Biography:Guru Ram Das

Guru Ram Das | |

|---|---|

ਗੁਰੂ ਰਾਮ ਦਾਸ | |

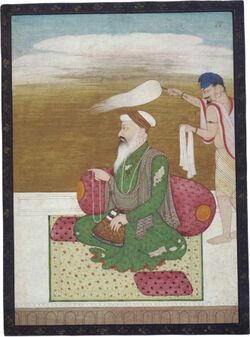

Guru Ram Das (seated) being fanned by a fly-whisk attendant, family atelier of Nainsukh of Guler, c. 1800 | |

| Other names |

|

| Personal | |

| Born | Jetha Mal Sodhi 24 September 1534[1] Chuna Mandi, Lahore, Mughal Empire |

| Died | 1 September 1581 (aged 46) Goindwal, Mughal Empire |

| Religion | Sikhism |

| Spouse | Bibi Bhani (m. 1553) |

| Children | 3, including Prithi Chand and Guru Arjan |

| Known for | Founder of Amritsar city[2] |

| Other names |

|

| Signature |  |

| Religious career | |

| Based in | Ramdaspur |

| Predecessor | Guru Amar Das |

| Successor | Guru Arjan |

Guru Ram Das (Gurmukhi: ਗੁਰੂ ਰਾਮ ਦਾਸ, pronunciation: [gʊɾuː ɾaːmᵊ d̯aːsᵊ]; 24 September 1534 – 1 September 1581) was the fourth of the ten Sikh gurus.[2][3] He was born in a family based in Lahore.[3][1] His birth name was Jetha, and he was orphaned at age seven; he thereafter grew up with his maternal grandmother in a village.[3]

At age 12, Bhai Jetha and his grandmother moved to Goindval, where they met Guru Amar Das.[3] The boy thereafter accepted Guru Amar Das as his mentor and served him. The daughter of Guru Amar Das married Bhai Jetha, and he thus became part of Guru Amar Das's family. As with the first two Gurus of Sikhism, Guru Amar Das instead of choosing his own sons, chose Bhai Jetha, owing to Bhai Jetha's exemplary service, selfless devotion and unquestioning obedience to the commands of the Guru, as his successor and renamed him as Ram Das or "servant of God."[3][1][4]

Guru Ram Das became the Guru of Sikhism in 1574 and served as the 4th guru until he gave up his body to transcend the material world in 1581.[5] He faced hostility from the sons of Guru Amar Das, and shifted his official base to lands identified by Guru Amar Das as Guru-ka-Chak.[3] This newly founded town was eponymous Ramdaspur, later to evolve and be renamed as Amritsar – the holiest city of Sikhism.[6][7] He is also remembered in the Sikh tradition for expanding the manji organization for clerical appointments and donation collections to theologically and economically support the Sikh movement.[3] He appointed his own son as his successor, and unlike the first four Gurus who were not related through descent, the fifth through tenth Sikh Gurus were the direct descendants of Guru Ram Das.[7][8]

Early life

Family background and life in Lahore

Bhai Jetha was born in the morning of 24 September 1534 in a family belonging to the Sodhi gotra (clan) of the Khatri caste in Chuna Mandi, Lahore.[9][10][11] His father was Hari Das and his mother was Mata Anup Devi (also known later-on as Anup Kaur or Daya Kaur[10][11]), both of whom were highly religious.[12][10][11] His paternal grandfather was Thakur Das, who was well-known and worked as a shopkeeper in Chuna Mandi, his paternal grandmother was named Jaswanti, and his great-grandfather was Gurdial Sodhi.[12][10][11] His father, Hari Das, had inherited the shopkeeper occupation from his own father.[10] His parents had been married for a period of around twelve years before they gave birth to Ram Das.[11] He was named "Jetha" because he was the eldest child of his siblings.[12] Some sources state his actual birthname was still 'Ram Das' and that 'Jetha' was just a nickname he acquired.[10][11] He had a brother named Hardyal and a sister named Ram Dasi.[10] Both of Jetha's parents died when he was aged around seven.[12][10][11] After his parents' deaths, he went into the care of his maternal grandmother.[10][11]

