Biology:Rock parrot

| Rock parrot | |

|---|---|

| |

| At William Bay, Western Australia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Family: | Psittaculidae |

| Genus: | Neophema |

| Species: | N. petrophila

|

| Binomial name | |

| Neophema petrophila (Gould, 1841)

| |

| |

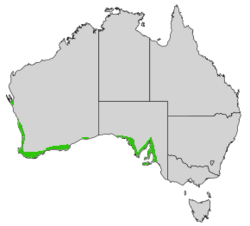

| Rock parrot range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Euphema petrophila, Gould, 1841 | |

The rock parrot (Neophema petrophila) is a species of grass parrot native to Australia . Described by John Gould in 1841, it is a small parrot 22–24 cm (8 3⁄4–9 1⁄2 in) long and weighing 50–60 g (1 3⁄4–2 oz) with predominantly olive-brown upperparts and more yellowish underparts. Its head is olive with light blue forecheeks and lores, and a dark blue frontal band line across the crown with lighter blue above and below. The sexes are similar in appearance, although the female tends to have a duller frontal band and less blue on the face. The female's call also tends to be far louder and more shrill than the male's. Two subspecies are currently recognised.

Rocky islands and coastal dune areas are the preferred habitats for this species, which is found from Lake Alexandrina in southeastern South Australia westwards across coastal South and Western Australia to Shark Bay. Unlike other grass parrots, it nests in burrows or rocky crevices mostly on offshore islands such as Rottnest Island. Seeds of grasses and succulent plants form the bulk of its diet. The species has suffered in the face of feral mammals; although its population is declining, it is considered to be a least-concern species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Taxonomy

The rock parrot was described by the English ornithologist John Gould in 1841 as Euphema petrophila,[2] its specific name petrophila derived from the Ancient Greek πετρος (petros) 'rock' and φιλος (philos) 'loving'.[3] The author's specimen was one of fifty new bird species presented before the Zoological Society of London.[2] The rock parrot was included in Gould's fifth volume of Birds of Australia, using specimens obtained at Port Lincoln in South Australia and from collector John Gilbert in Western Australia. Gilbert stated that at the time of English colonisation the species was common on cliff faces on offshore islands, including Rottnest, near the western port of Fremantle, the nests in almost inaccessible locations.[4]

The Italian ornithologist Tommaso Salvadori defined the new genus Neophema in 1891, placing the rock parrot within it and giving it its current scientific name Neophema petrophila.[5] Within the grass parrot genus Neophema, it is one of four species classified in the subgenus Neonanodes.[6] Analysis of mitochondrial DNA published in 2021 indicated the rock parrot is most closely related to the blue-winged parrot, their mutual ancestors most likely diverging between 0.7 and 3.3 million years ago.[7]

A burrow-nester, the rock parrot has evolved from a lineage of tree-nesting ancestors. The biologist Donald Brightsmith has proposed that several lineages of parrots and trogons switched to nesting in burrows to avoid tree-living mammalian predators that evolved and proliferated in the late Oligocene to early Miocene (30–20 million years ago).[8]

Two subspecies are recognised by the International Ornithologists' Union: subspecies petrophila from Western Australia and subspecies zietzi from South Australia,[9] the latter described by Gregory Mathews in 1912 from the Sir Joseph Banks Group in Spencer Gulf,[10] after the Assistant Director of the South Australian Museum Amandus Heinrich Christian Zietz.[11] The authors of the online edition of the Handbook of the Birds of the World do not regard this as distinct.[12]

"Rock parrot" has been designated as the official common name for the species by the International Ornithologists' Union (IOC).[9] Gilbert reported the Swan River colonists called it the rock parrakeet, and he labelled it the rock grass-parrakeet.[4] It is also known as rock elegant parrot.[13]

Description

Ranging from 22 to 24 cm (8 3⁄4 to 9 1⁄2 in) long with a 33–34 cm (13–13 1⁄2 in) wingspan, the rock parrot is a small and slightly built parrot weighing around 50–60 g (1 3⁄4–2 oz). The sexes are similar in appearance, with predominantly olive-brown upperparts including the head and neck, and more yellowish underparts. A dark blue band runs across the upper forehead between the eyes, bordered above by a thin light blue line that extends behind the eyes and below by a thicker light blue band across the lower forehead. The forecheeks and lores are light blue. In the adult female, the dark blue band is slightly duller and there is less blue on the face. The wings are predominantly olive, and display a two-toned blue leading edge when folded. The primary flight feathers are black with dark blue edges, while the inner wing feathers are olive. The tail is turquoise edged with yellow on its upper surface. The breast, flanks and abdomen are more olive-yellow, becoming more yellow towards the vent.[14] The bases of the feathers on the head and body are grey, apart from those on the nape, which are white. These are not normally visible.[15] The bill is black with pale highlights on both mandibles, the cere is black. The orbital eye-ring is grey and the iris is dark brown. The legs and feet are dark grey, with a pink tinge on the soles and rear of the tarsi.[14] Subspecies zietzi has paler and more yellowish plumage overall, though is of a similar size. Its plumage darkens with wear, and may be indistinguishable from the nominate subspecies when old.[16]

