Biology:Plestiodon laticeps

| Broad-headed skink | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification Error creating thumbnail: Unable to save thumbnail to destination

| |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Family: | Scincidae |

| Genus: | Plestiodon |

| Species: | P. laticeps

|

| Binomial name | |

| Plestiodon laticeps (Schneider, 1801)

| |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The broad-headed skink or broadhead skink (Plestiodon laticeps) is species of lizard, endemic to the southeastern United States.[1] The broadhead skink occurs in sympatry with the five-lined skink (Plestiodon fasciatus) and Southeastern five-lined skink (Plestiodon inexpectatus) in forest of the Southeastern United States. All three species are phenotypically similar throughout much of their development and were considered a single species prior to the mid-1930s.[3]

Description

Together with the Great Plains skink it is the largest of the "Plestiodon skinks", growing from a total length of 15 cm (5.9 in) to nearly 33 cm (13 in).

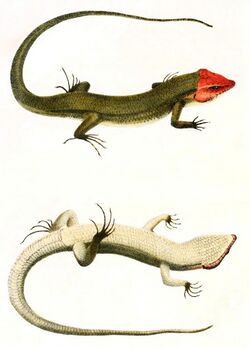

The broad-headed skink gets its name from the wide jaws, giving the head a triangular appearance. Adult males are brown or olive brown in color and have bright orange heads during the mating season in spring. Females have five light stripes running down the back and the tail, similar to the Five-lined Skink. However, they can be distinguished by having five labial scales around the mouth, whereas Five-lined skinks have only four.[4] Juveniles are dark brown or black and also striped and have blue tails.

Habitat

Broad-headed skinks are semi-arboreal lizards that are strongly associated with live oak trees. It does not appear that the lizards have a preference for tree size, rather they prefer trees with holes. Juveniles stay closer to the ground on low or fallen branches.[5] Males have been known to guard preferred trees that are surrounded with dense brushes to limit attack by predators and harbor prey.[6] Dead and decaying trees are important habitat resources for nesting.[7] The occurrence of the species was seen to correlate with the presence of Black Walnut (Juglans nigra). [8]

Behavior

Broad-headed skinks are the most arboreal of the North American Plestiodon. They forage on the ground, but also easily and often climb trees for shelter, to sleep, or to search for food. Broad-headed skinks often feed on what are called "hidden prey"; prey items that can only be located by searching under debris, soil or litter.[9] Broad-headed skinks are preyed on by a variety of organisms including carnivorous birds, larger reptiles, and mammals. Skinks prefer to flee by climbing a nearby tree or seeking shelter under foliage.[5] These skinks exhibit tail autotomy when caught by a predator. The tails break away and continue to move, distracting the predator and allowing the skink to flee.[5] Typically, females will flee before males do when found in pairs.[10] Broad-headed Skinks rely on coloration and directional stimuli to determine which end of their prey item to attack.[11] When consuming large invertebrates, they often carry them to shelter to avoid being preyed upon during the prey handling time.[12]

Reproduction

Males typically are larger than females.[13] The larger the female, the more eggs she will lay. Males thus often try to mate with the largest female they can find, and they sometimes engage in severe fights with other males over access to a female. Large adult males in South Carolina will guard females within their territories and chase away smaller males. [14] Females will also mate with the largest males they can find, a result of the Good Genes Hypothesis.[15] Females only have a preference on body size of males when reproducing, they tend to look over the more dominant feature of bright orange heads on this species.[16] Females emit a pheromone from glands in the base of the tail when they are sexually receptive and males can find them by tracking their chemical trails through tongue-flicking.[17] Males show higher tongue flicking rates when exposed to conspecific females verses heterospecific females when mating and will terminate behavioral interaction without initiating courtship if the pheromones do not match the species.[18] The female lays between 8 and 22 eggs, which she guards and protects until they hatch in June or July. Female broadhead skinks will lay their clutch in decaying log cavities, and they have been observed to create a sort of nest by packing down debris within their cavities.[19] The hatchlings have a total length of 6 centimetres (2.4 in) to 8 centimetres (3.1 in).

Geographic range

Broad-headed skinks are widely distributed in the southeastern states of the United States , from the East Coast to Kansas and eastern Texas and from Ohio to the Gulf Coast.

Nonvenomous

These skinks (along with the similar Plestiodon fasciatus) are sometimes wrongly thought to be venomous.[20] Broad-headed skinks are nonvenomous.

See also

- Gilbert's Skink - similar morphology

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hammerson, G.A. (2007). "Plestiodon laticeps". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2007: e.T64231A12756745. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2007.RLTS.T64231A12756745.en.

- ↑ The Reptile Database. www.reptile-database.org.

- ↑ Watson, Charles, M.; Formanowicz, Daniel, R. (2012). "A COMPARISON OF MAXIMUM SPRINT SPEED AMONG THE FIVE-LINED SKINK (PLESTIODON) OF THE SOUTHEASTERN UNITED STATES AT ECOLOGICALLY RELEVANT TEMPERATURES". Herpetological Conservation and Biology 7 (1): 75–82. http://herpconbio.org/Volume_7/Issue_1/Watson_Formanowicz_2012.pdf.