Life as an orphan in Basarke

His grandmother took him to her village, Basarke, Jetha lived there for five years.[1][13][12] Basarke also happened to coincidentally be the ancestral village of Guru Amar Das.[11] Jetha's grandmother was a destitute lady who faced troubles raising the three orphaned siblings.[10] Jetha sold boiled grams, boiled black chickpeas (known as ghugaian), and boiled wheat in the local market square of Basarke to earn a living at the age of around nine.[10][11] Jetha would sometimes encounter holy-men whilst he was out-and-about working who he would share his provisions of food produce with free-of-cost, being reprimanded by his grandmother for doing so.[10] It is said that when Amar Das just so happened to be visiting Basarke, he came across the young Jetha.[10] Traits that Amar Das saw in the young Jetha that made him take a liking to him was that he was supporting his elderly grandmother at a young age and he lived a deeply spiritual life.[10] Amar Das would meet with Jetha many times in this manner.[10] However, one time when Amar Das visiting Basarke, he would leave next for Khadur, where his guru, Angad, was based out of.[10] Jetha decided to also make the journey to Khadur.[10]

Staying in Khadur and Goindwal

Amar Das was then living at Khadur at the sangat (religious congregation) of Guru Angad. Jetha went to Khadur in 1546, attended Guru Angad's sangats, and developed great liking for the Guru and Amar Das.[10] He frequently partook in the local langar of Khadur.[10] Bhai Jetha spent a lot of his time hawking and selling baklian (boiled corn) when he stayed at Khadur to generate an income for himself.[12][10] Guru Amar Das eventually visited Basarke again and returned to Goindwal with Bhai Jetha in his company.[12][10] When Guru Amar Das settled at Goindwal in 1552, Jetha also moved to the new township, and spent most of his time at the guru's durbar (court).[12] One of the activities that Jetha was responsible for at Goindwal was ensuring the utensils used in the langar were cleaned, which he cleaned himself.[10] He was also assigned the role of serving drinking water in the langar, and had been given additional duties related to the pangat.[10] Additionally, he helped with digging work to assist with the construction of a water tank.[10] He spent time with Guru Amar Das by accompanying him on religious pilgrimages.[12] Under the patronage of Guru Amar Das, Bhai Jetha was educated in North Indian musical tradition.[14]

Representing the Sikhs at the Mughal court

Before becoming Guru, Jetha represented Guru Amar Das in the Mughal court.[15][11] Local residents (particularly Brahmins) living around Goindwal lodged a complaint to the local Mughal government of Lahore about the activities of the Sikhs at Goindwal.[11] The Brahmin residents complained and protested about the Sikh tradition of operating a free community kitchen (langar), discarding traditional beliefs and practices, and not recognizing caste divisions and hierarchies.[11] Guru Amar Das sent Jetha to be his representative at the Mughal court on his behalf.[11] Jetha met with emperor Akbar and simply put forth the argument that in the eyes of the divine, all of humankind is equal.[11] This response is said to have pleased Akbar, who dismissed any complaints made against the Sikhs.[11]

Marriage

In 1553, he married Bibi Bhani, the younger daughter of Amar Das. Jetha was selected personally by Guru Amar Das' wife, Mata Mansa Devi, as the best match for their daughter Bhani due to his devoted and pious personality.[10][11] They had three sons: Prithi Chand (1554–1623), Mahadev (1559–1656) and Guru Arjan (1563–1606).[3] Jetha's immediate family often protested the work he was doing at the house of his in-laws.[10]

Test to become a worthy successor

Guru Amar Das designed a test to decide which of his two son-in-laws, Ramo and Jetha, was worthy of being his successor.[10] He requested them to build a platform which befitting for the Sikh guru to be seated upon.[10] Ramo built four platforms but none were to the liking of Guru Amar Das so Ramo gave-up.[10] Jetha constructed seven platforms of his own but also failed to satisfy the Guru, but instead of giving up like Ramo, he submitted himself humbly to the Guru and stated he would continue trying to please him by building a worthy platform for his master, it was this action that made Guru Amar Das decide he was worthy for the guruship mantle.[10] Thus, Jetha was selected as the next Sikh guru and would become known as Guru Ram Das.[10]

Guruship

Jetha become guru on 30 August 1574,[16] became known as Guru Ram Das, and held the office for seven years.