Juveniles are a duller, darker olive all over and either lack or have indistinct blue frontal bands. Their primary flight feathers have yellow fringes.[17] They have a yellowish or orange bill initially, which turns brown by ten weeks of age.[14] Juvenile females have pale oval spots on their fourth to eighth primary flight feathers.[17] They moult from juvenile to immature plumage when a few months old.[15] Immature males and females closely resemble adults, though have worn-looking flight feathers.[17] They then moult into adult plumage when they are twelve months old.[15]

The rock parrot can be confused with the elegant parrot in Western Australia, or blue-winged parrot in South Australia, both of which have similar (though brighter) olive plumage. These two species also have yellow lores and the latter has much bluer wings. The orange-bellied parrot has brighter green plumage and green-yellow lores.[14]

Distribution and habitat

The rock parrot occurs along the coastline of southern Australia in two disjunct populations. In South Australia, it is found as far east as Lake Alexandrina and Goolwa, though is rare in the Fleurieu Peninsula. It was reported further east at Baudin Rocks near Robe, South Australia, in the 1930s, though not since. It is more common along the coastline of the northeastern Gulf St Vincent between Lefevre Peninsula and Port Wakefield, and Yorke Peninsula across Investigator Strait to Kangaroo Island, the Gambier Islands, and the Eyre Peninsula from Arno Bay to Ceduna and nearby Nuyts Archipelago. In Western Australia it is found from the Eyre Bird Observatory in the east, along the southern and western coastline to Jurien Bay Marine Park, becoming less common further north to Kalbarri and Shark Bay. Historically, it has been reported from Houtman Abrolhos.[18] The rock parrot is generally sedentary, though birds may disperse over 160 km (100 mi) after breeding. Some do remain on the offshore islands where they breed year-round.[19]

The rock parrot is almost always encountered within a few hundred metres of the coast down to the high-water mark, though may occasionally follow estuaries a few kilometres inland. The preferred habitat is bare rocky ground or low coastal shrubland composed of plants such as pigface (Disphyma crassifolium clavellatum), saltbush (Atriplex) or nitre bush (Nitraria billardierei). The species has also been found in sand dunes and saltmarsh, and under sprinklers on the golf course on Rottnest Island. They tend to avoid farmland.[18]

Behaviour

Rock parrots are encountered in pairs or small groups, although they may congregate into larger flocks of up to 100 birds. They can form mixed flocks with elegant or blue-winged parrots. Mostly terrestrial, rock parrots at times perch on rocks or shrubs, and can take cover among large rocks. Generally quiet and unobtrusive, they make a two-syllabled zitting contact call in flight or when feeding. The alarm call is similar but louder.[18]

Breeding

The breeding habits of the rock parrot are not well-known.[20] It mostly breeds on offshore islands, including the Sir Joseph Banks Group and Nuyts Archipelago in South Australia, and Recherche Archipelago, Eclipse Island, Rottnest Island and islands in Jurien Bay. On the mainland, nesting has been reported at Point Malcolm near Israelite Bay and Margaret River in Western Australia.[18]

Rock parrots are monogamous, the breeding pairs maintaining fidelity throughout their lives, although an individual may seek a new mate if the previous one dies.[21] Breeding takes place from August to December. At the beginning of the breeding season, rock parrots become more active, the males calling more often. The male courts the female by moving towards her in an upright posture, bobbing his head and calling. The female responds by performing a begging call for him to feed her, which he does with some regurgitated food. This has been observed to continue through the incubation period in captivity.[21]

