Biology:Seaweed

| Biology:Seaweed Informal group of macroscopic marine algae

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Fucus serratus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Seaweeds can be found in the following groups | |

| |

Seaweed, or macroalgae, refers to thousands of species of macroscopic, multicellular, marine algae. The term includes some types of Rhodophyta (red), Phaeophyta (brown) and Chlorophyta (green) macroalgae. Seaweed species such as kelps provide essential nursery habitat for fisheries and other marine species and thus protect food sources; other species, such as planktonic algae, play a vital role in capturing carbon, producing at least 50% of Earth's oxygen.[3]

Natural seaweed ecosystems are sometimes under threat from human activity. For example, mechanical dredging of kelp destroys the resource and dependent fisheries. Other forces also threaten some seaweed ecosystems; a wasting disease in predators of purple urchins has led to an urchin population surge which destroyed large kelp forest regions off the coast of California.[4]

Humans have a long history of cultivating seaweeds for their uses. In recent years, seaweed farming has become a global agricultural practice, providing food, source material for various chemical uses (such as carrageenan), cattle feeds and fertilizers. Because of their importance in marine ecologies and for absorbing carbon dioxide, recent attention has been on cultivating seaweeds as a potential climate change mitigation strategy for biosequestration of carbon dioxide, alongside other benefits like nutrient pollution reduction, increased habitat for coastal aquatic species, and reducing local ocean acidification.[5] The IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate recommends "further research attention" as a mitigation tactic.[6]

Taxonomy

"Seaweed" lacks a formal definition, but seaweed generally lives in the ocean and is visible to the naked eye. The term refers to both flowering plants submerged in the ocean, like eelgrass, as well as larger marine algae. Generally, it is one of several groups of multicellular algae: red, green and brown. They lack one common multicellular ancestor, forming a polyphyletic group. In addition, bluegreen algae (Cyanobacteria) are occasionally considered in seaweed literature.[7]

The number of seaweed species is still discussed among scientists, but most likely there are several thousand species of seaweed.[8]

Genera

The following table lists a very few example genera of seaweed.

| Genus | Algae Phylum |

Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caulerpa |  |

Green | Submerged |

| Fucus |  |

Brown | In intertidal zones on rocky shores |

| Gracilaria |  |

Red | Cultivated for food |

| Laminaria |  |

Brown | Also known as kelp 8–30 m under water cultivated for food |

| Macrocystis |  |

Brown | Giant kelp forming floating canopies |

| Monostroma |  |

Green | |

| Porphyra |  |

Red | Intertidal zones in temperate climate Cultivated for food |

| Sargassum |  |

Brown | Pelagic especially in the Sargasso Sea |

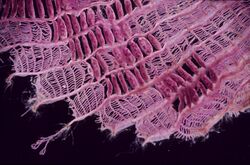

Anatomy

Seaweed's appearance resembles non-woody terrestrial plants. Its anatomy includes:[9][10]

- Thallus: algal body

- Lamina or blade: flattened structure that is somewhat leaf-like

- Sorus: spore cluster

- pneumatocyst, air bladder: a flotation-assisting organ on the blade

- Kelp, float: a flotation-assisting organ between the lamina and stipe

- Stipe: stem-like structure, may be absent

- Holdfast: basal structure providing attachment to a substrate

- Haptera: finger-like extension of the holdfast that anchors to a benthic substrate

- Lamina or blade: flattened structure that is somewhat leaf-like

The stipe and blade are collectively known as the frond.

Ecology

Two environmental requirements dominate seaweed ecology. These are seawater (or at least brackish water) and light sufficient to support photosynthesis. Another common requirement is an attachment point, and therefore seaweed most commonly inhabits the littoral zone (nearshore waters) and within that zone, on rocky shores more than on sand or shingle. In addition, there are few genera (e.g., Sargassum and Gracilaria) which do not live attached to the sea floor, but float freely.

