Biology:Cytoplasmic streaming

File:Cytoplasmic streaming.webm

Cytoplasmic streaming, also called protoplasmic streaming and cyclosis, is the flow of the cytoplasm inside the cell, driven by forces from the cytoskeleton.[1] It is likely that its function is, at least in part, to speed up the transport of molecules and organelles around the cell. It is usually observed in large plant and animal cells, greater than approximately 0.1 mm[vague]. In smaller cells, the diffusion of molecules is more rapid, but diffusion slows as the size of the cell increases, so larger cells may need cytoplasmic streaming for efficient function.[1]

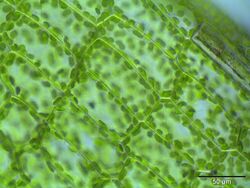

The green alga genus Chara possesses some very large cells, up to 10 cm in length,[2] and cytoplasmic streaming has been studied in these large cells.[3]

Cytoplasmic streaming is strongly dependent upon intracellular pH and temperature. It has been observed that the effect of temperature on cytoplasmic streaming created linear variance and dependence at different high temperatures in comparison to low temperatures.[4] This process is complicated, with temperature alterations in the system increasing its efficiency, with other factors such as the transport of ions across the membrane being simultaneously affected. This is due to cells homeostasis depending upon active transport which may be affected at some critical temperatures.

In plant cells, chloroplasts may be moved around with the stream, possibly to a position of optimum light absorption for photosynthesis. The rate of motion is usually affected by light exposure, temperature, and pH levels.

The optimal pH at which cytoplasmic streaming is highest, is achieved at neutral pH and decreases at both low and high pH.

The flow of cytoplasm may be stopped by:

- Adding Lugol's iodine solution

- Adding Cytochalasin D (dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide)

Mechanism for cytoplasmic flow around a central vacuole

What is clearly visible in plants cells which exhibit cytoplasmic streaming is the motion of the chloroplasts moving with the cytoplasmic flow. This motion results from fluid being entrained by moving motor molecules of the plant cell.[5] Myosin filaments connect cell organelles to actin filaments. These actin filaments are generally attached to the chloroplasts and/or membranes of plant cells.[5] As the myosin molecules "walk" along the actin filaments dragging the organelles with them, the cytoplasmic fluid becomes entrained and is pushed/pulled along.[5] Cytoplasmic flow rates can range between 1 and 100 micron/sec.[5][6]

Cytoplasmic flow in Chara corallina

Chara corallina exhibits cyclic cytoplasmic flow around a large central vacuole.[5] The large central vacuole is one of the largest organelles in a plant cell and is generally used for storage.[7] In Chara coralina, cells can grow up to 10 cm long and 1 mm in diameter.[5] The diameter of the vacuole can occupy around 80% of the cell's diameter.[8] Thus for a 1 mm diameter cell, the vacuole can have a diameter of 0.8 mm, leaving only a path width of about 0.1 mm around the vacuole for cytoplasm to flow. The cytoplasm flows at a rate of 100 microns/sec, the fastest of all known cytoplasmic streaming phenomena.[5]

