieved at the cost of losing some control of the first term – one must "rob Peter to pay Paul" [math]\displaystyle{ a b ~\leq~ \frac{a^2}{2 \varepsilon} + \frac{\varepsilon b^2}{2}. }[/math]

Proof: Young's inequality with exponent [math]\displaystyle{ 2 }[/math] is the special case [math]\displaystyle{ p = q = 2. }[/math] However, it has a more elementary proof.

Start by observing that the square of every real number is zero or positive. Therefore, for every pair of real numbers [math]\displaystyle{ a }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ b }[/math] we can write: [math]\displaystyle{ 0 \leq (a-b)^2 }[/math] Work out the square of the right hand side: [math]\displaystyle{ 0 \leq a^2 - 2 a b + b^2 }[/math] Add [math]\displaystyle{ 2a b }[/math] to both sides: [math]\displaystyle{ 2 a b \leq a^2 + b^2 }[/math] Divide both sides by 2 and we have Young's inequality with exponent [math]\displaystyle{ 2: }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ a b \leq \frac{a^2}{2} + \frac{b^2}{2} }[/math]

Young's inequality with [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon }[/math] follows by substituting [math]\displaystyle{ a' }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ b' }[/math] as below into Young's inequality with exponent [math]\displaystyle{ 2: }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ a' = a/\sqrt{\varepsilon}, \; b' = \sqrt{\varepsilon} b. }[/math]

Matricial generalization

T. Ando proved a generalization of Young's inequality for complex matrices ordered by Loewner ordering.[6] It states that for any pair [math]\displaystyle{ A, B }[/math] of complex matrices of order [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] there exists a unitary matrix [math]\displaystyle{ U }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ U^* |A B^*| U \preceq \tfrac{1}{p} |A|^p + \tfrac{1}{q} |B|^q, }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ {}^* }[/math] denotes the conjugate transpose of the matrix and [math]\displaystyle{ |A| = \sqrt{A^* A}. }[/math]

Standard version for increasing functions

For the standard version[7][8] of the inequality, let [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] denote a real-valued, continuous and strictly increasing function on [math]\displaystyle{ [0, c] }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ c \gt 0 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ f(0) = 0. }[/math] Let [math]\displaystyle{ f^{-1} }[/math] denote the inverse function of [math]\displaystyle{ f. }[/math] Then, for all [math]\displaystyle{ a \in [0, c] }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ b \in [0, f(c)], }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ a b ~\leq~ \int_0^a f(x)\,dx + \int_0^b f^{-1}(x)\,dx }[/math] with equality if and only if [math]\displaystyle{ b = f(a). }[/math]

With [math]\displaystyle{ f(x) = x^{p-1} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ f^{-1}(y) = y^{q-1}, }[/math] this reduces to standard version for conjugate Hölder exponents.

For details and generalizations we refer to the paper of Mitroi & Niculescu.[9]

Generalization using Fenchel–Legendre transforms

By denoting the convex conjugate of a real function [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] by [math]\displaystyle{ g, }[/math] we obtain [math]\displaystyle{ a b ~\leq~ f(a) + g(b). }[/math] This follows immediately from the definition of the convex conjugate. For a convex function [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] this also follows from the Legendre transformation.

More generally, if [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] is defined on a real vector space [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] and its convex conjugate is denoted by [math]\displaystyle{ f^\star }[/math] (and is defined on the dual space [math]\displaystyle{ X^\star }[/math]), then [math]\displaystyle{ \langle u, v \rangle \leq f^\star(u) + f(v). }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ \langle \cdot , \cdot \rangle : X^\star \times X \to \Reals }[/math] is the dual pairing.

Examples

The convex conjugate of [math]\displaystyle{ f(a) = a^p / p }[/math] is [math]\displaystyle{ g(b) = b^q / q }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ q }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ \tfrac{1}{p} + \tfrac{1}{q} = 1, }[/math] and thus Young's inequality for conjugate Hölder exponents mentioned above is a special case.

The Legendre transform of [math]\displaystyle{ f(a) = e^a - 1 }[/math] is [math]\displaystyle{ g(b) = 1 - b + b \ln b }[/math], hence [math]\displaystyle{ a b \leq e^a - b + b \ln b }[/math] for all non-negative [math]\displaystyle{ a }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ b. }[/math] This estimate is useful in large deviations theory under exponential moment conditions, because [math]\displaystyle{ b \ln b }[/math] appears in the definition of relative entropy, which is the rate function in Sanov's theorem.

See also

- Convex conjugate – Generalization of the Legendre transformation

- Integral of inverse functions – Mathematical theorem, used in calculus

- Legendre transformation – Mathematical transformation

- Young's convolution inequality

Notes

- ↑ Young, W. H. (1912), "On classes of summable functions and their Fourier series", Proceedings of the Royal Society A 87 (594): 225–229, doi:10.1098/rspa.1912.0076, Bibcode: 1912RSPSA..87..225Y

- ↑ Pearse, Erin. "Math 209D - Real Analysis Summer Preparatory Seminar Lecture Notes". https://pi.math.cornell.edu/~erin/analysis/lectures.pdf.

- ↑ Bahouri, Chemin & Danchin 2011.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Jarchow 1981, pp. 47-55.

- ↑ Tisdell, Chris (2013), The Peter Paul Inequality, YouTube video on Dr Chris Tisdell's YouTube channel, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C_bjbjTzHP4,

- ↑ T. Ando (1995). "Matrix Young Inequalities". in Huijsmans, C. B.; Kaashoek, M. A.; Luxemburg, W. A. J. et al.. Operator Theory in Function Spaces and Banach Lattices. Springer. pp. 33–38. ISBN 978-3-0348-9076-2.

- ↑ Hardy, G. H.; Littlewood, J. E.; Pólya, G. (1952) [1934], Inequalities, Cambridge Mathematical Library (2nd ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-05206-8, http://www.cambridge.org/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=9780521358804, Chapter 4.8

- ↑ Henstock, Ralph (1988), Lectures on the Theory of Integration, Series in Real Analysis Volume I, Singapore, New Jersey: World Scientific, ISBN 9971-5-0450-2, https://archive.org/details/lecturesontheory0000hens, Theorem 2.9

- ↑ Mitroi, F. C., & Niculescu, C. P. (2011). An extension of Young's inequality. In Abstract and Applied Analysis (Vol. 2011). Hindawi.

References

- Jarchow, Hans (1981). Locally convex spaces. Stuttgart: B.G. Teubner. ISBN 978-3-519-02224-4. OCLC 8210342.

- Template:Bahouri Chemin Danchin Fourier Analysis and Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations 2011

External links

- Young's Inequality at PlanetMath

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Young's Inequality". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/YoungsInequality.html.

|