Biology:Azendohsaurus

| Azendohsaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

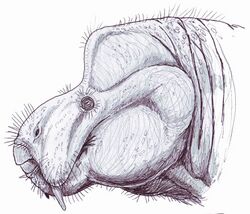

| An Azendohsaurus tooth, the paratype specimen (MNHN-ALM 424) of A. laaroussii | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Archosauromorpha |

| Clade: | Crocopoda |

| Clade: | †Allokotosauria |

| Family: | †Azendohsauridae |

| Genus: | †Azendohsaurus Dutuit, 1972 |

| Type species | |

| †Azendohsaurus laaroussii Dutuit, 1972

| |

| Species | |

| |

Azendohsaurus is an extinct genus of herbivorous archosauromorph reptile from roughly the late Middle to early Late Triassic Period of Morocco and Madagascar . The type species, Azendohsaurus laaroussii, was described and named by Jean-Michel Dutuit in 1972 based on partial jaw fragments and some teeth from Morocco. A second species from Madagascar, A. madagaskarensis, was first described in 2010 by John J. Flynn and colleagues from a multitude of specimens representing almost the entire skeleton. The generic name "Azendoh lizard" is for the village of Azendoh, a local village near where it was first discovered in the Atlas Mountains. It was a bulky quadruped that unlike other early archosauromorphs had a relatively short tail and robust limbs that were held in an odd mix of sprawled hind limbs and raised forelimbs. It had a long neck and a proportionately small head with remarkably sauropod-like jaws and teeth.

Azendohsaurus used to be classified as a herbivorous dinosaur, at first as an ornithischian but more often as a "prosauropod" sauropodomorph. This was based only on its jaws and teeth, which share derived features typically found in herbivorous dinosaurs. The complete skeletal material from Madagascar, however, revealed more basal characteristics ancestral to Archosauromorpha and that Azendohsaurus was not a dinosaur at all. Instead, Azendohsaurus was actually a more primitive archosauromorph that had convergently evolved many features of the jaws and skeleton shared with the later giant sauropod dinosaurs. It was found to be a member of a newly recognised group of specialised, mostly herbivorous archosauromorphs that was named the Allokotosauria. It is also the namesake and typifier of its own family of allokotosaurs, the Azendohsauridae; initially the only member, the family now includes other similar allokotosaurs, such as the larger, horned azendohsaurid Shringasaurus from India .

Several other groups of archosauromorphs also adapted to herbivory in the Triassic, sometimes with dinosaur-like teeth that also caused confusion in their classification. Azendohsaurus is notable, however, for also convergently evolving a similar body shape to sauropodomorphs in addition to its jaws and teeth. Azendohsaurus and sauropodomorphs likely independently evolved to fill a similar ecological niche as long-necked, relatively high browsing herbivores in their environments. However, Azendohsaurus predates the large Late Triassic sauropodomorphs it resembles by several million years, and did not evolve similar body plans under the same environmental conditions. It may then have been one of the first herbivores to fill the high-browsing role that only large sauropodomorphs were thought to occupy during the Triassic, expanding the known ecological diversity of herbivorous archosauromorphs outside of dinosaurs in the Triassic Period. Azendohsaurus is also significant as it may be one of the earliest endothermic archosauromorphs known, and suggests that a warm-blooded metabolism was ancestral to the later archosaurs, including the dinosaurs.

Description

Azendohsaurus was a stocky mid-sized reptile estimated to be roughly 2–3 metres (6.6–9.8 ft) long. It had a small, box-shaped head with a short snout on a long neck that was raised above the shoulders. The body was broad, with a barrel-shaped chest and shoulders much taller than the hips, together with an unusually short tail. Its posture was semi-sprawled, with sprawling hind limbs and slightly elevated forelimbs. The limbs themselves are relatively short and particularly robust, with digits that are shorter and stouter compared to other early archosauromorphs, each with notably large, curved claws on all four feet. Superficially its appearance is comparable to that of sauropodomorph dinosaurs, along with various details of its skeleton, suggesting Azendohsaurus converged on similar traits for a relatively high-browsing, herbivorous lifestyle. A. laaroussii is poorly known compared to A. madagaskarensis, and the two species are only known to differ in minor details of the jaw bones and teeth. Additional skeletal material of A. laaroussii has been reported from the type locality of the original skull fragments, but have yet to be formally described as of 2015.[1][2]

Skull

The skull of A. madagaskarensis is almost completely known, and is robustly built with a short and boxy shape and a deep snout. The premaxillae are gently curved at the front of the upper jaw, forming a blunt, round snout tip, while the lower jaws have a deep, down-turned tip like those of sauropods. The bony nostrils are fused into a single (confluent) opening that faces forwards at the front of the snout, similar to those of rhynchosaurs.[1]

The skull has a number of traits convergent with sauropodomorphs, including the downward curving dentary, a robust dorsal process of the maxilla, and several features of the teeth. The process on the maxilla usually indicates the presence of an antorbital fenestra in archosauriforms, but in Azendohsaurus this space is occupied by the lacrimal bone in front of the eyes. This is a unique arrangement unknown in other Triassic archosauromorphs, except for the related Shringasaurus.[3] The orbits are almost entirely occupied by the large sclerotic rings, suggesting large eyes. The lower temporal fenestra is open at the bottom, separating the jugal and the quadratojugal bones (a primitive trait for archosauromorphs). Also like other early archosauromorphs, Azendohsaurus has a small (3–5 mm across) parietal foramen ("third eye") on the roof of the skull.[1]

The lower jaw is especially convergent with those of sauropodomorphs, with an articular joint where the jaw hinges positioned below the level of the tooth row and downward curving dentaries, as well as the similarly shaped teeth. These features are variously found in other herbivorous Triassic archosauromorphs, but this combination is only known in Azendohsaurus and sauropodomorphs.[1]

The teeth are all roughly leaf-shaped (lanceolate) with expanded crowns and bulbous bases that are fused to the jaw bones (ankylothecodont).[1] However, the upper and lower teeth are distinctly heterodont, and can be readily distinguished from each other. The upper teeth are relatively short and broad at their base, with 4–6 denticles on each surface, similar to ornithischians; the lower teeth are almost twice as tall and have twice as many denticles, more closely resembling the teeth of sauropodomorphs.[4] The four premaxillary teeth are the longest teeth in the upper jaw, and are more recurved back in shape than the rest.[1]

The palate is unusually covered in numerous fully developed palatal teeth, with up to four sets on the pterygoid and additional rows on the palatine and vomers. Mature Azendohsaurus madagaskarensis have at least 44 pairs of palatal teeth, in addition to the 4 teeth in each premaxilla and 11–13 in the maxilla each, along with a maximum of 17 teeth in the dentary. Palatal teeth are not uncommon in herbivorous reptiles, but in Azendohsaurus they are almost identical in shape to those along the jaw margins, but a bit stouter. Other archosauromorphs with palatal teeth have a much simpler palatal dentition of small, domed teeth.[1] Teraterpeton is the only other archosauromorph with similarly well developed palatal teeth.[5]