The nesting site is under rocks or in crevices or burrows, which may be covered by plants such as pigface,[18] or heart-shaped noon flower (Aptenia cordifolia). They may re-use burrows of wedge-tailed shearwaters (Ardenna pacifica) or white-faced storm petrels (Pelagodroma marina). Regardless of location, nests are well-hidden and hard to access; the depth of the nest has been measured as 10–91 cm (4–36 in) in crevices, approximately 15 cm (6 in) under ledges, and 91–122 cm (36–48 in) for reused seabird burrows.[20] Rock parrots can nest in considerable numbers at some locations, with nests metres apart.[21] The clutch consists of three to six round or oval dull to glossy white eggs, each of which is generally 24 to 25 mm (1.0 in) long by 19 to 20 mm (0.8 in) wide.[22] Gilbert's local indigenous guides reported that nests were found to contain seven to eight white eggs.[4] Eggs are laid at an interval of two to four days, and a second brood may take place in favourable years. The female alone incubates the clutch, over a period of 18 to 21 days, and is fed by the male during this time.[15]

The chicks are born helpless and blind,[15] their salmon-pink skin covered in pale grey down.[17] By day eight they open their eyes, and are well-covered in grey down with pin feathers emerging from their wings on day nine and their down is dark grey. They have well-developed wing and tail feathers by day 21 and are almost fully covered in feathers by day 28. They fledge (leave the nest) at around 30 days of age in the wild and up to 39 days of age in captivity. Breeding success rates in the wild are unknown.[15]

Feeding

Foraging takes place in the early morning and late afternoon, with a rest during the heat of the day. Birds forage in pairs or small groups, though up to 200 individuals may gather at an abundant food or water source.[21] They generally forage on the ground, and can be approached easily while feeding, moving a short distance behind a tussock or rock if observers come too close.[18]

Rock parrots eat seeds of several species of grass (Poaceae), including common wild oat (Avena fatua), wheat (Triticum aestivum), hare's tail (Lagurus ovatus), and Australian brome (Bromus arenarius), and rush (Cyperaceae), as well as shrubs and particularly succulent plants of the family Aizoaceae, such as pigface, and Carpobrotus rossii, and the introduced species Carpobrotus aequilaterus and Mesembryanthemum crystallinum. Daisy species' seed consumed include coastal daisybush (Olearia axillaris), variable groundsel (Senecio pinnatifolius), and the introduced capeweed (Arctotheca calendula), South African beach daisy (Arctotheca populifolia) and prickly sow-thistle (Sonchus asper). Brassicaceae include the native leafy peppercress (Lepidium foliosum) and introduced European searocket (Cakile maritima). Chenopod species include Atriplex, shrubby glasswort (Tecticornia arbuscula), ruby saltbush (Enchylaena tomentosa), berry saltbush (Chenopodium baccatum), and other species such as pink purslane (Calandrinia calyptrata), species of Acacia, Acaena and Myoporum, the coastal beard-heath (Leucopogon parviflorus), common sea heath (Frankenia pauciflora), and coastal jugflower (Adenanthos cuneatus).[21]

Conservation status

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists the rock parrot as a species of least concern, though the overall population is decreasing. It is threatened by feral animals (mainly cats and foxes) and climate change.[1] Feral cats were cited after the species vanished from the vicinity of Albany, Western Australia, in 1905, but the species was found again in 1939.[19]

On Rottnest Island, the species was common up to at least 1929. On a survey of the island in 1965, Western Australian biologist Glen Storr found it to have become rare and concluded this was due to young birds being taken for the pet trade.[23] This occurred mainly in the 1940s and 1950s before being closed down in the 1970s.[19] The population did not recover,[23] and by 2012 had dropped to seven birds. The use of artificial nesting sites and a breeding program has seen some success and a rise in numbers.[24] Birds on the island are being banded and the public urged to get involved.[25]

Like most species of parrot, the rock parrot is protected by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) with its placement on the Appendix II list of vulnerable species, which makes the import, export and trade of listed wild-caught animals illegal.[26]

Aviculture

The species is infrequently kept in captivity and there are few records of successful breeding. The plumage of this Neophema species is duller than others and they have a reputation as passive and uninteresting caged specimens. Differentiating the sexes presents difficulties to parrot enthusiasts, with no reliable way to easily sex the species. The rock parrot, also known as the rock grass-parakeet in the bird trade, may be a more desirable specimen when kept as part of a colony, provided with logs simulating tree hollows and fed on Mesembryanthemum and Carpobrotus species.[27]

The parrot may become obese, unwell or infertile by overindulgence in sunflower seed, and aviculturists recommend reducing the availability of these in the aviary.[27]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 BirdLife International (2016). "Neophema petrophila". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22685200A93063016. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22685200A93063016.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22685200/93063016. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Gould, John (1841). "Proceedings of meeting of Zoological Society of London, Nov. 10, 1840". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1840: 147–151 [148]. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/30571587.

