Religion:Great Lent

| Part of a series on the |

| Eastern Orthodox Church |

|---|

| Overview |

Great Lent, or the Great Fast (Greek: Μεγάλη Τεσσαρακοστή or Μεγάλη Νηστεία, meaning "Great 40 Days", and "Great Fast", respectively), is the most important fasting season of the church year within many denominations of Eastern Christianity. It is intended to prepare Christians for the greatest feast of the church year, Pascha (Easter).[1]

Great Lent shares its origins with the Lent of Western Christianity and has many similarities with it. There are some differences in the timing of Lent, besides calculating the date of Easter and how it is practiced, both liturgically in the public worship of the church and individually.

One difference between Eastern Christianity and Western Christianity is the calculation of the date of Easter (see Computus). Most years, the Eastern Pascha falls after the Western Easter, and it may be as much as five weeks later; occasionally, the two dates coincide. Like Western Lent, Great Lent itself lasts for forty days, but in contrast to the West, Sundays are included in the count.

Great Lent officially begins on Clean Monday, seven weeks before Pascha (Ash Wednesday is not observed in Eastern Christianity), and runs for 40 continuous days, concluding with the Presanctified Liturgy on Friday of the Sixth Week. The next day is called Lazarus Saturday, the day before Palm Sunday. Thus, in case the Easter dates coincide, Clean Monday is two days before Ash Wednesday.

Fasting continues throughout the following week, known as Passion Week or Holy Week, and does not end until after the Paschal Vigil early in the morning of Pascha (Easter Sunday).

Purpose

The purpose of Great Lent is to prepare the faithful to not only commemorate, but to enter into the Passion and Resurrection of Jesus. The totality of the Byzantine Rite life centers around the Resurrection.[2] Great Lent is intended to be a "workshop" where the character of the believer is spiritually uplifted and strengthened; where their life is rededicated to the principles and ideals of the Gospel; where fasting and prayer culminate in deep conviction of life; where apathy and disinterest turn into vigorous activities of faith and good works.

Lent is not for the sake of Lent itself, as fasting is not for the sake of fasting. Rather, these are means by which and for which the individual believer prepares himself to reach for, accept and attain the calling of their Savior. Therefore, the significance of Great Lent is highly appraised, not only by the monks who gradually increased the length of time of the Lent, but also by the lay people themselves. The Eastern Orthodox lenten rules are the monastic rules. These rules exist not as a Pharisaic law, "burdens grievous to be borne" Luke 11:46, but as an ideal to be striven for; not as an end in themselves, but as a means to the purification of heart, the enlightening of mind, the liberation of soul and body from sin, and the spiritual perfection crowned in the virtue of love towards God and man.

In the Byzantine Rite, asceticism is not exclusively for the "professional" religious, but for each layperson as well, according to their strength. As such, Great Lent is a sacred Institute of the Church to serve the individual believer in participating as a member of the Mystical Body of Christ. It provides each person an annual opportunity for self-examination and improving the standards of faith and morals in their Christian life. The deep intent of the believer during Great Lent is encapsulated in the words of Saint Paul: "forgetting those things which are behind, and reaching forth unto those things which are before, I press toward the mark for the prize of the high calling of God in Christ Jesus" (Philippians 3:13-14).

Through spending more time than usual in prayer and meditation on the Holy Scripture and the Holy Traditions of the Church, the believer in Christ becomes through the grace of God more godlike. The emphasis towards this period differs somewhat from Western Christianity- the Eastern focus is less on repentance and more of an attempt to recapture humanity's original state.

Observance

Self-discipline

Observance of Great Lent is characterized by fasting and abstinence from certain foods, intensified private and public prayer, self-examination, confession, personal improvement, repentance and restitution for sins committed, and almsgiving. Fasting is defined as not consuming food until evening (at sundown).[3] The Lenten supper that is eaten after the fast is broken in the evening must not include certain foods.[3] Foods most commonly abstained from are meat, fish, eggs, dairy products, wine, and oil. According to some traditions, only olive oil is abstained from; in others, all vegetable oils.[4]

While wine and oil are permitted on Saturdays, Sundays, and a few feast days, and fish is permitted on Palm Sunday as well as the Annunciation when it falls before Palm Sunday, and caviar is permitted on Lazarus Saturday, meat and dairy are prohibited entirely until the fast is broken on Easter.[5] Additionally, Eastern Orthodox Christians traditionally abstain from sexual relations during Lent.[6]

Besides the additional liturgical celebrations described below, Christians are expected to pay closer attention to and increase their private prayer.[citation needed] According to Byzantine Rite theology, when asceticism is increased, prayer must be increased also. The Church Fathers[which?] have referred to fasting without prayer as "the fast of the demons"[citation needed] since the demons do not eat according to their incorporeal nature, but neither do they pray.

Liturgical observances

Great Lent is unique in that, liturgically, the weeks do not run from Sunday to Saturday, but rather begin on Monday and end on Sunday, and most weeks are named for the lesson from the Gospel which will be read at the Divine Liturgy on its concluding Sunday. This is to illustrate that the entire season is anticipatory, leading up to the greatest Sunday of all: Pascha.

During the Great Fast, a special service book is used, known as the Lenten Triodion, which contains the Lenten texts for the Daily Office (Canonical Hours) and Liturgies. The Triodion begins during the Pre-Lenten period to supplement or replace portions of the regular services. This replacement begins gradually, initially affecting only the Epistle and Gospel readings, and gradually increases until Holy Week when it entirely replaces all other liturgical material. During the Triduum even the Psalter is eliminated, and all texts are taken exclusively from the Triodion. The Triodion is used until the lights are extinguished before midnight at the Paschal Vigil, at which time it is replaced by the Pentecostarion, which begins by replacing the normal services entirely (during Bright Week) and gradually diminishes until the normal services resume following the Afterfeast of Pentecost.

