Astronomy:6dF Galaxy Survey

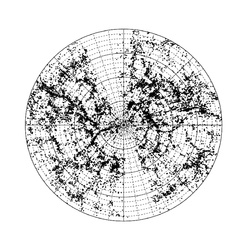

6dF view with -10 - 0 degree (DEC), 360 degree (RA) and 0 - 200 Mpc radius. Each black dot represents a galaxy. | |

| Survey type | Redshift survey |

|---|---|

The 6dF Galaxy Survey (Six-degree Field Galaxy Survey), 6dF or 6dFGS is a redshift survey conducted by the Anglo-Australian Observatory (AAO) with the 1.2m UK Schmidt Telescope between 2001 and 2009. The data from this survey were made public on 31 March, 2009.[1] The survey has mapped the nearby universe over nearly half the sky. Its 136,304 spectra have yielded 110,256 new extragalactic redshifts and a new catalog of 125,071 galaxies. For a subsample of 6dF a peculiar velocity survey is measuring mass distribution and bulk motions of the local Universe. As of July 2009, it is the third largest redshift survey next to the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) and the 2dF Galaxy Redshift Survey (2dFGRS).

Description

The 6dF survey covers 17,000 deg2 of the southern sky which is approximately ten times the area of the 2dFGRS[2] and more than twice the spectroscopic areal coverage of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey.[3] All redshifts and spectra are available through the 6dFGS Online Database, hosted at the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh. An online 6dFGS atlas is available through the University of Cape Town.

The survey was carried out with the 1.2 meter UK Schmidt Telescope at Siding Spring Observatory in New South Wales, Australia with the 6dF instrument permitting the observation of a field of 6 degrees per pointing. The instrument possesses a multi-object fiber spectrograph with 150 optical fibers per field plate.

One feature of the 6dF Galaxy Survey compared to earlier redshift and peculiar velocity surveys is its near-infrared source selection. The main target catalogs are selected from the Two Micron All Sky Survey.[4] There are several advantages of choosing galaxies in these bands.

- The near-infrared spectral energy distributions of galaxies are dominated by the light of their oldest stellar populations, and hence, the bulk of their stellar mass. Traditionally, surveys have selected target galaxies in the optical where galaxies dominated by younger, bluer stars.

- The effects of dust extinction are smaller at longer wavelengths. For the target galaxies, this means that the total near-infrared luminosity is not dependent on galaxy orientation and so provides a reliable measure of galaxy mass. Furthermore, this means the 6dF can map the local Universe nearer to the plane of the Milky Way than would otherwise be possible through optical selection.

Baryon Acoustic Oscillation detection

The 6dF survey is one of the few surveys which are big enough to allow a baryon acoustic oscillation (BAO) signal to be detected. The low redshift of 6dF made it possible to derive the Hubble constant H0 with an uncertainty competitive with the distance ladder technique. The result is reported in Beutler et al. (2011)[5] and is given by H0 = 67 ± 3.2 km/s/Mpc.

The peculiar velocity survey

The redshift of a galaxy includes the recessional velocity cause by the expansion of the Universe (see Hubble's law) and the peculiar velocity of the galaxy itself. Therefore, a redshift survey alone does not provide an accurate three-dimensional distribution for the galaxies. However, by measuring both components separately, it is possible to obtain a survey of the (peculiar) velocities of the galaxies. In the 6dF survey distance estimators are based on the Fundamental plane of early-type galaxies.[6] This requires measurements of the galaxies' internal velocity dispersions which is much more difficult than the determination of the redshift. This restricts the number of galaxies usable for the peculiar velocity survey to about 10% of the overall 6dF galaxies. Finally the peculiar velocities can be measured as the discrepancy between the redshift and the estimated distance.

References

External links

|