- ↑ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1980). A Greek–English Lexicon (Abridged ed.). United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-910207-5. https://archive.org/details/lexicon00lidd.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Gould, John (1848). The Birds of Australia. 5. London: Printed by R. and J. E. Taylor; pub. by the author. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/48401091.

- ↑ Salvadori, Tommaso (1891). Catalogue of the Birds in the British Museum. 20: Catalogue of the Psittaci, or Parrots. London, United Kingdom: British Museum. pp. 574–575. https://archive.org/stream/catalogueofbirds30brit#page/574/mode/2up.

- ↑ Lendon 1973, p. 253.

- ↑ Hogg, Carolyn J.; Morrison, Caitlin; Dudley, Jessica S.; Alquezar-Planas, David E.; Beasley-Hall, Perry G.; Magrath, Michael J. L.; Ho, Simon Y. W.; Lo, Nathan et al. (2021-06-26). "Using phylogenetics to explore interspecies genetic rescue options for a critically endangered parrot". Conservation Science and Practice (Wiley) 3 (9). doi:10.1111/csp2.483. ISSN 2578-4854. Bibcode: 2021ConSP...3E.483H.

- ↑ Brightsmith, Donald J. (2005). "Competition, predation and nest niche shifts among tropical cavity nesters: phylogeny and natural history evolution of parrots (Psittaciformes) and trogons (Trogoniformes)". Journal of Avian Biology 36 (1): 64–73. doi:10.1111/j.0908-8857.2005.03310.x.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Gill, Frank; Donsker, David, eds (2017). "Parrots & cockatoos". World Bird List Version 7.1. International Ornithologists' Union. http://www.worldbirdnames.org/bow/parrots/.

- ↑ Mathews, Gregory (1912). "A Reference-List to the Birds of Australia". Novitates Zoologicae 18: 171–455 [278]. doi:10.5962/bhl.part.1694. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/3109934.

- ↑ Jobling, J. A. (2019). "Key to Scientific Names in Ornithology". in del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J. et al.. Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions. https://www.hbw.com/dictionary/definition/zietzi.

- ↑ Collar, N.; Boesman, P. (2019). "Rock Parrot (Neophema petrophila)". in del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J. et al.. Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions. https://www.hbw.com/node/54526.

- ↑ Gray, Jeannie; Fraser, Ian (2013). Australian Bird Names: A Complete Guide. Collingwood, Victoria: CSIRO Publishing. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-643-10471-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=W1TCqHVWQp0C&pg=PT143.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Higgins 1999, p. 549.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 Higgins 1999, p. 554.

- ↑ Higgins 1999, p. 556.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Higgins 1999, p. 555.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 Higgins 1999, p. 550.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Higgins 1999, p. 551.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Higgins 1999, p. 553.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 Higgins 1999, p. 552.

- ↑ Higgins 1999, pp. 553–554.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Saunders, Denis A.; de Rebeira, C. P. (2009). "A case study of the conservation value of a small tourist resort island: Birds of Rottnest Island, Western Australia 1905–2007". Pacific Conservation Biology 15: 11–31. doi:10.1071/PC090011.

- ↑ Sansom, James; Blythman, Mark; Dadour, Lucy; Rayner, Kelly (2019). "Deployment of novel nest-shelters to increase nesting attempts in a small population of Rock Parrots Neophema petrophila". Australian Field Ornithology 36: 74–78. doi:10.20938/afo36074078.

- ↑ Acott, Kent (27 December 2017). "Rottnest Island's native rock parrot saved from brink of extinction". The West Australian. https://thewest.com.au/news/rottnest/rottnest-islands-native-rock-parrot-saved-from-brink-of-extinction-ng-b88696158z.

- ↑ "Appendices I, II and III". Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). 22 May 2009. http://www.cites.org/eng/app/appendices.shtml.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Shephard, Mark (1989). Aviculture in Australia: Keeping and Breeding Aviary Birds. Prahran, Victoria: Black Cockatoo Press. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-0-9588106-0-9.

Cited texts

- Higgins, P.J. (1999). Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds. Volume 4: Parrots to Dollarbird. Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-553071-1.

- Lendon, Alan H. (1973). Australian Parrots in Field and Aviary. Sydney, New South Wales: Angus & Robertson. ISBN 978-0-207-12424-2.

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q1125779 entry

|