The only described material of A. laaroussii are dentaries, maxillae, a premaxilla and several teeth. They broadly resemble A. madagaskarensis in general form but with a few distinguishing differences. The tooth count of A. laaroussii is higher, with 15–16 teeth in the maxilla compared to the 11–13 of A. madagaskarensis. The teeth of A. laaroussii are also taller than those of A. madagaskarensis and have more closely packed denticles. Further distinguishing the two species is the presence of a prominent keel on the inside surface of the maxilla. This keel runs the whole length of the maxilla in A. laaroussii, but is only found along the back half of it in A. madagaskarensis. Any other possible differences between the two species cannot be determined without rest of the skull and skeleton.[1]

Skeleton

All the known post-cranial information for the skeleton of Azendohsaurus comes from A. madagaskarensis. Much of the vertebral column is known in Azendohsaurus, and although incomplete, it is estimated to have 24 presacral vertebrae (including the atlas and axis). The sacrum of the hips has only two vertebrae, and the full number of caudal vertebrae in the tail is unknown, but it is estimated to be only around 45–55 (low for an archosaur).[2]

The cervical vertebrae change shape down the neck, beginning as characteristically elongated with long and low neural spines, and getting progressively shorter in length towards the base of the neck, but with increasingly taller and narrower neural spines. This shortening is seen in the necks of other allokotosaurs like Trilophosaurus, but is not found in other long-necked archosauromorphs (e.g. the middle cervicals are the longest in tanystropheids). The neck would have been held raised up above the body, indicated by the inclined angle of the zygapophyses that connect each vertebra, as well as the front zygapophyses of each vertebra being higher than those at the back. The neck was also likely held in a gentle arc, based on an articulated set of cervicals in this position.[2]

The dorsal vertebrae of the back generally resemble the last cervicals, with tall, vertical neural spines. These vertebrae also decrease in length down the back, but less dramatically than in the neck. The last dorsal is unique, however, as it has a neural spine angled forward. Of the two sacrals, the first vertebra is larger and more robust, with a tall neural spines over its rear half. Both sacrals have large ribs completely fused to the vertebrae that articulate with the ilia (see below).[2]

The caudal vertebrae resemble the other vertebrae, but with backward inclined neural spines. The length of the caudals and the height of the neural spines gradually decreases down the tail, unlike some other archosauromorphs where the vertebrae elongate towards the tip. This implies that the tail was short and not tapering, but the very tip of the tail is unknown. They consistently have chevron facets from the 3rd or 4th vertebrae down to the last known caudals in the series.[2]

The cervical ribs are long and thin, becoming more robust and tapered as they move down the neck. Some of the cervical ribs from bottom half of the neck have a slight facet on the inside surface at their tips that may have held the tip of the preceding rib, forming a rigid cervical rib series (also suggested for the long necked Tanystropheus) that would stiffen the neck. The trunk ribs are long and curve outwards, indicating Azendohsaurus had a broad and deep barrel-shaped chest. The length and curvature of the ribs decreases down the spine, and the last rib is short, fused completely to the final dorsal vertebra, and points directly outwards to the sides. Only a single set of gastralia is known for Azendohsaurus, and their very delicate build and rarity compared to other bones suggests that it did not have a well developed basket of gastralia under the belly like some other archosauromorphs (e.g. Proterosuchus).[2]

Limbs and girdles

The forelimbs and shoulders (pectoral girdle) of Azendohsaurus are well developed and robust. The scapula (shoulder blade) is long, about twice as tall as it is wide, matching the length and curvature of the ribs to accommodate the deep chest. The blade is concave on each side with a slightly expanded tip that is pointed at the back. The interclavicle is large and robust, and shares with Trilophosaurus and some rhynchosaurs a long "paddle-like" posterior process that is flattened and expanded towards the tip. It also has a unique forward-pointing process, a feature it shares only with Protorosaurus and some early diapsids (most other archosauromorphs have a notch instead).[2]

The coracoids are large and rounded, articulating with the scapula to form the glenoid (shoulder socket). The glenoid faces laterally, typical of sprawling reptiles, however, the scapular portion is directed slightly backwards, which could indicate the humerus was held in a more raised posture. The humerus itself is large and broadly expanded at both ends, leaving a relatively narrow "waisted" mid-shaft, with a very well developed deltopectoral crest. The radius is similarly stocky with slightly expanded ends, while the ulna is greatly expanded at both ends, though to a lesser extent distally.[2]

The hips (pelvic girdle) are not as deep as the shoulders, with the three hip bones being roughly equal in size. The ilium is tall and curved along the top surface, with a short rounded process at the front and a longer tapering process behind it. The pubis points down and slightly forwards, and only has a slightly thickened expansion (boot) at the tip. The ischium is relatively short, shorter than the ilium, and roughly triangular in shape with straight edges and a rounded rear tip. The articulation surfaces between each ischia are unusually expanded compared to other archosauromorphs. All three contribute to forming a deep, rounded acetabulum (hip socket). Unlike the open socket of dinosaurs, the internal wall of the acetabulum in Azendohsaurus is solid bone.[2]

The large sacral ribs articulate with the ilium so that it is held almost vertically, although their slight downward angle would have deflected the hip socket to face not only out away from the body but also down by about 10° to 25° from vertical. The femur is long and vaguely S-shaped, with a slightly expanded head that is not turned inwards, unlike those of dinosaurs, indicating it was not held upright. The femur is also twisted along its shaft so that the faces of the head and the knee are offset from each other by about ~75°. The tibia is roughly 75% the length of the femur, slightly bowed out, and is very robust compared those of other archosauromorphs except for the largest rhynchosaurs. The fibula by contrast is slender and more prominently twisted along its length.[2]

The extremities of Azendohsaurus are well represented in the fossils, including both a complete hand (manus) and foot (pes) each in articulation. All of the carpals and tarsal bones are well ossified and distinct, and the complicated tarsus is made up of nine bones. The metacarpals in the hand are notable as they diverge in a smooth arc, with the length of the digits almost symmetrical around the long third digit as well as relatively non-diverged first and fifth digits. This contrasts with the hands of other reptiles where first and fifth digits are spread out from each other and the fourth digit is the longest. The metatarsals and digits of the foot also diverge in a smooth arc, but unlike the hand they are not symmetrical, with a long fourth toe and a short, hooked fifth digit.[2]

All the digits of the hands and feet are unusually short for an archosauromorph, contrasting with the related Trilophosaurus. The claws (or unguals) are all very large, narrow and sharply recurved, and are significantly larger than the preceding finger bone they were attached to.[2] The digits and claws share features with those of dromaeosaurid and troodontid maniraptorans, as well as other reptiles such as the turtle Proganochelys. These shared traits are associated with well developed flexor tendons, and it is suggested to be an adaptation for withstanding forces involved in digging.[6]

History of Discovery

A. laaroussii

Early discoveries

The first fossils of Azendohsaurus laaroussii were discovered in a northern part the Timezgadiouine Formation in Morocco, which is found within the Argana Basin of the High Atlas. The fossil beds consist of sandstones and red clay mudstones, and were excavated by Jean-Michel Dutuit between 1962 and 1969. The fossils of A. laaroussii are known from only a single layer within the formation, in an outcrop numbered XVI by Dutuit at the base of the T5 (or Irohalene) member. The T5 member has traditionally been roughly dated to the early Late Triassic in age using vertebrate biostratigraphy based on the presence of the phytosaur "Paleorhinus" magnoculus, as part of the Carnian dated '"Palaeorhinus" biochron',[7] although this method of correlating and dating global Triassic sequences may be inaccurate and the date for the T5 member remains uncertain.[8][9]

