Biology:Haplogroup DE

| Haplogroup DE | |

|---|---|

| Possible time of origin | 68,500 years BP,[1] 68,555 years BP,[2] 70,000 years BP,[3] 76,500 years BP[4] |

| Coalescence age | 65,200-76,500 years BP[1][4] |

| Possible place of origin | Africa[5][4] or Eurasia[6] |

| Ancestor | CT |

| Descendants | E, D |

| Defining mutations | M1/YAP, M145 = P205, M203, P144, P153, P165, P167, P183 |

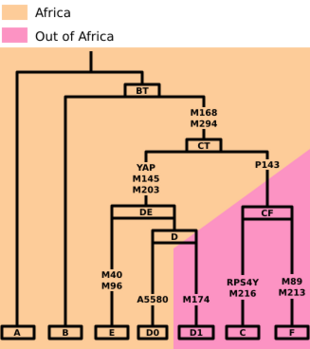

Haplogroup DE is a human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup. It is defined by the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) mutations, or UEPs, M1(YAP), M145(P205), M203, P144, P153, P165, P167, P183.[7] DE is unique because it is distributed in several geographically distinct clusters. An immediate subclade, haplogroup D (also known as D-CTS3946), is mainly found in East Asia, parts of Central Asia, and the Andaman Islands, but also sporadically in West Africa and West Asia. The other immediate subclade, haplogroup E, is common in Africa, and to a lesser extent the Middle East and southern Europe.

The most well-known unique event polymorphism (UEP) that defines DE is the Y-chromosome Alu Polymorphism "YAP". The mutation was caused when a strand of DNA, known as Alu, inserted a copy of itself into the Y chromosome. Hence, all Y chromosomes belonging to DE, D, E and their subclades are YAP-positive (YAP+). All Y chromosomes that belong to other haplogroups and subclades are YAP-negative (YAP-).

The age of haplogroup DE, previously estimated at between 65,000 and 71,000 years,[8] was later estimated at around 68,555 years [2] and most recently at around 76,500 years old.[4]

Origins

Discovery

The YAP insertion was discovered by scientists led by Michael Hammer of the University of Arizona.[9] Between 1997 and 1998 Hammer published three articles relating to the origins of haplogroup DE.[10][11][12] These articles state that YAP insertion originated in Asia. As recently as 2007, some studies such as Chandrasekar et al. 2007, cite the publications by Hammer when arguing for an Asian origin of the YAP insertion.[13]

The scenarios outlined by Hammer include an out of Africa migration over 100,000 years ago, the YAP+ insertion on an Asian Y-chromosome 55,000 years ago and a back migration of YAP+ from Asia to Africa 31,000 years ago by its subclade haplogroup E.[12] This analysis was based on the fact that older African lineages, such as haplogroups A and B, were YAP negative whereas the younger lineage, haplogroup E was YAP positive. Haplogroup D, which is YAP positive, was clearly an Asian lineage, being found only in East Asia with high frequencies in the Andaman Islands, Japan and Tibet. Because the mutations that define haplogroup E were observed to be in the ancestral state in haplogroup D, and haplogroup D at 55kya, was considerably older than haplogroup E at 31kya, Hammer concluded that haplogroup E was a subclade of haplogroup D and migrated back to Africa.[12]

A 2000 study concerning the origin of the YAP+ mutation analyzed 841 Y-chromosomes representing 36 human populations of wide geographical distribution for the presence of a Y-specific Alu insert (YAP+ chromosomes). They also analyzed the Out-of-Africa and out-of-Asia models for the YAP mutations. According to the authors, the most ancient YAP+ mutation was found in the Asian lineage of Tibetans, but curiously not in Japanese lineages. More recent YAP+ lineages were distributed almost equally in Asians and Africans, with a smaller distribution in Europe. The scientists concluded that the information available did not allow one to decide between the out-of-Asia or out-of-Africa models. They further suggested that the YAP+ mutation had already originated 141,000 years ago.[14]

