Partial differential equation

This article includes a list of general references, but it remains largely unverified because it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

| Differential equations |

|---|

|

| Classification |

| Solution |

In mathematics, a partial differential equation (PDE) is an equation which involves a multivariable function and one or more of its partial derivatives.

The function is often thought of as an "unknown" that solves the equation, similar to how x is thought of as an unknown number solving, e.g., an algebraic equation like x2 − 3x + 2 = 0. However, it is usually impossible to write down explicit formulae for solutions of partial differential equations. There is correspondingly a vast amount of modern mathematical and scientific research on methods to numerically approximate solutions of certain partial differential equations using computers. Partial differential equations also occupy a large sector of pure mathematical research, in which the usual questions are, broadly speaking, on the identification of general qualitative features of solutions of various partial differential equations, such as existence, uniqueness, regularity and stability.[1] Among the many open questions are the existence and smoothness of solutions to the Navier–Stokes equations, named as one of the Millennium Prize Problems in 2000.

Partial differential equations are ubiquitous in mathematically oriented scientific fields, such as physics and engineering. For instance, they are foundational in the modern scientific understanding of sound, heat, diffusion, electrostatics, electrodynamics, thermodynamics, fluid dynamics, elasticity, general relativity, and quantum mechanics (Schrödinger equation, Pauli equation etc.). They also arise from many purely mathematical considerations, such as differential geometry and the calculus of variations; among other notable applications, they are the fundamental tool in the proof of the Poincaré conjecture from geometric topology.

Partly due to this variety of sources, there is a wide spectrum of different types of partial differential equations, where the meaning of a solution depends on the context of the problem, and methods have been developed for dealing with many of the individual equations which arise. As such, it is usually acknowledged that there is no "universal theory" of partial differential equations, with specialist knowledge being somewhat divided between several essentially distinct subfields.[2]

Ordinary differential equations can be viewed as a subclass of partial differential equations, corresponding to functions of a single variable. Stochastic partial differential equations and nonlocal equations are, as of 2020, particularly widely studied extensions of the "PDE" notion. More classical topics, on which there is still much active research, include elliptic and parabolic partial differential equations, fluid mechanics, Boltzmann equations, and dispersive partial differential equations.[3]

Introduction

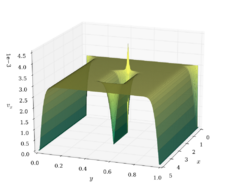

A function u(x, y, z) of three variables is "harmonic" or "a solution of the Laplace equation" if it satisfies the condition Such functions were widely studied in the 19th century due to their relevance for classical mechanics, for example the equilibrium temperature distribution of a homogeneous solid is a harmonic function. If explicitly given a function, it is usually a matter of straightforward computation to check whether or not it is harmonic. For instance and are both harmonic while is not. It may be surprising that the two examples of harmonic functions are of such strikingly different form. This is a reflection of the fact that they are not, in any immediate way, special cases of a "general solution formula" of the Laplace equation. This is in striking contrast to the case of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) roughly similar to the Laplace equation, with the aim of many introductory textbooks being to find algorithms leading to general solution formulas. For the Laplace equation, as for a large number of partial differential equations, such solution formulas fail to exist.

The nature of this failure can be seen more concretely in the case of the following PDE: for a function v(x, y) of two variables, consider the equation It can be directly checked that any function v of the form v(x, y) = f(x) + g(y), for any single-variable functions f and g whatsoever, will satisfy this condition. This is far beyond the choices available in ODE solution formulas, which typically allow the free choice of some numbers. In the study of PDEs, one generally has the free choice of functions.

The nature of this choice varies from PDE to PDE. To understand it for any given equation, existence and uniqueness theorems are usually important organizational principles. In many introductory textbooks, the role of existence and uniqueness theorems for ODE can be somewhat opaque; the existence half is usually unnecessary, since one can directly check any proposed solution formula, while the uniqueness half is often only present in the background in order to ensure that a proposed solution formula is as general as possible. By contrast, for PDE, existence and uniqueness theorems are often the only means by which one can navigate through the plethora of different solutions at hand. For this reason, they are also fundamental when carrying out a purely numerical simulation, as one must have an understanding of what data is to be prescribed by the user and what is to be left to the computer to calculate.

To discuss such existence and uniqueness theorems, it is necessary to be precise about the domain of the "unknown function". Otherwise, speaking only in terms such as "a function of two variables", it is impossible to meaningfully formulate the results. That is, the domain of the unknown function must be regarded as part of the structure of the PDE itself.