The first fossils consisted of only a partial tooth-bearing dentary fragment and some associated teeth. This material was discovered by J. M. Dutuit in 1965 and described in 1972, who believed it to belong to a herbivorous ornithischian dinosaur, as well as one of the oldest dinosaurs yet discovered. He named the genus "Azendoh lizard", after the nearby Azendoh village located only 1.5 km to the west of where the fossils were discovered. The specific name, A. laaroussii, is in honour of Laaroussi, the name of a technician from the Moroccan geological mapping service who first discovered the site where Azendohsaurus was found.[4][10]

Dutuit's description of Azendohsaurus as an ornithischian was soon challenged by palaeontologist Richard Thulborn two years later in 1974, who was the first to suggest that Azendohsaurus was a "prosauropod" instead.[11] The same conclusion was made by José Boneparte after examining the material himself in 1976.[12] This re-identification was favoured by researchers in subsequent publications, and it was variously referred to the "prosauropod" families Anchisauridae[13][14] and Thecodontosauridae[15][16][17] without further explanation. Dutuit himself even agreed that Azendohsaurus was likely to be a "prosauropod" in 1983,[18] although not long before in 1981 he had briefly regarded it as a "pre-ornithischian".[4][19]

In 1985, palaeontologist Peter Galton suggested that Dutuit's original "Azandohsaurus [sic]" material included the jaw of a "prosauropod" and the tooth of a fabrosaurid ornithischian (a now defunct grouping of early ornithischians), based on the differences in the shape of the teeth.[20] This suggestion was refuted by François-Xavier Gauffre in 1993 when he re-described the material, as well describing additional jaw bones and teeth including two maxillae. He correctly concluded that the material belonged to a single taxon, but assigned the genus to "Prosauropoda" incertae sedis based again on the characteristics of the jaws and teeth. However, he could not determine its position within "Prosauropoda" due to the ambiguous distribution of these traits in early herbivorous dinosaurs, as well as a lack of any comparable Triassic reptiles, so he referred it to incertae sedis.[4] His assessment was accepted by many other researchers in the years following up until the description of the new material from the Madagascan species.[21][22][23][24][25][26]

Later finds to present

New material from the type locality of A. laaroussii, including parts of the post-cranial skeleton, was reported on in 2002 at the annual conference of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology by Nour-Eddine Jalil and Fabien Knoll. The additional material included presacral vertebrae, limb bones and limb girdles. The material was disarticulated, and was only attributable to A. laaroussii due to its association with recognised fragments of the skull and jaws. The post-cranial material was recognised as non-dinosaurian, but still believed to be an ornithodiran archosaur related to dinosaurs.[27] If correctly associated with the jaws and teeth, this indicated Azendohsaurus was not closely related to any herbivorous dinosaurs, despite their similarities.[28] Similarly, teeth from other purported Triassic ornithischians were later found to belong to previously unrecognised herbivorous reptiles, such as the pseudosuchian Revueltosaurus, highlighting the possibility for mistaken identities in other purported herbivorous Triassic dinosaurs, including Azendohsaurus.[29]

The new post cranial material from A. laaroussii was described as part of a Ph.D thesis by Khaldoune in 2014,[30] but as of 2019 this thesis has not yet been published and the material remains officially undescribed in published literature. However, it has now more confidently been referred to A. laaroussii after the description of the Madagascan material, and was found to share at least two diagnostic post cranial traits with the Madagascan species.[2][31] All the material from A. laaroussii, including the holotype and unpublished post crania, is housed at the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle in Paris, France .[31][32]

A. madagaskarensis

Initial discoveries

In 1997 through to 1999, fossils of a new archosauromorph were discovered by an international expedition in southwestern Madagascar and were recovered over the following decade. The fossils were found in a single bone bed, referred to as M-28, that was only tens of centimetres thick across a 100 metre stretch of outcrop exposed as an uplifted river terrace not far from the east bank of the Malio River, just outside of the Isalo National Park, north-west of the town of Ranohira and to the east of Sakahara. The locality was from the base of the Middle–Late Triassic Makay Formation, also referred to as Isalo II, a part of the Isalo "Group" in the Morondava Basin.[1][33][34]

Previously, the formation had been believed to be Early to Middle Jurassic in age, although the earlier discovery of the rhynchosaur Isalorhynchus had revised that estimate to the Middle Triassic. The tetrapod fossils recovered in the 1997–99 expedition confirmed the Isalo II was Triassic in age, but instead suggested a younger Carnian age. The age of the formation has also been correlated to the Santacruzodon Assemblage Zone (AZ) from the Santa Maria Formation in South America based on the shared genera of traversodontid cynodonts, with a similar late Ladinian or early Carnian age.[35] The Santacruzodon AZ has been more reliably dated through radioisotope U—Pb dating, suggesting a maximum depositional age of 237 ±1.5 million years in the early Carnian.[36]

The bone bed contained material from almost "a dozen" individuals of varying ages and size, all from a single species.[33] The material was very well preserved, generally preserving the three-dimensional shape of the bones with very little crushing or distortion in some of the specimens. Based on the state of preservation, some of the bones were believed to have been buried rapidly while others were exposed for longer on the surface, where they were weathered, cracked and possibly trampled on before burial.[2]

As with A. laaroussii, the teeth and jaws were the first material to be recovered and described from the bone bed. These were initially mistaken to belong two different species based on the difference in tooth shape in the upper and lower jaws, but one of them was recognised as closely resembling A. laaroussii, sharing a keel on the inside surface of the maxilla and expanded, leaf-shaped teeth, among other features. Like A. laaroussii, both of these supposed species were also misidentified as "prosauropods"; a species of Azendohsaurus or a related taxon and another, more typical "prosauropod".[34][37] Further discoveries of associated material clarified that all the jaw material and the rest of the skeletons were from a single, new species of Azendohsaurus.[1]

Reinterpretation

Even preliminary examination of the rest of the skull and skeleton from the Madagascan species confirmed that Azendohsaurus was not a dinosaur, and was instead an aberrant herbivorous archosauromorph that was only distantly related to dinosaurs, let alone sauropodomorphs.[33] A description of the cranial material was published first in May, 2010 by John J. Flynn and colleagues, who also officially named and diagnosed it as a new species of Azendohsaurus, Azendohsaurus madagaskarensis, named for its country of origin. This was also the first time Azendohsaurus was determined to be a non-dinosaur in the published literature.[1]

In December, 2015, the rest of the skeleton of A. madagaskarensis was formally described and published by Sterling J. Nesbitt and colleagues, providing the first detailed examination of the full anatomy of Azendohsaurus from the now almost completely known skeleton. In addition to comparing its anatomy, they were also able to analyse its evolutionary relationships to other Triassic reptiles in a phylogenetic context for the first time.[2]

The preservation of the material was described as "generally excellent" by Nesbitt and colleagues, and the amount of overlapping material made it easier to determine the original morphology from distorted and broken bones. Much of the material was found disarticulated and sometimes isolated, but a number of specific parts of the body were found articulated in life position, including sections of the neck, back, hands and feet. Most of the material was similarly sized, with a range of about 25% between the smallest and largest specimens, although the significance of this is not understood and it could be related to ontogeny, individual variation or sexual dimorphism.

