Religion:Annapurna Upanishad

| Annapurna Upanishad | |

|---|---|

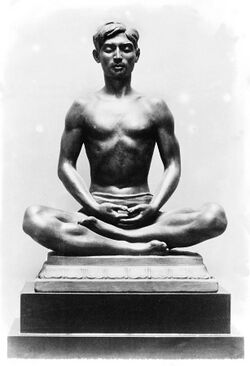

The Upanishad discusses meditation and spiritual liberation | |

| Devanagari | अन्नपूर्णा |

| IAST | Annapūrṇā |

| Title means | Abundance of food |

| Type | Samanya (general)[1] |

| Linked Veda | Atharvaveda[1] |

| Chapters | 5[2] |

| Verses | 337[2] |

| Philosophy | Vedanta[1] |

The Annapurna Upanishad (Sanskrit: अन्नपूर्णा उपनिषद्, IAST: Annapūrṇā Upaniṣad) is a Sanskrit text and one of the minor Upanishads of Hinduism.[3] It is classified as a Samanya Upanishads and attached to the Atharvaveda.[1]

The text is structured into five chapters, as a discourse between yogin Nidagha and Vedic sage Ribhu.[4][5] The first chapter presents a series of questions such as "Who am I? How did the universe come about? what is the meaning of birth, death and life? what is freedom and liberation?"[6] The text then discusses its answers, after attributing the knowledge to goddess Annapurna.[5]

The text is notable for describing five types of delusions, asserting the Advaita Vedanta doctrine of non-duality and oneness of all souls and the metaphysical Brahman, defining spiritual liberation as being unattached to anything and freedom from inner clingings. The text describes Jivanmukti – achieving freedom in this life, and the characteristics of those who reach self-knowledge.[7][6][8]

History

The author and the century in which Annapurna Upanishad was composed is unknown. Manuscripts of this text are also found titled as Annapurnopanisad.[7][9] This Upanishad is listed at number 70 in the Telugu language anthology of 108 Upanishads of the Muktika canon, narrated by Rama to Hanuman.[10]

Contents

The text consists of five chapters, with a cumulative total of 337 verses.[11][6]

Silence as teacher

The text opens with yogin Nidagha meeting the one who knows Brahman, the Vedic sage Ribhu, paying respects and then asking, "teach me the truth about Atman (soul, Self)". Ribhu begins his answer, in verses 1 to 12, by disclosing the source of his knowledge, which he attributes to goddess Annapurna, calling her the ruler of the world, the goddess of fulfillment, desire and humanity. Ribhu states that he reached the goddess using the prayers developed by the group of female monks. After many days of prayers, states Ribhu, the goddess Annapurna appeared, smiling. She asked him what boon he wanted, and Ribhu replied, "I want to know the truth about soul". The goddess just vanished, giving him silence, and the introspection in this silence, states Ribhu, revealed him the Self-knowledge.[12][13]

But the lover of the inner Self,

though operating through the organs of action,

is unaffected by joy and sorrow,

he is said to be in Samahita (harmony).

He who, as a matter of course and not through fear,

beholds all beings as one’s own Self,

and others’ possessions as clods of earth,

alone sees aright.

—Annapurna Upanishad 1.37–38

Translated by AGK Warrier[14][13][15]

Five delusions

The Annapurna Upanishad asserts, in verses 1.13 to 1.15, that delusions are of five kinds.[16][17][18] The first is believing in the distinction between Jiva (living being) and god as if they have different forms.[16] The second delusion, asserts the text, is equating agency (actor-capacity, person-ego) as Self. Assuming Jiva as equivalent and permanently attached to body is the third delusion, states the text.[16] The fourth delusion is to assume the cause of the universe to be changing, and not constant.[16] The fifth delusion, asserts the Upanishad, is to presume the unchanging Reality in the universe to be different from the cause of the universe. These five delusive premises, asserts the text, prevents the understanding of Self.[19][20]

Soul is same in every being

Verses 1.22 to 1.39 of the text discuss the soul and one's true identity as that "which is the indestructible, infinite, Spirit, the Self of everything, integral, replete, abundant and partless", translates Warrier.[21][22] Self-knowledge is born of awareness, asserts the text, and the soul is Brahmanic bliss, a state of inner calm no matter what, one of contemplation, of tranquil aloneness, of perpetual quiescence.[21] It is the mind that craves and clings for objects and sensory impulses, leading to bondage to the object and whoever controls the object, states the text.[21] This causes suffering and the lack of true bliss. The awareness of this inner process, the attenuation of such mind, and the refocussed concentration on the soul leads to "inner cool" and "self love".[23][22]