The following provides two classic examples of such existence and uniqueness theorems. Even though the two PDE in question are so similar, there is a striking difference in behavior: for the first PDE, one has the free prescription of a single function, while for the second PDE, one has the free prescription of two functions.

- Let B denote the unit-radius disk around the origin in the plane. For any continuous function U on the unit circle, there is exactly one function u on B such that and whose restriction to the unit circle is given by U.

- For any functions f and g on the real line R, there is exactly one function u on R × (−1, 1) such that and with u(x, 0) = f(x) and ∂u/∂y(x, 0) = g(x) for all values of x.

Even more phenomena are possible. For instance, the following PDE, arising naturally in the field of differential geometry, illustrates an example where there is a simple and completely explicit solution formula, but with the free choice of only three numbers and not even one function.

- If u is a function on R2 with then there are numbers a, b, and c with u(x, y) = ax + by + c.

In contrast to the earlier examples, this PDE is nonlinear, owing to the square roots and the squares. A linear PDE is one such that, if it is homogeneous, the sum of any two solutions is also a solution, and any constant multiple of any solution is also a solution.

Definition

A partial differential equation is an equation that involves an unknown function of variables and (some of) its partial derivatives.[4] That is, for the unknown function of variables belonging to the open subset of , the -order partial differential equation is defined as where and is the partial derivative operator.

Notation

When writing PDEs, it is common to denote partial derivatives using subscripts. For example: In the general situation that u is a function of n variables, then ui denotes the first partial derivative relative to the i-th input, uij denotes the second partial derivative relative to the i-th and j-th inputs, and so on.

The Greek letter Δ denotes the Laplace operator; if u is a function of n variables, then In the physics literature, the Laplace operator is often denoted by ∇2; in the mathematics literature, ∇2u may also denote the Hessian matrix of u.

Classification

Linear and nonlinear equations

A PDE is called linear if it is linear in the unknown and its derivatives. For example, for a function u of x and y, a second order linear PDE is of the form where ai and f are functions of the independent variables x and y only. (Often the mixed-partial derivatives uxy and uyx will be equated, but this is not required for the discussion of linearity.) If the ai are constants (independent of x and y) then the PDE is called linear with constant coefficients. If f is zero everywhere then the linear PDE is homogeneous, otherwise it is inhomogeneous. (This is separate from asymptotic homogenization, which studies the effects of high-frequency oscillations in the coefficients upon solutions to PDEs.)

Nearest to linear PDEs are semi-linear PDEs, where only the highest order derivatives appear as linear terms, with coefficients that are functions of the independent variables. The lower order derivatives and the unknown function may appear arbitrarily. For example, a general second order semi-linear PDE in two variables is

In a quasilinear PDE the highest order derivatives likewise appear only as linear terms, but with coefficients possibly functions of the unknown and lower-order derivatives: Many of the fundamental PDEs in physics are quasilinear, such as the Einstein equations of general relativity and the Navier–Stokes equations describing fluid motion.

A PDE without any linearity properties is called fully nonlinear, and possesses nonlinearities on one or more of the highest-order derivatives. An example is the Monge–Ampère equation, which arises in differential geometry.[5]

Second order equations

The elliptic/parabolic/hyperbolic classification provides a guide to appropriate initial- and boundary conditions and to the smoothness of the solutions. Assuming uxy = uyx, the general linear second-order PDE in two independent variables has the form where the coefficients A, B, C... may depend upon x and y. If A2 + B2 + C2 > 0 over a region of the xy-plane, the PDE is second-order in that region. This form is analogous to the equation for a conic section:

More precisely, replacing ∂x by X, and likewise for other variables (formally this is done by a Fourier transform), converts a constant-coefficient PDE into a polynomial of the same degree, with the terms of the highest degree (a homogeneous polynomial, here a quadratic form) being most significant for the classification.

Just as one classifies conic sections and quadratic forms into parabolic, hyperbolic, and elliptic based on the discriminant B2 − 4AC, the same can be done for a second-order PDE at a given point. However, the discriminant in a PDE is given by B2 − AC due to the convention of the xy term being 2B rather than B; formally, the discriminant (of the associated quadratic form) is (2B)2 − 4AC = 4(B2 − AC), with the factor of 4 dropped for simplicity.