The well preserved nature of much of the material also allowed for reinterpretations of parts of the skeleton of other archosauromorphs, such as the hand of Trilophosaurus. The hands of other archosauromorphs are often poorly known, and so their preservation in Azendohsaurus is considered important for understanding their evolution in early archosauromorphs. All the specimens of A. madagaskarensis are permanently housed in both the University of Antananarivo in Madagascar (including the holotype) and at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago , Illinois, including casts of some of the original specimens.[2]

Classification

Initial attempts

Azendohsaurus was first misidentified as an ornithischian dinosaur by Dutuit, based on shared characteristics of its teeth such as the leaf-like shape and the number of denticles.[10] It was later believed to be a sauropodomorph instead by other researchers, assigned to the defunct infraorder "Prosauropoda" (then believed to be a distinct monophyletic group related to sauropods, now known to be a paraphyletic grade) based on the morphology of its lower jaw, maxilla and teeth, such as the downward curving dentary and absence of a predentary bone, one of the characteristic traits of ornithischians.[11][14][26] These misidentifications were caused by the convergence in jaw and tooth shape between it and the herbivorous dinosaurs while its true phylogenetic relationships could not be realised due to the absence of other bones of the skull and skeleton.

The non-dinosaurian identity of Azendohsaurus was first hinted at after the discovery of additional skeletal material recovered from the type locality. This was based on the presence of traits such as a solid hip socket (acetabulum), and a proximal fourth trochanter on the femur that also lacked an inward-facing head, which are typical of dinosaur skeletons. While evidently not a dinosaur, it was tentatively interpreted as an ornithodiran archosaur, still closely related to dinosaurs.[27]

The discovery of more complete material from Madagascar prompted the first formal classification Azendohsaurus as non-dinosaurian by Flynn and colleagues in 2010 through a detailed description of its cranial anatomy and were able to clarify its relationships further. They instead recognised it to be a more basal archosauromorph, far removed dinosaurs and closely related to but outside of the clade of Archosauriformes. As well as the derived, sauropodomorph-like features, the skull also had numerous primitive traits for archosauromorphs, including an open-bottomed lower temporal fenestra, extensive palatal teeth, a pineal foramen and no external mandibular or antorbital fenestrae. However, its exact relationships still remained unknown beyond a position as an indeterminate non-archosauriform archosauromorph.[1][33]

Recognition of Allokotosauria

Azendohsaurus was included in a phylogenetic analysis of Triassic archosauromorphs for the first time in 2015 by Nesbitt and colleagues, utilising all of the new information from the skull and skeleton and a broad sample of various Triassic archosauromorph species, where it was recovered as closely related to other enigmatic herbivorous Triassic reptiles such as Trilophosaurus and Teraterpeton. This newly recognised grouping of archosauromorphs was named Allokotosauria, meaning "strange reptiles", for the unusual qualities of the reptiles that belonged to the group. Azendohsaurus was found to be the sister taxon of the family Trilophosauridae, and was recognised as the sole member of its own family, the Azendohsauridae, due its distinctiveness even amongst other allokotosaurs.[2] A similar result was recovered by another large analysis of archosauromorph phylogeny in 2016 by Martín D. Ezcurra, who found a monophyletic Allokotosauria containing Azendohsaurus and Trilophosaurus.[38]

Allokotosaurs are recognised as often having specialised jaws and teeth, as well as sharing a number of synapomorphies that include several reversals to more plesiomorphic (ancestral) traits of archosauromorphs, as well as at least two derived traits. The clade is considered to be well supported in these analyses. However, although closely related, the craniodental characteristics of allokotosaurs vary dramatically, and among them Azendohsaurus was characterised by having laterally compressed, serrated teeth present throughout the length of the jaws (unlike the 'beaked' jaws of trilophosaurids). Azendohsaurus broadly shares with other azendohsaurids features such as confluent nares, leaf-shaped teeth and a long neck, but Azendohsaurus itself is distinguished by the distinctive groove on the inside surface of the maxilla and tooth crowns that are expanded above the base.[3]

In 2017, another large allokotosaur was described from the Middle Triassic of India by Saradee Sengupta and colleagues, named Shringasaurus indicus. Shringasaurus was very similar to Azendohsaurus, and they were found to be closely related, supporting the existence of Azendohsauridae as a distinct family from the trilophosaurids. The same analysis also recovered Pamelaria, another long necked archosauromorph from India, as a basal azendohsaurid. Similarities between Pamelaria and Azendohsaurus had been noted by Nesbitt and colleagues in 2015, including confluent nares, serrated teeth and low cervical spines, but their analysis favoured a position in Allokotosauria basal to azendohsaurids.[2] The 2017 analysis also confirmed the close relationship between A. laaroussii and A. madagaskarensis within Azendohsauridae, strengthening their shared referral to the genus Azendohsaurus. A 2018 analysis of Triassic archosauromorphs failed to recover Allokotosauria, but still recovered both species of Azendohsaurus within a clade of azendohsaurids.[39] The cladogram below follows the results of Sengupta and colleagues in 2017:[3]

| Crocopoda |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A 2022 phylogenetic analysis supported a monophyletic Allokotosauria and confirmed that Azendohsaurus was a sister taxon of Shringasaurus, and that the clade consisting of the two genera was in turn most closely related to Malerisaurus and Pamelaria.[40]

| Allokotosauria |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Evolutionary significance

The number of convergent traits shared between Azendohsaurus and sauropodomorph dinosaurs is remarkably high, especially as all the shared features are interpreted as being homoplastic, meaning that they evolved completely independently of each other.[2] Some of the shared adaptations of the skeleton between Azendohsaurus and sauropodomorphs were previously considered to be unique to sauropodomorphs. However, the convergent evolution of these traits in Azendohsaurus as adaptations towards a herbivorous lifestyle show that they may be more broadly distributed amongst Triassic archosauromorphs, and do not necessarily indicate a close relationship to sauropodomorphs in fossil taxa.[33]

The pattern of convergences in Azendohsaurus is unusual, as they appear to have arisen in only the front half of the animal, while the sprawling back legs and short tail of Azendohsaurus are characteristically primitive of earlier archosauromorphs, very unlike the columnar hind limbs and long tail of sauropodomorphs.[1] This further highlights the non-uniform distribution and acquisition of typically sauropodomorph traits in other herbivorous archosauromorphs.[2]

The age of Azendohsaurus is also significant, as it was roughly coeval with the earliest known sauropodomorphs from Carnian South America, such as the lightweight, bipedal Saturnalia. However, Azendohsaurus resembles the later Norian sauropodomorphs more closely, both in general anatomy and its larger body size. This suggests that azendohsaurids had been the first reptiles to evolve as high browsing herbivores in Triassic ecosystems, prior to the evolution of the larger sauropodomorphs, which had previously been assumed to have been the first high browsing herbivores. It also indicates that the convergence between Azendohsaurus and sauropodomorphs did not occur under the same environmental circumstances, as Azendohsaurus was part of an initial wave of herbivory in archosauromorphs (along with rhynchosaurs, silesaurids and cynodonts) and large sauropodomorphs in a second wave (along with herbivorous pseudosuchians).[2]

Azendohsaurus also demonstrates that archosauromorphs were occupying roles as large herbivores in Triassic ecosystems earlier in their evolutionary history than had been assumed. These roles were previously thought to be dominated by large synapsids such as dicynodonts prior to the radiation of archosaurs in the Late Triassic, but Azendohsaurus suggests that earlier archosauromorphs were also capable of competing with synapsid herbivores.[3]