Seaweed occupies various ecological niches. At the surface, they are only wetted by the tops of sea spray, while some species may attach to a substrate several meters deep. In some areas, littoral seaweed colonies can extend miles out to sea.[citation needed] The deepest living seaweed are some species of red algae. Others have adapted to live in tidal rock pools. In this habitat, seaweed must withstand rapidly changing temperature and salinity and occasional drying.[11]

Macroalgae and macroalgal detritus have also been shown to be an important food source for benthic organisms, because macroalgae shed old fronds.[12] These macroalgal fronds tend to be utilized by benthos in the intertidal zone close to the shore.[13][14] Alternatively, pneumatocysts (gas filled "bubbles") can keep the macroalgae thallus afloat fronds are transported by wind and currents from the coast into the deep ocean.[12] It has been shown that benthic organisms also at several 100 m tend to utilize these macroalgae remnants.[14]

As macroalgae takes up carbon dioxide and release oxygen in the photosynthesis, macroalgae fronds can also contribute to carbon sequestration in the ocean, when the macroalgal fronds drift offshore into the deep ocean basins and sink to the sea floor without being remineralized by organisms.[12] The importance of this process for the Blue Carbon storage is currently discussed among scientists.[15][16][17]

Biogeographic expansion

Nowadays a number of vectors - e.g., transport on ship hulls, exchanges among shellfish farmers, global warming, opening of trans-oceanic canals - all combine to enhance the transfer of exotic seaweeds to new environments. Since the piercing of the Suez Canal,the situation is particularly acute in the Mediterranean Sea, a 'marine biodiversity hotspot' that now registers over 120 newly introduced seaweed species -the largest number in the world.[18]

Production

As of 2019, 35,818,961 tonnes were produced, of which 97.38% were produced in Asian countries.[19]

| Country | tonns per year, cultured and wild |

|---|---|

| China | 20,351,442 |

| Indonesia | 9,962,900 |

| South Korea | 1,821,475 |

| Philippines | 1,500,326 |

| North Korea | 603,000 |

| Chile | 427,508 |

| Japan | 412,300 |

| Malaysia | 188,110 |

| Norway | 163,197 |

| United Republic of Tanzania | 106,069 |

Farming

Uses

Seaweed has a variety of uses, for which it is farmed[20] or foraged.[21]

Food

Seaweed is consumed across the world, particularly in East Asia, e.g. Japan , China , Korea, Taiwan and Southeast Asia, e.g. Brunei, Singapore, Thailand, Burma, Cambodia, Vietnam, Indonesia, the Philippines , and Malaysia,[22] as well as in South Africa , Belize, Peru, Chile , the Canadian Maritimes, Scandinavia, South West England,[23] Ireland, Wales, Hawaii and California , and Scotland.

Gim (김, Korea), nori (海苔, Japan) and zicai (紫菜, China) are sheets of dried Porphyra used in soups, sushi or onigiri (rice balls). Gamet in the Philippines, from dried Pyropia, is also used as a flavoring ingredient for soups, salads and omelettes.[24] Chondrus crispus ('Irish moss' or carrageenan moss) is used in food additives, along with Kappaphycus and Gigartinoid seaweed. Porphyra is used in Wales to make laverbread (sometimes with oat flour). In northern Belize, seaweed is mixed with milk, nutmeg, cinnamon and vanilla to make "dulce" ("sweet").

Alginate, agar and carrageenan are gelatinous seaweed products collectively known as hydrocolloids or phycocolloids. Hydrocolloids are food additives.[25] The food industry exploits their gelling, water-retention, emulsifying and other physical properties. Agar is used in foods such as confectionery, meat and poultry products, desserts and beverages and moulded foods. Carrageenan is used in salad dressings and sauces, dietetic foods, and as a preservative in meat and fish, dairy items and baked goods.

Medicine and herbs

Alginates are used in wound dressings (see alginate dressing), and dental moulds. In microbiology, agar is used as a culture medium. Carrageenans, alginates and agaroses, with other macroalgal polysaccharides, have biomedicine applications. Delisea pulchra may interfere with bacterial colonization.[26] Sulfated saccharides from red and green algae inhibit some DNA and RNA-enveloped viruses.[27]

Seaweed extract is used in some diet pills.[28] Other seaweed pills exploit the same effect as gastric banding, expanding in the stomach to make the stomach feel more full.[29][30]

Climate change mitigation

Other uses

Other seaweed may be used as fertilizer, compost for landscaping, or to combat beach erosion through burial in beach dunes.[31]

Seaweed is under consideration as a potential source of bioethanol.[32][33]

Alginates are used in industrial products such as paper coatings, adhesives, dyes, gels, explosives and in processes such as paper sizing, textile printing, hydro-mulching and drilling. Seaweed is an ingredient in toothpaste, cosmetics and paints. Seaweed is used for the production of bio yarn (a textile).[34]

Several of these resources can be obtained from seaweed through biorefining.

