Astronomy:Argo Navis

Argo Navis (the Ship Argo), or simply Argo, is one of Ptolemy's 48 constellations, now a grouping of three IAU constellations. It is formerly a single large constellation in the southern sky. The genitive is "Argus Navis", abbreviated "Arg". Flamsteed and other early modern astronomers called it Navis (the Ship), genitive "Navis", abbreviated "Nav".

The constellation proved to be of unwieldy size, as it was 28% larger than the next largest constellation and had more than 160 easily visible stars. The 1755 catalogue of Nicolas Louis de Lacaille divided it into the three modern constellations that occupy much of the same area: Carina (the keel), Puppis (the poop deck or stern), and Vela (the sails).

Argo derived from the ship Argo in Greek mythology, sailed by Jason and the Argonauts to Colchis in search of the Golden Fleece.[1] Some stars of Puppis and Vela can be seen from Mediterranean latitudes in winter and spring, the ship appearing to skim along the "river of the Milky Way."[2] The precession of the equinoxes has caused the position of the stars from Earth's viewpoint to shift southward. Though most of the constellation was visible in Classical times, the constellation is now not easily visible from most of the northern hemisphere.[3] All the stars of Argo Navis are easily visible from the tropics southward and pass near zenith from southern temperate latitudes. The brightest of these is Canopus (α Carinae), the second-brightest night-time star, now assigned to Carina.

History

Development of the Greek constellation

Argo Navis is known from Greek texts, which derived it from Egypt around 1000 BC.[4] Plutarch attributed it to the Egyptian "Boat of Osiris."[4] Some academics theorized a Sumerian origin related to the Epic of Gilgamesh, a hypothesis rejected for lack of evidence that Mesopotamian cultures considered these stars, or any portion of them, to form a boat.[4]

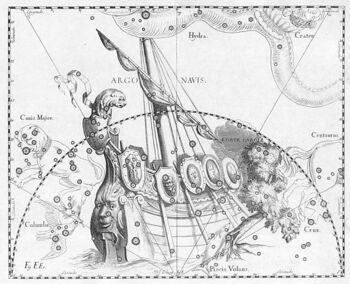

Over time, Argo became identified exclusively with ancient Greek myth of Jason and the Argonauts. In Ptolemy's Almagest, Argo Navis occupies the portion of the Milky Way between Canis Major and Centaurus, with stars marking such details as the "little shield", the "steering-oar", the "mast-holder", and the "stern-ornament",[5] which continued to be reflected in cartographic representations in celestial atlases into the nineteenth century (see below). The ship appeared to rotate about the pole sternwards, so nautically in reverse. Aratus, the Greek poet / historian living in the third century BCE, noted this backward progression writing, "Argo by the Great Dog's [Canis Major's] tail is drawn; for hers is not a usual course, but backward turned she comes ...".[6]

The constituent modern constellations

In modern times, Argo Navis was considered unwieldy due to its enormous size (28% larger than Hydra, the largest modern constellation).[1] In his 1763 star catalogue, Nicolas Louis de Lacaille explained that there were more than a hundred and sixty stars clearly visible to the naked eye in Navis, and so he used the set of lowercase and uppercase Latin letters three times on portions of the constellation referred to as "Argûs in carina" (Carina, the keel), "Argûs in puppi" (Puppis, the poop deck or stern), and "Argûs in velis" (Vela, the sails).[7] Lacaille replaced Bayer's designations with new ones that followed stellar magnitudes more closely, but used only a single Greek-letter sequence and described the constellation for those stars as "Argûs". Similarly, faint unlettered stars were listed only as in "Argûs".[8]

The final breakup and abolition of Argo Navis was proposed by Sir John Herschel in 1841 and again in 1844.[9] Despite this, the constellation remained in use in parallel with its constituent parts into the 20th century. In 1922, along with the other constellations, it received a three-letter abbreviation: Arg.[10] The breakup and relegation to a former constellation occurred in 1930 when the IAU defined the 88 modern constellations, formally instituting Carina, Puppis, and Vela, and declaring Argo obsolete.[11] Lacaille's designations were kept in the offspring, so Carina has α, β, and ε; Vela has γ and δ; Puppis has ζ; and so on.[12]: 82 As a result of this breakup, Argo Navis is the only one of Ptolemy's 48 constellations that is no longer officially recognized as a single constellation.[13]