The Upanishad states that just like one walks through an active crowd in a market, aware only of one's loved ones and goals, and unaware of those unrelated, in the same way, the one with self-knowledge is like a village in the forest of life.[23][22]

A Self-knower is not swung either by sorrow or by joy, he beholds all living beings as his own self, he fears no one, and other people's possessions means nothing to him.[24][15] They are inwardly withdrawn, and to them the city, the country side and the forest are spiritually equivalent.[25] They have an inner thirst, asserts the Upanishad, and the world is forever interesting to those with self-knowledge.[25][13]

Who am I?

The Annapurna Upanishad, through sage Ribhu in verse 1.40, asks the yogin to introspect, "who am I? how is the universe brought about? what is it? how does birth and death happen?"[26][27][28] It is these sort of questions, asserts the text, that leads one to investigate one's real nature, cure meaningless feverishness of mind, and comprehend the temporariness of life.[29] Renounce all the cravings and objects, obliterate all clingings, states the text in verses 1.44 to 1.57, and assimilate the answers that remain. Mind is the source of bondage, mind liquidates mind, and mind helps attain freedom, asserts the text.[29][30] The one with self-knowledge is even-minded, states verse 1.54.[31][32]

Jivanmukti

Chapter 2 of the Upanishad describes the state of Jivanmukti, that is "spiritual liberation or freedom in the current life".[33][34][35] It is a state, asserts the text, of non-attachment, neither of inactivity, nor of clinging to activities.[33][35] Freedom is the inner sense of being active when one wants to and without craving for the fruits thereof, and it is the inner sense of not being active when one doesn't.[33][36] His occupation is neither doing nor non-doing, his true occupation is Self-delight.[33] The truly free doesn't want anything or anyone, he is "steadfast, blissful, polished, simple, sweet, without self-pity", and he works and lives because he wants to, without "craving for what is yet to be, or banking on the present, or remembering the past", is a "Jivanmukta (liberated in life)" states verses 2.28–29.[33][34]

Though standing, walking, touching, smelling,

the liberated one, devoid of all clingings,

gets rid of servitude to desires and dualities;

he is at peace.

A shoreless ocean of excellences,

he crosses the sea of sufferings,

because he keeps to this vision,

even in the midst of vexed activities.

He reaches this state because "all the world is his Self alone", self-realization is the plenitude that is everywhere in the world, all is one supreme sky, devoid of all duality, the free is being you, yourself, the Self and nothing else, states verse 2.39.[33][34] The best renunciation, asserts the text, is through the virtue of knowledge to the state of Aloneness, as it reflects the state of pure universal Being where all is the manifestation of one Atman alone.[39]

Yoga, Siddhi and self-knowledge

Chapter 3 of the text describes the example of sage Mandavya who with yoga as the means to withdraw the self from the senses, reached self-knowledge.[40][41][8] This description, states Andrew Fort, is representative of Yogic Advaita themes.[8] Chapter 4 states that those who seek and know the Self have no interest in supernatural Siddhi powers, they are more childlike because they enjoy the childlike inner freedom.[42][43][44] In verse 39 the Upanishad states "Without sound reasoning it is impossible to conquer the mind". The verses 4.40 to 4.92 of the text describe the state of a liberated person, as one who has achieved tranquility in his soul and has destroyed the craving and clinging processes of the mind.[45][46]

The one with free spirit

The text, in chapter 5,[note 1] continues its description of the liberated person with self-knowledge and free spirit.[48][49][47]

The one with free spirit, asserts the text, knows his soul to be of the "nature of light, of right knowledge", he is fearless, cannot be subjugated nor depressed, he does not care about after life, is never attached to anything.[50] He is a silent man, yet full of activity, quiet but delightful in his self, asserts the text. He knows, states the text, that "I am self that is the spirit, I am all, all is me, Brahman is the world, the world is Brahman, I am neither the cause nor the effect, vast and never finite".[51][52] He knows, "I am That", states verse 5.74 of the Annapurna Upanishad.[51][53]

See also

Notes

- ↑ According to Fort, the ideas in chapter 5 of Annapurna are also found in the texts Yoga Vasistha and Jivanmuktiviveka.[47]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Tinoco 1996, p. 87.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Hattangadi 2000, pp. 1–23.