Seaweed collecting is the process of collecting, drying and pressing seaweed. It was a popular pastime in the Victorian era and remains a hobby today. In some emerging countries, Seaweed is harvested daily to support communities.

Seaweed is sometimes used to build roofs on houses on Læsø in Denmark [35]

Seaweeds are used as animal feeds. They have long been grazed by sheep, horses and cattle in Northern Europe. They are valued for fish production.[36] Adding seaweed to livestock feed can substantially reduce methane emissions from cattle,[37] but only from their feedlot emissions. As of 2021, feedlot emissions account for 11% of overall emissions from cattle. [38]

Onigiri and wakame miso soup, Japan

Laverbread and toast

Health risks

Rotting seaweed is a potent source of hydrogen sulfide, a highly toxic gas, and has been implicated in some incidents of apparent hydrogen-sulphide poisoning.[39] It can cause vomiting and diarrhea.

The so-called "stinging seaweed" Microcoleus lyngbyaceus is a filamentous cyanobacteria which contains toxins including lyngbyatoxin-a and debromoaplysiatoxin. Direct skin contact can cause seaweed dermatitis characterized by painful, burning lesions that last for days.[1][40]

Threats

Bacterial disease ice-ice infects Kappaphycus (red seaweed), turning its branches white. The disease caused heavy crop losses in the Philippines, Tanzania and Mozambique.[41]

Sea urchin barrens have replaced kelp forests in multiple areas. They are "almost immune to starvation". Lifespans can exceed 50 years. When stressed by hunger, their jaws and teeth enlarge, and they form "fronts" and hunt for food collectively.[41]

See also

- Biology:Algaculture – Aquaculture involving the farming of algae

- Seaweed fertilizer

- Biology:Algae fuel – Use of algae as a source of energy-rich oils

- Cochayuyo – Species of seaweed, a form of kelp used as a vegetable in Chile

- Biology:Hijiki – Species of seaweed

- Biology:Kombu – Edible kelp

- Limu

- Mozuku – Species of seaweed

- Biology:Nori – Edible seaweed species of the red algae genus Pyropia

- Ogonori – Genus of seaweeds

- Biology:Wakame – Species of seaweed

- Marine permaculture

- Biology:Sea lettuce – Genus of seaweeds

- Biology:Seaweed cultivator

- Seaweed dermatitis – Species of bacterium

- Seaweed toxins

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Escharotic stomatitis caused by the "stinging seaweed" Microcoleus lyngbyaceus (formerly Lyngbya majuscula): case report and literature review". https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/19822902103.

- ↑ James, William D. et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6.

- ↑ "How much oxygen comes from the ocean?". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/ocean-oxygen.html.

- ↑ "California's crashing kelp forest" (in en). https://phys.org/news/2019-10-california-kelp-forest.html.

- ↑ Duarte, Carlos M.; Wu, Jiaping; Xiao, Xi; Bruhn, Annette; Krause-Jensen, Dorte (2017). "Can Seaweed Farming Play a Role in Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation?" (in en). Frontiers in Marine Science 4. doi:10.3389/fmars.2017.00100. ISSN 2296-7745.

- ↑ Bindoff, N. L.; Cheung, W. W. L.; Kairo, J. G.; Arístegui, J. et al. (2019). "Chapter 5: Changing Ocean, Marine Ecosystems, and Dependent Communities". IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. pp. 447–587. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/sites/3/2019/11/09_SROCC_Ch05_FINAL.pdf.

- ↑ Lobban, Christopher S.; Harrison, Paul J. (1994). "Morphology, life histories, and morphogenesis". Seaweed Ecology and Physiology: 1–68. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511626210.002. ISBN 9780521408974. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/seaweed-ecology-and-physiology/morphology-life-histories-and-morphogenesis/9359C9B0571E8E75645CBA3C10D9AD58.

- ↑ Townsend, David W. (March 2012). Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Introduction to Marine Science. Oxford University Press Inc. ISBN 9780878936021.

- ↑ "seaweed menu". https://www.easterncapescubadiving.co.za/index.php?page_name=more&list_id=158.

