Biology:Three-toed jacamar

| Three-toed jacamar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Piciformes |

| Family: | Galbulidae |

| Genus: | Jacamaralcyon Lesson, 1830 |

| Species: | J. tridactyla

|

| Binomial name | |

| Jacamaralcyon tridactyla (Vieillot, 1817)

| |

| |

| Synonyms | |

The three-toed jacamar (Jacamaralcyon tridactyla) is a species of bird in the family Galbulidae. It is monotypic within the genus Jacamaralcyon.

It is endemic to Brazil. Its natural habitats are subtropical or tropical dry forest, subtropical or tropical moist lowland forest, and plantations. It is threatened by habitat loss.

Taxonomy and etymology

The three-toed jacamar is one of 18 jacamar species in the family Galbulidae. It is in the monotypic genus Jacamaralcyon,[3] and has no subspecies.[4] When he first described it in 1807, French naturalist François Levaillant named the species "jacamaralcion", a combination of the words "jacamar" and "alcyon" — the latter a form of the word "halcyon", meaning "kingfisher".[5] French ornithologist Louis Pierre Vieillot assigned it to the large jacamar genus Galbula when he established a scientific name for it in 1817, naming it Galbula tridactyla. In 1830, French ornithologist René Primevère Lesson created the genus Jacamaralcyon, separating the three-toed jacamar from other jacamar species on the basis of its unusual foot structure;[6] the genus name is a nod to Levaillant's earlier common name for the bird.[5] The specific name tridactyla is a combination of the Greek words tri, meaning "three" and dactulos, meaning "toes".[5]

Description

Like all members of its family, the three-toed jacamar is short-legged and short-winged. It perches upright, with its tail down and its long, sharply-pointed beak uptilted.[7] It is a medium-sized bird, measuring 18 cm (7.1 in) in length[8] and weighing between 17.4 and 19.3 g (0.61 and 0.68 oz); females average heavier than males.[9] The sexes are similarly plumaged: slaty black with a bronzy-green gloss above, and somewhat paler below. The belly and the center of the breast are white. The adult has a brownish-gray cap and a black throat, and the cap, chin and the sides of the head are finely marked with pale fulvous streaks. Its bill is black, and its feet are slaty gray.[2]

Unlike other members of its family, the three-toed jacamar has three, rather than four, toes. Its small zygodactyl feet are missing a hind toe, and the front two toes are fused together at the base.[7]

Habitat and range

Endemic to southeastern Brazil, the three-toed jacamar is found in drier parts of the Atlantic Forest.[7] It is now restricted to the states of Rio de Janeiro (primarily in the Paraíba do Sul valley) and eastern Minas Gerais, though populations also formerly existed in the states of Espírito Santo, São Paulo and Paraná. Although it is generally found in intact forest, it can survive in more degraded areas, such as plantations, provided that a native understory layer persists. There is some evidence that it is associated with streams, as it needs earthen banks in which to nest; it also uses banks created by road cuttings.[8] The species is largely sedentary, though youngsters disperse after fledging, and adults sometimes move short distances.[7]

Behavior

Although it is a colonial nester, the three-toed jacamar is generally found singly or in pairs. It sometimes joins mixed species flocks.[7]

Food and feeding

Like all jacamars, the three-toed jacamar is an insectivore.[7] It feeds preferentially on small, cryptically colored moths and butterflies, and Hymenoptera, but will also take flies, dragonflies, beetles, true bugs and termites.[8] It hunts from an open perch in the forest understory or along the forest edge, sallying after prey which it often beats on a branch; this serves to stun the insect, and to remove any stinger or venom,[7] as well as the wings.[10]

Breeding

Three-toed jacamars breed during Brazil's rainy season, with vocalizations and other courtship behaviors increasing between September and February.[10] During courtship, rival males sit side by side on a branch, flicking their wings and pumping their tails as they sing. Territories are defended vocally, with rivals rarely resorting to physical confrontation.[7] The species excavates a burrow nest, using one foot at a time to dig into an earthen bank; evidence (in the form of dirty and broken beaks on female museum specimens) suggests that the female may do most or all of the nest digging. Burrows are 6 cm (2.4 in) wide and 6–9 cm (2.4–3.5 in) high, and may extend as much as 72 cm (28 in) into the bank.[10] The species tends to nest colonially.[7] The female lays 2–4 eggs.[7]

Voice

The three-toed jacamar's song is a shrill series of short, ascending whistles, lasting about 20 seconds. Unlike most jacamars, which typically sing alone, male three-toed jacamars tend to sing in groups of 2–6.[10]

Conservation and threats

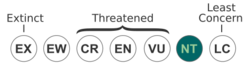

The three-toed jacamar is a species in trouble; habitat loss and habitat degradation have contributed significantly to its steep decline, and it is now rated as Near Threatened by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. Its total population is estimated at 350–1500 individuals, which survive in small, widely scattered pockets of appropriate habitat across southeastern Brazil.[8]

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2020). "Jacamaralcyon tridactyla". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T22682186A153924733. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22682186A153924733.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22682186/153924733. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Sharpe, Richard Bowdler, ed (1891). Catalog of the Birds in the British Museum. 19. London, UK: The British Museum. pp. 174–5. https://books.google.com/books?id=2RK4ot2EKtEC&pg=PA174.

- ↑ "ITIS Report: Jacamaralcyon". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=553564. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ↑ "ITIS Report: Jacamaralcyon tridactyla". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=554324. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Names. London, UK: Christopher Helm. pp. 210, 390. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4. https://archive.org/details/Helm_Dictionary_of_Scientific_Bird_Names_by_James_A._Jobling.

- ↑ Chenu, Jean Charles; des Murs, O. (1860) (in French). Encyclopédie d'histoire naturelle ou Traité complet de cette science, d'après les travaux des naturalistes les plus éminents de tous les pays et de toutes les époques: Oiseaux. Paris, France: Marescq. p. 38. https://books.google.com/books?id=E9g9JsJmRMYC&pg=RA1-PA16.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 Harris, Tim, ed (2009). National Geographic Complete Birds of the World. Washington, DC, US: National Geographic Society. pp. 185–6. ISBN 978-1-4262-0403-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=0TIiIdLp9xkC&pg=PA185.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 "BirdLife Species Factsheet: Three-toed Jacamar (Jacamaralcyon tridactyla)". BirdLife International. http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/search/species_search.html?action=SpcHTMDetails.asp&sid=883&m=0. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ↑ Dunning Jr., John B. (2008). CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL, US: CRC Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-4200-6445-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=TcnOTPILlcEC&pg=PA209.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Silveira, Luís Fábio; Nobre, Henrique Rocha (Spring 1998). "New records of Three-toed Jacamar, Jacamaralcyon tridactyla, in Minas Gerais, Brazil, with some notes on its biology". Cotinga 9: 47–51. ISSN 1353-985X. https://www.neotropicalbirdclub.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Cotinga-09-1998-47-51.pdf. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

External links

- Three-toed jacamar photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- "Three-toed jacamar media". Internet Bird Collection. http://www.hbw.com/ibc/species/three-toed-jacamar-jacamaralcyon-tridactyla.

Wikidata ☰ Q1272616 entry

|