Biology:STED microscopy

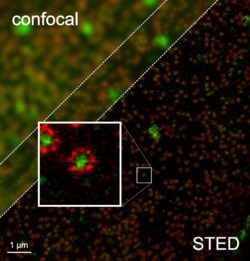

Stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy is one of the techniques that make up super-resolution microscopy. It creates super-resolution images by the selective deactivation of fluorophores, minimizing the area of illumination at the focal point, and thus enhancing the achievable resolution for a given system.[1] It was developed by Stefan W. Hell and Jan Wichmann in 1994,[2] and was first experimentally demonstrated by Hell and Thomas Klar in 1999.[3] Hell was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2014 for its development. In 1986, V.A. Okhonin[4] (Institute of Biophysics, USSR Academy of Sciences, Siberian Branch, Krasnoyarsk) had patented the STED idea.[5] This patent was unknown to Hell and Wichmann in 1994.

STED microscopy is one of several types of super resolution microscopy techniques that have recently been developed to bypass the diffraction limit of light microscopy to increase resolution. STED is a deterministic functional technique that exploits the non-linear response of fluorophores commonly used to label biological samples in order to achieve an improvement in resolution, that is to say STED allows for images to be taken at resolutions below the diffraction limit. This differs from the stochastic functional techniques such as photoactivated localization microscopy (PALM) and stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) as these methods use mathematical models to reconstruct a sub diffraction limit from many sets of diffraction limited images.

Background

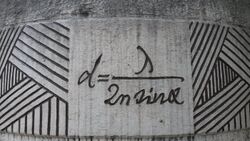

In traditional microscopy, the resolution that can be obtained is limited by the diffraction of light. Ernst Abbe developed an equation to describe this limit. The equation is:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{D} = \frac{\lambda}{2n\sin{\alpha}} = \frac{\lambda}{\mathrm{2NA}} }[/math]

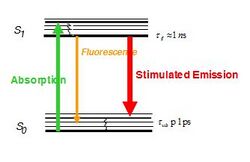

where D is the diffraction limit, λ is the wavelength of the light, and NA is the numerical aperture, or the refractive index of the medium multiplied by the sine of the angle of incidence. n describes the refractive index of the specimen, α measures the solid half‐angle from which light is gathered by an objective, λ is the wavelength of light used to excite the specimen, and NA is the numerical aperture. To obtain high resolution (i.e. small d values), short wavelengths and high NA values (NA = n sinα) are optimal.[6] This diffraction limit is the standard by which all super resolution methods are measured. Because STED selectively deactivates the fluorescence, it can achieve resolution better than traditional confocal microscopy. Normal fluorescence occurs by exciting an electron from the ground state into an excited electronic state of a different fundamental energy level (S0 goes to S1) which, after relaxing back to the ground state (of S1), emits a photon by dropping from S1 to a vibrational energy level on S0. STED interrupts this process before the photon is released. The excited electron is forced to relax into a higher vibration state than the fluorescence transition would enter, causing the photon to be released to be red-shifted as shown in the image to the right.[7] Because the electron is going to a higher vibrational state, the energy difference of the two states is lower than the normal fluorescence difference. This lowering of energy raises the wavelength, and causes the photon to be shifted farther into the red end of the spectrum. This shift differentiates the two types of photons, and allows the stimulated photon to be ignored.

To force this alternative emission to occur, an incident photon must strike the fluorophore. This need to be struck by an incident photon has two implications for STED. First, the number of incident photons directly impacts the efficiency of this emission, and, secondly, with sufficiently large numbers of photons fluorescence can be completely suppressed.[8] To achieve the large number of incident photons needed to suppress fluorescence, the laser used to generate the photons must be of a high intensity. Unfortunately, this high intensity laser can lead to the issue of photobleaching the fluorophore. Photobleaching is the name for the destruction of fluorophores by high intensity light.