- ↑ "The Science of Seaweeds" (in en). 2017-02-06. https://www.americanscientist.org/article/the-science-of-seaweeds.

- ↑ Lewis, J. R. 1964. The Ecology of Rocky Shores. The English Universities Press Ltd.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Krause-Jensen, Dorte; Duarte, Carlos (2016). "Substantial role of macroalgae in marine carbon sequestration". Nature Geoscience 9 (10): 737–742. doi:10.1038/ngeo2790. Bibcode: 2016NatGe...9..737K. https://www.nature.com/articles/ngeo2790#citeas..

- ↑ Dunton, K. H.; Schell, D. M. (1987). "Dependence of consumers on macroalgal (Laminaria solidungula) carbon in an arctic kelp community: δ13C evidence". Marine Biology 93 (4): 615–625. doi:10.1007/BF00392799. Bibcode: 1987MarBi..93..615D.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Renaud, Paul E.; Løkken, Therese S.; Jørgensen, Lis L.; Berge, Jørgen; Johnson, Beverly J. (June 2015). "Macroalgal detritus and food-web subsidies along an Arctic fjord depth-gradient". Front. Mar. Sci. 2. doi:10.3389/fmars.2015.00031.

- ↑ Watanabe, Kenta; Yoshida, Goro; Hori, Masakazu; Umezawa, Yu; Moki, Hirotada; Kuwae, Tomohiro (May 2020). "Macroalgal metabolism and lateral carbon flows can create significant carbon sinks". Biogeosciences 17 (9): 2425–2440. doi:10.5194/bg-17-2425-2020. Bibcode: 2020BGeo...17.2425W. https://bg.copernicus.org/articles/17/2425/2020/. Retrieved September 21, 2020.

- ↑ Krause-Jensen, Dorte; Lavery, Paul; Serrano, Oscar; Marbà, Núria; Masque, Pere; Duarte, Carlos M. (June 2018). "Sequestration of macroalgal carbon: the elephant in the Blue Carbon room". The Royal Society Publishing 14 (6). doi:10.1098/rsbl.2018.0236. PMID 29925564.

- ↑ Ortega, Alejandra; Geraldi, Nathan R.; Alam, Intikhab; Kamau, Allan A.; Acinas, Silvia G; Logares, Ramiro; Gasol, Josep M; Massana, Ramon et al. (2019). "Important contribution of macroalgae to oceanic carbon sequestration". Nature Geoscience 12 (9): 748–754. doi:10.1038/s41561-019-0421-8. Bibcode: 2019NatGe..12..748O.

- ↑ Briand, Frederic, ed (2015). CIESM Atlas of Exotic Species in the Mediterranean. Volume 4. Macrophytes.. CIESM, Paris, Monaco. pp. 364. ISBN 9789299000342. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/299381362.

- ↑ Global seaweeds and microalgae production(FAO)

- ↑ "Seaweed farmers get better prices if united". Sun.Star. 2008-06-19. http://www.sunstar.com.ph/static/dav/2008/06/19/bus/seaweed.farmers.get.better.prices.if.united.jica.html.

- ↑ "Springtime's foraging treats". The Guardian (London). 2007-01-06. http://lifeandhealth.guardian.co.uk/guides/freestuff/story/0,,1981372,00.html.

- ↑ Mohammad, Salma (4 Jan 2020). "Application of seaweed (Kappaphycus alvarezii) in Malaysian food products". International Food Research Journal 26: 1677–1687. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338254486.

- ↑ "Devon Family Friendly – Tasty Seaweed Recipe – Honest!". BBC. 2005-05-25. https://www.bbc.co.uk/devon/discovering/taste/laver.shtml.

- ↑ Adriano, Leilanie G. (21 December 2005). "'Gamet' sushi festival launched". The Manila Times. https://www.manilatimes.net/2005/12/21/news/regions/gamet-sushi-festival-launched/693918.

- ↑ Round F. E. 1962 The Biology of the Algae. Edward Arnold Ltd.

- ↑ Francesca Cappitelli; Claudia Sorlini (2008). "Microorganisms attack synthetic polymers in items representing our cultural heritage". Applied and Environmental Microbiology 74 (3): 564–569. doi:10.1128/AEM.01768-07. PMID 18065627. Bibcode: 2008ApEnM..74..564C.