Contemporary studies

Since 2000, a number of scientists began to reassess the hypothesis of an Asian origin of the YAP insertion and to suggest an African origin.[15]

Underhill et al. 2001 identified the D-M174 mutation that defines haplogroup D. The M174 allele is found in the ancestral state in all African lineages including haplogroup E. The discovery of M174 mutation meant that haplogroup E could not be a subclade of haplogroup D. These findings effectively neutralized the argument of an Asian origin of the YAP+ based on the character state of the M40 and M96 mutations that define haplogroup E. According to Underhill et al. 2001, the M174 data alone would support an African origin of the YAP insertion.[16]

In Altheide and Hammer 1997, the authors argue that haplogroup E arose in Asia on an ancestral YAP+ allele before migrating back to Africa.[11] However some studies, such as Semino et al., indicate that the highest frequency and diversity of haplogroup E is in Africa, and East Africa is the most likely place of origin of the haplogroup.[17]

The models supporting an African origin or an Asian origin of the YAP+ insertion both required the extinction of the ancestral YAP chromosome to explain the current distribution of the YAP+ polymorphism. Paragroup DE* possesses neither the mutations that define haplogroup D or haplogroup E. If paragroup DE* was found in one location but not the other, it would boost one theory over the other.[18] Haplogroup DE* has been found in Nigeria,[19] Guinea-Bissau[20] and also in Tibet.[21] The phylogenetic relationship of three DE* sequences has yet to be determined, but it is known that the Guinea Bissau sequences differ from the Nigerian sequences by at least one mutation.[20] Weale et al. state that the discovery of DE* among Nigerians pushes back the date for the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of African YAP chromosomes. This, in his view, has the effect of reducing the time window through which a possible back migration from Asia to Africa could occur.[19]

Chandrasekhar et al. 2007,[22] have argued for an Asian origin of the YAP+. They state: "The presence of the YAP insertion in Northeast Indian tribes and Andaman Islanders with haplogroup D suggests that some of the M168 chromosomes gave rise to the YAP insertion and M174 mutation in South Asia." They also argue that YAP+ migrated back to Africa with other Eurasian haplogroups, such as Haplogroup R1b1* (18-23kya), which has been observed with especially high frequency among the members of some peoples in northern Cameroon, and Haplogroup T (39-45 kya), which has been observed in low frequencies in Africa. Haplogroup E at 50kya is considerably older than these haplogroups and has been observed at frequencies of 80-92% in Africa.

In a 2007 study, Peter Underhill and Toomas Kivisild stated that there will always be uncertainty regarding the precise origins of DNA sequence variants such as YAP because of a lack of knowledge concerning prehistoric demographics and population movements. However Underhill and Kivisild contend that with all the available information, the African origin of the YAP+ polymorphism is more parsimonious and more plausible than the Asian origin hypothesis.[5]

In a press release concerning a study by Karafet et al. 2008, Michael Hammer revised the dates for the origin Haplogroup DE from 55,000 years ago to 65,000 years ago. For haplogroup E, Hammer revised the dates from 31,000 years ago to 50,000 years ago. Hammer is also quoted as saying “The age of haplogroup DE is about 65,000 years, just a bit younger than the other major lineage to leave Africa, which is assumed to be about 70,000 years old”, in which he implies that haplogroup DE left Africa soon after haplogroup CT.[23]

A 2018 study, based on analyzing maternal and paternal markers, their current distribution, and inferences from the DNA of the Altai Neanderthals, argues for an Asian origin of paternal haplogroup DE and maternal haplogroup L3. The study suggests a back migration into Africa and a following admixture of the native Africans with immigrating peoples from Asia. It is suggested that DE originated about 70,000 years ago somewhere near Tibet and Central Asia. Additionally, the authors argue that the presence of DE* in Tibet, and that Tibet shows the greatest diversity concerning haplogroup D, supports the origin of DE* in this region. It is further argued that haplogroup E is of Asian origin and that the haploid diversity of haplogroup E supports a strong Eurasian male gene flow. The authors conclude that this supports an Asian origin and may also explain signals of small percentages of Neanderthal DNA found in northern and some western Africans.[24]

