Biology:Rugosodon

| Rugosodon | |

|---|---|

| |

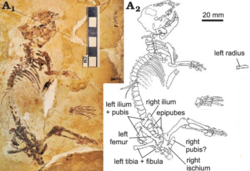

| Fossil and interpretive drawing | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | †Multituberculata |

| Genus: | †Rugosodon Yuan et al., 2013 |

| Species: | †R. eurasiaticus

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Rugosodon eurasiaticus Yuan et al., 2013

| |

Rugosodon is an extinct genus of multituberculate (rodent-like) mammals from eastern China that lived 160 million years ago during the Jurassic period. The discovery of its type species and currently only known species Rugosodon eurasiaticus was reported in the 16 August 2013 issue of Science.

Description

Rugosodon is represented by a nearly complete fossilized skeleton, including a skull, that bears a strong resemblance to a small rat or a chipmunk. The mammal is estimated to have weighed 65–80 g (2.3–2.8 oz), about that of an average chipmunk. The generic name Rugosodon (Latin for "wrinkly tooth") refers to the rugosity, or wrinkliness, of the distinctively shaped teeth.[1][2] Its teeth indicate that the animal was an omnivore, well-adapted to gnawing both plants and animals, including fruits and seeds, worms, insects and small vertebrates. Its ankle joints were highly mobile at rotation.[3] This means that the ankle is remarkably flexible, allowing the foot to hyper-extend downward—like a ballerina standing on pointed toes—and to rotate through a wide range of motion. This feature, along with highly mobile digits, defines the multituberculates and is not seen in other mammalian lineages of the era. Rugosodon also had a highly flexible spine, which would have allowed it to twist both left to right and front to back.[2] Due to the proportions of its hand bones, it is thought to have been terrestrial rather than arboreal. Its diet was likely omnivorous.[4]

Discovery and taxonomic significance

In 2009, a local fossil hunter unearthed an unusual fossil in the Tiaojishan Formation of China's Liaoning province, dating to 160 million years ago. He turned the fossil over to the Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, where it was eventually identified as a nearly complete skeleton and given the name Rugosodon eurasiaticus.[5] The fossil was discovered on what was the shore of an ancient lake.[6] It was preserved in two shale slabs and measures about 17 cm (6.5 inches) long from head to rump. The site of the discovery consists of lake sediments with embedded volcanic layers, which also contained fossils of feathered dinosaur Anchiornis and the pterosaur Darwinopterus.[4][3] The dental features of Rugosodon most resemble those of multituberculates of the Late Jurassic of Western Europe, suggesting that Europe and Asia had extensive mammal faunal interchanges (hence the specific name, eurasia) during the Jurassic.[4][3][7]

Prior to the discovery of Rugosodon, scientists knew that multituberculates living 66 million years ago had highly flexible ankles.[6] However, older species were mostly known from small fragments, and it was not proven that the trait was ancestral. Additionally, it was unknown what sort of diet was primitive in the lineage.[5] The presence of the characteristic flexible ankles in Rugosodon demonstrates that the trait is ancestral and provides a strong clue that the trait was a major factor in the lineage's evolutionary success.[6] The animal's diet provides a bridge between very early mammals, which were mostly insectivores, and later multituberculates, which were mostly herbivores.[5]

In the initial description, Rugosodon was attributed to Paulchoffatiidae, a group of multituberculates otherwise known from Western Europe. However, later studies suggested that it lacked key morphological features of the family, and was instead placed as a member of the more inclusive Paulchoffatiid-line outside of any defined family,[8] or possibly even more basally than that.[9]

References

- ↑ Michael Balter (15 August 2013). "ScienceShot: Meet 'Wrinkly Tooth,' the Earliest Rodentlike Creature". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. http://news.sciencemag.org/paleontology/2013/08/scienceshot-meet-%E2%80%98wrinkly-tooth%E2%80%99-earliest-rodentlike-creature.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Perkins, Sid (15 August 2013). "Fossil reveals features of mammal line that outlived dinosaurs". Nature. http://www.nature.com/news/fossil-reveals-features-of-mammal-line-that-outlived-dinosaurs-1.13568.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 AAAS (15 August 2013). "Unearthed: Fossil of history's most successful mammal". EurekAlert. American Association for the Advancement of Science. http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2013-08/aaft-ufo080913.php.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Earliest evolution of multituberculate mammals revealed by a new Jurassic fossil". Science 341 (6147): 779–783. 2013. doi:10.1126/science.1237970. PMID 23950536. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/255959258_Earliest_Evolution_of_Multituberculate_Mammals_Revealed_by_a_New_Jurassic_Fossil.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Veronique Greenwood (16 August 2013). "An Ancient Mammal Paves the Way for Modern Rodents". TIME. http://science.time.com/2013/08/16/an-ancient-mammal-paves-the-way-for-modern-rodents/.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Ker Than (15 August 2013). "Fossil Reveals Long-Lived Mammal Group's Secret". National Geographic. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/08/130815-multituberculate-rugosodon-early-mammal-evolution/.

- ↑ "ScienceShot: Meet ‘Wrinkly Tooth,’ the Earliest Rodentlike Creature". ScienceMag. https://www.science.org/content/article/scienceshot-meet-wrinkly-tooth-earliest-rodentlike-creature.

- ↑ Martin, Thomas; O. Averianov, Alexander; A. Schultz, Julia; H. Schwermann, Achim; Wings, Oliver (2019-08-07). "Late Jurassic multituberculate mammals from Langenberg Quarry (Lower Saxony, Germany) and palaeobiogeography of European Jurassic multituberculates". Historical Biology 33 (5): 616–629. doi:10.1080/08912963.2019.1650274. ISSN 0891-2963. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2019.1650274.

- ↑ King, Benedict; Beck, Robin MD (2020-06-10). "Tip dating supports novel resolutions of controversial relationships among early mammals". Proceedings of the Royal Society B 287 (1928): 20200943. doi:10.1098/rspb.2020.0943. ISSN 1471-2954. PMC 7341916. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rspb.2020.0943.

External links

- Supplemental Material to Yuan et al. 2013 (169 p.)

- Paleobiology Database

- News with photograph at World Fossil Society

Wikidata ☰ Q14752840 entry

|