Characteristics

The flow of the cytoplasm in the cell of Chara corallina is belied by the "barber pole" movement of the chloroplasts.[5] Two sections of chloroplast flow are observed with the aid of a microscope. These sections are arranged helically along the longitudinal axis of the cell.[5] In one section, the chloroplasts move upward along one band of the helix, while in the other, the chloroplasts move downwardly.[5] The area between these sections are known as indifferent zones. Chloroplasts are never seen to cross these zones,[5] and as a result it was thought that cytoplasmic and vacuolar fluid flow are similarly restricted, but this is not true. First, Kamiya and Kuroda, experimentally determined that cytoplasmic flow rate varies radially within the cell, a phenomenon not clearly depicted by the chloroplast movement.[9] Second, Raymond Goldstein and others developed a mathematical fluid model for the cytoplasmic flow which not only predicts the behavior noted by Kamiya and Kuroda,[5] but predicts the trajectories of cytoplasmic flow through indifferent zones. The Goldstein model ignores the vacuolar membrane, and simply assumes that shear forces are directly translated to the vacuolar fluid from the cytoplasm. The Goldstein model predicts there is net flow toward one of the indifferent zones from the other.[5] This actually is suggested by the flow of the chloroplasts. At one indifferent zone, the section with the chloroplasts moving at a downward angle will be above the chloroplasts moving at an upward angle. This section is known as the minus different zone (IZ-). Here, if each direction is broken into components in the theta (horizontal) and z (vertical) directions, the sum of these components oppose each other in the z direction, and similarly diverges in theta direction.[5] The other indifferent zone has the upwardly angled chloroplast movement on top and is known as the positive indifferent zone (IZ+). Thus, while the z directional components oppose each other again, the theta components now converge.[5] The net effect of the forces is cytoplasmic/vacuolar flow moves from the minus indifferent zone to the positive indifferent zone.[5] As stated, these directional components are suggested by chloroplast movement, but are not obvious. Further, the effect of this cytoplasmic/vacuolar flow from one indifferent zone to the other demonstrates that cytoplasmic particles do cross the indifferent zones even if the chloroplasts at the surface do not. Particles, as they rise in the cell, spiral around in a semicircular manner near the minus indifferent zone, cross one indifferent zone, and end up near a positive indifferent zone.[5] Further experiments on the Characean cells support of the Goldstein model for vacuolar fluid flow.[8] However, due to the vacuolar membrane (which was ignored in the Goldstein model), the cytoplasmic flow follows a different flow pattern. Further, recent experiments have shown that the data collected by Kamiya and Kuroda which suggested a flat velocity profile in the cytoplasm are not fully accurate.[8] Kikuchi worked with Nitella flexillis cells, and found an exponential relationship between fluid flow velocity and distance from cell membrane.[8] Although this work is not on Characean cells, the flows between Nitella flexillis and Chara coralina are visually and structurally similar.[8]

Benefits of cytoplasmic flow in Chara corallina and Arabidopsis thaliana

Enhanced nutrient transport and better growth

The Goldstein model predicts enhanced transport (over transport characterized by strictly longitudinal cytoplasmic flow) into the vacuolar cavity due to the complicated flow trajectories arising from the cytoplasmic streaming.[5] Although, a nutrient concentration gradient would result from longitudinally uniform concentrations and flows, the complicated flow trajectories predicted produce a larger concentration gradient across the vacuolar membrane.[5] By Fick's laws of diffusion, it is known that larger concentration gradients lead to larger diffusive flows.[10] Thus, the unique flow trajectories of the cytoplasmic flow in Chara coralina lead to enhanced nutrient transport by diffusion into the storage vacuole. This allows for higher concentrations of nutrients inside the vacuole than would be allowed by strictly longitudinal cytoplasmic flows. Goldstein also demonstrated the faster the cytoplasmic flow along these trajectories, the larger the concentration gradient that arises, and the larger diffusive nutrient transport into the storage vacuole that occurs. The enhanced nutrient transport into the vacuole leads to striking differences in growth rate and overall growth size.[6] Experiments have been performed in Arabidopsis thaliana. Wild type versions of this plant exhibit cytoplasmic streaming due to the entrainment of fluid similar to Chara coralina, only at slower flow rates.[6] One experiment removes the wild type myosin motor molecule from the plant and replaces it with a faster myosin molecule which moves along the actin filaments at 16 microns/sec. In another set of plants, the myosin molecule is replaced with the slower homo sapiens Vb myosin motor molecule. Human myosin Vb only moves at a rate of .19 microns/sec. Resulting cytoplasmic flows rates are 4.3 microns/sec for the wild type and 7.5 microns/sec for the plants implanted with the rapidly moving myosin protein. The plants implanted with human myosin Vb do not exhibit continuous cytoplasmic streaming. The plants are then allowed to grow under similar conditions. Faster cytoplasmic rates produced larger plants with larger and more abundant leaves.[6] This suggests that the enhanced nutrient storage demonstrated by the Goldstein model allows for plants to grow larger and faster.[5][6]