Palaeobiology

Feeding and diet

The leaf-shaped teeth of Azendohsaurus are clearly suited for a herbivorous lifestyle, and microwear—marks left on the tooth surface during feeding—on the teeth of A. madagaskarensis suggest they were used for browsing on vegetation that was not especially tough or woody, preferring softer (but firm) vegetation. The microwear patterns also show that it used a simple up-and-down motion of the jaw, and did not use complex jaw movement to chew its food like ornithischian dinosaurs or contemporary cynodonts.[41] This microwear has not yet been observed on the teeth of A. laaroussii, but it is unknown if this is a genuine feature relating to a difference in diet and feeding habits between the two species or if it is just a feature of preservation.[1]

The fully developed palatal teeth suggest that it was using them for feeding in a specialised manner. However, no functional studies have been performed on the palatal teeth so it is unknown exactly what they were used for, although their similar shape to the marginal teeth suggests they were used for processing similar food. A pterygoid from a younger individual of A. madagaskarensis has fewer rows of palatal teeth that are smaller in size than those of the larger, mature individuals, indicating that Azendohsaurus increased both the number and size of its palatal teeth as it grew into adulthood. Younger individuals also had fewer dentary teeth than adults, although the difference was much less extreme compared to the palatal teeth (16 compared to the 17 of mature specimens).[1][33]

Body posture

The body posture inferred for Azendohsaurus is a mixture of sprawled and semi-sprawled. The hind limbs have been interpreted as being completely sprawled outwards from the body, with its femur held straight out and the lower leg bent 90° beneath it at the knee, like a lizard. The forelimbs and shoulder girdle, however, suggest that the front of the body was held more upright than the hind quarters, with a partly downward directed shoulder socket and a humerus more suited for being held partially erect, and was similar in shape to those of sauropodomorphs. This unusual combination suggests that Azendohsaurus stood with its front end raised up off from the ground, which combined with its long, arched neck and small head, allowed it to browse relatively high off the ground, unlike contemporary low-browsing rhynchosaurs and cynodonts. Adapting to high-browsing could possibly explain the convergence between Azendohsaurus and sauropodomorphs, acquiring similar traits of the neck, forelimbs and spine to perform in similar niches. However, the more sprawling posture of Azendohsaurus probably inhibited high-browsing like that of the fully erect sauropodomorphs.[2]

Palaeopathology

Despite the multitude of specimens present in the bone bed that was examined, only a single pathology has been recorded in A. madagaskarensis. Specimen UA 7-16-99-620, one of the three preserved interclavicles, had been malformed so that the long posterior process had been sharply bent to the right, compared to the normal straight posterior processes of the other two interclavicles.[2]

Metabolism and growth

In 2019, thin slices were cut from the humerus, femur and tibia of specimens attributed to A. laaroussii for histological examination of the microscopic bone structure to try and determine the rate of growth in Azendohsaurus. The vascular density (the density of blood vessels in the bone tissue) in all three limb bones was found to be comparable to those of fast-growing birds and mammals, and the types of bone tissue identified—particularly energy-consuming fibrolamellar bone tissue—were interpreted as indicating a high resting metabolic rate that was in the range of living birds and mammals. It was inferred then that, like birds and mammals, Azendohsaurus would also likewise have been endothermic, or "warm-blooded". High resting metabolic rates similar to those of Azendohsaurus had been identified in other more derived archosauromorphs (such as Prolacerta), and analyses suggested that endothermy may then have been ancestrally present in archosauromorphs as far back as their common ancestor with allokotosaurs. This suggests that Azendohsaurus may then have been ancestrally endothermic.[31] By contrast, the related allokotosaur Trilophosaurus was previously found to not have any fibrolamellar bone tissue in its limb bones and so was inferred to have grown slowly.[42]

Palaeoecology

Although the two species of Azendohsaurus are known from disparate locations in North Africa and Madagascar, during the Middle to Late Triassic these regions were connected as part of the supercontinent Pangaea. Because of this, the two regions share broadly similar faunas, as well as sharing some with other regions of the globe at the time. For example, the cynodonts in Madagascar are similar to those also found in South America, and the Moroccan temnospondyls may be related to those found in eastern North America.[35][43] The climate was hot and dry at this time, but with evidence suggesting higher levels of rainfall during the Carnian, interrupting the increasing aridity trend and creating wetter environments around the globe.[44]

Timezgadiouine Formation, Morocco

Other reptiles from the base of the Irohalene (T5) member of the Timezgadiouine Formation contemporaneous with A. laaroussii include the phytosaur Arganarhinus,[45] the predatory rauisuchid Arganasuchus,[46] the herbivorous silesaurid Diodorus,[8] a paratypothoracisine aetosaur,[47][48] and procolophonid parareptiles,[4] as well as the stahleckeriid dicynodont Moghreberia, a synapsid.[21] Temnospondyl amphibians are represented by several genera of metoposauroids, including the metoposaurids Arganasaurus and Dutuitosaurus, and the latiscopid Almasaurus.[14] Fish are also known from the T5 member, including various ray-finned actinopterygians such as the locally endemic Dipteronotus gibbosus and Mauritanichthys, as well as other perleidiform and redfieldiiform fishes, alongside lobe-finned actinistians and lungfish such as Asiatoceratodus.[22][47][49][50][51]

The T5 member is composed of cyclical layers of bioturbated mudstone and sandstone deposited in a broad, semi-humid basin.[52] It has been interpreted as a system of brackish permanent lakes and sandbars, or alternatively sandy meandering rivers on a muddy floodplain. The fluvial or lacustrine sediments of the T5 member contrast with the playa sediments of the preceding T4 member, suggesting that it was deposited during an interval of increased rainfall.[53][54]

Numerous tracks and trackways from various animals are preserved, typically those of animals known from fossil remains such as phytosaurs, pseudosuchians, dinosauromorphs and basal archosauromorphs. The tracks also appear to indicate the presence of large to very-large dinosauromorphs or paracrocodylomorphs that are currently not yet known from skeletal remains. Additional traces mark the presence of burrowing invertebrates, bivalves, and clam shrimps.[55][56][57]

Makay Formation, Madagascar

In Madagascar, Azendohsaurus co-existed with the hyperodapedontine rhynchosaur Isalorhynchus,[58] the herbivorous traversodontid cynodonts Dadadon and Menadon, and the predatory chiniquodontid cynodont Chiniquodon kalanoro,[59] as well as an undescribed kannemeyeriiform dicynodont, a sphenodontian reptile,[33] a procolophonid parareptile,[58] the diminutive lagerpetid Kongonaphon,[60] various other undescribed dinosauromorphs, and an "enigmatic archosaur" of uncertain classification.[2] The faunal composition of the Isalo II is believed to represent a Middle Triassic Ladinian aged assemblage, existing prior to the appearance of dinosaurs and associated Late Triassic faunas, particularly aetosaurs and phytosaurs that are absent from the formation,[1] and also inferred from the dominance of traversodonts in the fauna.[59][61] However, this age assessment remains uncertain, and the formation is possibly from the younger early Late Triassic during the Carnian, as has been proposed for the T5 member of the Argana Formation.[2][34]

Fossils of A. madagaskarensis have been exclusively recovered from a deposit of fine grained red mudstone, while other fossil bearing localities in the formation consist of medium grained channel sands, possibly reflecting a habitat preference in the ecosystem distinct from other animals or unique behavioural trait. The absence of any other species in the bone bed may also support this. However, this speculation cannot be confirmed, and it could instead be attributed to preservation bias.[2]