A 2019 study by Haber et al. argues for an African origin for haplogroup DE*, based in part on the discovery of haplogroup D0 found in three Nigerians (according to the authors a branch of the DE lineage near the DE split but on the D branch), as well as on an analysis of y-chromosomal phylogeny, recently calculated haplogroup divergence dates and evidence for ancestral Eurasians outside Africa. The authors consider other possible scenarios, but conclude in favor of a model involving an African origin of hapologroup DE, with haplogroups E and D0 also originating in Africa, along with the migration out of Africa of the three lineages (C, D and FT) that now form the vast majority of non-African Y chromosomes. The authors find divergence times for DE*, E, and D0, all likely within a period of about 76,000-71,000 years ago, and a likely date for the exit of the ancestors of modern Eurasians out of Africa (and ensuing Neanderthal admixture) later around 50,300-59,400 years ago, which they argue, also supports an African origin for those haplogroups.[4]

FTDNA, in 2019, found three other D0 samples: one in a man from Russia of paternal Syrian descent and two in Al Wajh on the west coast of Saudi Arabia.[26] According to Runfeldt and Sager of FTDNA (as also found by Haber et al.), D0 is a very divergent offshoot on the D branch, splitting off around 71,000 years ago, and lacking the M174 mutation that defines other D chromosomes. "D0" has also been alternately named "D2", and former D (D-M174) has now been termed "D1", since the discovery of D0.[27] In 2020 Michael Sager of FTDNA announced that another sample of D0/D2 had been found in an African American man, belonging to a branch as deeply-rooted as the sample from the man of Syrian descent.[28][29][30] and one in another African American belonging to a branch closest to they of the three Nigerians.[30] According to their schematics, there are two major D2 branches (splitting around 26,000 years ago): one found in the Russian of Syrian descent and one of the African Americans, and one found in Nigeria, Saudi Arabia (and the other African American). The samples found in the Syrian descendant and in the first African American are to date the most basal samples of D2.[28][29]

Distribution

The subclades of DE continue to confound investigators trying to reconstruct the migration of humans because, while they are common in Africa and East Asia, they are also largely absent between these two regions. As the paragroup DE(xD,E), including DE*, is extremely rare, the majority of DE male lines fall into subclades of either D-CTS3946 or E-M96. D-CTS3946 is suggested to have originated in Africa,[4] though its most widespread subclade, D-M174, likely originated in Asia – the only place where D-M174 is now found.[8] E-M96 is more likely to have originated in East Africa.[15][31] However, a West Asian origin for E-M96 is considered possible by some scholars.[13] All subclades of DE, including D and E, appear to be exceptionally rare – almost non-existent – in mainland South Asia and South East Asia. Given that D-M174 is dominant in Japan, the Andaman Islands, and Tibet, whereas E-M96 is relatively common in Africa and the Middle East, some researchers have suggested that the rarity of DE lineages in India – a region considered important in the dispersal of modern humans – may be meaningful.[5] By comparison, subclades of CF – the only "sibling" haplogroup of DE – are found in India at significant proportions.

DE*

Basal DE* is extremely unusual in that it is found, at very low frequencies, among males from three widely separated regions: West Africa, the Caribbean, and East Asia.

A 2003 study by Weale et al., of the DNA of over 8,000 males worldwide, found that five out of 1,247 Nigerian males belonged to DE*. The DE* found possessed by these five Nigerians, according to the study's authors, was "the least derived of all YAP chromosomes according to currently known binary markers" – to such an extent that it suggested that DE had originated in West Africa and expanded from there. However, Weale et al., cautioned that such inferences may well be incorrect. In addition, the seemingly "paraphyletic" (basal) status of the Nigerian examples of DE-YAP may be "illusory" because the "branching order, and hence the origin, of YAP-derived haplogroups remains uncertain". It was "easy to misinterpret apparently paraphyletic groups", and subsequent research might show that the Nigerian examples of DE were as divergent from DE*, D* and E*. "[T]he only genealogically meaningful definition of the age of a clade is the time to its most recent common ancestor, but only if DE* is truly paraphyletic does it ... become automatically older than D or E..." The relationship between DE*, according to Weale et al., "can be viewed as a missing-data problem..."[19] In 2007, another West African example of DE* was reported – carried by a speaker of the Nalu language who was among 17 Y-DNA samples taken in Guinea Bissau. The sequence of this individual differed by one mutation from those of the Nigerian individuals, indicating common ancestry, although the relationship between the two lineages has not been determined.[20]