Process

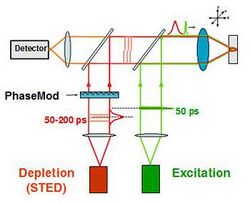

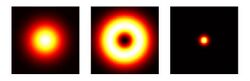

STED functions by depleting fluorescence in specific regions of the sample while leaving a center focal spot active to emit fluorescence. This focal area can be engineered by altering the properties of the pupil plane of the objective lens.[9][10][11] The most common early example of these diffractive optical elements, or DOEs, is a torus shape used in two-dimensional lateral confinement shown below. The red zone is depleted, while the green spot is left active. This DOE is generated by a circular polarization of the depletion laser, combined with an optical vortex. The lateral resolution of this DOE is typically between 30 and 80 nm. However, values down to 2.4 nm have been reported.[12] Using different DOEs, axial resolution on the order of 100 nm has been demonstrated.[13] A modified Abbe's equation describes this sub diffraction resolution as:

[math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{D} = \frac{\lambda}{2 n \sin{\alpha} \sqrt{1 + \frac{I}{I_\text{sat}}}} = \frac{\lambda}{\mathrm{2NA} \sqrt{1 + \sigma}} }[/math]

Where [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] is the refractive index of the medium, [math]\displaystyle{ I }[/math] is the intracavity intensity and [math]\displaystyle{ I_\text{sat} }[/math] is the saturation intensity. Where [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math] is the saturation factor expressing the ratio of the applied (maximum) STED intensity to the saturation intensity, [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma = I_\text{max}/I_\text{sat} }[/math].[6][14]

To optimize the effectiveness of STED, the destructive interference in the center of the focal spot needs to be as close to perfect as possible. That imposes certain constraints on the optics that can be used.

Dyes

Early on in the development of STED, the number of dyes that could be used in the process was very limited. Rhodamine B was named in the first theoretical description of STED.[2] As a result, the first dyes used were laser emitting in the red spectrum. To allow for STED analysis of biological systems, the dyes and laser sources must be tailored to the system. This desire for better analysis of these systems has led to living cell STED and multicolor STED, but it has also demanded more and more advanced dyes and excitation systems to accommodate the increased functionality.[7]

One such advancement was the development of immunolabeled cells. These cells are STED fluorescent dyes bound to antibodies through amide bonds. The first use of this technique coupled MR-121SE, a red dye, with a secondary anti-mouse antibody.[8] Since that first application, this technique has been applied to a much wider range of dyes including green emitting, Atto 532,[15][16][17] and yellow emitting, Atto 590,[18] as well as additional red emitting dyes. In addition, Atto 647N was first used with this method to produce two-color STED.[19]

Applications

Over the last several years, STED has developed from a complex and highly specific technique to a general fluorescence method. As a result, a number of methods have been developed to expand the utility of STED and to allow more information to be provided.

Structural analysis

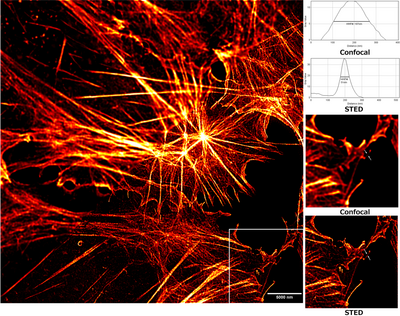

From the beginning of the process, STED has allowed fluorescence microscopy to perform tasks that had been only possible using electron microscopy. As an example, STED was used for the elucidation of protein structure analysis at a sub-organelle level. The common proof of this level of study is the observation of cytoskeletal filaments. In addition, neurofilaments, actin, and tubulin are often used to compare the resolving power of STED and confocal microscopes.[20][21][22]

Using STED, a lateral resolution of 70 – 90 nm has been achieved while examining SNAP25, a human protein that regulates membrane fusion. This observation has shown that SNAP25 forms clusters independently of the SNARE motif's functionality, and binds to clustered syntaxin.[23][24] Studies of complex organelles, like mitochondria, also benefit from STED microscopy for structural analysis. Using custom-made STED microscopes with a lateral resolution of fewer than 50 nm, mitochondrial proteins Tom20, VDAC1, and COX2 were found to distribute as nanoscale clusters.[25][26] Another study used a homemade STED microscopy and DNA binding fluorescent dye, measured lengths of DNA fragments much more precisely than conventional measurement with confocal microscopy.[27]

Correlative methods

Due to its function, STED microscopy can often be used with other high-resolution methods. The resolution of both electron and atomic force microscopy is even better than STED resolution, but by combining atomic force with STED, Shima et al. were able to visualize the actin cytoskeleton of human ovarian cancer cells while observing changes in cell stiffness.[28]

Multicolor

Multicolor STED was developed in response to a growing problem in using STED to study the dependency between structure and function in proteins. To study this type of complex system, at least two separate fluorophores must be used. Using two fluorescent dyes and beam pairs, colocalized imaging of synaptic and mitochondrial protein clusters is possible with a resolution down to 5 nm [18]. Multicolor STED has also been used to show that different populations of synaptic vesicle proteins do not mix of escape synaptic boutons.[29][30] By using two color STED with multi-lifetime imaging, three channel STED is possible.