Possible niche partitioning in diet, though, is supported by differences in the tooth microwear of A. madagaskarensis and the contemporary traversodont Dadadon. Dadadon was inferred to be capable of feeding on tough, hardy vegetation by using complex chewing, in contrast to the simpler dentition and processing of Azendohsaurus, which was better suited for eating leaves.[41] This may also be supported by its more elevated body posture and long neck.[2]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 Flynn, J.J.; Nesbitt, S.J.; Parrish, J.M.; Ranivoharimanana, L.; Wyss, A.R. (2010). "A new species of Azendohsaurus (Diapsida: Archosauromorpha) from the Triassic Isalo Group of southwestern Madagascar: cranium and mandible". Palaeontology 53 (3): 669–688. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2010.00954.x.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 2.25 2.26 Nesbitt, S.J.; Flynn, J.J.; Pritchard, A.C.; Parrish, M.J.; Ranivoharimanana, L.; Wyss, A.R. (2015). "Postcranial osteology of Azendohsaurus madagaskarensis (?Middle to Upper Triassic, Isalo Group, Madagascar) and its systematic position among stem archosaur reptiles.". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 398 (398): 1–126. doi:10.1206/amnb-899-00-1-126.1. ISSN 0003-0090. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286412354.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Sengupta, S.; Ezcurra, M.D.; Bandyopadhyay, S. (2017-08-21). "A new horned and long-necked herbivorous stem-archosaur from the Middle Triassic of India" (in En). Scientific Reports 7 (1): 8366. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-08658-8. ISSN 2045-2322. PMID 28827583. Bibcode: 2017NatSR...7.8366S.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Gauffre, F. X. (1993). "The prosauropod dinosaur Azendohsaurus laaroussii from the Upper Triassic of Morocco.". Palaeontology 36 (4): 897–908. https://www.palass.org/sites/default/files/media/publications/palaeontology/volume_36/vol36_part4_pp897-908.pdf.

- ↑ Sues, Hans-Dieter (2003). "An unusual new archosauromorph reptile from the Upper Triassic Wolfville Formation of Nova Scotia". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 40 (4): 635–649. doi:10.1139/e02-048. ISSN 0008-4077. Bibcode: 2003CaJES..40..635S.

- ↑ Headden, Jaime A. (December 11, 2015). "Azendohsaurus – Former Dinosaur – Recieves [sic] Makeover". The Bite Stuff. https://qilong.wordpress.com/2015/12/11/azendohsaurus-former-dinosaur-recieves-makeover/.

- ↑ Hunt, Adrian P.; Lucas, Spencer G. (1991). "The Paleorhinus biochron and the correlation of the non-marine Upper Triassic of Pangaea". Palaeontology 34 (2): 487–501. https://mail.palaeo-electronica.org/publications/palaeontology-journal/archive/34/2/article_pp487-501?view=abstract. Retrieved 2019-07-19.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Kammerer, Christian F.; Nesbitt, Sterling J.; Shubin, Neil H. (2012). "The First Silesaurid Dinosauriform from the Late Triassic of Morocco" (in en). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 57 (2): 277–284. doi:10.4202/app.2011.0015. ISSN 0567-7920. http://www.app.pan.pl/archive/published/app57/app20110015.pdf.

- ↑ Butler, Richard J. (2013). "'Francosuchus' trauthi is not Paleorhinus: implications for Late Triassic vertebrate biostratigraphy" (in en). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 33 (4): 858–864. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.740542. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Dutuit, J. M. (1972). "Decouverte d'un dinosaure ornithischien dans le Trias superieur de l'Atlas occidental marocain.". Comptes rendus de l'Académie des Sciences de Paris 275: 2841–2844.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Thulborn, Richard A. (1974). "A new heterodontosaurid dinosaur (Reptilia: Ornithischia) from the Upper Triassic Red Beds of Lesotho" (in en). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 55 (2): 151–175. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1974.tb01591.x. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ↑ Bonaparte, J. F. (1976). "Pisanosaurus mertii Casamiquela and the Origin of the Ornithischia". Journal of Paleontology 50 (5): 808–820.

- ↑ Carroll, Robert L. (1988). Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution. W. H. Freeman and Company. pp. 621. ISBN 0716718227. OCLC 922750908. https://archive.org/details/vertebratepaleon0000carr/page/621.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Shubin, Neil H.; Sues, Hans-Dieter (1991). "Biogeography of early Mesozoic continental tetrapods: patterns and implications" (in en). Paleobiology 17 (3): 214–230. doi:10.1017/S0094837300010575. ISSN 0094-8373.

- ↑ Galton, P. M. (1990). "Basal Sauropodomorpha—Prosauropoda". in Weishampel, D. B.. The Dinosauria. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 335, 338. ISBN 9780520067264. OCLC 154697781.

- ↑ In the shadow of the dinosaurs: early Mesozoic tetrapods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1994. ISBN 0521452422. OCLC 28293773.

- ↑ Galton, Peter M.; Heerden, Jacques (1998). "Anatomy of the prosauropod dinosaur Blikanasaurus cromptoni (Upper Triassic, South Africa), with notes on the other tetrapods from the lower Elliot Formation" (in en). Paläontologische Zeitschrift 72 (1–2): 163–177. doi:10.1007/bf02987824. ISSN 0031-0220. https://www.academia.edu/21926394.

- ↑ Dutuit, J. M.; Heyler, Daniel (1983). "Taphonomie des gisements de Vertebres triasiques marocains (couloir d'Argana) et paleogeographie" (in en). Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France S7-XXV (4): 629. doi:10.2113/gssgfbull.s7-xxv.4.623. ISSN 0037-9409.

- ↑ Biron, P. E.; Dutuit, J. M. (1981). "Figurations sédimentaires et traces d'activité au sol dans le Trias de la formation d'Argana et de l'Ourika (Maroc).". Bulletin du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Section C 3 (4): 399–427. ISSN 0181-0642.

- ↑ GALTON, PETER M. (1985). "Diet of prosauropod dinosaurs from the late Triassic and early Jurassic" (in en). Lethaia 18 (2): 105–123. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1985.tb00690.x. ISSN 0024-1164. https://www.academia.edu/21926391.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Lucas, Spencer G. (1998). "Global Triassic tetrapod biostratigraphy and biochronology". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 143 (4): 347–384. doi:10.1016/s0031-0182(98)00117-5. ISSN 0031-0182. Bibcode: 1998PPP...143..347L. http://doc.rero.ch/record/16228/files/PAL_E3457.pdf.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Jalil, N.-E. (1999). "Continental Permian and Triassic vertebrate localities from Algeria and Morocco and their stratigraphical correlations". Journal of African Earth Sciences 29 (1): 219–226. doi:10.1016/s0899-5362(99)00091-3. ISSN 1464-343X. Bibcode: 1999JAfES..29..219J.

- ↑ Langer, Max C.; Abdala, Fernando; Richter, Martha; Benton, Michael J. (1999). "A sauropodomorph dinosaur from the Upper Triassic (Carnian) of southern Brazil". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences, Série IIA 329 (7): 511–517. doi:10.1016/s1251-8050(00)80025-7. ISSN 1251-8050. Bibcode: 1999CRASE.329..511L. http://palaeo.gly.bris.ac.uk/Benton/reprints/1999Saturnalia.pdf. Retrieved 2019-07-19.