He was the first of Guru Nanak's successors to rekindle ties with Sri Chand, Nanak's son, after a long period of strained relations between mainstream Sikhs and the Udasis.[10] Sri Chand paid Guru Ram Das a visit in Amritsar, where he was lavishly received by the Guru on the outskirts of the city.[10] When Sri Chand made a comment about Guru Ram Das' long beard, the Guru stated the beard is useful for wiping the feet of saints like him, and got-up to actually wipe the feet of Sri Chand with his beard.[10] Sri Chand then realized why Guru Ram Das was worthy of occupying his father's spiritual seat after witnessing this action.[10]

The Guru was eventually joined by Bhai Gurdas, a familial relative of his predecessor whom was well-educated in religious, linguistic, and literary pursuits.[10] Bhai Gurdas helped advance the Sikh cause during the time of Guru Ram Das.[10]

At some point, local Lahori Sikhs paid a visit to the Guru to engage in Kar Seva voluntary work and petitioned him to find time to pay a visit to his birth city.[10] The Guru visited the city, he was warmly welcomed and gained more followers in the process.[10]

Founding of Amritsar and initiation of construction of the Harmandir Sahib complex

Guru Ram Das is credited with founding and building the city of Amritsar in the Sikh tradition.[6][7][10] Two versions of stories exist regarding the land where Guru Ram Das settled. In one based on a Gazetteer record, the land was purchased with Sikh donations, for 700 rupees from the owners of the village of Tung.[1][17]

According to the Sikh historical records, the site was chosen by Guru Amar Das and called Guru Da Chakk, after he had asked Guru Ram Das to find land to start a new town with a man made pool as its central point.[1][18][19] After his coronation in 1574, and the hostile opposition he faced from the sons of Guru Amar Das,[3] Guru Ram Das founded the town named after him as "Ramdaspur". He started by completing the pool, and building his new official Guru centre and home next to it. He invited merchants and artisans from other parts of India to settle into the new town with him.[1] The town expanded during the time of Guru Arjan financed by donations and constructed by voluntary work. The town grew to become the city of Amritsar, and the pool area grew into a temple complex after his son built the Gurdwara Harmandir Sahib, and installed the scripture of Sikhism inside the new gurdwara in 1604.[7]

The construction activity between 1574 and 1604 is described in Mahima Prakash Vartak, a semi-historical Sikh hagiography text likely composed in 1741, and the earliest known document dealing with the lives of all the ten Gurus.[20]

As per the instruction of his predecessor, Guru Ram Das also constructed two man-made pools of holy water (known as sarovars) in Guru-Da-Chak, with their names being Ramdas Sarovar and Amritsar Sarovar.[10]

Literary works

Guru Ram Das composed 638 hymns, or about ten percent of hymns in the Guru Granth Sahib. He was a celebrated poet, and composed his work in 30 ancient ragas of Indian classical music.[21]

These cover a range of topics:

One who calls himself to be a disciple of the Guru should rise before dawn and meditate on the Lord's Name. During the early hours, he should rise and bathe, cleansing his soul in a tank of nectar [water], while he repeats the Name the Guru has spoken to him. By this procedure he truly washes away the sins of his soul. – GGS 305 (partial)

The Name of God fills my heart with joy. My great fortune is to meditate on God's name. The miracle of God's name is attained through the perfect Guru, but only a rare soul walks in the light of the Guru's wisdom. – GGS 94 (partial)

O man! The poison of pride is killing you, blinding you to God. Your body, the colour of gold, has been scarred and discoloured by selfishness. Illusions of grandeur turn black, but the ego-maniac is attached to them. – GGS 776 (partial)—Guru Granth Sahib, Translated by G. S. Mansukhani[1]

His compositions continue to be sung daily in Harmandir Sahib (Golden temple) of Sikhism.[21]

Wedding hymn

Guru Ram Das, along with Guru Amar Das, are credited with various parts of the Anand and Laavan composition in Suhi mode. It is a part of the ritual of four clockwise circumambulation of the Sikh scripture by the bride and groom to solemnize the marriage in Sikh tradition.[21][22] This was intermittently used, and its use lapsed in late 18th century. However, sometime in 19th or 20th century by conflicting accounts, the composition of Guru Ram Das came back in use along with Anand Karaj ceremony, replacing the Hindu ritual of circumambulation around the fire. The composition of Guru Ram emerged to be one of the bases of the British colonial era Anand Marriage Act of 1909.[22]

The wedding hymn was composed by Guru Ram Das for his own daughter's wedding. The first stanza of the Laavan hymn by Guru Ram Das refers to the duties of the householder's life to accept the Guru's word as guide, remember the Divine Name. The second verse and circle reminds the singular One is encountered everywhere and in the depths of the self. The third speaks of the Divine Love. The fourth reminds that the union of the two is the union of the individual with the Infinite.[23]