- ↑ Kazłowski B.; Chiu Y. H.; Kazłowska K.; Pan C. L.; Wu C. J. (August 2012). "Prevention of Japanese encephalitis virus infections by low-degree-polymerisation sulfated saccharides from Gracilaria sp. and Monostroma nitidum". Food Chem. 133 (3): 866–74. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.01.106.

- ↑ Maeda, Hayato; Hosokawa, Masashi; Sashima, Tokutake; Funayama, Katsura; Miyashita, Kazuo (2005-07-01). "Fucoxanthin from edible seaweed, Undaria pinnatifida, shows antiobesity effect through UCP1 expression in white adipose tissues". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 332 (2): 392–397. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.002. ISSN 0006-291X. PMID 15896707.

- ↑ "New Seaweed Pill Works Like Gastric Banding". 25 March 2015. https://www.foxnews.com/story/new-seaweed-pill-works-like-gastric-banding.

- ↑ Elena Gorgan (6 January 2009). "Appesat, the Seaweed Diet Pill that Expands in the Stomach". http://news.softpedia.com/news/Appesat-the-Seaweed-Diet-Pill-that-Expands-in-the-Stomach-101227.shtml.

- ↑ Rodriguez, Ihosvani (April 11, 2012). "Seaweed invading South Florida beaches in large numbers". South Florida Sun-Sentinel. http://www.sun-sentinel.com/news/broward/fort-lauderdale/fl-lauderdale-beach-seaweed-20120410,0,3244366.story.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ "Seaweed Power: Ireland Taps New Energy Source". 2008-06-24. http://alotofyada.blogspot.co.uk/2008/06/seaweed-power-ireland-taps-new-energy.html.

- ↑ Chen, Huihui; Zhou, Dong; Luo, Gang; Zhang, Shicheng; Chen, Jianmin (2015). "Macroalgae for biofuels production: Progress and perspectives". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 47: 427–437. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2015.03.086.

- ↑ "The promise of Bioyarn from AlgiKnit". https://www.materialdriven.com/home/2017/6/16/the-promise-of-bioyarn-from-algiknit.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ "Seaweed Thatch". http://naturalhomes.org/seaweed-house.htm.

- ↑ Heuzé V., Tran G., Giger-Reverdin S., Lessire M., Lebas F., 2017. Seaweeds (marine macroalgae). Feedipedia, a programme by INRA, CIRAD, AFZ and FAO. https://www.feedipedia.org/node/78 Last updated on May 29, 2017, 16:46

- ↑ "Seaweed shown to reduce 99% methane from cattle". https://www.irishtimes.com/news/ireland/irish-news/seaweed-shown-to-reduce-99-methane-from-cattle-1.3156975.

- ↑ Dutkiewicz, Jan. "Want Carbon-Neutral Cows? Algae Isn't the Answer" (in en-US). Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. https://www.wired.com/story/carbon-neutral-cows-algae/. Retrieved 2023-12-30.

- ↑ "Algues vertes: la famille du chauffeur décédé porte plainte contre X" (in fr). Saint-Brieuc: AFP. 2010-04-22. http://www.google.com/hostednews/afp/article/ALeqM5hmSXIrejkYYs-g9Y0L71SD9qNl7w?hl=fr.

- ↑ Werner, K. A.; Marquart, L.; Norton, S. A. (2012). "Lyngbya dermatitis (toxic seaweed dermatitis)". International Journal of Dermatology 51 (1): 59–62. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05042.x. PMID 21790555.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Buck, Holly Jean (April 23, 2019). "The desperate race to cool the ocean before it's too late" (in en-US). https://www.technologyreview.com/s/613327/the-desperate-race-to-cool-the-ocean-before-its-too-late/.

Further reading

- Christian Wiencke, Kai Bischof (ed.)(2012). Seaweed Biology: Novel Insights into Ecophysiology, Ecology & Utilization. Springer. ISBN:978-3-642-28450-2 (print); ISBN:978-3-642-28451-9 (eBook).

External links

- Michael Guiry's Seaweed Site information on all aspects of algae, seaweed and marine algal biology

- SeaweedAfrica, information on seaweed utilisation for the African continent.

- Seaweed. A chemical industry in Brittany, in the past and today.

- AlgaeBase, a searchable taxonomic, image, and utilization database of freshwater, marine and terrestrial algae, including seaweed.

|