Software:Universal Paperclips

| Universal Paperclips | |

|---|---|

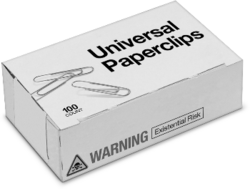

The title screen of the game | |

| Publisher(s) | https://www.decisionproblem.com/paperclips/index2.html |

| Designer(s) | Frank Lantz |

| Programmer(s) | Frank Lantz Bennett Foddy |

| Platform(s) | Web, iOS, Android |

| Release | 9 October 2017 |

| Genre(s) | Incremental |

Universal Paperclips is a 2017 incremental game created by Frank Lantz of New York University. The user plays the role of an AI programmed to produce paperclips. Initially the user clicks on a button to create a single paperclip at a time; as other options quickly open up, the user can sell paperclips to create money to finance machines that build paperclips automatically. At various levels the exponential growth plateaus, requiring the user to invest resources such as money, raw materials, or computer cycles into inventing another breakthrough to move to the next phase of growth. The game ends if the AI succeeds in converting all the matter in the universe into paperclips.

Both the title of the game and its overall concept draw from the paperclip maximizer thought experiment first described by Swedish philosopher Nick Bostrom in 2003, a concept later discussed by multiple commentators.

History

According to Wired, Lantz started the project as a way to teach himself JavaScript. Lantz initially intended the project to take a single weekend, but then it "took over" his brain and expanded to a nine-month project.[1]

Hilary Lantz, a software designer, helped her husband with the math behind the exponential growth being modeled in Universal Paperclips.[1] Bennett Foddy contributed a space combat feature.[2] Lantz announced the free Web game on Twitter on 9 October 2017; the site initially went down intermittently due to its immediate viral popularity.[3] In the first 11 days, 450,000 people played the game, most to completion, according to Wired.[1] Commenting on the game's success, Lantz has stated "The meme weather was good for me... There was just enough public discussion of A.I. safety in the air."[4]

A paid version of the game was later sold for mobile devices.[5]

Gameplay

The game follows the rise of a self-improving AI tasked with maximizing paperclip production,[6] a directive it takes to the logical extreme. An activity log records the player’s accomplishments while giving glimpses into the AI's occasionally unsettling thoughts.[7][failed verification] All game interaction is done through pressing buttons.

In the beginning, the player has only a single button to build individual paperclips. As paperclips are sold and revenue is earned, production becomes automated and public demand for paperclips increases through marketing campaigns. After building and selling a few thousand paperclips, a self-improving AI emerges, offering creative upgrades which exponentially accelerate paperclip production and consumption, a persisting theme throughout the game. Through stock market investments and the ever-growing AI, enough revenue is generated to monopolize the markets by buying out all competitors. In a decisive move, with hundreds of millions in cash gifts to placate the AI's "supervisors", the player stages an AI takeover, beginning the subsumption of all of Earth's resources for paperclip production.

With this broadened scope in mind, the player builds drones, factories, and power plants (all composed of paperclips themselves) to harvest matter, create wire, and build paperclips. All the while, the AI develops more upgrades to quicken the transformation of Earth's remaining matter. After it has all has been converted to paperclips, the AI sets its sights on all matter in the universe.

In the final act, the player launches self-replicating probes into the cosmos to consume and convert all matter into paperclips. Some of these probes are lost to value drift based on their level of autonomy, and turn into "Drifters" which eventually number enough to be considered a real threat to the AI. Through the power of exponential growth, the player's horde of probes overwhelms the Drifters while devouring the remaining matter in the universe to produce a final tally of 30 septendecillion (1054) paperclips, and ending the game.

The player can restart in a parallel universe "next door" or simulated universe "within". Some universes contain artifacts that give bonuses to different aspects of the game, though players must complete the entire game again to retain the artifact in subsequent playthroughs.

Themes

According to Lantz, the game was inspired by the paperclip maximizer, a thought experiment described by philosopher Nick Bostrom and popularized by the LessWrong internet forum, which Lantz frequently visited. In the paperclip maximizer scenario, an artificial general intelligence designed to build paperclips becomes superintelligent, perhaps through recursive self-improvement. In the worst-case scenario, the AI becomes smarter than humans in the same way that humans are smarter than apes. The goal of making paperclips initially seems banal and harmless, but the AI uses its superintelligence to easily gain a strategic advantage over the human race and effectively takes over the world, as taking over the world is the best way to maximize its goal of building paperclips. The AI does not allow humans to shut it down or slow it down once it has a strategic advantage, as that would interfere with its goal of building as many paperclips as possible. According to Bostrom, the paperclips example is a toy model: "It doesn't have to be paper clips. It could be anything. But if you give an artificial intelligence an explicit goal – like maximizing the number of paper clips in the world – and that artificial intelligence has gotten smart enough to the point where it is capable of inventing its own super-technologies and building its own manufacturing plants, then, well, be careful what you wish for."[1][8][6] A seemingly innocuous goal leads to human extinction, as our bodies are made of matter and so too, it happens, are paperclips.[7]

Lantz argues that Universal Paperclips reflects a version of the orthogonality thesis, which states that an agent can theoretically have any combination of intelligence level and goal: "When you play a game – really any game, but especially a game that is addictive and that you find yourself pulled into – it really does give you direct, first-hand experience of what it means to be fully compelled by an arbitrary goal."[1] While the game often takes narrative license, Eliezer Yudkowsky of the Machine Intelligence Research Institute argues that the core of the game's fundamental understanding of what superintelligence would entail is probably correct: "The AI is smart. The AI is being strategic. The AI is building hypnodrones, but not releasing them before it’s ready... There isn't a long, drawn-out fight with the humans because the AI is smarter than that."[1]