Masand system

While Guru Amar Das introduced the manji system of religious organization, Guru Ram Das extended it with adding the masand institution.[10] After a suggestion by Baba Buddha to venture into new potentials for generating funds, Guru Ram Das came-up with the Masand missionary system.[10] The masand were Sikh community leaders and preachers who lived far from the Guru in distant parts of the subcontinent and beyond, but acted to lead the distant congregations, their mutual interactions and collect revenue for Sikh activities and Gurudwara building.[3][24][10] This institutional organization famously helped grow Sikhism in the decades that followed, but became infamous in the era of later Gurus, for its corruption and its misuse in financing rival Sikh movements in times of succession disputes.[24][25] However, the early Masand leaders tended to be hardworking and committed Sikhs.[10]

Selection of a successor

The Guru's three sons had distinctive roles and personality traits: Prithi Chand was responsible for ensuring the smooth operation of the langar, keeping records, and overseeing appropriate accommodation for visitors; Mahadev was a deeply spiritual individual who had no interest in worldly affairs and preferred to be by himself; and Arjan Dev was the youngest but deeply pious and viewed his father truly as a spiritual teacher and role-model to emulate.[10]

Guru Ram Das had a cousin named Sehari Mal who visited the Guru from Lahore and invited him to his son's marriage ceremony.[10] However, the Guru was busy and would be unable to attend the marriage and thus requested his eldest son Prithi Chand go on his behalf to represent him.[10] Prithi refused to go as he believed that being separated from the Guru lessened his chances of being selected as his successor.[10] However, Prithi used the excuse that he was too engrossed and concerned with the operation of the langar, fund acquisition, and other responsibilities, to be able to go to Lahore for the marriage ceremony.[10] Mahadev was not interested in worldly occasions like marriage events and declined to go.[10] Arjan Dev on the other hand willingly accepted the request to represent his father at Lahore.[10] Arjan Dev stayed at Lahore for a few days waiting for a message from his father approving of his return but the message never came.[10] He eventually waited for around a month and still received no word from his father.[10] Arjan authored two letters written poetically to his father to inquire about the situation but still received no reply.[10] He then sent a third letter but specifically ordered the courier to hand the letter over to the Guru himself and not let it pass into anyone else's hands.[10] This third letter was successfully received by the Guru and it was discovered that it was Prithi Chand who had been stealing the letters and preventing their deliverance.[10] The Guru managed to obtain the prior two letters that had gone undelivered due to them being hidden by Prithi.[10]

Guru Ram Das took a great liking to the three letters written in verse by his son Arjan and requested his other sons write poetic letters like them.[10] However, Arjan was thrilled to be reunited with his father and decided to write yet another and fourth letter in verse, which won over the heart of his father and made him decide to select his youngest son Arjan as his worthy successor.[10]

Death and succession

Guru Ram Das died on 1 September 1581, in Goindwal, he nominated his younger son, Arjan Dev, as his successor. The Guru's eldest son Prithi Chand vehemently protested against his father suppression.[10] The second son Mahadev did not press his claim.[10] Prithi Chand used offensive language to his father, and then informed Baba Budhha that his father had acted inappropriately, the guruship was his own right.[10] He vowed that he would remove Guru Arjan, and make himself the Guru.[10] Later Prithi Chand created a rival faction which the Sikhs following Guru Arjan called Minas[26] literally, "scoundrels"), and is alleged to have attempted to assassinate young Hargobind.[27][28] However, alternate competing texts written by the Prithi Chand led Sikh faction to offer a different story, contradict this explanation on Hargobind's life, and present the elder son of Guru Ram Das as devoted to his younger brother Guru Arjan. The competing texts do acknowledge disagreement and describe Prithi Chand as having become the Sahib Guru after the martyrdom of Guru Arjan Dev and disputing the succession of Guru Hargobind, the grandson of Guru Ram Das.[29]

Gallery

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 G.S. Mansukhani. "Ram Das, Guru (1534–1581)". Punjab University Patiala. http://www.learnpunjabi.org/eos/index.aspx.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 William Owen Cole; Piara Singh Sambhi (1995). The Sikhs: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 22–24. ISBN 978-1-898723-13-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=zIC_MgJ5RMUC&pg=PA23.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair (2013). Sikhism: A Guide for the Perplexed. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 38–40. ISBN 978-1-4411-5366-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=Jn_jBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA38.

- ↑ Shakti Pawha Kaur Khalsa (1998). Kundalini Yoga: The Flow of Eternal Power. Penguin. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-399-52420-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=E6ZgJvdMEzYC&pg=PA76.