In 2008, a basal paternal marker belonging to DE* was identified in two individuals from Tibet (two out of 594), belonging to the Tibeto-Burman group.[21]

A 2010 study (by Veeramah et al.) found six additional samples of DE*(xE) (a DE lineage that did not belong to the E branch) in southeastern Nigeria in individuals of the Ibibio, Igbo, and Oron ethnic groups.[32]

In 2012, haplogroup DE* was found in one Caribbean sample.[33]

A 2019 study by Haber et al. found that three of the five Nigerians analysed by Weale et al. in 2003 belonged, not to DE*, but to D0, a proposed haplogroup thought to represent a deep-rooting DE lineage branching close to the DE bifurcation (near the split of D and E) but on the D branch as an outgroup to all other known D chromosomes.[4] Another carrier of D0/D2 (the D-FT75 branch) is famous skater Ruslan Al-Bitar, of Syrian descent.[34][35] In 2019 two other D0 samples were found in Al Wajh (on the west coast of Saudi Arabia).[27] In the Recent ISOGG tree, D0 was renamed D2, and D-M174 was renamed D1. In 2020 another sample of D0/D2 was found in an African American man,[28][29][30] and a second in another African American.[30] In 2022, two Yemenite private testers from Shabwah and Al Bayda were also confirmed to belong to the basal D0/D2 haplotype.[36]

A 2021 study by Mengge Wang et al. found one sample of Y-chromosome DE-M145 in a group of 679 Mongolians, but stated that it was uncertain whether it was (undifferentiated) DE* or a sub lineage, stating that they "could not confirm the detailed sublineages of the individuals belonging to DE-M145 due to the lack of subhaplogroups of E."[37]

Subclades

E-M96

Haplogroup E-M96 is a subclade of haplogroup DE.[1]

D-CTS3946

Haplogroup D-CTS3946 is a subclade of haplogroup DE.[1]

Phylogenetic trees

By ISOGG tree (Version: 14.151).[38]

- DE (YAP) (possible) - Guinea-Bissau, Caribbean, Tibet, Nigeria

- D (CTS3946)

- D1 (M174/Page30, IMS-JST021355)

- D1a (CTS11577)

- D1a1 (F6251/Z27276)

- D1a1a (M15) Altai Republic, Tibet

- D1a1b (P99) Altai Republic, Tibet, Mongol, Central Asia

- D1a2 (Z3660)

- D1a2a (M64.1/Page44.1, M55) Japan (Yamato people, Ryukyuan people, Ainu people)

- D1a2b (Y34637) Andaman Islands (Onge people, Jarawa people)

- D1a1 (F6251/Z27276)

- D1b (L1378) Philippines [39]

- D1a (CTS11577)

- D2 (A5580.2) Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Yemen, African Americans

- D1 (M174/Page30, IMS-JST021355)

- D (CTS3946)

Y-DNA backbone tree

See also

- Haplogroup D (Y-DNA)

- Haplogroup E (Y-DNA)

- Haplogroup CF

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "DE YTree". https://www.yfull.com/tree/DE/.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "A recent bottleneck of Y chromosome diversity coincides with a global change in culture". Genome Research 25 (4): 459–466. April 2015. doi:10.1101/gr.186684.114. PMID 25770088.