Increased photosynthetic activity in Chara corallina

Photosynthesis converts light energy into chemical energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP).[11] This occurs in the chloroplasts of plants cells. Light photons interact with various intermembrane proteins of the cholorplast to accomplish this. However, these proteins can become saturated with photons, making them unable to function until the saturation is alleviated. This is known as the Kautsky effect and is a cause of inefficiency on the ATP production mechanism. Cytoplasmic streaming in Chara corallina, however, enables chloroplasts to move around the stem of the plant. Thus, the chloroplasts move into lighted regions and shaded regions.[11] This intermittent exposure to photons due to cytoplasmic streaming actually increases the photosynthetic efficiency of chloroplasts.[11] Photosynthetic activity is generally assessed using chlorophyll fluorescence analysis.

Gravisensing in Chara corallina

Gravisensing is the ability to sense the gravitational force and react to it. Many plants use gravisensing to direct growth. For example, depending on root orientation, amyloplasts will settle within a plant cell differently. These different settling patterns cause the protein auxin to be distributed differently within the plant. This differences in the distribution pattern direct roots to grow downward or outward. In most plants, gravisensing requires a coordinated multi-cellular effort, but in Chara corallina, one cell detects gravity and responds to it.[12] The barber pole chloroplast motion resulting from cytoplasmic streaming has one flow upward and another downward.[5] The downward motion of the chloroplasts moves a bit faster than the upward flow producing a ratio of speeds of 1.1.[5][12] This ratio is known as the polar ratio and depends on the force of gravity.[12] This increase in speed is not a direct result of the force of gravity, but an indirect result. Gravity causes the plant protoplast to settle within the cell wall. Thus, the cell membrane is put into tension at the top, and into compression at the bottom. The resulting pressures on the membrane allow for gravisensing which result in the differing speeds of cytoplasmic flow observed in Chara coralina. This gravitational theory of gravisensing is directly opposed to the statolith theory exhibited by the settling of amyloplasts.[12]

Natural emergence of cytoplasmic streaming in Chara corallina

Cytoplasmic streaming occurs due to the motion of organelles attached to actin filaments via myosin motor proteins.[5] However, in Chara corallina, the organization of actin filaments is highly ordered. Actin is a polar molecule, which means that myosin only moves in one direction along the actin filament.[3] Thus, in Chara corallina, where motion of the chloroplasts and the myosin molecule follow a barber pole pattern, the actin filaments must all be similarly oriented within each section.[3] In other words, the section where the chloroplasts move upward will have all of the actin filaments oriented in the same upward direction, and the section where the chloroplasts move downward will have all the actin filaments oriented in the downward direction. This organization emerges naturally from basic principles. With basic, realistic assumptions about the actin filament, Woodhouse demonstrated that the formation of two sets of actin filament orientations in a cylindrical cell is likely. His assumptions included a force keeping the actin filament in place once set down, an attractive force between filaments leading them to be more likely align as a filament already in place, and a repulsive force preventing alignment perpendicular to the length of the cylindrical cell.[3] The first two assumptions derive from the molecular forces within the actin filament, while the last assumption was made due to the actin molecule's dislike of curvature.[3] Computer simulations run with these assumptions with varying parameters for the assumptive forces almost always leads to highly ordered actin organizations.[3] However, no order was as organized and consistent as the barber pole pattern found in nature, which suggests this mechanism plays role, but is not wholly responsible for the organization of actin filaments in Chara corallina.

Cytoplasmic flows created by pressure gradients

Cytoplasmic streaming in some species is caused by pressure gradients along the length of the cell.

In Physarum polycephalum

Physarum polycephalum is a single-celled protist, belonging to a group of organisms informally referred to as 'slime molds'. Biological investigations into the myosin and actin molecules in this amoeboid have demonstrated striking physical and mechanistic similarities to human muscle myosin and actin molecules. Contraction and relaxation of these molecules leads to pressure gradients along the length of the cell. These contractions force cytoplasmic fluid in one direction and contributes to growth.[13] It has been demonstrated that while the molecules are similar to those in humans, the molecule blocking the binding site of myosin to actin is different. While, in humans, tropomyosin covers the site, only allowing contraction when calcium ions are present, in this amoeboid, a different molecule known as calmodulin blocks the site, allowing relaxation in the presence of high calcium ion levels.[13]