On the weekdays of Great Lent, the full Divine Liturgy is not celebrated, because the joy of the Eucharist (literally "Thanksgiving") is contrary to the attitude of repentance which predominates on these days. Since it is considered especially important to receive the Holy Mysteries (Holy Communion) during this season, the Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts—also called the Liturgy of St. Gregory the Dialogist— may be celebrated on weekdays.

This service starts with Vespers during which a portion of the Body and Blood of Christ, which was reserved the previous Sunday, is brought to the prothesis table. This is followed by a solemn great entrance where the Holy Mysteries are brought to the altar table, and then, skipping the anaphora (eucharistic prayer), the outline of remainder of the divine liturgy is followed, including holy communion. Most parishes and monasteries celebrate this liturgy only on Wednesdays, Fridays and feast days, but it may be celebrated on any weekday of Great Lent.

Because the divine liturgy is not celebrated on weekdays, the Typica occupies its place in the canonical hours, whether or not a liturgy is celebrated at vespers. On Saturday and Sunday the Divine Liturgy may be celebrated as usual. On Saturdays, the usual Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom is celebrated; on Sundays the longer Divine Liturgy of St. Basil the Great is used.

The services of the Canonical Hours are much longer during Great Lent and the structure of the services is different on weekdays. The usual evening small compline is replaced by the much longer service of Great Compline. While in the Russian tradition Great Compline is used on Friday night (though some parts are read rather than sung and some Lenten material is replaced by non-Lenten hymns), in the Greek practice, ordinary Compline is used together with, on the first four weeks, a quarter of the Akathist to the Theotokos. On the fifth Saturday, known as the Saturday of the Akathist, everywhere, the entire Akathist is sung at Matins.

In “The Typikon Decoded”, Archbishop Job Getcha offers this comparison of the commemorations associated with the Sundays of Great Lent in the “Ancient Triodion”. These more ancient commemorations are retained in the hymnography still in use for the “Contemporary” Sundays of St Gregory Palamas, St John of the Ladder, and St Mary of Egypt. On each of these, the troparia of the 1st Canon at Matins reference the more ancient commemoration, the Prodigal Son, Good Samaritan, and the Rich Man and Lazarus respectively.

During Palm Week, between the Sunday of St Mary of Egypt and Lazarus Saturday, the 1st Canon at Matins on each weekday references the parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus as a parallel to the Lazarus of Bethany who falls ill and is raised from the dead after four days in the tomb (John 11:1-45). [7]

| Ancient Triodia | Contemporary Triodia |

|---|---|

| (Jerusalem Lectionary) | (Constantinople Lectionary) |

| Sunday of the Holy Prophets | Sunday of Triumph of Orthodoxy |

| Sunday of the Prodigal Son | Sunday of St Gregory Palamas |

| Sunday of the Publican & Pharisee | Veneration of the Cross |

| Sunday of the Good Samaritan | Sunday of St John Climacus (of "The Ladder") |

| Sunday of the Rich Man & Lazarus | Sunday of St Mary of Egypt |

| Palm Sunday | Palm Sunday |

Theme of Lenten joy

A difference between the Eastern and Western observances is that while in the West the chanting of Alleluia ceases during Lent, in the East its use is increased. This is because for Christians, fasting should be joyous (cf. Matthew 6:16), and the sense of unworthiness must always be tempered with hope in God's forgiveness.[8]

In fact, days which follow the Lenten pattern of services are referred to as "days with Alleluia". This theme of "Lenten joy" is also found in many of the hymns of the Triodion, such as the stichera which begin with the words: "The Lenten Spring has dawned!..." (Vespers Aposticha, Wednesday of Maslenitsa) and "Now is the season of repentance; let us begin it joyfully, O brethren..." (Matins, Second Canon, Ode 8, Monday of Maslenitsa).

The making of prostrations during the services increases as well. The one prayer that typifies the Lenten services is the Prayer of Saint Ephrem, which is said at each service on weekdays, accompanied by full prostrations. One translation of it reads:

O Lord and master of my life! a spirit of idleness, despondency, ambition and idle-talking, give me not.

But rather, a spirit of chastity, humble-mindedness, patience and charity, bestow upon me Thy servant.

Yea, my king and Lord, grant me to see my own failings and refrain from judging others: For blessed art Thou unto ages of ages. Amen.

The public reading of Scripture is increased during Great Lent. The Psalter (Book of Psalms), which is normally read through once a week, is read through twice each week for the six weeks prior to Holy Week. Readings from the Old Testament are also increased, with the Books of Genesis, Proverbs and Isaiah being read through almost in their entirety at the Sixth Hour and Vespers. During Cheesefare Week, the readings at these services are taken from Joel and Zechariah, while during Holy Week they are from Exodus, Ezekiel and Job.

Uniquely, on weekdays of Great Lent there is no public reading of the Epistles or Gospels. This is because the readings are particular to the divine liturgy, which is not celebrated on weekdays of Great Lent. There are, however, Epistles and Gospels appointed for each Saturday and Sunday.