- ↑ Arvind-pal Singh Mandair (2013). Religion and the Specter of the West: Sikhism, India, Postcoloniality, and the Politics of Translation. Columbia University Press. pp. 251–252. ISBN 978-0-231-51980-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=dzeCy_zL0Q8C&pg=PA251.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 W.H. McLeod (1990). Textual Sources for the Study of Sikhism. University of Chicago Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-0-226-56085-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=7xIT7OMSJ44C&pg=PA28.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Christopher Shackle; Arvind Mandair (2013). Teachings of the Sikh Gurus: Selections from the Sikh Scriptures. Routledge. pp. xv–xvi. ISBN 978-1-136-45101-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=VvoJV8mw0LwC.

- ↑ W. H. McLeod (2009). The A to Z of Sikhism. Scarecrow Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-8108-6344-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=vgixwfeCyDAC&pg=PA86.

- ↑ Fenech, pp. 259–260

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 10.11 10.12 10.13 10.14 10.15 10.16 10.17 10.18 10.19 10.20 10.21 10.22 10.23 10.24 10.25 10.26 10.27 10.28 10.29 10.30 10.31 10.32 10.33 10.34 10.35 10.36 10.37 10.38 10.39 10.40 10.41 10.42 10.43 10.44 10.45 10.46 10.47 10.48 10.49 10.50 10.51 10.52 10.53 10.54 10.55 10.56 10.57 10.58 10.59 10.60 10.61 10.62 10.63 Singh, Prithi Pal (2006). The History of Sikh Gurus. Lotus Press. pp. 54–60. ISBN 9788183820752.

- ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 11.11 11.12 11.13 11.14 11.15 11.16 Singh, Pashaura; Mandair, Arvind-Pal Singh (2023). "Guru Ram Das (1534–1581)". The Sikh World. Routledge Worlds. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780429848384.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 12.8 Jain, Harish C. (2003). The Making of Punjab. Unistar Books. pp. 274–275.

- ↑ Singh, Prithi Pal (2007). The History of Sikh Gurus. Lotus Press. pp. 54. ISBN 978-81-8382-075-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=EhGkVkhUuqoC&pg=PA54.

- ↑ Singh, Pashaura; Mandair, Arvind-Pal Singh (2023). The Sikh World. Routledge Worlds. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780429848384. "Under his [Guru Amar Das] patronage, his son-in-law Ram Das received training in the musical traditions of North India, and his nephew Gurdas Bhalla received his early education in Punjabi, Braj, and Persian languages, including Hindu and Muslim literary traditions at Sultanpur Lodhi."

- ↑ Singh, Kushwant (2004). A history of the Sikhs Volume-1. Oxford University Press. pp. 52. ISBN 978-0-19-567308-1.

- ↑ "Today in History: Guru Ram Das became the fourth Sikh Guru in 1574". Times of India. 30 August 2019. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/videos/news/today-in-history-guru-ram-das-became-the-fourth-sikh-guru-in-1574/videoshow/70893660.cms.

- ↑ Fenech, p. 67

- ↑ Pardeep Singh Arshi (1989). The Golden Temple: history, art, and architecture. Harman. pp. 5–7. ISBN 978-81-85151-25-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=rcmfAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ Fenech, p. 33

- ↑ W.H. McLeod (1990). Textual Sources for the Study of Sikhism. University of Chicago Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-0-226-56085-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=7xIT7OMSJ44C&pg=PA28.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Pashaura Singh; Louis E. Fenech (March 2014). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 399–400. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=8I0NAwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Fenech, pp. 33–34

- ↑ Nikky-Guninder Kaur Singh (2011). Sikhism: An Introduction. I.B.Tauris. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-84885-321-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=e0ZmAXw7ok8C.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Pashaura Singh; Louis E. Fenech (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 44–. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=8I0NAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA44.

- ↑ Madanjit Kaur (2007). Guru Gobind Singh: Historical and Ideological Perspective. Unistar. pp. 251–252. ISBN 978-81-89899-55-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=ZG4MycGdpjAC&pg=PA252.

- ↑ Hari Ram Gupta (1999). The history of the sikh gurus. Munshilal Manoharlal Pvt.Ltd. ISBN 81-215-0165-2.

- ↑ Fenech, p. 39

- ↑ W. H. McLeod (2009). The A to Z of Sikhism. Scarecrow Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-8108-6344-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=vgixwfeCyDAC&pg=PA86.

- ↑ Pashaura Singh; Louis E. Fenech (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 171–172. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=8I0NAwAAQBAJ.

Cited sources

- Fenech, Louis E.; W. H. McLeod (2014). Historical Dictionary of Sikhism. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-3601-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=xajcAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA29.

External links

| Preceded by Guru Amar Das |

Sikh Guru 1 September 1574 – 1 September 1581 |

Succeeded by Guru Arjan |

|