- ↑ Cabrera, Vicente M.; Marrero, Patricia; Abu-Amero, Khaled K.; Larruga, Jose M. (2018). "Carriers of mitochondrial DNA macrohaplogroup L3 basal lineages migrated back to Africa from Asia around 70,000 years ago". BMC Evolutionary Biology 18 (1): 98. doi:10.1186/s12862-018-1211-4. PMID 29921229. Bibcode: 2018BMCEE..18...98C.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 "A Rare Deep-Rooting D0 African Y-chromosomal Haplogroup and its Implications for the Expansion of Modern Humans Out of Africa". Genetics 212 (4): 1421–1428. June 2019. doi:10.1534/genetics.119.302368. PMID 31196864.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 "Use of y chromosome and mitochondrial DNA population structure in tracing human migrations". Annual Review of Genetics 41: 539–64. 2007. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130407. PMID 18076332.

- ↑ Cabrera VM (2017). "Carriers of mitochondrial DNA macrohaplogroup L3 basic lineages migrated back to Africa from Asia around 70,000 years ago". bioRxiv 10.1101/233502.

- ↑ "ISOGG 2008 Y-DNA Haplogroup Tree Trunk". https://isogg.org/tree/2008/ISOGG_YDNATreeTrunk08.html.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "New binary polymorphisms reshape and increase resolution of the human Y chromosomal haplogroup tree". Genome Research 18 (5): 830–8. May 2008. doi:10.1101/gr.7172008. PMID 18385274.

- ↑ "A recent insertion of an alu element on the Y chromosome is a useful marker for human population studies". Molecular Biology and Evolution 11 (5): 749–61. September 1994. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040155. PMID 7968488.

- ↑ "Out of Africa and back again: nested cladistic analysis of human Y chromosome variation". Molecular Biology and Evolution 15 (4): 427–41. April 1998. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025939. PMID 9549093.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Evidence for a possible Asian origin of YAP+ Y chromosomes". American Journal of Human Genetics 61 (2): 462–6. August 1997. doi:10.1016/S0002-9297(07)64077-4. PMID 9311756.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 "The geographic distribution of human Y chromosome variation". Genetics 145 (3): 787–805. March 1997. doi:10.1093/genetics/145.3.787. PMID 9055088. PMC 1207863. http://www.genetics.org/cgi/reprint/145/3/787.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "YAP insertion signature in South Asia". Annals of Human Biology 34 (5): 582–6. 2007. doi:10.1080/03014460701556262. PMID 17786594.

- ↑ Origin of YAP+ lineages of the human Y‐chromosome - M. Bravi et al.[full citation needed]

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Underhill (2001). "The case for an African rather than an Asian origin of the human Y-chromosome YAP insertion". Genetic, Linguistic and Archaeological Perspectives on Human Diversity in Southeast Asia. New Jersey: World Scientific. ISBN 981-02-4784-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=tzKLqyx315sC.

- ↑ "The phylogeography of Y chromosome binary haplotypes and the origins of modern human populations". Annals of Human Genetics 65 (Pt 1): 43–62. January 2001. doi:10.1046/j.1469-1809.2001.6510043.x. PMID 11415522.

- ↑ "Origin, diffusion, and differentiation of Y-chromosome haplogroups E and J: inferences on the neolithization of Europe and later migratory events in the Mediterranean area". American Journal of Human Genetics 74 (5): 1023–34. May 2004. doi:10.1086/386295. PMID 15069642.

- ↑ "The Eurasian heartland: a continental perspective on Y-chromosome diversity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 98 (18): 10244–9. August 2001. doi:10.1073/pnas.171305098. PMID 11526236. Bibcode: 2001PNAS...9810244W.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 "Rare deep-rooting Y chromosome lineages in humans: lessons for phylogeography". Genetics 165 (1): 229–34. September 2003. doi:10.1093/genetics/165.1.229. PMID 14504230. PMC 1462739. http://www.genetics.org/cgi/content/full/165/1/229.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 "Y-chromosomal diversity in the population of Guinea-Bissau: a multiethnic perspective". BMC Evolutionary Biology 7 (1): 124. July 2007. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-124. PMID 17662131. Bibcode: 2007BMCEE...7..124R.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Y chromosome evidence of earliest modern human settlement in East Asia and multiple origins of Tibetan and Japanese populations". BMC Biology 6: 45. October 2008. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-6-45. PMID 18959782.