- B2 − AC < 0 (elliptic partial differential equation): Solutions of elliptic PDEs are as smooth as the coefficients allow, within the interior of the region where the equation and solutions are defined. For example, solutions of Laplace's equation are analytic within the domain where they are defined, but solutions may assume boundary values that are not smooth. The motion of a fluid at subsonic speeds can be approximated with elliptic PDEs, and the Euler–Tricomi equation is elliptic where x < 0. By change of variables, the equation can always be expressed in the form: where x and y correspond to changed variables. This justifies Laplace equation as an example of this type.[6]

- B2 − AC = 0 (parabolic partial differential equation): Equations that are parabolic at every point can be transformed into a form analogous to the heat equation by a change of independent variables. Solutions smooth out as the transformed time variable increases. The Euler–Tricomi equation has parabolic type on the line where x = 0. By change of variables, the equation can always be expressed in the form: where x correspond to changed variables. This justifies heat equation, which are of form , as an example of this type.[6]

- B2 − AC > 0 (hyperbolic partial differential equation): hyperbolic equations retain any discontinuities of functions or derivatives in the initial data. An example is the wave equation. The motion of a fluid at supersonic speeds can be approximated with hyperbolic PDEs, and the Euler–Tricomi equation is hyperbolic where x > 0. By change of variables, the equation can always be expressed in the form: where x and y correspond to changed variables. This justifies wave equation as an example of this type.[6]

If there are n independent variables x1, x2 , …, xn, a general linear partial differential equation of second order has the form

The classification depends upon the signature of the eigenvalues of the coefficient matrix ai,j.

- Elliptic: the eigenvalues are all positive or all negative.

- Parabolic: the eigenvalues are all positive or all negative, except one that is zero.

- Hyperbolic: there is only one negative eigenvalue and all the rest are positive, or there is only one positive eigenvalue and all the rest are negative.

- Ultrahyperbolic: there is more than one positive eigenvalue and more than one negative eigenvalue, and there are no zero eigenvalues.[7]

The theory of elliptic, parabolic, and hyperbolic equations have been studied for centuries, largely centered around or based upon the standard examples of the Laplace equation, the heat equation, and the wave equation.

However, the classification only depends on linearity of the second-order terms and is therefore applicable to semi- and quasilinear PDEs as well. The basic types also extend to hybrids such as the Euler–Tricomi equation; varying from elliptic to hyperbolic for different regions of the domain, as well as higher-order PDEs, but such knowledge is more specialized.

Systems of first-order equations and characteristic surfaces

The classification of partial differential equations can be extended to systems of first-order equations, where the unknown u is now a vector with m components, and the coefficient matrices Aν are m by m matrices for ν = 1, 2, …, n. The partial differential equation takes the form where the coefficient matrices Aν and the vector B may depend upon x and u. If a hypersurface S is given in the implicit form where φ has a non-zero gradient, then S is a characteristic surface for the operator L at a given point if the characteristic form vanishes:

The geometric interpretation of this condition is as follows: if data for u are prescribed on the surface S, then it may be possible to determine the normal derivative of u on S from the differential equation. If the data on S and the differential equation determine the normal derivative of u on S, then S is non-characteristic. If the data on S and the differential equation do not determine the normal derivative of u on S, then the surface is characteristic, and the differential equation restricts the data on S: the differential equation is internal to S.

- A first-order system Lu = 0 is elliptic if no surface is characteristic for L: the values of u on S and the differential equation always determine the normal derivative of u on S.

- A first-order system is hyperbolic at a point if there is a spacelike surface S with normal ξ at that point. This means that, given any non-trivial vector η orthogonal to ξ, and a scalar multiplier λ, the equation Q(λξ + η) = 0 has m real roots λ1, λ2, …, λm. The system is strictly hyperbolic if these roots are always distinct. The geometrical interpretation of this condition is as follows: the characteristic form Q(ζ) = 0 defines a cone (the normal cone) with homogeneous coordinates ζ. In the hyperbolic case, this cone has nm sheets, and the axis ζ = λξ runs inside these sheets: it does not intersect any of them. But when displaced from the origin by η, this axis intersects every sheet. In the elliptic case, the normal cone has no real sheets.