- ↑ Mahadevan 1975, pp. 235–236.

- ↑ Warrier 1967, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Mahadevan 1975, pp. 174–175.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Warrier 1967, pp. 22–69.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Vedic Literature, Volume 1, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Sanskrit Manuscripts, p. PA281, at Google Books, Government of Tamil Nadu, Madras, India, pages 281–282

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Fort 1998, pp. 120–121.

- ↑ Ayyangar 1941, p. 28.

- ↑ Deussen 1997, pp. 556–557.

- ↑ Hattangadi 2000, pp. 1–23, note some verses are of unequal lengths and numbered slightly differently between manuscripts.

- ↑ Warrier 1967, pp. 25–26.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Hattangadi 2000, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Warrier 1967, p. 25-26.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Ayyangar 1941, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Warrier 1967, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Hattangadi 2000, p. 2, 1.12–1.15 note verses are numbered slightly differently by this source, with two verses labelled as 12.

- ↑ Ayyangar 1941, pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Warrier 1967, p. 23-24.

- ↑ Hattangadi 2000, p. 2.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Warrier 1967, pp. 24–27.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Hattangadi 2000, p. 3.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Warrier 1967, pp. 26–28.

- ↑ Warrier 1967, p. 27-29.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Warrier 1967, pp. 27–29.

- ↑ Warrier 1967, pp. 29–30.

- ↑ Hattangadi 2000, p. 4.

- ↑ Ayyangar 1941, p. 36.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Warrier 1967, pp. 29–32.

- ↑ Hattangadi 2000, pp. 4–5, this theme reappears in chapter 4, verses 4.11–4.24.

- ↑ Warrier 1967, p. 29-32.

- ↑ Hattangadi 2000, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 33.5 Warrier 1967, pp. 33–40.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Hattangadi 2000, pp. 5–7.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Fort 1998, p. 120.

- ↑ Ayyangar 1941, pp. 39–42.

- ↑ Warrier 1967, p. 57-58.

- ↑ Hattangadi 2000, p. 19.

- ↑ Ayyangar 1941, pp. 44–48.

- ↑ Warrier 1967, pp. 40–44.

- ↑ Hattangadi 2000, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Warrier 1967, pp. 44–49.

- ↑ Hattangadi 2000, pp. 10–12, verses 4.1–3 and 4.37–38.

- ↑ Ayyangar 1941, pp. 49–54.

- ↑ Warrier 1967, pp. 47–59.

- ↑ Hattangadi 2000, pp. 12–15.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Fort 1998, p. 121.

- ↑ Warrier 1967, pp. 59–69.

- ↑ Hattangadi 2000, pp. 15–23.

- ↑ Ayyangar 1941, pp. 67–71.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Warrier 1967, p. 59-69.

- ↑ Hattangadi 2000, pp. 15–17, 5.5–21.

- ↑ Hattangadi 2000, p. 20, verse 5.74.

Bibliography

- Ayyangar, T. R. Srinivasa (1941). The Samanya Vedanta Upanisads. Jain Publishing (Reprint 2007). ISBN 978-0895819833. OCLC 27193914.

- Deussen, Paul (1997). Sixty Upanishads of the Veda. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1467-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=XYepeIGUY0gC&pg=PA556.

- Fort, Andrew O. (1998). Jivanmukti in Transformation: Embodied Liberation in Advaita and Neo-Vedanta. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-3904-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=iG_J96ALMZYC.

- Hattangadi, Sunder (2000). "अन्नपूर्णोपनिषत् (Annapurna Upanishad)" (in sa). http://sanskritdocuments.org/doc_upanishhat/annapurnaupan.pdf.

- Mahadevan, T. M. P. (1975). Upaniṣads: Selections from 108 Upaniṣads. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1611-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=yluXuM5NuUIC&pg=PA234.

- AM Sastri, ed (1921) (in sa). The Samanya Vedanta Upanishads with the commentary of Sri Upanishad-Brahma-Yogin. Adyar Library (Reprinted 1970).

- Tinoco, Carlos Alberto (1996). Upanishads. IBRASA. ISBN 978-85-348-0040-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=7xoNEM63hZEC&pg=PA88.

- Warrier, AG Krishna (1967). Sāmanya Vedānta Upaniṣads. Adyar Library and Research Center. ISBN 978-8185141077. OCLC 29564526.