Biology:Penicillium solitum

| Penicillium solitum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Eurotiomycetes |

| Order: | Eurotiales |

| Family: | Aspergillaceae |

| Genus: | Penicillium |

| Species: | P. solitum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Penicillium solitum Westling, R. 1911[1]

| |

| Type strain | |

| ATCC 9923, Biourge 3, CBS 288.36, CBS 424.89, CCT 4377, FRR 0937, IBT 3948, IFO 7765, IMI 039810, IMI 092225, LSHB P52, MUCL 28668, MUCL 29173, NBRC 7765, NCTC 3029, NRRL 937, Thom 2546, Thom 4733.114, Thom, 2546, VKM F-3087[2] | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

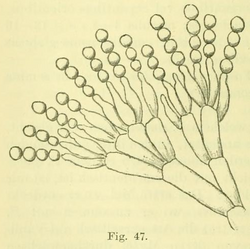

Penicillium solitum is an anamorphic, mesophilic, salinity-tolerant, and psychrotolerant species of fungus in the genus Penicillium. It is known to produce various compounds including polygalacturonase, compactin, cyclopenin, cyclopenol, cyclopeptin, dehydrocompactin, dihydrocyclopeptin, palitantin, solistatin, solistatinol, viridicatin, viridicatol.[1][3][4][5][6][7][8][9]

P. Solitum forms dark blueish-green colonies that measure 22–28 mm in diameter on Czaek yeast extract agar, while on malt extract agar, it appears brownish orange. This distinct orange-brown color sets P. solitum apart from other similar Penicillium species,[10] making it useful for differentiation. The fungus has been historically isolated from various sources, including cheese rinds,[11] cured meats,[12] and the Antarctic environment.[13] It was specifically isolated from air-dried lamb thighs on the Faore island.[8][failed verification] During the production of traditional Tyrolean smoked and cured ham, both Penicillium solitum and Eurotium rubrum are commonly found.[14]

Furthermore, Penicillium solitum is known to be a pathogen of pomaceous fruit,[15]P. solitum causes blue rot in pome fruits through its production of polygalacturonase, which breaks down the apple’s cell wall.[10]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Archived copy". https://www.mycobank.org/Biolomics.aspx?Table=Mycobank&MycoBankNr_=206172. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ↑ "Straininfo of Penicillium solitum". http://www.straininfo.net/taxa/10684;jsessionid=AD2BFD928A918E18BC1C3A128223E441.straininfo2.

- ↑ Sorensen, D; Ostenfeldlarsen, T; Christophersen, C; Nielsen, P; Anthoni, U (1999). "Solistatin, an aromatic compactin analogue from Penicillium solitum". Phytochemistry 51 (8): 1027. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(99)00015-1. Bibcode: 1999PChem..51.1027S.

- ↑ Larsen, Thomas Ostenfeld; Lange, Lene; Schnorr, Kirk; Stender, Steen; Frisvad, Jens Christian (2007). "Solistatinol, a novel phenolic compactin analogue from Penicillium solitum". Tetrahedron Letters 48 (7): 1261. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.12.038.

- ↑ "UniProt". https://www.uniprot.org/taxonomy/60172. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ↑ "ATCC: The Global Bioresource Center". https://www.atcc.org/. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- ↑ Gonçalves, Vívian N.; Campos, Lúcia S.; Melo, Itamar S.; Pellizari, Vivian H.; Rosa, Carlos A.; Rosa, Luiz H. (2013). "Penicillium solitum: A mesophilic, psychrotolerant fungus present in marine sediments from Antarctica". Polar Biology 36 (12): 1823. doi:10.1007/s00300-013-1403-8.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Jurick Wm, 2nd; Vico, I; Gaskins, V. L.; Whitaker, B. D.; Garrett, W. M.; Janisiewicz, W. J.; Conway, W. S. (2012). "Penicillium solitum produces a polygalacturonase isozyme in decayed Anjou pear fruit capable of macerating host tissue in vitro". Mycologia 104 (3): 604–12. doi:10.3852/11-119. PMID 22241612.

- ↑ Carl A. Batt (2014). Encyclopedia of Food Microbiology. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0123847331.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Pitt, J. I. (1991). "Penicillium solitum Revived, and its Role as a Pathogen of Pomaceous Fruit". Phytopathology 81 (10): 1108. doi:10.1094/Phyto-81-1108. http://www.apsnet.org/publications/phytopathology/backissues/Documents/1991Abstracts/Phyto81_1108.htm. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ↑ Decontardi, S.; Mauro, A.; Lima, N.; Battilani, P. (4 April 2017). "Survey of Penicillia associated with Italian grana cheese". International Journal of Food Microbiology 246: 25–31. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2017.01.019. ISSN 1879-3460. PMID 28187328. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28187328/. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- ↑ Núñez, Félix; Westphal, Carmen D.; Bermúdez, Elena; Asensio, Miguel A. (December 2007). "Production of secondary metabolites by some terverticillate penicillia on carbohydrate-rich and meat substrates". Journal of Food Protection 70 (12): 2829–2836. doi:10.4315/0362-028x-70.12.2829. ISSN 0362-028X. PMID 18095438.