Live-cell

Early on, STED was thought to be a useful technique for working with living cells.[13] Unfortunately, the only way for cells to be studied was to label the plasma membrane with organic dyes.[29] Combining STED with fluorescence correlation spectroscopy showed that cholesterol-mediated molecular complexes trap sphingolipids, but only transiently.[31] However, only fluorescent proteins provide the ability to visualize any organelle or protein in a living cell. This method was shown to work at 50 nm lateral resolution within Citrine-tubulin expressing mammalian cells.[32][33] In addition to detecting structures in mammalian cells, STED has allowed for the visualization of clustering YFP tagged PIN proteins in the plasma membrane of plant cells.[34]

Recently, multicolor live-cell STED was performed using a pulsed far-red laser and CLIPf-tag and SNAPf-tag expression.[35]

In the brain of intact animals

Superficial layers of mouse cortex can be repetitively imaged through a cranial window.[36] This allows following the fate and shape of individual dendritic spines for many weeks.[37] With two-color STED, it is even possible to resolve the nanostructure of the postsynaptic density in life animals.[38]

STED at video rates and beyond

Super-resolution requires small pixels, which means more spaces to acquire from in a given sample, which leads to a longer acquisition time. However, the focal spot size is dependent on the intensity of the laser being used for depletion. As a result, this spot size can be tuned, changing the size and imaging speed. A compromise can then be reached between these two factors for each specific imaging task. Rates of 80 frames per second have been recorded, with focal spots around 60 nm.[1][39] Up to 200 frames per second can be reached for small fields of view.[40]

Problems

Photobleaching can occur either from excitation into an even higher excited state, or from excitation in the triplet state. To prevent the excitation of an excited electron into another, higher excited state, the energy of the photon needed to trigger the alternative emission should not overlap the energy of the excitation from one excited state to another.[41] This will ensure that each laser photon that contacts the fluorophores will cause stimulated emission, and not cause the electron to be excited to another, higher energy state. Triplet states are much longer lived than singlet states, and to prevent triplet states from exciting, the time between laser pulses needs to be long enough to allow the electron to relax through another quenching method, or a chemical compound should be added to quench the triplet state.[20][42][43]

See also

- Confocal microscopy

- Fluorescence

- Fluorescence microscope

- Ground state depletion microscopy

- Laser scanning confocal microscopy

- Optical microscope

- Photoactivated localization microscopy

- Stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy

- Super-resolution microscopy

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Westphal, V.; S. O. Rizzoli; M. A. Lauterbach; D. Kamin; R. Jahn; S. W. Hell (2008). "Video-Rate Far-Field Optical Nanoscopy Dissects Synaptic Vesicle Movement". Science 320 (5873): 246–249. doi:10.1126/science.1154228. PMID 18292304. Bibcode: 2008Sci...320..246W.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Hell, S. W.; Wichmann, J. (1994). "Breaking the diffraction resolution limit by stimulated emission: Stimulated-emission-depletion fluorescence microscopy". Optics Letters 19 (11): 780–782. doi:10.1364/OL.19.000780. PMID 19844443. Bibcode: 1994OptL...19..780H.

- ↑ Klar, Thomas A.; Stefan W. Hell (1999). "Subdiffraction resolution in far-field fluorescence microscopy". Optics Letters 24 (14): 954–956. doi:10.1364/OL.24.000954. PMID 18073907. Bibcode: 1999OptL...24..954K.

- ↑ "Victor Okhonin". https://scholar.google.ca/citations?user=F-MCeeAAAAAJ&hl.

- ↑ Okhonin V.A., A method of examination of sample microstructure, Patent SU 1374922, (See also in the USSR patents database SU 1374922) priority date April 10, 1986, Published on July 30, 1991, Soviet Patents Abstracts, Section EI, Week 9218, Derwent Publications Ltd., London, GB; Class S03, p. 4. Cited by patents US 5394268 A (1993) and US RE38307 E1 (1995). From the English translation: "The essence of the invention is as follows. Luminescence is excited in a sample placed in the field of several standing light waves, which cause luminescence quenching because of stimulated transitions...".