Prayer for the dead

During the Great Fast, the church also increases its prayer for the dead, not only reminding the believer of his own mortality, and thus increasing the spirit of penitence, but also to remind him of his Christian obligation of charity in praying for the departed. A number of Saturdays during Great Lent are Saturdays of the Dead, with many of the hymns of the Daily Office and at the Divine Liturgy dedicated to remembrance of the departed. These Saturdays are:

- The Saturday of Meatfare Week

- The Second Saturday of Great Lent

- The Third Saturday of Great Lent

- The Fourth Saturday of Great Lent

In addition, the Lity, a brief prayer service for the departed, may be served on each weekday of Great Lent, provided there is no feast day or special observance on that day.

Feast days

Since the season of Great Lent is moveable, beginning on different dates from year to year, accommodation must be made for various feast days on the fixed calendar (Menaion) which occur during the season. When these feasts fall on a weekday of Great Lent, the normal Lenten aspect of the services is lessened to celebrate the solemnity.

The most important of these fixed feasts is the Great Feast of the Annunciation (March 25), which is considered to be so important that it is never moved, even if it should fall on the Sunday of Pascha itself, a rare and special occurrence which is known as Kyrio-Pascha. The fast is also lessened, and the faithful are allowed to eat fish, unless it is Good Friday or Holy Saturday. Whereas on other weekdays of Great Lent, no celebration of the Divine Liturgy is permitted, there is a Liturgy (usually the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom) celebrated on Annunciation—even if it falls on Good Friday.

When the feast day of the patron saint of the parish church or monastery falls on a weekday of Great Lent, there is no liturgy (other than the Presanctified), but fish is allowed at the meal. In some churches the feast of a patron saint is moved to the nearest Saturday (excluding the Saturday of the Akathist), and in other churches, it is celebrated on the day of the feast itself.

When some other important feast occurs on a weekday, such as the First and Second Finding of the Head of John the Baptist (February 24), the Forty Martyrs of Sebaste (March 9), etc., it is usually combined with the Lenten service, and wine and oil are allowed at the meal.

Regardless of the rank of the feast being celebrated, the Lenten hymns contained in the Triodion are never omitted, but are always chanted in their entirety, even on the feast of the Annunciation.

On the Saturdays, Sundays, and a number of weekdays during Great Lent, the service materials from the Triodion leave no room for the commemoration of the Saint of the day from the Menaion. In order that their services not be completely forgotten, a portion of them (their canon at Matins, and their stichera from "Lord I Have Cried" at Vespers) is chanted at Compline.

Readings

In addition to the added readings from Scripture, spiritual books by the Church Fathers are recommended during the Fast.

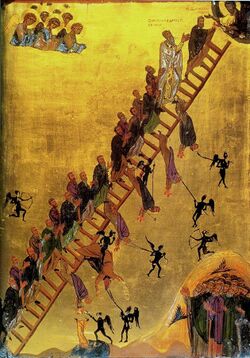

One book commonly read during Great Lent, particularly by monastics, is The Ladder of Divine Ascent, which was written in about the 7th century by St. John of the Ladder when he was the Hegumen (Abbot) of Saint Catherine's Monastery on Mount Sinai. The Ladder is usually read in the trapeza (refectory) during meals, but it may alternatively be read during the Little Hours on weekdays so that everyone can hear. Many of the laity also read The Ladder privately during Great Lent.

The theme of The Ladder is not Great Lent itself, but rather it deals with the ascent of the soul from earth to heaven. That is, from enslavement to the passions to the building up of the virtues and its eventual theosis (union with God), which is the goal of Great Lent.

Besides the Ladder, in some monasteries the Paradise of the Holy Fathers by Palladius and the penitential sermons of St. Ephrem the Syrian are read during Matins.

Outline

Liturgically, the period of the Triodion can be divided into three sections: (1) the Pre-Lenten period, (2) the Great Forty Days, and (3) Holy Week.

Pre-Lenten period

Before the forty days of Great Lent commence, there is a three-week Pre-Lenten season, to prepare the faithful for the spiritual work they are to accomplish during the Great Fast. During this period many of the themes which will be developed in the liturgical texts of the forty days are introduced. Each week runs from Monday to Sunday and is named for the Gospel theme of the Sunday which concludes it.

In the Slavic tradition, with the addition of Zacchaeus Sunday, some regard the pre-Lenten period as lasting four weeks, but there are no liturgical indications that the week following the fifth Sunday before Lent (whether preceded by Zacchaeus Sunday or otherwise) is in any way Lenten, because Zacchaeus Sunday falls outside the Triodion, the liturgical book which governs the pre-Lenten period and Lent itself.

Zacchaeus Sunday

In the Slavic liturgical traditions, Zacchaeus Sunday occurs on the fifth Sunday before the beginning of Great Lent (which starts on a Monday). Though there are no materials provided in the Lenten Triodion for this day, it is the very first day that is affected by the date of the upcoming Pascha (all the preceding days having been affected by the previous Pascha). This day has one sole Pre-Lenten feature: the Gospel reading is always the account of Zacchaeus from Luke 19:1-10, for which reason this Sunday is referred to as "Zacchaeus Sunday" (though the week before is not called "Zacchaeus week").

This reading actually falls at the end of the lectionary cycle, being assigned to the 32nd Week after Pentecost. However, depending upon the date of the upcoming Pascha, the readings of the preceding weeks are either skipped (if Pascha will be early) or repeated (if it will be late) so that the readings for the 32nd Sunday after Pentecost always occur on the Sunday preceding the Week of the Publican and the Pharisee.