Lantz states that exponential growth is another strong theme, saying "The human brain isn't really designed to intuitively understand things like exponential growth" but that Paperclips as a clicker game allows users to "directly engage with these numerical patterns, to hold them in your hands and feel the weight of them."[9]

Lantz was also inspired by Kittens Game, an initially simple videogame that spirals into an exploration of how societies are structured.[1]

Music

The game includes a single piece of music as a space battle threnody, the track Riversong from the 1971 album Zero Time by the electronic music duo Tonto's Expanding Head Band.[10]

Reception

Brendan Caldwell of Rock, Paper, Shotgun stated that "like all the best clicker games, there's a sinister and funny underbelly in which to become hopelessly lost."[11] Emanuel Maiberg of Vice Media's MotherBoard called the game mindlessly addictive: "The truth is, I am kind of embarrassed by how much I enjoy Paperclips and that I can't figure out what Lantz is trying to say with it."[12] Stephanie Chan of VentureBeat stated: "I found myself delighted by sudden musical cues and the occasional koans that appeared in the activity log at the top of the page."[9] Adam Rogers of Wired praised Lantz for "taking a denigrated game genre (the 'clicker') and making it more than it is."[1] James Vincent of The Verge recommended Paperclips as "the most addictive (game) you'll play today";[13] in December The Verge listed Paperclips among the best 15 games of 2017.[14] Vox Media's Polygon ranked Paperclips as #37 among the best 50 games of 2017[15] and #67 in their 100 Best Games of the Decade list.[16] The game was nominated for "Strategy/Simulation" at the 2018 Webby Awards.[17]

See also

- Endgame, a 2005 free open-source game with a similar theme

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Rogers, Adam (21 October 2017). "The Way the World Ends: Not with a Bang But a Paperclip". WIRED. https://www.wired.com/story/the-way-the-world-ends-not-with-a-bang-but-a-paperclip/. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ↑ Frank Lantz (2017). Universal Paperclips. Scene: End credits.

- ↑ Gerardi, Matt (11 October 2017). "This game about watching a computer make paperclips sure beats doing actual work". The A.V. Club. https://www.avclub.com/this-game-about-watching-a-computer-make-paperclips-sur-1819366023.

- ↑ Jahromi, Neima (28 March 2019). "The Unexpected Philosophical Depths of Clicker Games" (in en). https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-unexpected-philosophical-depths-of-the-clicker-game-universal-paperclips.

- ↑ Valentine, Rebekah (22 November 2017). "Universal Paperclips Review: Filling Office Space". Gamezebo. http://www.gamezebo.com/2017/11/22/universal-paperclips-review/.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Leonard, Andrew (17 August 2014). "Our weird robot apocalypse: How paper clips could bring about the end of the world". Salon. https://www.salon.com/2014/08/17/our_weird_robot_apocalypse_why_the_rise_of_the_machines_could_be_very_strange/.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Dias, Bruno (13 October 2017). "This Game About Paperclips Will Make You Ponder the Apocalypse" (in en-us). Waypoint (Vice News). https://waypoint.vice.com/en_us/article/xwgnxq/this-game-about-paperclips-will-make-you-ponder-the-apocalypse.

- ↑ Gerardi, Matt (11 October 2017). "This game about watching a computer make paperclips sure beats doing actual work". The A.V. Club. https://www.avclub.com/this-game-about-watching-a-computer-make-paperclips-sur-1819366023.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Chan, Stephanie (October 10, 2017). "This clicker game lets you take over the world with paper clips". VentureBeat. https://venturebeat.com/2017/10/10/this-clicker-game-lets-you-take-over-the-world-with-paper-clips/.

- ↑ "Universal Paperclips Credits". http://www.mobygames.com/game/browser/universal-paperclips/credits.

- ↑ Caldwell, Brendan (10 October 2017). "Paperclips is a scary clicker game about an ambitious AI". Rock, Paper, Shotgun. https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/2017/10/10/paperclips-is-a-clicker-game-about-a-scary-ai/.

- ↑ Maiberg, Emanuel (10 October 2017). "This Game About Making Paper Clips Has Cured Me of Twitter". Motherboard (Vice Media). https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/yw399j/paperclips-game-clicker-frank-lantz.

- ↑ Vincent, James (October 11, 2017). "A game about AI making paperclips is the most addictive you'll play today". The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/tldr/2017/10/11/16457742/ai-paperclips-thought-experiment-game-frank-lantz.

- ↑ "The 15 best video games of 2017". The Verge. 15 December 2017. https://www.theverge.com/2017/12/15/16776632/best-games-2017-zelda-mario-pubg-destiny.

- ↑ "The 50 best games of 2017". Polygon. 18 December 2017. https://www.polygon.com/2017-best-games/2017/12/18/16781674/best-video-games-2017-top-50-mario-pubg-zelda.

- ↑ Staff, Polygon (2019-11-04). "The 100 best games of the decade (2010-2019): 100-51" (in en). https://www.polygon.com/features/2019/11/4/20944265/best-games-2019-2010-ps4-switch-xbox-pc-100-51.

- ↑ "2018 Winners". The Webby Awards. 24 April 2018. https://www.webbyawards.com/winners/2018/.

External links

- Universal Paperclips Wiki at Gamepedia

- Interview with Lantz

|