Biology:Rufous woodpecker

| Rufous woodpecker | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male rufous woodpecker in the Western Ghats | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Piciformes |

| Family: | Picidae |

| Genus: | Micropternus Blyth, 1845 |

| Species: | M. brachyurus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Micropternus brachyurus (Vieillot, 1818)

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The rufous woodpecker (Micropternus brachyurus) is a medium-sized brown woodpecker native to South and Southeast Asia. It is short-billed, foraging in pairs on small insects, particularly ants and termites, in scrub, evergreen, and deciduous forests and is noted for building its nest within the carton nests of arboreal ants in the genus Crematogaster. It was for sometime placed in the otherwise Neotropical genus Celeus but this has been shown to be a case of evolutionary convergence and molecular phylogenetic studies support its placement in the monotypic genus Micropternus.

Taxonomy

This species was formerly placed in the South American genus Celeus due to external resemblance but its disjunct distribution placed it in doubt. Studied in 2006 based on DNA sequence comparisons have confirmed that the rufous woodpecker is not closely related to Celeus and is a sister of the genus Meiglyptes and best placed within the monotypic genus Micropternus.[1] The genus Micropternus was erected by Edward Blyth who separated it from Meiglyptes based on the short first toe with reduced claw. Other genus characters are the short bill lacking a nasal ridge. The nostrils are round and the outer tail feathers are short and about as long as the tail-coverts.[2][3]

Within the wide distribution range of the species, several plumage and size differences are noted among the populations which have been designed as subspecies of which about ten are widely recognized with the nominate population being from Java.[4][5][6]

- M. b. brachyurus (Vieillot, 1818) – Java.

- M. b. humei Kloss, 1918 – along the western Himalayas has a streaked throat, greyish head and a pale face.

- M. b. jerdonii (Malherbe, 1849)[7] [includes kanarae from the northern western ghats noted as larger by Koelz[8]] – peninsular India and Sri Lanka

- M. b. phaioceps (Blyth, 1845) – eastern Himalayas from central Nepal to Myanmar, Yunnan and southern Thailand.

- M. b. fokiensis (Swinhoe, 1863) – (has a sooty abdomen) southeast China and northern Vietnam.

- M. b. holroydi Swinhoe, 1870 – Hainan.

- M. b. williamsoni Kloss, 1918 – southern Thailand. Sometimes included within badius

- M. b. annamensis Delacour & Jabouille, 1924 – Laos, Cambodia and southern Vietnam.

- M. b. badius (Raffles, 1822) – [includes celaenephis of Nias Island] Malay Peninsula south to Sumatra

- M. b. badiosus (Bonaparte, 1850) – (has a very dark tail) Borneo and north Natuna Islands

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Relationship to other genera.[1][9][10] |

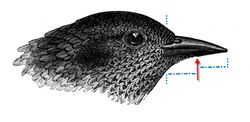

Description

The rufous woodpecker is about 25 cm long, overall dark brown with dark bands on the feathers of the wing and tail giving it a black-barred appearance. The head appears paler and underparts are of a darker shade. The bill is short and black with a slight curvature of the culmen. At the nostrils the bill is narrow. The tail is short and rufous with narrow black bars but in subspecies badiosus the tail is dark with narrow rufous bars. Feather margins are pale in squamigularis and annamensis. Feathers on the neck, ears and lore are unmarked. Males have red-tipped feathers under eyes, between eye and ear coverts and on malar region sometimes forming a patch. Females and young lack the red feather tips. A weak but erectile crest is present. Juveniles appear streaked on the throat but some subspecies also have streaked throat feathers. In the field, birds can appear soiled and smell of ant secretions (Crematogaster ants are unique in having a spatulate tip to the sting that is used merely to spray fluid forward at intruders from a raised gaster[11]) due to their foraging or nesting activities.[6][12]

Behaviour and ecology

Rufous woodpeckers forage in pairs on ant nests on trees, fallen logs, dung heaps, ant, and termite hills. They have been noted to feed on ants of the genera Crematogaster and Oecophylla.[13] Apart from insects, it has been seen taking nectar from flowers of Bombax and Erythrina and taking sap from the bases of banana fronds. The most common call is a sharp nasal, three-note, keenk-keenk-keenk but they have other calls including a long wicka and a series of wick-wick notes. They also have a distinctive drumming note which starts rapidly and then slows down in tempo.[14] Drumming occurs through the year but increases in frequency in winter in southern India[15] and peaking around March–April in Nepal.[16] A display of unknown function between two birds facing each other involved swaying the head with bill held high and tail splayed.[13] The breeding season is in the pre-Monsoon dry period from February to June. The rufous woodpecker is most well known for building its nest within the nest of acrobat ants (Crematogaster).[17][18] Both the male and female take part in the excavation of the nest. Their feathers, particularly when nesting are said to be covered in a dark and smelly sticky fluid on which dead ants are often found sticking. Two white, matt, thin-shelled, translucent eggs are laid. The incubation period is 12 to 14 days.[6] Both parents feed the young at nest although a 19th-century observer reported that his Indian field assistants who called the bird "lal sutar", meaning red carpenter, believed that the adults left the young to obtain ants to feed themselves.[19] The moult occurs mainly from September to November.[6] Bird lice of the species Penenirmus auritus have been recorded from this species in Thailand.[20] The species has a wide habitat range and in Malaysia they have been found to persist even in places where swamp forests have been removed and replaced by oil palm plantations.[21] Their habitat is mainly in the plains and lower hills mostly below 3000 m.[22] This bird is not considered threatened on the IUCN Red List.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Benz, B.W.; Robbins, M.B.; Peterson, A.T. (2006). "Evolutionary history of woodpeckers and allies (Aves: Picidae): Placing key taxa on the phylogenetic tree". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 40 (2): 389–399. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.02.021. PMID 16635580. http://darwin.biology.utah.edu/China/PDFs/TaxaBirds4.pdf.