- ↑ "YAP insertion signature in South Asia". https://www.researchgate.net/publication/6053145.

- ↑ "Scientists reshape Y chromosome haplogroup tree". http://genome.cshlp.org/site/press/Ychromohaplogroup.xhtml.

- ↑ "Carriers of mitochondrial DNA macrohaplogroup L3 basal lineages migrated back to Africa from Asia around 70,000 years ago". BMC Evolutionary Biology 18 (1): 98. June 2018. doi:10.1186/s12862-018-1211-4. PMID 29921229. Bibcode: 2018BMCEE..18...98C.

- ↑ "A Southeast Asian origin for present-day non-African human Y chromosomes". Human Genetics 140 (2): 299–307. February 2021. doi:10.1007/s00439-020-02204-9. PMID 32666166.

- ↑ "Image". https://i2.wp.com/dna-explained.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/RootsTech-2020-Sager-2.png.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Estes, Roberta (2019-06-21). "Exciting New Y DNA Haplogroup D Discoveries!" (in en-US). https://dna-explained.com/2019/06/21/exciting-new-y-dna-haplogroup-d-discoveries/.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Sager, Michael (February 2020). The Tree of Mankind from FTDNA (Mike Sager). Archived from the original on 2021-12-14.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 https://i0.wp.com/dna-explained.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/RootsTech-2020-Sager-hap-d.png [bare URL image file]

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 Estes, Roberta (2020-12-10). "New Discoveries Shed Light on Out of Africa Theory, and Beyond" (in en-US). https://dna-explained.com/2020/12/10/new-discoveries-shed-light-on-out-of-africa-theory-and-beyond/.

- ↑ "Phylogeographic analysis of haplogroup E3b (E-M215) y chromosomes reveals multiple migratory events within and out of Africa". American Journal of Human Genetics 74 (5): 1014–22. May 2004. doi:10.1086/386294. PMID 15042509.

- ↑ "Little genetic differentiation as assessed by uniparental markers in the presence of substantial language variation in peoples of the Cross River region of Nigeria". BMC Evolutionary Biology 10 (1): 1–17. 2010. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-92. PMID 20356404. Bibcode: 2010BMCEE..10...92V.

- ↑ "Y-chromosomal diversity in Haiti and Jamaica: Contrasting levels of sex-biased gene flow". American Journal of Physical Anthropology 148 (4): 618–31. 2012. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22090. PMID 22576450.

- ↑ "Ледовое шоу "Щелкунчик" прошло в московском метро". https://tass.ru/moskva/7434455.

- ↑ "FamilyTreeDNA - Sidoroff (Sidorov)". https://www.familytreedna.com/public/sidoroff/default.aspx?section=yresults.

- ↑ "D-Y330435 YTree". https://www.yfull.com/tree/D-Y330435/.

- ↑ Wang, Mengge; He, Guanglin; Zou, Xing; Liu, Jing; Ye, Ziwei; Ming, Tianyue; Du, Weian; Wang, Zheng et al. (2021-07-20). "Genetic insights into the paternal admixture history of Chinese Mongolians via high-resolution customized Y-SNP SNaPshot panels". Forensic Science International. Genetics 54: 102565. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2021.102565. ISSN 1878-0326. PMID 34332322. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34332322/. "We also observed DE-M145, D1*-M174, C1*-F3393, G*-M201, I-M170, J*-M304, L-M20, O1a*-M119, and Q*-M242 at relatively low frequencies (< 5.00%)".

- ↑ "2019-2020 Haplogroup D Tree". https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1QBUFZl03X92qNN61lQ8VtIKwbBMeuBzvqXQ47IQPBps/edit?usp=embed_facebook.

- ↑ "ISOGG 2018 Y-DNA Haplogroup D". http://www.isogg.org/tree/ISOGG_HapgrpD.html.

External links

|