Analytical solutions

Separation of variables

Linear PDEs can be reduced to systems of ordinary differential equations by the important technique of separation of variables. This technique rests on a feature of solutions to differential equations: if one can find any solution that solves the equation and satisfies the boundary conditions, then it is the solution (this also applies to ODEs). We assume as an ansatz that the dependence of a solution on the parameters space and time can be written as a product of terms that each depend on a single parameter, and then see if this can be made to solve the problem.[8]

In the method of separation of variables, one reduces a PDE to a PDE in fewer variables, which is an ordinary differential equation if in one variable – these are in turn easier to solve.

This is possible for simple PDEs, which are called separable partial differential equations, and the domain is generally a rectangle (a product of intervals). Separable PDEs correspond to diagonal matrices – thinking of "the value for fixed x" as a coordinate, each coordinate can be understood separately.

This generalizes to the method of characteristics, and is also used in integral transforms.

Method of characteristics

The characteristic surface in n = 2-dimensional space is called a characteristic curve.[9] In special cases, one can find characteristic curves on which the first-order PDE reduces to an ODE – changing coordinates in the domain to straighten these curves allows separation of variables, and is called the method of characteristics.

More generally, applying the method to first-order PDEs in higher dimensions, one may find characteristic surfaces.

Integral transform

An integral transform may transform the PDE to a simpler one, in particular, a separable PDE. This corresponds to diagonalizing an operator.

An important example of this is Fourier analysis, which diagonalizes the heat equation using the eigenbasis of sinusoidal waves.

If the domain is finite or periodic, an infinite sum of solutions such as a Fourier series is appropriate, but an integral of solutions such as a Fourier integral is generally required for infinite domains. The solution for a point source for the heat equation given above is an example of the use of a Fourier integral.

Change of variables

Often a PDE can be reduced to a simpler form with a known solution by a suitable change of variables. For example, the Black–Scholes equation is reducible to the heat equation by the change of variables[10]

Fundamental solution

Inhomogeneous equations can often be solved (for constant coefficient PDEs, always be solved) by finding the fundamental solution (the solution for a point source ), then taking the convolution with the boundary conditions to get the solution.

This is analogous in signal processing to understanding a filter by its impulse response.

Superposition principle

The superposition principle applies to any linear system, including linear systems of PDEs. A common visualization of this concept is the interaction of two waves in phase being combined to result in a greater amplitude, for example sin x + sin x = 2 sin x. The same principle can be observed in PDEs where the solutions may be real or complex and additive. If u1 and u2 are solutions of linear PDE in some function space R, then u = c1u1 + c2u2 with any constants c1 and c2 are also a solution of that PDE in the same function space.

Methods for non-linear equations

There are no generally applicable analytical methods to solve nonlinear PDEs. Still, existence and uniqueness results (such as the Cauchy–Kowalevski theorem) are often possible, as are proofs of important qualitative and quantitative properties of solutions (getting these results is a major part of analysis).

Nevertheless, some techniques can be used for several types of equations. The h-principle is the most powerful method to solve underdetermined equations. The Riquier–Janet theory is an effective method for obtaining information about many analytic overdetermined systems.

The method of characteristics can be used in some very special cases to solve nonlinear partial differential equations.[11]

In some cases, a PDE can be solved via perturbation analysis in which the solution is considered to be a correction to an equation with a known solution. Alternatives are numerical analysis techniques from simple finite difference schemes to the more mature multigrid and finite element methods. Many interesting problems in science and engineering are solved in this way using computers, sometimes high performance supercomputers.

Lie group method

From 1870 Sophus Lie's work put the theory of differential equations on a more satisfactory foundation. He showed that the integration theories of the older mathematicians can, by the introduction of what are now called Lie groups, be referred, to a common source; and that ordinary differential equations which admit the same infinitesimal transformations present comparable difficulties of integration. He also emphasized the subject of transformations of contact.

A general approach to solving PDEs uses the symmetry property of differential equations, the continuous infinitesimal transformations of solutions to solutions (Lie theory). Continuous group theory, Lie algebras and differential geometry are used to understand the structure of linear and nonlinear partial differential equations for generating integrable equations, to find its Lax pairs, recursion operators, Bäcklund transform and finally finding exact analytic solutions to the PDE.

Symmetry methods have been recognized to study differential equations arising in mathematics, physics, engineering, and many other disciplines.

Semi-analytical methods

The Adomian decomposition method,[12] the Lyapunov artificial small parameter method, and his homotopy perturbation method are all special cases of the more general homotopy analysis method.[13] These are series expansion methods, and except for the Lyapunov method, are independent of small physical parameters as compared to the well known perturbation theory, thus giving these methods greater flexibility and solution generality.