In Neurospora crassa

Neurospora crassa is a multicellular fungus with many off shooting hyphae. Cells can be up to 10 cm long, and are separated by a small septum.[14] Small holes in the septum allow cytoplasm and cytoplasmic contents to flow from cell to cell. Osmotic pressure gradients occur through the length of the cell to drive this cytoplasmic flow. Flows contribute to growth and the formation of cellular subcompartments.[14][15]

Contribution to growth

Cytoplasmic flows created through osmotic pressure gradients flow longitudinally along the fungal hyphae and crash into the end causing growth. It has been demonstrated that the greater pressure at the hyphal tip corresponds to faster growth rates. Longer hyphae have greater pressure differences along their length allowing for faster cytoplasmic flow rates and larger pressures at the hyphal tip.[14] This is why longer hyphae grow faster than shorter ones. Tip growth increases as cytoplasmic flow rate increases over a 24-hour period until a max rate of 1 micron/second growth rate is observed.[14] Offshoots from the main hyphae are shorter and have slower cytoplasmic flow rates and correspondingly slower growth rates.[14]

Formation of cellular subcompartments

Cytoplasmic flow in Neurospora crassa carry microtubules. The presence of microtubules create interesting aspects to the flow. Modelling the fungal cells as a pipe separated at regular points with a septum with a hole in the center should produce very symmetrical flow. Basic fluid mechanics suggest that eddies should form both before and after each septum.[16] However, eddies only form before the septum in Neurospora crassa. This is because when microtubules enter the septal hole, they are arranged parallel to flow and contribute very little to flow characteristics, however, as the exit the septal hole, the orient themselves perpendicular to flow, slowing acceleration, and preventing eddy formation.[14] The eddies formed just before the septum allow for the formation of subcompartments where nuclei spotted with special proteins aggregate.[14] These proteins, one of which is called SPA-19, contribute to septum maintenance. Without it, the septum would degrade and the cell would leak large amounts of cytoplasm into the neighboring cell leading to cell death.[14]

In mouse oocytes

In many animal cells, centrioles and spindles keep nuclei centered within a cell for mitotic, meiotic, and other processes. Without such a centering mechanism, disease and death can result. While mouse oocytes do have centrioles, they play no role in nucleus positioning, yet, the nucleus of the oocyte maintains a central position. This is a result of cytoplasmic streaming.[17] Microfilaments, independent of microtubules and myosin 2, form a mesh network throughout the cell. Nuclei, positioned in non-centered cell locations, have been demonstrated to migrate distances greater than 25 microns to the cell center. They will do this without going off course by more than 6 microns when the network is present.[17] This network of microfilaments has organelles bound to it by the myosin Vb molecule.[17] Cytoplasmic fluid is entrained by the motion of these organelles, however, no pattern of directionality is associated with the movement of the cytoplasm. In fact, the motion has been demonstrated to fulfill Brownian motion characteristics. For this reason, there is some debate as to whether this should be called cytoplasmic streaming. Nonetheless, directional movement of organelles does result from this situation. Since the cytoplasm fills the cell, it is geometrically arranged into the shape of a sphere. As the radius of a sphere increases, surface area increases. Further, the motion in any given direction is proportional to the surface area. So thinking of the cell as a series of concentric spheres, it is clear that spheres with larger radii produce a greater amount of movement than spheres with smaller radii. Thus, the movement toward the center is greater than the movement away from the center, and net movement pushing the nucleus towards a central cellular location exists. In other words, the random motion of the cytoplasmic particles create a net force toward the center of the cell.[17] Additionally, the increased motion with the cytoplasm reduces cytoplasmic viscosity allowing the nucleus to move more easily within the cell. These two factors of the cytoplasmic streaming center the nucleus in the oocyte cell.[17]

See also

- Biology:Amoeboid movement – Mode of locomotion in eukaryotic cells

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "A physical perspective on cytoplasmic streaming". Interface Focus 5 (4): 20150030. August 2015. doi:10.1098/rsfs.2015.0030. PMID 26464789.