In the Byzantine ("Greek") liturgical traditions, the Gospel reading for Zacchaeus remains in the normal lectionary cycle and does not always fall on the fifth Sunday before Lent. In fact, it usually falls a few weeks before, and the fifth Sunday before Lent is known as the Sunday of the Canaanite Woman after the story in Matthew 15:21-28.

The Lenten significance of the Gospel account of Zacchaeus is that it introduces the themes of pious zeal (Zacchaeus' climbing up the sycamore tree; Jesus' words: "Zacchaeus, make haste"), restraint (Jesus' words: "come down"), making a place for Jesus in the heart ("I must abide at thy house"), overcoming gossip ("And when they saw it, they all murmured, saying, That he was gone to be guest with a man that is a sinner"), repentance and almsgiving ("And Zacchaeus stood, and said unto the Lord: Behold, Lord, the half of my goods I give to the poor; and if I have taken any thing from any man by false accusation, I restore him fourfold"), forgiveness and reconciliation ("And Jesus said unto him, This day is salvation come to this house, forsomuch as he also is a son of Abraham"), and the reason for the Passion and Resurrection ("For the Son of man is come to seek and to save that which was lost").

The Epistle reading for Zacchaeus Sunday is 1 Timothy 4:9-15, which in and of itself has no Lenten theme, other than as an admonition to righteous behaviour.

Publican and Pharisee

The reading on the Sunday which concludes this week is the Parable of the Publican and the Pharisee (Luke 18:10-14). The Sunday of the Publican and the Pharisee is the first day the Lenten Triodion is used (at Vespers or All-Night Vigil on Saturday night), though it is only used for the Sunday services, with nothing pertaining to weekdays or Saturday. The theme of the hymns and readings on this Sunday is dedicated to the lessons to be learned from the parable: that righteous actions alone do not lead to salvation, that pride renders good deeds fruitless, that God can only be approached through a spirit of humility and repentance, and that God justifies the humble rather than the self-righteous. The week which follows the Sunday of the Publican and the Pharisee is a fast-free week, to remind the faithful not to be prideful in their fasting as the Pharisee was (Luke 18:12).

The Sunday of the Publican and the Pharisee is also the first day that structural changes (as opposed to simply substituting Lenten hymns for normal hymns from the octoechos or menaion) are made to the Sunday services. For example, there begins to be a significant 'split' after the Great Prokimenon at Vespers that night.

Prodigal Son

The theme of this week is the Parable of the Prodigal Son (Luke 15:11-32). Again, the Triodion does not give propers for the weekdays. The Gospel Reading on Sunday lays out one of the most important themes of the Lenten season: the process of falling into sin, realization of one's sinfulness, the road to repentance, and finally reconciliation, each of which is illustrated in the course of the parable.

The week following is the only week of the Triodion on which there is normal fasting (i.e. no meat, fish, wine, oil or animal products on Wednesday or Friday except if an important feast such as the Presentation of Jesus at the Temple or Forty Martyrs of Sebaste falls on that day, in which case certain foods are allowed).

Meatfare Week

The Saturday of this week is the first Saturday of the Dead observed during the Great Lenten season. The proper name in the typikon for the Sunday of this week is The Sunday of the Last Judgment, indicating the theme of the Gospel of the day (Matthew 25:31-46). The popular name of "Meatfare Sunday" comes from the fact that this is the last day on which the laity are permitted to eat meat until Pascha (Byzantine Rite monks and nuns never eat meat).

Cheesefare Week

During Cheesefare Week the eating of dairy products is permitted on every day (even Wednesday and Friday, which are normally observed as fast days throughout the year), though meat may no longer be eaten any day of the week. On the weekdays of this week, the first Lenten structural elements are introduced to the cycle of services on weekdays (the chanting of "Alleluia", the Prayer of Saint Ephrem, making prostrations, etc.).

Wednesday and Friday are the most lenten, but some lenten elements are also observed on Monday, Tuesday and Thursday. The office of Cheesefare Saturday celebrates the "Holy Ascetic Fathers".

Cheesefare Week is concluded on Cheesefare Sunday. The proper name for this Sunday is The Sunday of Forgiveness, both because of the Gospel theme for the day (Matthew 6:14-21) and because it is the day on which everyone asks forgiveness of their neighbor. The popular name of "Cheesefare Sunday" derives from the fact that it is the last day to eat dairy products before Pascha. On this Sunday, Eastern Christians identify with Adam and Eve, and forgive each other in order to obtain forgiveness from God, typically in a Forgiveness Vespers service that Sunday evening.

During Forgiveness Vespers (on Sunday evening) the hangings and vestments in the church are changed to somber Lenten colours to reflect a penitential mood. At the end of the service comes the "Ceremony of Mutual Forgiveness" during which all of the people one by one ask forgiveness of one another, that the Great Fast may begin in a spirit of peace.

The Great Forty Days

The forty days of Great Lent last from Clean Monday until the Friday of the Sixth Week. Each of the Sundays of Great Lent has its own special commemoration, though these are not necessarily repeated during the preceding week. An exception is the Week of the Cross (the Fourth Week), during which the theme of the preceding Sunday—the Veneration of the Cross—is repeated throughout the week. The themes introduced in the Pre-Lenten period continue to be developed throughout the forty days.

Clean Week

The first week of Great Lent starting on Clean Monday, the first day of Great Lent. The name "Clean Week" refers to the spiritual cleansing each of the faithful is encouraged to undergo through fasting, prayer, repentance, reception of the Holy Mysteries and begging forgiveness of his neighbor. It is also traditionally a time for spring cleaning so that one's outward surroundings matches his inward disposition.