Numerical solutions

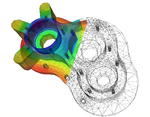

The three most widely used numerical methods to solve PDEs are the finite element method (FEM), finite volume methods (FVM) and finite difference methods (FDM), as well other kind of methods called meshfree methods, which were made to solve problems where the aforementioned methods are limited. The FEM has a prominent position among these methods and especially its exceptionally efficient higher-order version hp-FEM. Other hybrid versions of FEM and Meshfree methods include the generalized finite element method (GFEM), extended finite element method (XFEM), spectral finite element method (SFEM), meshfree finite element method, discontinuous Galerkin finite element method (DGFEM), element-free Galerkin method (EFGM), interpolating element-free Galerkin method (IEFGM), etc.

Finite element method

The finite element method (FEM) (its practical application often known as finite element analysis (FEA)) is a numerical technique for approximating solutions of partial differential equations (PDE) as well as of integral equations using a finite set of functions.[14][15] The solution approach is based either on eliminating the differential equation completely (steady state problems), or rendering the PDE into an approximating system of ordinary differential equations, which are then numerically integrated using standard techniques such as Euler's method, Runge–Kutta, etc.

Finite difference method

Finite-difference methods are numerical methods for approximating the solutions to differential equations using finite difference equations to approximate derivatives.

Finite volume method

Similar to the finite difference method or finite element method, values are calculated at discrete places on a meshed geometry. "Finite volume" refers to the small volume surrounding each node point on a mesh. In the finite volume method, surface integrals in a partial differential equation that contain a divergence term are converted to volume integrals, using the divergence theorem. These terms are then evaluated as fluxes at the surfaces of each finite volume. Because the flux entering a given volume is identical to that leaving the adjacent volume, these methods conserve mass by design.

Neural networks

Weak solutions

Weak solutions are functions that satisfy the PDE, yet in other meanings than regular sense. The meaning for this term may differ with context, and one of the most commonly used definitions is based on the notion of distributions.

An example[19] for the definition of a weak solution is as follows:

Consider the boundary-value problem given by: where denotes a second-order partial differential operator in divergence form.

We say a is a weak solution if for every , which can be derived by a formal integral by parts.

An example for a weak solution is as follows: is a weak solution satisfying in distributional sense, as formally,

Theoretical studies

In pure mathematics, the theoretical studies of PDEs focus on the criteria for a solution to exist and the properties of a solution while finding its formula is often secondary.

Well-posedness

Well-posedness refers to a common schematic package of information about a PDE. To say that a PDE is well-posed, one must have:

- an existence and uniqueness theorem, asserting that by the prescription of some freely chosen functions, one can single out one specific solution of the PDE

- by continuously changing the free choices, one continuously changes the corresponding solution

This is, by the necessity of being applicable to several different PDE, somewhat vague. The requirement of "continuity", in particular, is ambiguous, since there are usually many inequivalent means by which it can be rigorously defined. It is, however, somewhat unusual to study a PDE without specifying a way in which it is well-posed.

Regularity

Regularity refers to the integrability and differentiability of weak solutions, which can often be represented by Sobolev spaces.

This problem arise due to the difficulty in searching for classical solutions. Researchers often tend to find weak solutions at first and then find out whether it is smooth enough to be qualified as a classical solution.

Results from functional analysis are often used in this field of study.

See also

Some common PDEs

- Acoustic wave equation

- Burgers' equation

- Continuity equation

- Heat equation

- Helmholtz equation

- Klein–Gordon equation

- Jacobi equation

- Lagrange equation

- Lorenz equation

- Laplace's equation

- Maxwell's equations

- Navier-Stokes equation

- Poisson's equation

- Reaction–diffusion system

- Schrödinger equation

- Wave equation

Types of boundary conditions

Various topics

- Jet bundle

- Laplace transform applied to differential equations

- List of dynamical systems and differential equations topics

- Matrix differential equation

- Numerical partial differential equations

- Partial differential algebraic equation

- Recurrence relation

- Stochastic processes and boundary value problems

Notes

- ↑ "Regularity and singularities in elliptic PDE's: beyond monotonicity formulas | EllipticPDE Project | Fact Sheet | H2020" (in en). https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/801867.

