Medicine:Atrophic gastritis

| Atrophic gastritis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Type A gastritis[1] |

| |

| Atrophic gastritis | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

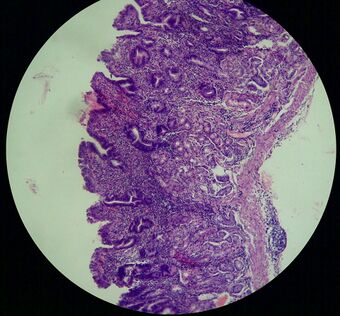

Atrophic gastritis is a process of chronic inflammation of the gastric mucosa of the stomach, leading to a loss of gastric glandular cells and their eventual replacement by intestinal and fibrous tissues. As a result, the stomach's secretion of essential substances such as hydrochloric acid, pepsin, and intrinsic factor is impaired, leading to digestive problems. The most common are vitamin B12 deficiency possibly leading to pernicious anemia; and malabsorption of iron, leading to iron deficiency anaemia.[2] It can be caused by persistent infection with Helicobacter pylori, or can be autoimmune in origin. Those with autoimmune atrophic gastritis (Type A gastritis) are statistically more likely to develop gastric carcinoma, Hashimoto's thyroiditis, and achlorhydria.

Type A gastritis primarily affects the fundus (body) of the stomach and is more common with pernicious anemia.[1] Type B gastritis primarily affects the antrum, and is more common with H. pylori infection.[1]

Signs and symptoms

Some people with atrophic gastritis may be asymptomatic. Symptomatic patients are mostly females and signs of atrophic gastritis are those associated with iron deficiency: fatigue, restless legs syndrome, brittle nails, hair loss, impaired immune function, and impaired wound healing.[3] And other symptoms, such as delayed gastric emptying (80%), reflux symptoms (25%), peripheral neuropathy (25% cases), autonomic abnormalities, and memory loss, are less common and occur in 1%–2% of cases. Psychiatric disorders are also reported, such as mania, depression, obsessive compulsive disorder, psychosis and cognitive impairment.[4]

Although autoimmune atrophic gastritis impairs iron and vitamin B12 absorption, iron deficiency is detected at a younger age than pernicious anemia.[3]

Associated conditions

People with atrophic gastritis are also at increased risk for the development of gastric adenocarcinoma.[5]

Causes

Recent research has shown that autoimmune metaplastic atrophic gastritis (AMAG) is a result of the immune system attacking the parietal cells.[6]

Environmental metaplastic atrophic gastritis (EMAG) is due to environmental factors, such as diet and H. pylori infection. EMAG is typically confined to the body of the stomach. Patients with EMAG are also at increased risk of gastric carcinoma.[citation needed]

Pathophysiology

Autoimmune metaplastic atrophic gastritis (AMAG) is an inherited form of atrophic gastritis characterized by an immune response directed toward parietal cells and intrinsic factor.[6] The presence of serum antibodies to parietal cells and to intrinsic factor are characteristic findings. The autoimmune response subsequently leads to the destruction of parietal cells, which leads to profound Achlorhydria (and elevated gastrin levels). The inadequate production of intrinsic factor also leads to vitamin B12 malabsorption and pernicious anemia. AMAG is typically confined to the gastric body and fundus.[citation needed]

Achlorhydria induces G cell (gastrin-producing) hyperplasia, which leads to hypergastrinemia. Gastrin exerts a trophic effect on enterochromaffin-like cells (ECL cells are responsible for histamine secretion) and is hypothesized to be one mechanism to explain the malignant transformation of ECL cells into carcinoid tumors in AMAG.[citation needed]

Diagnosis

Detection of APCA(Antiparietal cell antibody), anti-intrinsic factor antibody (AIFA) and Helicobacter pylori (HP) antibodies in conjunction with serum gastrin are effective for diagnostic purposes.[7]

Classification

The notion that atrophic gastritis could be classified depending on the level of progress as "closed type" or "open type" was suggested in early studies,[8] but no universally accepted classification exists as of 2017.[7]

Treatment

Supplementation of folic acid in deficient patients can improve the histopathological findings of chronic atrophic gastritis and reduce the incidence of gastric cancer.[9]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Type B gastritis, aging, and Campylobacter pylori". Arch. Intern. Med. 148 (5): 1021–2. May 1988. doi:10.1001/archinte.1988.00380050027005. ISSN 0003-9926. PMID 3365072.

- ↑ "Concomitant alterations in intragastric pH and ascorbic acid concentration in patients with Helicobacter pylori gastritis and associated iron deficiency anaemia". Gut 52 (4): 496–501. April 2003. doi:10.1136/gut.52.4.496. ISSN 0017-5749. PMID 12631657.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Stefanie Kulnigg-Dabsch (2016). "Autoimmune gastritis". Wien Med Wochenschr 166 (13–14): 424–430. doi:10.1007/s10354-016-0515-5. PMID 27671008.

- ↑ Sara Massironi; Alessandra Zilli; Alessandra Elvevi; Pietro Invernizzi (2019). "The changing face of chronic autoimmune atrophic gastritis: an updated comprehensive perspective". Autoimmun. Rev. 18 (3): 215–222. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2018.08.011. PMID 30639639.

- ↑ "Helicobacter pylori evolution during progression from chronic atrophic gastritis to gastric cancer and its impact on gastric stem cells". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 (11): 4358–63. March 2008. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800668105. PMID 18332421. Bibcode: 2008PNAS..105.4358G.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Autoimmune Metaplastic Atrophic Gastritis: Gastritis and Peptic Ulcer Disease: Merck Manual Professional". Merck & Co. http://www.merck.com/mmpe/sec02/ch013/ch013d.html.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Autoimmune atrophic gastritis: current perspectives". Clin Exp Gastroenterol 10: 19–27. 2017. doi:10.2147/CEG.S109123. PMID 28223833.

- ↑ Kimura, K.; Takemoto, T. (2008). "An Endoscopic Recognition of the Atrophic Border and its Significance in Chronic Gastritis". Endoscopy 1 (3): 87–97. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1098086. ISSN 0013-726X.

- ↑ "Chinese consensus on chronic gastritis (2017, Shanghai).". Journal of Digestive Diseases 19 (4): 182–203. 2018. doi:10.1111/1751-2980.12593. PMID 29573173.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|