Throughout this week fasting is most strict. Those who have the strength are encouraged to fast completely, eating only on Wednesday and Friday evenings, after the Presanctified Liturgy. Those who are unable to keep such a strict fast are encouraged to eat only a little, and then only xerophagy (see Prodigal Son) once a day. On Monday, no food should be eaten at all and only uncooked food on Tuesday and Thursday. Meals are served on Saturday and Sunday, but these are fasting meals at which meat, dairy products and fish are forbidden.

At Great Compline during the first four days of the Fast (Monday through Thursday) the Great Canon of St. Andrew of Crete is divided into four parts and one part is chanted each night (for further information about the Great Canon, see Fifth Week, below).

The First Saturday is called "St. Theodore Saturday" in honor of St. Theodore the Recruit, a 4th-century martyr. At the end of the Presanctified Liturgy on Friday (since, liturgically, the day begins at sunset) a special canon to St. Theodore, composed by St. John of Damascus, is chanted. Then the priest blesses kolyva (boiled wheat with honey and raisins) which is distributed to the faithful in commemoration of the following miracle worked by St. Theodore on the First Saturday of Great Lent.

Fifty years after the death of St Theodore, the emperor Julian the Apostate (361-363), as a part of his general policy of persecution of Christians, commanded the governor of Constantinople during the first week of Great Lent to sprinkle all the food provisions in the marketplaces with the blood offered to pagan idols, knowing that the people would be hungry after the strict fasting of the first week. St Theodore appeared in a dream to Archbishop Eudoxius, ordering him to inform all the Christians that no one should buy anything at the marketplaces, but rather to eat cooked wheat with honey (kolyva).

The First Sunday of Great Lent is the Feast of Orthodoxy, which commemorates the restoration of the veneration of icons after the Iconoclast controversy, which is considered to be the triumph of the Church over the last of the great heresies which troubled her (all later heresies being simply a rehashing of earlier ones). Before the Divine Liturgy on this day, a special service, known as the "Triumph of Orthodoxy" is held in cathedrals and major monasteries, at which the synodicon (containing anathemas against various heresies, and encomia of those who have held fast to the Christian faith) is proclaimed.

The theme of the day is the victory of the True Faith over heresy. "This is the victory that overcomes the world, our faith" (1 John 5:4). Also, the icons of the saints bear witness that man, "created in the image and likeness of God" (Genesis 1:26), may become holy and godlike through the purification of himself as God's living image.

The First Sunday of Great Lent originally commemorated the Prophets such as Moses, Aaron, and Samuel. The Liturgy's Prokeimenon and alleluia verses as well as the Epistle (Hebrews 11:24-26,32-40) and Gospel (John 1:43-51) readings appointed for the day continue to reflect this older usage.

Second Week

The Second Sunday of Great Lent commemorates St. Gregory Palamas, the great defender of the Church's doctrine of Hesychasm against its attack by Barlaam of Calabria. The Epistle is Hebrews 1:10-14; 2:1-3 and the Gospel is Mark 2:1-12

Throughout this week, and until the Sixth Friday in Lent, one meal may be taken a day with xerophagy. Until the Sixth Saturday in Lent, Saturday and Sunday fasting remains the same as in the First Week.

Third Week

The Veneration of the Cross is celebrated on the third Sunday. The veneration comes on this day because it is the midpoint of the forty days. The services for this day are similar to those on the Great Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross (September 14). During the All-Night Vigil the priest brings the cross out into the center of the church, where it is venerated by the clergy and faithful. It remains in the center of the church through Friday of the week following (the Fourth Week of Great Lent).[9]

The Epistle is Hebrews 4:14-5:6 and the Gospel is Mark 8:34-9:1.

Fourth Week

This week is celebrated as a sort of afterfeast of the Veneration of the Cross, during which some of the hymns from the previous Sunday are repeated each day. On Monday and Wednesday of the Fourth Week, a Veneration of the Cross takes place at the First Hour (repeating a portion of the service from the All-Night Vigil of the previous Sunday). On Friday of that week, the veneration takes place after the Ninth Hour, after which the cross is solemnly returned to the sanctuary by the priest and deacon.

The Sunday which ends the fourth week is dedicated to St. John Climacus, whose work, The Ladder of Divine Ascent has been read throughout the Great Lenten Fast.

Fifth Week

On Thursday of the Fifth Week, the Great Canon of St. Andrew of Crete is chanted. This is the longest Canon of the church year, and during the course of its nine Odes, most every person mentioned in the Bible is called to mind and tied to the theme of repentance. In anticipation of the Canon, Vespers on Wednesday afternoon is longer than normal, with special stichera added in honor of the Great Canon. The Great Canon itself is recited during Matins for Thursday, which is usually celebrated by anticipation on Wednesday evening, so that more people can attend.

As a part of the Matins of the Great Canon, the Life of St. Mary of Egypt by St. Sophronius, Patriarch of Jerusalem (634 - 638) is read, for her example of repentance and overcoming temptation. On this day also is chanted the famous kontakion, "My soul, my soul, why sleepest thou..." by St. Romanos the Melodist. The next day (Thursday morning) a special Presanctified Liturgy is celebrated, and the fast is relaxed slightly (wine and oil are allowed) as consolation after the long service the night before.

Saturday of the Fifth Week is dedicated to the Theotokos (Mother of God), and is known as the "Saturday of the Akathist" because the Akathist to the Theotokos is chanted during Matins on that day (again, usually anticipated on Friday evening).