- ↑ Klainerman, Sergiu (2010). "PDE as a Unified Subject". in Alon, N.; Bourgain, J.; Connes, A. et al.. Visions in Mathematics. Modern Birkhäuser Classics. Basel: Birkhäuser. pp. 279–315. doi:10.1007/978-3-0346-0422-2_10. ISBN 978-3-0346-0421-5.

- ↑ Erdoğan, M. Burak; Tzirakis, Nikolaos (2016). Dispersive Partial Differential Equations: Wellposedness and Applications. London Mathematical Society Student Texts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-14904-5. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/dispersive-partial-differential-equations/2DC65286BA080B54EB659E42A553CA88.

- ↑ Evans 1998, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Klainerman, Sergiu (2008), Partial Differential Equations, Princeton University Press, pp. 455–483

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Levandosky, Julie. "Classification of Second-Order Equations". https://web.stanford.edu/class/math220a/handouts/secondorder.pdf.

- ↑ Courant and Hilbert (1962), p.182.

- ↑ Gershenfeld, Neil (2000). The nature of mathematical modeling (Reprinted (with corr.) ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 27. ISBN 0521570956. https://archive.org/details/naturemathematic00gers_334.

- ↑ Zachmanoglou & Thoe 1986, pp. 115–116.

- ↑ Wilmott, Paul; Howison, Sam; Dewynne, Jeff (1995). The Mathematics of Financial Derivatives. Cambridge University Press. pp. 76–81. ISBN 0-521-49789-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=VYVhnC3fIVEC&pg=PA76.

- ↑ Logan, J. David (1994). "First Order Equations and Characteristics". An Introduction to Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations. New York: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 51–79. ISBN 0-471-59916-6.

- ↑ Adomian, G. (1994). Solving Frontier problems of Physics: The decomposition method. Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 9789401582896. https://books.google.com/books?id=UKPqCAAAQBAJ&q=%22partial+differential%22.

- ↑ Liao, S. J. (2003). Beyond Perturbation: Introduction to the Homotopy Analysis Method. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/ CRC Press. ISBN 1-58488-407-X.

- ↑ Solin, P. (2005). Partial Differential Equations and the Finite Element Method. Hoboken, New Jersey: J. Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-72070-4.

- ↑ Solin, P.; Segeth, K.; Dolezel, I. (2003). Higher-Order Finite Element Methods. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC Press. ISBN 1-58488-438-X.

- ↑ Raissi, M.; Perdikaris, P.; Karniadakis, G. E. (2019-02-01). "Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations" (in en). Journal of Computational Physics 378: 686–707. doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2018.10.045. ISSN 0021-9991. Bibcode: 2019JCoPh.378..686R. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0021999118307125.

- ↑ Mao, Zhiping; Jagtap, Ameya D.; Karniadakis, George Em (2020-03-01). "Physics-informed neural networks for high-speed flows" (in en). Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 360: 112789. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2019.112789. ISSN 0045-7825. Bibcode: 2020CMAME.360k2789M. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0045782519306814.

- ↑ Raissi, Maziar; Yazdani, Alireza; Karniadakis, George Em (2020-02-28). "Hidden fluid mechanics: Learning velocity and pressure fields from flow visualizations". Science 367 (6481): 1026–1030. doi:10.1126/science.aaw4741. PMID 32001523. Bibcode: 2020Sci...367.1026R.

- ↑ Evans 1998, chpt. 6. Second-Order Elliptic Equations.

References

- Courant, R.; Hilbert, D. (1962), Methods of Mathematical Physics, II, New York: Wiley-Interscience, ISBN 9783527617241, https://books.google.com/books?id=fcZV4ohrerwC.

- Drábek, Pavel; Holubová, Gabriela (2007). Elements of partial differential equations (Online ed.). Berlin: de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110191240.

- Evans, Lawrence C. (1998). Partial differential equations. Providence (R. I.): American mathematical society. ISBN 0-8218-0772-2. https://math24.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/partial-differential-equations-by-evans.pdf.

- Ibragimov, Nail H. (1993), CRC Handbook of Lie Group Analysis of Differential Equations Vol. 1-3, Providence: CRC-Press, ISBN 0-8493-4488-3.

- John, F. (1982), Partial Differential Equations (4th ed.), New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0-387-90609-6, https://archive.org/details/partialdifferent00john_0.

- Jost, J. (2002), Partial Differential Equations, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0-387-95428-7.

- Olver, P.J. (1995), Equivalence, Invariants and Symmetry, Cambridge Press.

- Petrovskii, I. G. (1967), Partial Differential Equations, Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co..