- ↑ Division., Connecticut. Department of Environmental Protection. Connecticut. Wildlife (1997). Five-lined skink.. Connecticut Dept. of Environmental Protection, Wildlife Division. OCLC 43556290. http://worldcat.org/oclc/43556290.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Vitt, Laurie; Cooper, William (1986). "Foraging and Diet of a Diurnal Predator (Eumeces Laticeps) Feeding on Hidden Prey.". Journal of Herpetology 20 (3): 408–415. doi:10.2307/1564503. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1564503.

- ↑ Cooper, William, E. (1993). "Tree Selection by the broad-headed skink, Eumeces laticeps: size, holes, and cover". Amphibia-Reptilia 14 (3): 285–294. doi:10.1163/156853893X00480. https://doi.org/10.1163/156853893X00480.

- ↑ Hullinger, Allison; Cordes, Zackary; Riedle, Daren; Stark, William (2020). "Habitat assessment of the Broad-headed Skink (Plestiodon laticeps) and the associated squamate community in eastern Kansas". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science 123 (1–2): 137. doi:10.1660/062.123.0111. https://bioone.org/journals/transactions-of-the-kansas-academy-of-science/volume-123/issue-1-2/062.123.0111/----Custom-HTML----Habitat/10.1660/062.123.0111.short.

- ↑ Hullinger, Allison; Cordes, Zackary; Riedle, Daren; Stark, William (2020). "Habitat Assessment of the Broad-Headed Skink (Plestiodon laticeps) and the Associated Squamate Community in Eastern Kansas" (in English). Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science 123 (1–2): 137. doi:10.1660/062.123.0111. ISSN 0022-8443. https://doi.org/10.1660/062.123.0111.

- ↑ Vitt, Laurie; Cooper, William (1986). "Tail loss, tail color, and predator escape in Eucemes (Lacertilia: Scincidae) age-specific differences in costs and benefits". Canadian Journal of Zoology 64 (3): 583–592. doi:10.1139/z86-086. https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/abs/10.1139/z86-086.

- ↑ Cooper, W. E., & Vitt, L. J. (2002). Increased predation risk while mate guarding as a cost of reproduction for male broad-headed skinks (Eumeces laticeps). Acta Ethologica, 5(1), 19. 10.1007/s10211-002-0058-1

- ↑ Cooper, W. E. (1981). Visual guidance of predatory attack by a scincid lizard, Eumeces laticeps. Animal Behaviour, 29(4), 1127-1136. 10.1016/S0003-3472(81)80065-6

- ↑ Cooper, William (2000). "Tradeoffs Between Predation Risk and Feeding in a Lizard, the Broad-Headed Skink (Eumeces Laticeps)". Behaviour 137 (9): 1175–1189. doi:10.1163/156853900502583. ISSN 0005-7959. http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/156853900502583.

- ↑ "Species Profile: Broadhead Skink." Savannah River Ecology Laboratory, University of Georgia. https://srelherp.uga.edu/lizards/eumlat.htm

- ↑ Laurie J. Vitt and William E. Cooper Jr.. 2011. The evolution of sexual dimorphism in the skink Eumeces laticeps: an example of sexual selection. Canadian Journal of Zoology. 63(5): 995-1002. https://doi.org/10.1139/z85-148

- ↑ Cooper, William; Vitt, Laurie (1993). Female mate choice of large male broad-headed skinks (4 ed.). Animal Behavior. ISBN 5-02-022461-8. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0003347283710833.

- ↑ Cooper, William E.; Vitt, Laurie J. (April 1993). "Female mate choice of large male broad-headed skinks". Animal Behaviour 45 (4): 683–693. doi:10.1006/anbe.1993.1083. ISSN 0003-3472. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/anbe.1993.1083.

- ↑ "Virginia Herpetological Society" (in en). http://www.virginiaherpetologicalsociety.com/.

- ↑ Cooper, W. E., Garstka, W. R., & Vitt, L. J. (1986). Female Sex Pheromone in the Lizard Eumeces laticeps. Herpetologica, 42(3), 361–366. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3892314

- ↑ Vitt, Laurie J.; Cooper, William E. (1985). "The Relationship between Reproduction and Lipid Cycling in the Skink Eumeces laticeps with Comments on Brooding Ecology". Herpetologica 41 (4): 419–432. ISSN 0018-0831. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3892111.

- ↑ Conant, R., & J.T. Collins. 1998. A Field Guide to Reptiles & Amphibians: Eastern and Central North America, Third Edition. Peterson Field Guides. Houghton Mifflin. Boston and New York. 640 pp. ISBN:0-395-90452-8. (Eumeces laticeps, p. 263.)

Further reading

- Behler, J.L., and F.W. King. 1979. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Knopf. New York. 743 pp. (Eumeces laticeps, pp. 573–574 + Plates 424, 431.)

- Conant, R. 1975. A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern North America, Second Edition. Houghton Mifflin. Boston. xviii + 429 pp. ISBN:0-395-19979-4 (hardcover), ISBN:0-395-19977-8 (paperback). (Eumeces laticeps, pp. 123–124, Figures 26-27 + Plate 19 + Map 76.)

- Schneider, J.G. 1801. Historiae Amphibiorum naturalis et literariae continens...Scincos... Frommann. Jena. vi + 364 pp. + Plates I.- II. (Scincus laticeps, pp. 189–190.)

- Smith, H.M., and E.D. Brodie, Jr. 1982. Reptiles of North America: A Guide to Field Identification. Golden Press. New York. 240 pp. ISBN:0-307-13666-3. (Eumeces laticeps, pp. 76–77.)

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q2697347 entry

|