Biology:Josephoartigasia monesi

| Josephoartigasia monesi | |

|---|---|

| |

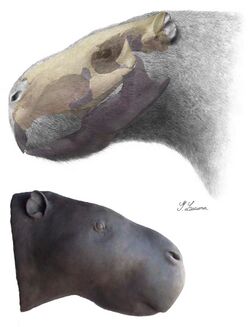

| Life restoration of J. monesi | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Dinomyidae |

| Genus: | †Josephoartigasia |

| Species: | †J. monesi

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Josephoartigasia monesi | |

Josephoartigasia monesi, an extinct species of South American caviomorph rodent, is the largest rodent known, and lived from about 4 to 2 million years ago during the Pliocene to early Pleistocene.[1][notes 1] The species is one of two in the genus Josephoartigasia, the other being J. magna.[1] J. monesi is sometimes called the giant pacarana, after its closest living relative, the pacarana (Dinomys branickii).[1] Josephoartigasia is estimated to have weighed about 500 kg (1,102 lb), making it about the size of a horse (Equus ferus caballus).[2]

Description

The skull of the holotype is 53 cm (21 in) long, and the remaining incisor is more than 30 cm (12 in) in length. The total estimated body length is 2.6 m (9 ft), with a height of 1.5 m (5 ft). Josephoartigasia had a relatively long snout compared to other caviomorph rodents, which has been suggested to be related to its large size, strong bite, and tusk-like incisors.[3][2][4]

Body mass

Josephoartigasia monesi is the largest known species of rodent to have ever existed, much larger than even other large, extinct caviomorph species such as Phoberomys insolita and Phoberomys pattersoni. Josephoartigasia monesi is only known from a single skull, which has made reconstructing the size of this extinct rodent difficult. Originally, J. monesi was estimated to have been 1,211 kg (2,670 lb), with estimated body sizes ranging between 468 and 2,586 kg (1,032 and 5,701 lb), comparable in size to large ruminant mammals like cattle (Bos taurus) at 770 kg (1,700 lb) or plains bison (Bison bison) at 900 kg (2,000 lb).[1] Millien (2008) considered these mass estimates to be too high due to statistical errors in the estimation, and produced a more conservative estimate of 350 to 1,534 kg (772 to 3,382 lb), with a median of 900 kg (2,000 lb).[3] Nevertheless, some of the original describers of J. monesi disagreed with the conclusions of Millien (2008).[5] Some other specialists on South American mammals expressed skepticism about the high mass estimates for Josephoartigasia.[6] Engelman (2022) revisited the body mass of J. monesi and other large caviomorphs like Phoberomys, and produced estimates of 483 to 576 kg (1,065 to 1,270 lb) with a maximum confidence interval 224 to 1,350 kg (494 to 2,976 lb) of using multiple methods, including skull length and occipital condyle width.[2] Notably, Engelman (2022) was unable to replicate the high estimates of previous studies even when incorporating assumptions that inflated body mass values.[2]

Discovery and etymology

Josephoartigasia monesi is known from an almost complete skull, which was recovered from the San José Formation on the coast of Río de la Plata in Uruguay.[1] Discovered in 1987, but not scientifically described until 2008, the specimen is preserved in Uruguay's National Museum of Natural History.[7] Josephoartigasia monesi was named after Uruguay national hero José Gervasio Artigas and the paleontologist Álvaro Mones, for his study on the rodent in 1966.[1]

Paleobiology

The rodent's fearsome front teeth and large size may have been used to fight over females for breeding rights and may also have helped defend against predators, including sparassodonts, saber-toothed cats and terror birds.[8]

The rodent may have lived in an estuarine environment or a delta system with forest communities,[1] and may have eaten soft vegetation.[9] It has been stated that J. monesi probably fed on aquatic plants and fruits, because its molars are small and not good for grass or other abrasive vegetation. Larger mammals also have the advantage of access to low-quality food resources, such as wood, that smaller species are unable to digest.[8]

Finite element analysis was used to estimate the maximum bite force of J. monesi.[10] This study concluded that the bite of J. monesi possibly generated up to 4165 N of force, three times as powerful as predicted for modern day tigers.[11] The study also speculated that J. monesi behaved similarly to elephants, utilizing its incisors like tusks for digging or defense.[10]

Notes

- ↑ According to Rinderknecht & Blanco 2008, recent studies indicate that some strata of the San José Formation, in which the specimen was found, are Pleistocene, instead of Pliocene as was previously assumed. In any case, they do give a date range of 4–2 Mya.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Rinderknecht, Andrés; Blanco, R. Ernesto (January 2008). "The largest fossil rodent". Proceedings of the Royal Society B 275 (1637): 923–8. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1645. PMID 18198140.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Engelman, Russell K. (June 2022). "Resizing the largest known extinct rodents (Caviomorpha: Dinomyidae, Neoepiblemidae) using occipital condyle width". Royal Society Open Science 9 (6): 220370. doi:10.1098/rsos.220370.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Millien, Virginie (May 2008). "The largest among the smallest: the body mass of the giant rodent Josephoartigasia monesi". Proceedings of the Royal Society B 275 (1646): 1953–5; discussion 1957–8. doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.0087. PMID 18495621.

- "Biggest rodent 'shrinks in size'". BBC News. 20 May 2008. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/7408743.stm.

- ↑ Blanco, R. Ernesto; Rinderknecht, Andrés; Lecuona, Gustavo (April 2012). "The bite force of the largest fossil rodent (Hystricognathi, Caviomorpha, Dinomyidae): Largest rodent bite force". Lethaia 45 (2): 157–163. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.2011.00265.x.

- ↑ Blanco, R. Ernesto (7 September 2008). "The uncertainties of the largest fossil rodent". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 275 (1646): 1957–1958. doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.0551.

- ↑ Croft, Darin A. (22 November 2019). "R.O.U.S. for Real" (in en). https://raftingmonkey.com/2019/11/22/r-o-u-s-for-real/.

- ↑ Satter, Raphael G. (2008-01-16). "Fossil remains of 2,000-pound rodent found". NBC News. http://www.nbcnews.com/id/22684589.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Owen, James (16 January 2008). "Bull-Size Rodent Discovered -- Biggest Yet". National Geographic News. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2008/01/080116-giant-rodent.html.

- ↑ Brahic, Catherine (2008-01-16). "One-tonne rodent discovered in South America". New Scientist. https://www.newscientist.com/channel/life/dn13188-onetonne-rodent-discovered-in-south-america.html.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Cox, Philip G.; Rinderknecht, Andrés; Blanco, R. Ernesto (2015). "Predicting bite force and cranial biomechanics in the largest fossil rodent using finite element analysis". Journal of Anatomy 226 (3): 215–23. doi:10.1111/joa.12282. PMID 25652795.

- ↑ Perkins, Sid (2015). "Ratzilla: Ancient giant rodent chomped like a crocodile". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aaa7792.

Wikidata ☰ Q133298 entry