- Pinchover, Y.; Rubinstein, J. (2005), An Introduction to Partial Differential Equations, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-84886-5.

- Polyanin, A. D. (2002), Handbook of Linear Partial Differential Equations for Engineers and Scientists, Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC Press, ISBN 1-58488-299-9.

- Polyanin, A. D.; Zaitsev, V. F. (2004), Handbook of Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations, Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC Press, ISBN 1-58488-355-3.

- Polyanin, A. D.; Zaitsev, V. F.; Moussiaux, A. (2002), Handbook of First Order Partial Differential Equations, London: Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-415-27267-X.

- Roubíček, T. (2013), Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations with Applications, International Series of Numerical Mathematics, 153 (2nd ed.), Basel, Boston, Berlin: Birkhäuser, doi:10.1007/978-3-0348-0513-1, ISBN 978-3-0348-0512-4, https://cds.cern.ch/record/880983/files/9783764372934_TOC.pdf

- Stephani, H. (1989), MacCallum, M., ed., Differential Equations: Their Solution Using Symmetries, Cambridge University Press.

- Wazwaz, Abdul-Majid (2009). Partial Differential Equations and Solitary Waves Theory. Higher Education Press. ISBN 978-3-642-00251-9.

- Wazwaz, Abdul-Majid (2002). Partial Differential Equations Methods and Applications. A.A. Balkema. ISBN 90-5809-369-7.

- Zwillinger, D. (1997), Handbook of Differential Equations (3rd ed.), Boston: Academic Press, ISBN 0-12-784395-7.

- Gershenfeld, N. (1999), The Nature of Mathematical Modeling (1st ed.), New York: Cambridge University Press, New York, NY, USA, ISBN 0-521-57095-6.

- Krasil'shchik, I.S.; Vinogradov, A.M., Eds. (1999), Symmetries and Conserwation Laws for Differential Equations of Mathematical Physics, American Mathematical Society, Providence, Rhode Island, USA, ISBN 0-8218-0958-X.

- Krasil'shchik, I.S.; Lychagin, V.V.; Vinogradov, A.M. (1986), Geometry of Jet Spaces and Nonlinear Partial Differential Equations, Gordon and Breach Science Publishers, New York, London, Paris, Montreux, Tokyo, ISBN 2-88124-051-8.

- Vinogradov, A.M. (2001), Cohomological Analysis of Partial Differential Equations and Secondary Calculus, American Mathematical Society, Providence, Rhode Island, USA, ISBN 0-8218-2922-X.

- Gustafsson, Bertil (2008). High Order Difference Methods for Time Dependent PDE. Springer Series in Computational Mathematics. 38. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-74993-6. ISBN 978-3-540-74992-9.

- Zachmanoglou, E. C.; Thoe, Dale W. (1986). Introduction to Partial Differential Equations with Applications. New York: Courier Corporation. ISBN 0-486-65251-3.

Further reading

- Cajori, Florian (1928). "The Early History of Partial Differential Equations and of Partial Differentiation and Integration". The American Mathematical Monthly 35 (9): 459–467. doi:10.2307/2298771. http://www.math.harvard.edu/archive/21a_fall_14/exhibits/cajori/cajori.pdf. Retrieved 2016-05-15.

- Nirenberg, Louis (1994). "Partial differential equations in the first half of the century." Development of mathematics 1900–1950 (Luxembourg, 1992), 479–515, Birkhäuser, Basel.

- "Partial Differential Equations in the 20th Century". Advances in Mathematics 135 (1): 76–144. 1998. doi:10.1006/aima.1997.1713.

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Differential equation, partial", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=p/d031920

- Partial Differential Equations: Exact Solutions at EqWorld: The World of Mathematical Equations.

- Partial Differential Equations: Index at EqWorld: The World of Mathematical Equations.

- Partial Differential Equations: Methods at EqWorld: The World of Mathematical Equations.

- Example problems with solutions at exampleproblems.com

- Partial Differential Equations at mathworld.wolfram.com

- Partial Differential Equations with Mathematica

- Partial Differential Equations in Cleve Moler: Numerical Computing with MATLAB

- Partial Differential Equations at nag.com

- Sanderson, Grant (April 21, 2019). "But what is a partial differential equation?". 3Blue1Brown. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ly4S0oi3Yz8&list=PLZHQObOWTQDNPOjrT6KVlfJuKtYTftqH6.

|