The Fifth Sunday is dedicated to St. Mary of Egypt, whose Life was read earlier in the week during the Great Canon. At the end of the Divine Liturgy many churches celebrate a "Blessing of Dried Fruit", in commemoration of St. Mary's profound asceticism.

Sixth Week

During the Sixth Week the Lenten services are served as they were during the second and third weeks.

Great Lent ends at Vespers on the evening of the Sixth Friday, and the Lenten cycle of Old Testament readings is brought to an end. (Genesis ends with the account of the burial of Joseph, who is a type of Christ.) At that same service, the celebration of Lazarus Saturday begins. The resurrection of Lazarus is understood as a foreshadowing of the Resurrection of Jesus, and many of the Resurrection hymns normally chanted on Sunday (and which will be replaced the next day with hymns for Palm Sunday) are chanted at Matins on the morning of Lazarus Saturday.

Palm Sunday differs from the previous Sundays in that it is one of the Great Feasts of the Orthodox Church. None of the normal Lenten material is chanted on Palm Sunday, and fish, wine and oil are permitted in the trapeza. The blessing of palms (or pussywillow) takes place at Matins on Sunday morning, and everyone stands holding palms and lit candles during the important moments of the service.

This is especially significant at the Great Entrance during the Divine Liturgy on Palm Sunday morning, since liturgically that entrance recreates the entry of Jesus into Jerusalem. The themes of Lazarus Saturday and Palm Sunday are tied together, and some of the same hymns (including one of the apolytikia) are chanted on both days. The Holy Week services begin on the night of Palm Sunday, and the liturgical colours are changed from the festive hues of Lazarus Saturday and Palm Sunday back to somber Lenten colours.

Holy Week

Although technically, Holy Week is separate from Great Lent, its services mirror those of Great Lent and are contained in the same book, the Lenten Triodion. Whereas, during Great Lent each week has its own theme, during Holy Week each day has its own theme, again based upon the Gospel readings for the day:

- Holy and Great Monday—Joseph the all-comely as a type of Christ, and the account of The Fig Tree (Matthew 21:18-22)

- Holy and Great Tuesday—the Parable of the Ten Virgins (Matthew 25:1-13)

- Holy and Great Wednesday—The anointing of Jesus at Bethany (Matthew 26:6-16)

Note that for the previous three days, one meal a day is taken a day with xerophagy.

- Holy and Great Thursday—The Mystical Supper

One meal may be eaten on this day with wine and oil.

- Holy and Great Friday—The Passion (Matthew 27:62-66)

No food is to be eaten on this day.

- Holy and Great Saturday—The Burial of Jesus and the Harrowing of Hell (Matthew 28:1-20)

One meal may be eaten with xerophagy.

During Holy Week, the order of services is often brought forward by several hours: Matins being celebrated by anticipation the evening before, and Vespers in the morning. This "reversal" is not something mandated by the typicon but has developed out of practical necessity. Since some of the most important readings and liturgical actions take place at Matins, it is celebrated in the evening (rather than early in the morning before dawn, as is usual for Matins) so that more people can attend.

Since during Holy Week Vespers is usually joined to either the Presanctified Liturgy or the Divine Liturgy, and since the faithful must observe a total fast from all food and drink before receiving Holy Communion, it is celebrated in the morning. Vespers on Good Friday is an exception to this, usually being celebrated in late morning or in the afternoon.

The Matins services for Holy Monday through Thursday are referred to as "Bridegroom Prayer" because the troparion of the day and the exapostilarion (the hymn that concludes the Canon) develop the theme of "Christ the Bridegroom". Thursday has its own troparion, but uses the same exapostilarion. The icon often displayed on these days depicts Jesus and is referred to as "the Bridegroom" because the crown of thorns and the robe of mockery are parallel to the crown and robe worn by a bridegroom on his wedding day.

This icon is often confused with the visually similar icon of Christ as the Man of Sorrows, which shows Him post-Crucifixion in the same pose but lacking the rod and robe, dead, showing the marks of the nails in his Hands and the spear wound in His side. Incidentally, Thursday has its own icon showing either the Mystical Supper or the Washing of Feet, or both. The Passion of Christ is seen as the wedding of the Saviour with his bride, the Church.

Holy Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday

The first three days of Holy Week (Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday), the services all follow the same pattern and are nearly identical to the order followed on weekdays during the Great Forty Days; however, the number of Kathismata (sections from the Psalter) is reduced and the Old Testament readings are taken from different books. The Presanctified Liturgy is celebrated on each of the first three days, and there is a Gospel reading at each one (during the Forty Days there was no Gospel reading unless it was a feast day). There is also a Gospel reading at Matins on each day and the Canon chanted at Matins is much shorter, consisting of only three or four odes rather than the usual nine.

In addition to the Gospel readings at Matins and Vespers, there is a reading of all four Gospels which takes place during the Little Hours (Third Hour, Sixth Hour and Ninth Hour) on these first three days. Each Gospel is read in its entirety and in order, beginning with Matthew 1:1, and continuing through John 13:30 (the rest of the Gospel of John will be read during the remainder of Holy Week). The Gospels are divided up into nine sections with one section being read by the priest at each of the Little Hours.

The Prayer of Saint Ephrem is said for the last time at the end of the Presanctified Liturgy on Holy and Great Wednesday. From this moment on, there will be no more prostrations made in the church (aside from those made before the epitaphios) until Vespers on the afternoon of Pentecost.

In some churches, the Holy Mystery (Sacrament) of Unction is celebrated on Holy and Great Wednesday, in commemoration of the anointing of Jesus' feet in preparation for his burial (Matthew 26:6-13).