- ↑ Yates, Adam M.; Kitching, James W. (2003-08-22). "The earliest known sauropod dinosaur and the first steps towards sauropod locomotion" (in en). Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 270 (1525): 1753–1758. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2417. ISSN 0962-8452. PMID 12965005. PMC 1691423. http://europepmc.org/backend/ptpmcrender.fcgi?accid=PMC1691423&blobtype=pdf.

- ↑ Durand, J.F. (2005). "Major African contributions to Palaeozoic and Mesozoic vertebrate palaeontology". Journal of African Earth Sciences 43 (1–3): 53–82. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2005.07.014. ISSN 1464-343X. Bibcode: 2005JAfES..43...53D.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Irmis, R.B.; Parker, W.G.; Nesbitt, S.J.; Liu, J. (2007). "Early ornithischian dinosaurs: the Triassic record". Historical Biology 19 (1): 3–22. doi:10.1080/08912960600719988. http://socrates.berkeley.edu/~irmisr/trornith.pdf.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Jalil, Nour-Eddine; Knoll, Fabien (2002). "Is Azendohsaurus laaroussii (Carnian, Morocco) a dinosaur?". Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 62nd Annual Meeting. 62. Norman, Oklahoma. p. 70A. http://www.miketaylor.org.uk/tmp/svp-abstracts/SVP%202002%20abstracts.pdf.

- ↑ Galton, P. M.; Upchurch, P. (2004). "Prosauropoda". in Weishampel, D. B.. The Dinosauria, second edition. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 232–258. ISBN 9780520254084. OCLC 154697781. https://archive.org/details/dinosauriandedit00weis.

- ↑ Parker, William G.; Irmis, Randall B.; Nesbitt, Sterling J.; Martz, Jeffrey W.; Browne, Lori S. (2005-05-07). "The Late Triassic pseudosuchian Revueltosaurus callenderi and its implications for the diversity of early ornithischian dinosaurs" (in en). Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences 272 (1566): 963–969. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.3047. ISSN 0962-8452. PMID 16024353. PMC 1564089. http://europepmc.org/backend/ptpmcrender.fcgi?accid=PMC1564089&blobtype=pdf.

- ↑ Khaldoune, F. (2014). Les vertébrés du Permien et du Trias du Maroc (Bassin d'Argana, Haut Atlas Occidental) avec la réévaluation d'Azendohsaurus laaroussii (Reptilia, Archosauromorpha) et la description de Reptilia Moradisaurinae et Rhynchosauria nouveaux: anatomie, relations phylogénétiques et implications biostratigraphiques (Unpublished Ph.D thesis) (in français). University Cadi Ayyad, Marrakesh, Morocco.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Cubo, J.; Jalil, N.-E. (2019). "Bone histology of Azendohsaurus laaroussii: Implications for the evolution of thermometabolism in Archosauromorpha". Paleobiology 45 (2): 317–330. doi:10.1017/pab.2019.13. https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-02969492/file/Cubo%20et%20Jalil%20-%202019%20-%20Bone%20histology%20of%20Azendohsaurus%20laaroussii%20Implic.pdf.

- ↑ Pritchard, Adam C.; Nesbitt, Sterling J. (2017). "A bird-like skull in a Triassic diapsid reptile increases heterogeneity of the morphological and phylogenetic radiation of Diapsida" (in en). Royal Society Open Science 4 (10): 170499. doi:10.1098/rsos.170499. ISSN 2054-5703. PMID 29134065. Bibcode: 2017RSOS....470499P.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 33.5 33.6 Flynn, J.; Nesbitt, S.; Parrish, M.; Ranivoharimanana, L.; Wyss, A. (2008). "A new species of basal archosauromorph from the Late Triassic of Madagascar". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 28 (Suppl. 3): 78A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2008.10010459.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Flynn, John J.; Parrish, J. Michael; Rakotosamimanana, Berthe; Simpson, William F.; Whatley, Robin L.; Wyss, André R. (1999-10-22). "A Triassic Fauna from Madagascar, Including Early Dinosaurs" (in en). Science 286 (5440): 763–765. doi:10.1126/science.286.5440.763. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 10531059.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Melo, T.P.; Abdala, F.; Soares, M.B. (2015). "The Malagasy cynodont Menadon besairiei (Cynodontia; Traversodontidae) in the Middle-Upper Triassic of Brazil". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 5 (6): e1002562. doi:10.1080/02724634.2014.1002562. ISSN 1937-2809. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282351998.

- ↑ Schmitt, M.R.; Martinelli, A.G.; Melo, T.P.; Soares, M.B. (2019). "On the occurrence of the traversodontid Massetognathus ochagaviae (Synapsida, Cynodontia) in the early late Triassic Santacruzodon Assemblage Zone (Santa Maria Supersequence, southern Brazil): Taxonomic and biostratigraphic implications". Journal of South American Earth Sciences 93: 36–50. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2019.04.011. Bibcode: 2019JSAES..93...36S.

- ↑ Flynn, John J.; Parrish, J. Michael; Rakotosamimanana, Berthe; Ranivoharimanana, Lovasoa; Simpson, William F.; Wyss, André R. (2000-09-25). "New Traversodontids (Synapsida: Eucynodontia) from the Triassic of Madagascar" (in en). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 20 (3): 422–427. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2000)020[0422:ntseft2.0.co;2]. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ↑ Ezcurra, M.D. (2016). "The phylogenetic relationships of basal archosauromorphs, with an emphasis on the systematics of proterosuchian archosauriforms" (in en). PeerJ 4: e1778. doi:10.7717/peerj.1778. ISSN 2167-8359. PMID 27162705.

- ↑ Pritchard, Adam C.; Gauthier, Jacques A.; Hanson, Michael; Bever, Gabriel S.; Bhullar, Bhart-Anjan S. (2018-03-23). "A tiny Triassic saurian from Connecticut and the early evolution of the diapsid feeding apparatus" (in En). Nature Communications 9 (1): 1213. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-03508-1. ISSN 2041-1723. PMID 29572441. Bibcode: 2018NatCo...9.1213P.

- ↑ Sengupta, Saradee; Bandyopadhyay, Saswati (21 February 2022). "The osteology of Shringasaurus indicus, an archosauromorph from the Middle Triassic Denwa Formation, Satpura Gondwana Basin, Central India". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 41 (5). doi:10.1080/02724634.2021.2010740. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02724634.2021.2010740. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Goswami, A.; Flynn, J.J.; Ranivoharimanana, L.; Wyss, A.R. (2005). "Dental microwear in Triassic amniotes: implications for paleoecology and masticatory mechanics.". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 25 (2): 320–329. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0320:DMITAI2.0.CO;2]. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228659761.

- ↑ Werning, S.; Irmis, R. (2010). "Reconstructing the ontogeny of the Triassic basal archosauromorph Trilophosaurus using bone histology and limb bone morphometrics". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30 (Supp. 2: 70th Anniversary Meeting Society Of Vertebrate Paleontology): 185A–186A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.10411819. http://vertpaleo.org/Annual-Meeting/Future-Past-Meetings/MeetingPdfs/2010AnnualMeetingAbstracts.aspx. Retrieved 2019-07-19.