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Blom, H.; Brismar, H. (2014). "STED microscopy: Increased resolution for medical research?". Journal of Internal Medicine 276 (6): 560–578. doi:10.1111/joim.12278. PMID 24980774.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Müller, T.; Schumann, C.; Kraegeloh, A. (2012). "STED Microscopy and its Applications: New Insights into Cellular Processes on the Nanoscale". ChemPhysChem 13 (8): 1986–2000. doi:10.1002/cphc.201100986. PMID 22374829.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Dyba, M.; Hell, S. W. (2003). "Photostability of a Fluorescent Marker Under Pulsed Excited-State Depletion through Stimulated Emission". Applied Optics 42 (25): 5123–5129. doi:10.1364/AO.42.005123. PMID 12962391. Bibcode: 2003ApOpt..42.5123D.

- ↑ Török, P.; Munro, P. R. T. (2004). "The use of Gauss-Laguerre vector beams in STED microscopy". Optics Express 12 (15): 3605–3617. doi:10.1364/OPEX.12.003605. PMID 19483892. Bibcode: 2004OExpr..12.3605T.

- ↑ Keller, J.; Schönle, A.; Hell, S. W. (2007). "Efficient fluorescence inhibition patterns for RESOLFT microscopy". Optics Express 15 (6): 3361–3371. doi:10.1364/OE.15.003361. PMID 19532577. Bibcode: 2007OExpr..15.3361K.

- ↑ S. W. Hell, Reuss, M (Jan 2010). "Birefringent device converts a standard scanning microscope into a STED microscope that also maps molecular orientation". Optics Express 18 (2): 1049–58. doi:10.1364/OE.18.001049. PMID 20173926. Bibcode: 2010OExpr..18.1049R. https://www.osapublishing.org/view_article.cfm?gotourl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.osapublishing.org%2FDirectPDFAccess%2F99FA483A-0646-B546-21FF6EC9153CCE99_194386%2Foe-18-2-1049.pdf%3Fda%3D1%26id%3D194386%26seq%3D0%26mobile%3Dno&org=.

- ↑ Wildanger, D.; B. R. Patton; H. Schill; L. Marseglia; J. P. Hadden; S. Knauer; A. Schönle; J. G. Rarity et al. (2012). "Solid Immersion Facilitates Fluorescence Microscopy with Nanometer Resolution and Sub-Ångström Emitter Localization". Advanced Materials 24 (44): OP309–OP313. doi:10.1002/adma.201203033. PMID 22968917. Bibcode: 2012AdM....24P.309W.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Klar, T. A.; S. Jakobs; M. Dyba; A. Egner; S. W. Hell (2000). "Fluorescence microscopy with diffraction resolution barrier broken by stimulated emission". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (15): 8206–8210. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.15.8206. PMID 10899992. Bibcode: 2000PNAS...97.8206K.

- ↑ Hell, Stefan W. (November 2003). "Toward fluorescence nanoscopy" (in en). Nature Biotechnology 21 (11): 1347–1355. doi:10.1038/nbt895. ISSN 1546-1696. PMID 14595362. https://www.nature.com/articles/nbt895.

- ↑ Lang, Sieber (April 2006). "The SNARE Motif Is Essential for the Formation of Syntaxin Clusters in the Plasma Membrane". Biophysical Journal 90 (8): 2843–2851. doi:10.1529/biophysj.105.079574. PMID 16443657. Bibcode: 2006BpJ....90.2843S.

- ↑ Sieber, J. J.; K. L. Willig; R. Heintzmann; S. W. Hell; T. Lang (2006). "The SNARE Motif Is Essential for the Formation of Syntaxin Clusters in the Plasma Membrane". Biophys. J. 90 (8): 2843–2851. doi:10.1529/biophysj.105.079574. PMID 16443657. Bibcode: 2006BpJ....90.2843S.

- ↑ Willig, K. I.; J. Keller; M. Bossi; S. W. Hell (2006). "STED microscopy resolves nanoparticle assemblies". New J. Phys. 8 (6): 106. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/8/6/106. Bibcode: 2006NJPh....8..106W.

- ↑ Wildanger, D.; Rittweger; Kastrup, L.; Hell, S. W. (2008). "STED microscopy with a supercontinuum laser source". Opt. Express 16 (13): 9614–9621. doi:10.1364/oe.16.009614. PMID 18575529. Bibcode: 2008OExpr..16.9614W.