The remaining three days of Holy Week retain a smaller degree of Lenten character, but each has elements that are unique to it.

Holy (Maundy) Thursday

Holy and Great Thursday is a more festive day than the others of Holy Week in that it celebrates the institution of the Eucharist. The hangings in the church and the vestments of the clergy are changed from dark Lenten hues to more festive colours (red, in the Russian tradition).

Whereas the Divine Liturgy is forbidden on other Lenten weekdays, the Divine Liturgy of St. Basil (combined with Vespers) is celebrated on this day. Many of the standard hymns of the Liturgy are replaced with the Troparion of Great Thursday. In some churches, the Holy Table (altar) is covered with a simple white linen cloth, in commemoration of the Mystical Supper (Last Supper).

During this Divine Liturgy, the reserved Mysteries are renewed (a new Lamb being consecrated, and the old Body and Blood of Christ being consumed by the deacon after the Liturgy). Also, when the supply of Chrism runs low, it is at this Liturgy that the heads of the autocephalous churches will Sanctify new Chrism, the preparation of which would have been begun during the All-Night Vigil on Palm Sunday.

After the Liturgy, a meal is served. The rule of fasting is lessened somewhat, and the faithful are allowed to partake of wine in moderation during the meal and use oil in the cooking.

That night, the hangings and vestments in the church are changed to black, and Matins for Great and Holy Friday is celebrated.

Good Friday

Holy and Great Friday is observed as a strict fast day, on which the faithful who are physically able to should not eat anything at all. Some even fast from water, at least until after the Vespers service that evening.

The Matins service, usually celebrated Thursday night, is officially entitled, "The Office of the Holy and Redeeming Passion of our Lord Jesus Christ".[10] It is commonly known as the "Matins of the Twelve Gospels", because interspersed throughout the service are twelve Gospel readings which recount the entire Passion of Christ from the Last Supper to the sealing of the tomb. Before the Sixth Gospel (Mark 15:16-32) which first mentions the Crucifixion, the priest carries a large cross into the center of the church, where it is set upright and all the faithful come forward to venerate it. The cross has attached to it a large icon of the soma (the crucified body of Christ).

At the beginning of each Gospel, the bell is rung according to the number of the Gospel (once for the first Gospel, two for the second, etc.). As each Gospel is read the faithful stand holding lighted candles, which are extinguished at the end of each reading. After the twelfth Gospel, the faithful do not extinguish their candles but leave them lit and carry the flame to their homes as a blessing. There, they will often use the flame to light the lampada in their icon corner.

On the morning of Great Friday, the Royal Hours are served. This is a solemn service of the Little Hours and Typica to which antiphons, and scripture readings have been added. Some of the fixed psalms which are standard to each of the Little Hours are replaced with psalms which are of particular significance to the Passion.

Vespers on Good Friday is usually celebrated after the Royal Hours service,[11] although in some monasteries it is served in the afternoon.[12] After the Little Entrance the Gospel reading is a concatenation of the four Evangelists' accounts of the Crucifixion and the Descent from the Cross. At the point during the reading which mentions Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, two clergymen approach the large cross in the center of the church, remove the soma, wrap it in a piece of white linen, and carry it into the sanctuary.

Later, during the Troparion, the clergy carry the epitaphios (a cloth icon symbolizing the winding sheet in which Jesus was prepared for burial) into the center of the church, where it is venerated by all the faithful. Special chants and prayers and chanted along with biblical readings and psalms chanted.

That night, the Matins of Lamentation is normally celebrated in the evening. At this service, special hymns and prayers are chanted. The Lamentations of Great and Holy Friday are the main chants of the service. The Lamentation Praises are chanted to very movingly beautiful ancient tones and words which reflect the lament of the Theotokos over her son Christ. The epitaphios is placed on a beautifully ornate and decorate catafalque or bier before the Lamentations representing the tomb of Christ.

The priest then sprinkles rosewater and fresh rose petals all over the tomb, the congregation, and the temple/church. A procession with the ornate tomb then takes place around the church and back into the church where it will be venerated by everyone. As more special prayers and chants are sung especially the chant: "The Noble Joseph..." as the service finishes.

Holy Saturday

Holy and Great Saturday (known also as the Great Sabbath, because on it Jesus "rested" from his labours on the Cross) combines elements of deep sorrow and exultant joy. This, like Good Friday is also a day of strict fasting, though a meal may be served after the Divine Liturgy at which wine (but not oil) may be used.

The Matins of Lamentation (usually celebrated on Friday evening) resembles the Byzantine Rite funeral service, in that its main component is the chanting of Psalm 118 (the longest Psalm in the Bible), each verse of which is interspersed with laudations (ainoi) of the dead Christ. The service takes place with the clergy and people gathered around the epitaphios in the center of the church. Everyone stands holding lighted candles during the psalm. Next are chanted the Evlogitaria of the Resurrection, hymns which are normally chanted only on Sundays.

This is the first liturgical mention of the impending Resurrection of Jesus. At the end of the Great Doxology the epitaphios is carried in procession around the outside of the church, as is the body at a priest's funeral, and then is brought back in. By local custom, the clergy may raise the epitaphios at the door so that all may pass under it as they enter in, symbolically entering into the death and resurrection of Jesus. The Gospel (Matthew 27:62-66) is not read at its usual place during Matins, but rather, following readings of the vision in Ezekiel of the dry bones returning to life and an Epistle, near the end of the service, in front of the epitaphios.

