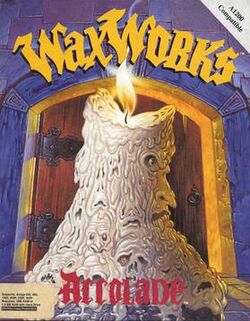

Software:Waxworks (1992 video game)

| Waxworks | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Horror Soft |

| Publisher(s) | Accolade |

| Designer(s) | Michael Woodroffe Alan Bridgman Simon Woodroffe |

| Artist(s) | Maria Drummond Paul Drummond Kevin Preston Jef Wall |

| Writer(s) | Richard Moran |

| Composer(s) | Jezz Woodroffe |

| Platform(s) | Amiga, DOS, Macintosh |

| Release | November 1992[1] |

| Genre(s) | Role-playing |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Waxworks is a horror-themed, first person dungeon crawl video game developed by Horror Soft and released in 1992. for Amiga, Macintosh, and DOS. The DOS release retains the Amiga 32-color palette rather than 256-color VGA graphics.[2] This was the last game made by Horror Soft before they became Adventure Soft, the company known for the Simon the Sorcerer series. Waxworks was inspired by the 1988 film Waxwork.[3]

In 2009, the game was re-released on GOG.com using DOSBox with compatibility for macOS and Windows.[4]

Gameplay

Waxworks is a first-person dungeon crawl role-playing video game. The game is divided into five different time periods: Ancient Egypt, Medieval Transylvania, Victorian England, an industrial mine period and Ixona's period. Three of those time periods have a mixture of puzzle-solving and combat, while the Victorian England and Ixona ones are more puzzle-solving oriented. The levels may be completed in any order, except for Ixona's period, which must be done last. Once a time period is completed, the player is reset to level one and loses all items and weapons, which do not transfer to other levels. The player levels up in each time period by defeating enemies, solving puzzles and exploring new areas, which increases maximum health and psychic power, the latter of which can be used to contact Uncle Boris. The player can use Uncle Boris' crystal ball to get hints and healing: the reagents needed for the healing spell depend on the level.

In each time period, the player moves through a series of tight corridors using a bitmap sprite-based point-and-click interface picking up items, solving puzzles, avoiding traps and engaging in combat with various opponents. During combat, players can target their opponent's individual body parts, such as the head or arms. The main objective is to collect a special item from each of the evil twin ancestors before venturing into the Ixona period to undo the family curse.

Plot

Long ago, the witch Ixona stole a chicken from the player character's ancestor, who chopped off her hand as punishment. In retaliation, Ixona placed a curse on the ancestor: whenever twins were born into his family line, one would grow up to be good while the other would become evil and serve Beelzebub.

In the present day, the protagonist learns that his twin brother, Alex, is going to suffer the curse. Boris, their uncle, has died and left them with his eponymous waxworks in his will, as well a crystal ball, through which his spirit communicates with his nephew. Boris informs his nephew that, to save Alex, he must rid the family of Ixona's curse by using the waxworks to travel through four locations in different time periods: an Ancient Egyptian pyramid, Victorian-era London, a zombie-infested cemetery, and an abandoned mine. Within each location, he is to defeat one of the four worst evil twins—the High Priest, a worshipper of Anubis; Jack the Ripper, a serial killer that sacrificed call girls to Beelzebub; Vladimir, a necromancer who raised a zombie army; and the Evil One, a cult leader who transformed himself and his followers into plant mutants.

Once all the evil twins have been defeated, Boris declares that the only way to break the curse is to prevent it from being cast in the first place, and provides his nephew with four artifacts from the evil twins: the High Priest's amulet, Jack the Ripper's knife, Vladimir's ring, and a vial of the Evil One's potion. Using the final waxwork, the protagonist travels to confront Ixona, and, following Boris' instructions, uses the artifacts to kill Ixona before she can place the curse. As a result, the curse is erased from existence for every afflicted generation of the protagonist's family line. The protagonist returns to the present and revives Alex, who tells him about a dream in which Ixona placed a curse upon her attacker before she died, transforming him into a demon. The brothers then leave the museum.

Development

Waxworks was in development over the course of two years.[8] In a 1992 interview with Zero magazine, designer Michael Woodroffe: "With the system we use, which we also invented and developed, we're able to complete a massive game such as Waxworks in about seven, eight or, at the most, nine months ... we can do everything with a small amount of people. Just three artists ... Waxworks has been put together by a team, essentially, of five." In response to being asked if any of the gore had to be censored in the game due to objection from the publisher, Woodroffe responded "Not really, no ... [the artists are] given a total brief - which they hardly ever stick to ... but they're kept within fairly strict guidelines."[3]

The game uses the AGOS engine, which is a modified version of the AberMUD 5 engine. The story for Waxworks was developed by Rick Moran. Original music was composed by Jezz Woodroffe who worked with John Canfield for the sound design. Producers Todd Thorson and Mark Wallace worked with the help of David Friedland and Tricia Woodroffe, who managed the technical resources.[9] Woodroffe also stated that the game was heavily inspired by the 1988 film Waxwork. Furthermore, a fight with the Marquis de Sade, who was a major character in the film, was cut from the game.[3] Similarities between the game and the movie include time travel using waxwork displays and the artifacts belonging to those within the displays having magical properties.