- ↑ Doonet, G.; J. Keller; C. A. Wurm; S. O. Rizzoli; V. Westphal; A. Schonle; R. Jahn; S. Jakobs et al. (2007). "Two-Color Far-Field Fluorescence Nanoscopy". Biophys. J. 92 (8): L67–L69. doi:10.1529/biophysj.107.104497. PMID 17307826. Bibcode: 2007BpJ....92L..67D.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Kasper, R.; B. Harke; C. Forthmann; P. Tinnefeld; S. W. Hell; M. Sauer (2010). "Single-Molecule STED Microscopy with Photostable Organic Fluorophores". Small 6 (13): 1379–1384. doi:10.1002/smll.201000203. PMID 20521266.

- ↑ Willig, K. I.; B. Harke; R. Medda; S. W. Hell (2007). "STED microscopy with continuous wave beams". Nat. Methods 4 (11): 915–918. doi:10.1038/nmeth1108. PMID 17952088.

- ↑ Buckers, J.; D. Wildanger; G. Vicidomini; L. Kastrup; S. W. Hell (2011). "Simultaneous multi-lifetime multi-color STED imaging for colocalization analyses". Opt. Express 19 (4): 3130–3143. doi:10.1364/OE.19.003130. PMID 21369135. Bibcode: 2011OExpr..19.3130B.

- ↑ Halemani, N. D.; I. Bethani; S. O. Rizzoli; T. Lang (2010). "Structure and Dynamics of a Two-Helix SNARE Complex in Live Cells". Traffic 11 (3): 394–404. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.01020.x. PMID 20002656.

- ↑ Geumann, U.; C. Schäfer; D. Riedel; R. Jahn; S. O. Rizzoli (2010). "Synaptic membrane proteins form stable microdomains in early endosomes". Microsc. Res. Tech. 73 (6): 606–617. doi:10.1002/jemt.20800. PMID 19937745.

- ↑ Singh, H.; R. Lu; P. F. G. Rodriguez; Y. Wu; J. C. Bopassa; E. Stefani; L. ToroMitochondrion (2012). "Visualization and quantification of cardiac mitochondrial protein clusters with STED microscopy". Mitochondrion 12 (2): 230–236. doi:10.1016/j.mito.2011.09.004. PMID 21982778.

- ↑ Wurm, C. A.; D. Neumann; R. Schmidt; A. Egner; S. Jakobs (2010). "Sample Preparation for STED Microscopy". Live Cell Imaging. Methods in Molecular Biology. 591. pp. 185–199. doi:10.1007/978-1-60761-404-3_11. ISBN 978-1-60761-403-6.

- ↑ Kim, Namdoo; Kim, Hyung Jun; Kim, Younggyu; Min, Kyung Suk; Kim, Seong Keun (2016). "Direct and precise length measurement of single, stretched DNA fragments by dynamic molecular combing and STED nanoscopy". Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 408 (23): 6453–6459. doi:10.1007/s00216-016-9764-9. PMID 27457103.

- ↑ Sharma, S.; C. Santiskulvong; L. Bentolila; J. Rao; O. Dorigo; J. K. Gimzewski (2011). "Correlative nanomechanical profiling with super-resolution F-actin imaging reveals novel insights into mechanisms of cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer cells". Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine 8 (5): 757–766. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2011.09.015. PMID 22024198.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Hoopman, P.; A. Punge; S. V. Barysch; V. Westphal; J. Buchkers; F. Opazo; I. Bethani; M. A. Lauterbach et al. (2010). "Endosomal sorting of readily releasable synaptic vesicles". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 (44): 19055–19060. doi:10.1073/pnas.1007037107. PMID 20956291. PMC 2973917. Bibcode: 2010PNAS..10719055H. http://pubman.mpdl.mpg.de/pubman/item/escidoc:897590/component/escidoc:2213773/897590.pdf.

- ↑ Opazo, F.; A. Punge; J. Buckers; P. Hoopmann; L. Kastrup; S. W. Hell; S. O. Rizzoli (2010). "Limited intermixing of synaptic vesicle components upon vesicle recycling". Traffic 11 (6): 800–812. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0854.2010.01058.x. PMID 20230528.

- ↑ Eggeling, C.; Ringemann, C.; Medda, R.; Schwarzmann, G.; Sandhoff, K.; Polyakova, S.; Belov, V. N.; Hein, B. et al. (2009). "Direct observation of the nanoscale dynamics of membrane lipids in a living cell". Nature 457 (7233): 1159–1162. doi:10.1038/nature07596. PMID 19098897. Bibcode: 2009Natur.457.1159E.

- ↑ Willig, K. I.; R. R. Kellner; R. Medda; B. Heln; S. Jakobs; S. W. Hell (2006). "Nanoscale resolution in GFP-based microscopy". Nat. Methods 3 (9): 721–723. doi:10.1038/nmeth922. PMID 16896340.