- ↑ Gee, B.M.; Paerker, W.G.; Marsh, A.D. (2020). "Redescription of Anaschisma (Temnospondyli: Metoposauridae) from the Late Triassic of Wyoming and the phylogeny of the Metoposauridae". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 18 (3): 233–258. doi:10.1080/14772019.2019.1602855. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/natlpark/197.

- ↑ Ruffell, A.; Simms, M.J.; Wignell, P.B. (2016). "The Carnian Humid Episode of the late Triassic: a review". Geological Magazine 153 (Special Issue 2): 271–284. doi:10.1017/S0016756815000424. Bibcode: 2016GeoM..153..271R. http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/90239/1/Carnian%20humidity%20final%20version.pdf.

- ↑ Dutuit, Jean-Michel (1977). "Paleorhinus magnoculus, Phytosaure du Trias supérieur de l'Atlas marocain" (in fr-FR). Géologie Méditerranéenne 4 (3): 255–267. doi:10.3406/geolm.1977.1007. ISSN 0397-2844. https://www.persee.fr/docAsPDF/geolm_0397-2844_1977_num_4_3_1007.pdf.

- ↑ Jalil, Nour-Eddine; Peyer, Karin (2007). "A new Rauisuchian (Archsauria, Suchia) from the Upper Triassic of the Argana Basin, Morocco" (in en). Palaeontology 50 (2): 417–430. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00640.x. ISSN 0031-0239.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Lucas, Spencer G. (1998). "The aetosaur Longosuchus from the Triassic of Morocco and its biochronological significance". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences, Série IIA 326 (8): 589–594. doi:10.1016/s1251-8050(98)80211-5. ISSN 1251-8050. Bibcode: 1998CRASE.326..589L.

- ↑ Parker, William G.; Martz, Jeffrey W. (2010-07-14). "Using positional homology in aetosaur (Archosauria: Pseudosuchia) osteoderms to evaluate the taxonomic status of Lucasuchus hunti" (in en). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30 (4): 1100–1108. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.483536. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ↑ Martin, M. (1980). "Mauritanichthys rugosus n. gen. et n. sp., Redfieldiidae (Actinopterygi, Chondrostei) du Trias Superieur continental marocain [Mauritanichthys rugosus n. gen. et n. sp., Redfieldiidae (Actinopterygi, Chondrostei) from the continental Moroccan Upper Triassic]". Géobios 13 (3): 437–441. doi:10.1016/S0016-6995(80)80078-7.

- ↑ Martin, M. (1980). "Dipteronotus gibbosus (Actinopterygi, Chondrostei), nouveau Colobodontidae du Trias Superieur continental marocain [Dipteronotus gibbosus (Actinopterygi, Chondrostei), new Colobodontidae from the continental Moroccan Upper Triassic]". Géobios 13 (3): 445–449. doi:10.1016/S0016-6995(80)80080-5.

- ↑ Martin, M. (1982). "Les Actinoptérygiens (Perleidifomes et Redfieldiiformes) du Trias supérieur continental du couloir d'Argana (Atlas occidental, Maroc) [The actinopterygians (Perleidiformes and Redfieldiiformes) from the continental Upper Triassic of the Argana valley (western Atlas, Morocco)]". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 162 (3): 352–372.

- ↑ Baudon, Catherine; Redfern, Jonathan; Van Den Driessche, Jean (2012-04-09). "Permo-Triassic structural evolution of the Argana Valley, impact of the Atlantic rifting in the High Atlas, Morocco" (in en). Journal of African Earth Sciences 65: 91–104. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2012.02.002. ISSN 1464-343X. https://www.academia.edu/11210616.

- ↑ Brown, Roy H. (1980-07-01). "Triassic Rocks of Argana Valley, Southern Morocco, and Their Regional Structural Implications". AAPG Bulletin 64 (7): 988–1003. doi:10.1306/2F919418-16CE-11D7-8645000102C1865D. ISSN 0149-1423. https://doi.org/10.1306/2F919418-16CE-11D7-8645000102C1865D.

- ↑ Hofmann, Axel; Tourani, Abdelilah; Gaupp, Reinhard (2000). "Cyclicity of Triassic to Lower Jurassic continental red beds of the Argana Valley, Morocco: implications for palaeoclimate and basin evolution". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 161 (1–2): 229–266. doi:10.1016/s0031-0182(00)00125-5. ISSN 0031-0182. Bibcode: 2000PPP...161..229H. https://www.academia.edu/7569221.

- ↑ Lagnaoui, A.; Klein, H.; Voigt, S.; Hminna, A.; Saber, H.; Schneider, J.W.; Werneburg, R. (2012). "Late Triassic Tetrapod-Dominated Ichnoassemblages from the Argana Basin (Western High Atlas, Morocco)" (in en). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 19 (4): 238–253. doi:10.1080/10420940.2012.718014. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234033566.

- ↑ Lagnaoui, A.; Klein, H.; Saber, H.; Fekkak, A.; Belahmira, A.; Schneider, J.W. (2016). "New discoveries of archosaur and other tetrapod footprints from the Timezgadiouine Formation (Irohalene Member, Upper Triassic) of the Argana Basin, western High Atlas, Morocco – Ichnotaxonomic implications" (in en). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 453: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.03.022. Bibcode: 2016PPP...453....1L. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301550793.

- ↑ Zouheir, Tariq; Hminna, Abdelkbir; Klein, Hendrik; Lagnaoui, Abdelouahed; Saber, Hafid; Schneider, Joerg W. (2018). "Unusual archosaur trackway and associated tetrapod ichnofauna from Irohalene member (Timezgadiouine formation, late Triassic, Carnian) of the Argana Basin, Western High Atlas, Morocco" (in en). Historical Biology 32 (5): 589–601. doi:10.1080/08912963.2018.1513506. ISSN 0891-2963. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327298375.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Langer, Max; Boniface, Michael; Cuny, Gilles; Barbieri, Laurent (2000). "The phylogenetic position of Isalorhynchus genovefae, a Late Triassic rhynchosaur from Madagascar". Annales de Paléontologie 86 (2): 101–127. doi:10.1016/s0753-3969(00)80002-6. ISSN 0753-3969. http://www.paleolab.com.br/assets/uploads/files/pdf/Langer_et_al_2000a.pdf.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Kammerer, C.F.; Flynn, J.J.; Ranivoharimanana, L.; Wyss, A.R. (2010). "The First Record of a Probainognathian (Cynodontia: Chiniquodontidae) from the Triassic of Madagascar". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30 (6): 1889–1894. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.520784.

- ↑ Kammerer, Christian F.; Nesbitt, Sterling J.; Flynn, John J.; Ranivoharimanana, Lovasoa; Wyss, André R. (2020-07-02). "A tiny ornithodiran archosaur from the Triassic of Madagascar and the role of miniaturization in dinosaur and pterosaur ancestry" (in en). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117 (30): 17932–17936. doi:10.1073/pnas.1916631117. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 32631980.

- ↑ Langer, Max Cardoso (2005). "Studies on continental Late Triassic tetrapod biochronology. II. The Ischigualastian and a Carnian global correlation". Journal of South American Earth Sciences 19 (2): 219–239. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2005.04.002. ISSN 0895-9811. Bibcode: 2005JSAES..19..219L. http://doc.rero.ch/record/232971/files/PAL_E4557.pdf.

Wikidata ☰ Q2294166 entry

|