Woodroffe stated that there will be "numerous kings and queens ... There'll also be triffids" and that there will be a devil worship scene with "chanting and leaping about."[3] Some of the plant mutant traps in the finished game bear a close resemblance to Triffids. Kings and queens are absent from the game entirely, however in the Egypt level the player takes the role of a prince saving a princess from being sacrificed by a cult, but there is no chanting or outright worship depicted and the cult does not worship the devil: it is a cult of Anubis.[10][11]

In a pre-release blurb for Waxworks in Amiga Action, the introduction, particularly surrounding Uncle Boris, is different than what is in the final game. The introduction outlined in Amiga Action begins in a graveyard, rather than at Uncle Boris' waxworks, and Uncle Boris is stated to contact the protagonist telepathically, rather than with a crystal ball as in the final game. Upon visiting Boris' tomb, it is "blown open and the coffin disappears. Looking into the tomb, [the protagonist] sees images of himself and his brother Alex lying dead at the bottom."[8] The backstory represented in the manual and The Curse of the Twins booklet included with the game also has nothing related to this pre-release introduction, possibly indicating it was scrapped and the story was reworked before release.[12][13][14]

Copy protection

At the beginning of the game, the player is prompted to enter a 4-digit code which requires the use of a 3-ply code wheel to determine the answer. The wheel has a symbol, a monster and a place on the three rings, the third ring having two different words and two different codes on several of the answers.[15] If the player fails to enter the correct answer three times, the game closes itself and suggests that the player refer to the manual.[12]

Reception

| Reception | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

Many reviewers noted the game's gore, with Amiga Joker calling it "pretty horrible, horribly pretty" and "shocking", and PC Games saying "Waxworks is definitely only for enthusiastic horrorfreaks."[5][6] The One refers to Waxworks' gore as "very gruesome ... a lot of this stuff is genuinely stomach-turning". In addition, the store page for the GOG release refers to it as "A dungeon crawler known for its gore and death scenes."[4]

Computer Gaming World criticized the small game maps, overemphasis on combat, and the IBM PC version's use of an Amiga-like 32-color palette instead of 256-color VGA graphics, but liked the "very atmospheric" soundtrack. The magazine concluded that despite flaws, the game was "better than most" CRPGs, and that "for those who revel in the macabre" ... Waxworks continues to satisfy the bent toward the supernatural".[2] Computer Gaming World nominated Waxworks for game of the year under the role-playing category.

The One gave the Amiga version of Waxworks an overall score of 78%, stating they "like the game's episodic nature - the way it's broken down into separate mini-adventures is far more suited to my tastes ... it adds variety to the fun, and as a result the game's much fresher than most run-of-the-mill RPGs", and complimented the game's atmosphere and express that "The moody graphics and soundtrack combine to create a strong sense of tension". The One criticized the game's gratuitous gore.[7]

References

- ↑ "Just Around the Corner". Amiga Force (Europress) (1): 20. October 1992. https://archive.org/details/amiga-force-01/page/n19.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Miller, Chuck (February 1993). "Accolade's Waxworks". Computer Gaming World: 50. http://www.cgwmuseum.org/galleries/index.php?year=1993&pub=2&id=103. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Michael Woodroffe Interview". Zero Magazine (Dennis Publishing Ltd.): 55–56. February 1992. https://archive.org/details/zero-magazine-28/page/n53.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "GOG Waxworks Release". https://www.gog.com/game/waxworks.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Waxworks Amiga Review". Amiga Joker (Joker Verlag): 12. December 1992. https://archive.org/details/Amiga_Joker_1992-12_Joker_Verlag_DE/page/n11.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "Waxworks Review". PC Games (Computec Media AG): 58. January 1993. https://archive.org/details/pcgamesmagazine-1993-01/page/n57.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "Waxworks Review". The One (emap Images) (52): 64–65. January 1993. https://archive.org/details/theone-magazine-52/page/n63.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "A Wax In The Works". Amiga Action (Europress) (36): 12. September 1992. https://archive.org/details/Amiga_Action_Issue_36_1992-09_Europress_Interactive_GB/page/n11.

- ↑ Waxworks (1992). Horror Soft. Accolade. Scene: Credits.

- ↑ Waxworks (1992). Horror Soft. Accolade. Scene: Egypt.

- ↑ Waxworks (1992). Horror Soft. Accolade. Scene: Plant Mutant Mine.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Waxworks (1992). Horror Soft. Accolade. Scene: Introduction.

- ↑ Waxworks Manual. https://archive.org/details/vgmuseum_miscgame_waxworks-manual/.(1992). Horror Soft. Accolade.

- ↑ The Curse of the Twins. https://archive.org/details/vgmuseum_miscgame_waxworks-story.(1992). Horror Soft. Accolade.

- ↑ "Waxworks PC Code Wheel". https://mocagh.org/loadpage.php?getgame=waxworks.

- ↑ Lesser, Hartley; Lesser, Patricia; Lesser, Kirk (April 1993). "The Role of Computers". Dragon (192): 60–62. https://archive.org/stream/DragonMagazine260_201801/DragonMagazine192#page/n61/mode/2up.

- ↑ "Waxworks Review". Datormagazin (Egmont Publishing): 58. January 1993. https://archive.org/details/Datormagazin1993_201809/page/n57.

- ↑ "Waxworks Review". Power Play Magazine (Markt&Technik): 49. January 1993. https://archive.org/details/powerplaymagazine-1993-01/page/n47.

- ↑ "Taking a peek - Nominee Awards". Computer Gaming World (Software Publishers Association) (108): 155. July 1993. https://archive.org/details/Computer_Gaming_World_Issue_108/page/n153.

External links

- Waxworks at MobyGames

- Waxworks at the Hall of Light

- Waxworks DOS Version, playable in-browser at Archive.org

|