- ↑ Hein, B.; K. I. Willig; S. W. Hell (2008). "Stimulated emission depletion (STED) nanoscopy of a fluorescent protein-labeled organelle inside a living cell". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 (38): 14271–14276. doi:10.1073/pnas.0807705105. PMID 18796604. Bibcode: 2008PNAS..10514271H.

- ↑ Kleine-Vehn, J.; Wabnik, K.; Martiniere, A.; Langowski, L.; Willig, K.; Naramoto, S.; Leitner, J.; Tanaka, H. et al. (2011). "Recycling, clustering, and endocytosis jointly maintain PIN auxin carrier polarity at the plasma membrane". Mol. Syst. Biol. 7: 540. doi:10.1038/msb.2011.72. PMID 22027551.

- ↑ Pellett, P. A.; X. Sun; T. J. Gould; J. E. Rothman; M. Q. Xu; I. R. Corréa; J. Bewersdorf (2011). "Two-color STED microscopy in living cells". Biomed. Opt. Express 2 (8): 2364–2371. doi:10.1364/boe.2.002364. PMID 21833373.

- ↑ Steffens, Heinz; Wegner, Waja; Willig, Katrin I. (2020-03-01). "In vivo STED microscopy: A roadmap to nanoscale imaging in the living mouse". Methods 174: 42–48. doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2019.05.020. ISSN 1095-9130. PMID 31132408.

- ↑ Steffens, Heinz; Mott, Alexander C.; Li, Siyuan; Wegner, Waja; Švehla, Pavel; Kan, Vanessa W. Y.; Wolf, Fred; Liebscher, Sabine et al. (2021). "Stable but not rigid: Chronic in vivo STED nanoscopy reveals extensive remodeling of spines, indicating multiple drivers of plasticity". Science Advances 7 (24). doi:10.1126/sciadv.abf2806. ISSN 2375-2548. PMID 34108204. Bibcode: 2021SciA....7.2806S.

- ↑ Wegner, Waja; Steffens, Heinz; Gregor, Carola; Wolf, Fred; Willig, Katrin I. (2021-09-15). "Environmental enrichment enhances patterning and remodeling of synaptic nanoarchitecture revealed by STED nanoscopy" (in en). bioRxiv: 2020.10.23.352195. doi:10.1101/2020.10.23.352195. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.10.23.352195v2.

- ↑ Westphal, V.; M. A. Lauterbach; A. Di Nicola; S. W. Hell (2007). "Dynamic far-field fluorescence nanoscopy". New J. Phys. 9 (12): 435. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/9/12/435. Bibcode: 2007NJPh....9..435W.

- ↑ Lauterbach, M.A.; Chaitanya K. Ullal; Volker Westphal; Stefan W. Hell (2010). "Dynamic Imaging of Colloidal-Crystal Nanostructures at 200 Frames per Second". Langmuir 26 (18): 14400–14404. doi:10.1021/la102474p. PMID 20715873.

- ↑ Hotta, J. I.; E. Fron; P. Dedecker; K. P. F. Janssen; C. Li; K. Mullen; B. Harke; J. Buckers et al. (2010). "Spectroscopic Rationale for Efficient Stimulated-Emission Depletion Microscopy Fluorophores". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132 (14): 5021–5023. doi:10.1021/ja100079w. PMID 20307062.

- ↑ Vogelsang, J.; R. Kasper; C. Sreinhauer; B. Person; M. Heilemann; M. Sauer; P. Tinnedeld (2008). "Ein System aus Reduktions‐ und Oxidationsmittel verringert Photobleichen und Blinken von Fluoreszenzfarbstoffen". Angew. Chem. 120 (29): 5545–5550. doi:10.1002/ange.200801518.

- ↑ Vogelsang, J.; R. Kasper; C. Sreinhauer; B. Person; M. Heilemann; M. Sauer; P. Tinnedeld (2008). "A Reducing and Oxidizing System Minimizes Photobleaching and Blinking of Fluorescent Dyes". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47 (29): 5465–5469. doi:10.1002/anie.200801518. PMID 18601270.

External links

- Overview at the Department of NanoBiophotonics at the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry.

- Brief summary of the RESOLFT equations developed by Stefan Hell.

- Stefan Hell lecture: Super-Resolution: Overview and Stimulated Emission Depletion (STED) Microscopy

- Light Microscopy: An ongoing contemporary revolution (Introductory Review)

|