- ↑ Gonçalves, Vívian N.; Campos, Lúcia S.; Melo, Itamar S.; Pellizari, Vivian H.; Rosa, Carlos A.; Rosa, Luiz H. (1 December 2013). "Penicillium solitum: a mesophilic, psychrotolerant fungus present in marine sediments from Antarctica" (in en). Polar Biology 36 (12): 1823–1831. doi:10.1007/s00300-013-1403-8. ISSN 1432-2056. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-013-1403-8.

- ↑ Y. H. Hui; Lisbeth Meunier-Goddik; Jytte Josephsen; Wai-Kit Nip; Peggy S. Stanfield (2004). Handbook of Food and Beverage Fermentation Technology. SCRC Press. ISBN 0203913558.

- ↑ Clive de W Blackburn (2006). Food Spoilage Microorganisms. Woodhead Publishing. ISBN 1845691415.

Further reading

- Gonçalves, Vívian N.; Campos, Lúcia S.; Melo, Itamar S.; Pellizari, Vivian H.; Rosa, Carlos A.; Rosa, Luiz H. (2013). "Penicillium solitum: A mesophilic, psychrotolerant fungus present in marine sediments from Antarctica". Polar Biology 36 (12): 1823. doi:10.1007/s00300-013-1403-8.

- Eldarov, Michael A.; Mardanov, Andrey V.; Beletsky, Alexey V.; Dzhavakhiya, Vakhtang V.; Ravin, Nikolai V.; Skryabin, Konstantin G. (2012). "Complete mitochondrial genome of compactin-producing fungus Penicillium solitum and comparative analysis of Trichocomaceae mitochondrial genomes". FEMS Microbiology Letters 329 (1): 9–17. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02497.x. PMID 22239643.

- Pitt, J. I. (1991). "Penicillium solitum Revived, and its Role as a Pathogen of Pomaceous Fruit". Phytopathology 81 (10): 1108. doi:10.1094/Phyto-81-1108.

- Chinaglia, Selene; Chiarelli, Laurent R.; Maggi, Maristella; Rodolfi, Marinella; Valentini, Giovanna; Picco, Anna Maria (2014). "Biochemistry of lipolytic enzymes secreted by Penicillium solitumand Cladosporium cladosporioides". Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 78 (2): 245–254. doi:10.1080/09168451.2014.882752. PMID 25036677.

- Stierle, Donald B.; Stierle, Andrea A.; Girtsman, Teri; McIntyre, Kyle; Nichols, Jesse (2012). "Caspase-1 and -3 Inhibiting Drimane Sesquiterpenoids from the Extremophilic Fungus Penicillium solitum". Journal of Natural Products 75 (2): 262–266. doi:10.1021/np200528n. PMID 22276851.

- Sorensen, D; Ostenfeldlarsen, T; Christophersen, C; Nielsen, P; Anthoni, U (1999). "Solistatin, an aromatic compactin analogue from Penicillium solitum". Phytochemistry 51 (8): 1027. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(99)00015-1. Bibcode: 1999PChem..51.1027S.

- Romanovskaya, I. I.; Bondarenko, G. I.; Davidenko, T. I. (2008). "Immobilization of Penicillium solitum lipase on the carbon fiber material "Dnepr-MN"". Pharmaceutical Chemistry Journal 42 (6): 360. doi:10.1007/s11094-008-0127-5.

- Yan, Mengxia; Mao, Wenjun; Chen, Chenglong; Kong, Xianglan; Gu, Qianqun; Li, Na; Liu, Xue; Wang, Baofeng et al. (2014). "Structural elucidation of the exopolysaccharide produced by the mangrove fungus Penicillium solitum". Carbohydrate Polymers 111: 485–91. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.05.013. PMID 25037379.

- Jurick, W. M.; Vico, I; McEvoy, J. L.; Whitaker, B. D.; Janisiewicz, W; Conway, W. S. (2009). "Isolation, purification, and characterization of a polygalacturonase produced in Penicillium solitum-decayed 'Golden Delicious' apple fruit". Phytopathology 99 (6): 636–41. doi:10.1094/PHYTO-99-6-0636. PMID 19453221. https://naldc-legacy.nal.usda.gov/naldc/download.xhtml?id=31693&content=PDF.

- John I. Pitt; A.D. Hocking (2012). Fungi and Food Spoilage. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1461563914.

- Atta-ur- Rahman (2013). Studies in Natural Products Chemistry volume 39. Newnes. ISBN 978-0444626097.

Wikidata ☰ Q15020954 entry

|