The next morning (Saturday), the Divine Liturgy of St. Basil is celebrated (combined with Vespers). At the beginning of the service, the hangings and vestments are still black. The service is much longer than usual, and includes 15 Old Testament readings recounting the history of salvation, including two canticles, the Song of Moses and the Song of the Three Holy Children, and showing types of the death and resurrection of Jesus.

Many parts of the liturgy which are normally performed in front of the Holy Doors are instead done in front of the epitaphios. Just before the Gospel reading, the hangings and vestments are changed to white, and the entire atmosphere of the service is transformed from sorrow to joy. In the Greek practice, the priest strews the entire church with fresh bay leaves, symbolizing Christ's victory over death. This service symbolizes the descent of Christ into Hades and the Harrowing of Hell.

Thus, according to Byzantine Rite theology, Jesus' salvific work on the Cross has been accomplished, and the righteous departed in the Bosom of Abraham have been released from their bondage; however, the Good News of the Resurrection has not yet been proclaimed to the living on earth, the celebration of which commences at midnight with Matins. For this reason, neither is the fast broken nor the Paschal greeting exchanged.

At the end of the Divine Liturgy, the priest blesses wine and bread which are distributed to the faithful. This is different from the Sacred Mysteries (Holy Communion) which were received earlier in the service. This bread and wine are simply blessed, not consecrated. They are a remnant of the ancient tradition of the church (still observed in some places) whereby the faithful did not leave the church after the service, but were each given a glass of wine, and some bread and dried fruit to give them strength for the vigil ahead. They would listen to the reading of the Acts of the Apostles, read in full, and await the beginning of the Paschal Vigil. However, this is not usually done nowadays.

The last liturgical service in the Lenten Triodion is the Midnight Office which forms the first part of the Paschal Vigil. During this service the Canon of Great Saturday is repeated, near the end of which, during the ninth ode, the priest and deacon take the epitaphios into the sanctuary through the Holy Doors and lay it on the Holy Table (altar), where it remains until the feast of the Ascension. After the concluding prayers and a dismissal, all of the lights and candles in the church are extinguished, and all wait in silence and darkness for the stroke of midnight, following which the Pentecostarion replaces the Lenten Triodion, commencing with the resurrection of Christ being proclaimed.

See also

- Lent

- Maslenitsa

- Easter

- Coptic Lent

- Nativity Fast

- Apostles' Fast

- Dormition Fast

- Sawma Rabba

- Fasting and abstinence in the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church

References

- ↑ Moroz, Vladimir (10 May 2016). "Лютерани східного обряду: такі є лише в Україні" (in uk). РІСУ - Релігійно-інформаційна служба України. https://risu.org.ua/ua/index/exclusive/kaleidoscope/63352/. "В українських лютеран, як і в ортодоксальних Церквах, напередодні Великодня є Великий Піст або Чотиридесятниця."

- ↑ Kallistos (Ware), Bishop; Mary, Mother (1977), "The Meaning of the Great Fast", The Lenten Triodion, South Canaan, PA: St. Tikhon's Seminary Press (published 2002), pp. 13 ff, ISBN 1-878997-51-3

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Concerning Fasting on Wednesday and Friday. Orthodox Christian Information Center. Accessed 2010-10-08.

- ↑ "The Fasting Rule of the Orthodox Church". http://www.abbamoses.com/fasting.html.

- ↑ "The Fasting Rule of the Church". abbamoses.com. http://www.abbamoses.com/fasting.html.

- ↑ Menzel, Konstantinos (14 April 2014). "Abstaining From Sex Is Part of Fasting" (in English). Greek Reporter. https://greekreporter.com/2014/04/14/abstaining-from-sex-is-part-of-fasting/.

- ↑ Archbishop Job Getcha: The Typikon Decoded: An Explanation of Byzantine Liturgical Practice. St Vladimir's Seminary Press: Yonkers, New York. ISBN 978-088141-412-7

- ↑ Sokolof, Archpriest D. (1917), "Moveable Feasts and Fasts", A Manual of the Orthodox Church's Divine Services, Jordanville, NY: Printshop of St. Job of Pochaev (published 2001), p. 98

- ↑ Sunday of the Cross Orthodox synaxarion

- ↑ Bishop Kallistos, op. cit., p. 565

- ↑ "Μεγάλη Παρασκευή: LIVE η λειτουργία του Επιτάφιου" (in el). News24/7. 17 April 2020. https://www.news247.gr/koinonia/megali-paraskeyi-i-apokathilosi-toy-estayromenoy-kai-o-epitafios.7625284.html. "Το πρωί της Μεγάλης Παρασκευής γίνεται ο στολισμός του Επιταφίου στις εκκλησίες. Αρχικά ψάλλονται οι Μεγάλες Ώρες, που περιέχουν ψαλμούς, τροπάρια, Αποστόλους, Ευαγγέλια και Ευχές."

- ↑ "Παρασκευή μεγάλη [Good Friday]". Great Greek Encyclopedia. ΙΘ΄. Athens: Phoenix. p. 664.

External links

- Resources for Great Lent

- Sundays of Great Lent

- The Great Lent & The Holy Paskha—Coptic articles and hymns at http://St-Takla.org

- Great Lent, Holy Week, and Pascha in the Greek Orthodox Church

- Great Lent: History, Significance, Meaning

- Great Lent and Holy Pascha

- A Homily on Fasting and Dispassion by St. Theodore the Studite, to be read at the beginning of Great Lent

- The Origins of Lent A study of the early historical development of the fast

|