- ↑ Blyth, Edward (1845). "Notices and descriptions of various new or little known species of birds". Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 14: 173–212. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/40131965.

- ↑ Ali, Salim; Ripley, S. Dillon (1983). Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan. Volume 4. (2 ed.). Delhi: Oxford University Press. pp. 171–181.

- ↑ Robinson, H.C. (1919). "Note on certain recently described subspecies of woodpeckers". Ibis. 11 1 (2): 179–181. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/16342418.

- ↑ Peters, James Lee (1948). Check-list of birds of the world. Volume VI.. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 128–129. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/14477561.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Short, Lester L. (1982). Woodpeckers of the World. Delaware Museum of Natural History. pp. 390–393. https://archive.org/details/woodpeckersofwor00unse.

- ↑ Malherbe, Alfred (1849). "Description de quelques nouvelles especes de Picines (Picus, Linn.)". Revue et magasin de zoologie pure et appliquée: 529–544. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/2343765.

- ↑ Koelz, W (1950). "New subspecies of birds from southwestern Asia.". Am. Mus. Novit. 1452: 1–10.

- ↑ Fuchs, J.; Pons, J.-M.; Ericson, P.G.P.; Bonillo, C.; Couloux, A.; Pasquet, E. (2008). "Molecular support for a rapid cladogenesis of the woodpecker clade Malarpicini, with further insights into the genus Picus (Piciformes: Picinae)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 48 (1): 34–46. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2008.03.036. PMID 18487062.

- ↑ Zhou, C.; Hao, Y.; Ma, J.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Y.; Chen, B.; Zhang, X.; Yue, B. (2017). "The first complete mitogenome of Picumnus innominatus (Aves, Piciformes, Picidae) and phylogenetic inference within the Picidae". Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 70: 274–282. doi:10.1016/j.bse.2016.12.003.

- ↑ Buren, William F. (1958). "A Review of the Species of Crematogaster, Sensu Stricto, in North America (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Part I". Journal of the New York Entomological Society 66 (3/4): 119–134.

- ↑ Blanford, W.T. (1895). The Fauna of British India including Ceylon and Burma. Birds. Volume III.. London: Taylor and Francis. pp. 54–58. https://archive.org/details/birdsindia03oaterich.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Santharam, V. (1997). "Display behaviour in Woodpeckers". Newsletter for Birdwatchers 37 (6): 98–99. https://archive.org/details/NLBW37_6/page/n8.

- ↑ Short, L.L. (1973). "Habits of some Asian woodpeckers (Aves, Picidae)". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 152 (5): 281–283.

- ↑ Santharam, V. (1998). "Drumming frequency in Woodpeckers". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 95 (3): 506–507. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/48605056.

- ↑ Proud, Desiree (1958). "Woodpeckers drumming". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 55: 350–351. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/48068857.

- ↑ Moreau, R.E. (1936). "Bird-Insect Nesting Associations". Ibis 78 (3): 460–471. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1936.tb03399.x.

- ↑ Betts, F.N. (1934). "South Indian Woodpeckers". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 37 (1): 197–203. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/48185475.

- ↑ Wilson, N.F.T. (1898). "The nesting of the Malabar Rufous Woodpecker Micropternus gularis". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 11 (4): 744–745. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/30157529.

- ↑ Dalgleish, R.C. (1972). "The Penenirmus (Mallophaga: Ischnocera) of the Picidae (Aves: Piciformes)". Journal of the New York Entomological Society 80 (2): 83–104.

- ↑ Hawa, A.; Azhar, B.; Top, M.M.; Zubaid, A. (2016). "Depauperate Avifauna in Tropical Peat Swamp Forests Following Logging and Conversion to Oil Palm Agriculture: Evidence from Mist-netting Data". Wetlands 36 (5): 899–908. doi:10.1007/s13157-016-0802-3. http://psasir.upm.edu.my/id/eprint/55439/1/Depauperate%20avifauna%20in%20tropical%20peat%20swamp%20forests%20following%20logging%20and%20conversion%20.pdf.

- ↑ Rasmussen, P.C.; Anderton, J.C. (2005). Birds of South Asia. The Ripley Guide. Volume 2. Smithsonian Institution and Lynx Edicions. p. 285.

Wikidata ☰ Q1274095 entry

|