- ↑ Beilby, Mary J.; Casanova, Michelle T. (2013-11-19). The Physiology of Characean Cells. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-642-40288-3.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 "Cytoplasmic streaming in plant cells emerges naturally by microfilament self-organization". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110 (35): 14132–7. August 2013. doi:10.1073/pnas.1302736110. PMID 23940314. Bibcode: 2013PNAS..11014132W.

- ↑ "Cytoplasmic streaming in plants". Current Opinion in Cell Biology 16 (1): 68–72. February 2004. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2003.11.009. PMID 15037307.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 5.21 5.22 "Microfluidics of cytoplasmic streaming and its implications for intracellular transport". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105 (10): 3663–7. March 2008. doi:10.1073/pnas.0707223105. PMID 18310326.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 "Cytoplasmic streaming velocity as a plant size determinant". Developmental Cell 27 (3): 345–52. November 2013. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2013.10.005. PMID 24229646.

- ↑ "Structure, function, and motility of vacuoles in filamentous fungi". Fungal Genetics and Biology 24 (1–2): 86–100. June 1998. doi:10.1006/fgbi.1998.1051. PMID 9742195.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 "Diffusive Promotion by Velocity Gradient of Cytoplasmic Streaming (CPS) in Nitella Internodal Cells". PLOS ONE 10 (12): e0144938. 2015. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0144938. PMID 26694322. Bibcode: 2015PLoSO..1044938K.

- ↑ Kamiya, Noburo; Kuroda, Kiyoko (1956). "Velocity Distribution of the Protoplasmic Streaming in Nitella Cells". Shokubutsugaku Zasshi 109 (822): 544–54. doi:10.15281/jplantres1887.69.544.

- ↑ The Principles of Engineering Materials. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. 1973. ISBN 978-0-137-09394-6.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "Effect of Cytoplasmic Streaming on Photosynthetic Activity of Chloroplasts in Internodes of Chara Corallina". Russian Journal of Plant Physiology 59: 35–41. 2011. doi:10.1134/S1021443711050050.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Staves, Mark P.; Wayne, Randy; Leopold, A. Carl (1997). "The Effect of the External Medium on the Gravity-Induced Polarity of Cytoplasmic Streaming in Chara Corallina (Characeae)". American Journal of Botany 84 (11): 1516–1521. doi:10.2307/2446612. PMID 11541058.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Calcium wave for cytoplasmic streaming of Physarum polycephalum". Cell Biology International 34 (1): 35–40. December 2009. doi:10.1042/CBI20090158. PMID 19947949.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.7 "Cellular Subcompartments through Cytoplasmic Streaming". Developmental Cell 34 (4): 410–20. August 2015. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2015.07.017. PMID 26305593.

- ↑ "How does a hypha grow? The biophysics of pressurized growth in fungi". Nature Reviews. Microbiology 9 (7): 509–18. June 2011. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2591. PMID 21643041. https://zenodo.org/record/941380.

- ↑ White, Frank (1986). Fluid Mechanics. New York, New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-070-69673-0.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 "Active diffusion positions the nucleus in mouse oocytes". Nature Cell Biology 17 (4): 470–9. April 2015. doi:10.1038/ncb3131. PMID 25774831. https://resolver.sub.uni-goettingen.de/purl?gro-2/68940.

Sources

- Riddle, D. L.; Blumenthal, T.; Meyer, B. J.; Priess, J. R. (1997). "Section III: Establishment of Polarity in the One-Cell Embryo". in Riddle, Donald L; Blumenthal, Thomas; Meyer, Barbara J et al.. C. elegans II (2nd ed.). Cold Spring Harbor (NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. ISBN 0-87969-532-3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK20089.

- Lodish, Harvey; Berk, Arnold; Zipursky, S Lawrence; Matsudaira, Paul; Baltimore, David; Darnell, James (2000). "Figure 18-40 Cytoplasmic streaming in cylindrical giant algae". Molecular Cell Biology (4th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-3136-3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK21562/figure/A5242.

- Lodish 2000, Section 18.5: Actin and Myosin in Nonmuscle Cells

External links

|