In addition, the constellation Pyxis (the mariner's compass) occupies an area near what in antiquity was considered part of Argo's mast. Some recent authors state that the compass was part of the ship,[14][15] but magnetic compasses were unknown in ancient Greek times.[1] Lacaille considered it a separate constellation representing a modern scientific instrument (like Microscopium and Telescopium), that he created for maps of the stars of the southern hemisphere. Pyxis was listed among his 14 new constellations.[lower-alpha 1][8][12]: 262 In 1844, John Herschel suggested formalizing the mast as a new constellation, Malus, to replace Lacaille's Pyxis, but the idea did not catch on.[1] Similarly, an effort by Edmond Halley to detach the "cloud of mist" at the prow of Argo Navis to form a new constellation named Robur Carolinum (Charles' Oak) in honor of King Charles II, his patron, was unsuccessful.[16]

Representations in other cultures

In Vedic period astronomy, which drew its zodiac signs and many constellations from the period of the Indo-Greek Kingdom, Indian observers saw the asterism as a boat.[17]

The Māori had several names for the constellation, including Te Waka-o-Tamarereti (the canoe of Tamarereti),[18] Te Kohi-a-Autahi (an expression meaning "cold of autumn settling down on land and water"),[19] and Te Kohi.[20]

See also

Footnotes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Ridpath, Ian. "Argo Navis". http://www.ianridpath.com/startales/argo.html.

- ↑ Massey, Gerald. Ancient Egypt – Light Of The World, Volume 2. Jazzybee Verlag. p. 30. ISBN 978-3-8496-7820-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=EXUtDwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Eastlick, P.. "Argo Navis". http://www.astro.wisc.edu/~dolan/constellations/extra/ArgoNavis.html.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Barentine, John (2015). A History of Obsolete, Extinct, or Forgotten Star Lore. Springer. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-3-319-22795-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=u_7NCgAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Toomer, G.J. (1984). Ptolemy's Almagest. Duckworth & Co. Ltd.. p. 403. ISBN 0715615882. https://isidore.co/calibre/get/pdf/Ptolemy%26%2339%3Bs%20Almagest%20-%20Ptolemy%2C%20Claudius%20%26amp%3B%20Toomer%2C%20G.%20J__5114.pdf.

- ↑ Brown, Robert Jr. (1885). The Phainomena, or the Heavenly Display of Aratos, done into English Verse. Oxford University: Longmans, Green. p. 40.

- ↑ Lacaille, Nicolas-Louis de (1763). Coelum Australe Stelliferum.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Lacaille, N.L. de (1763). Coelum australe stelliferum. H.L. Guerin & L.F. Delatour. pp. 7ff. https://books.google.com/books?id=LIo_AAAAcAAJ&pg=PP7.

- ↑ Herschel, John F. W. (1844). "Further remarks on the revision of the constellations". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 6 (5): 60. doi:10.1093/mnras/6.5.60. Bibcode: 1844MNRAS...6...60H.

- ↑ Russell, Henry Norris (1922). "The New International Symbols for the Constellations". Popular Astronomy 30: 469. Bibcode: 1922PA.....30..469R.

- ↑ Delporte, E. (1930). Delimitation scientifique des constellations (tables et cartes). Cambridge University Press. Bibcode: 1930dsct.book.....D.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Wagman, M. (2003). Lost Stars: Lost, missing, and troublesome stars from the catalogues of Johannes Bayer, Nicholas-Louis de Lacaille, John Flamsteed, and sundry others. McDonald & Woodward Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-939923-78-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=TYLvAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ Ley, Willy (December 1963). "The Names of the Constellations". Galaxy Science Fiction: 90–99. https://archive.org/stream/Galaxy_v22n02_1963-12#page/n46/mode/1up.

- ↑ Scalzi, John (1 May 2008). Rough Guide to the Universe. Rough Guides Limited. ISBN 978-1-84353-800-4. https://archive.org/details/roughguidetouniv0000scal.

- ↑ Kelley, David H.; Milone, Eugene F. (16 February 2011). Exploring Ancient Skies: A survey of ancient and cultural astronomy. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4419-7624-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=ILBuYcGASxcC.

- ↑ Barentine, John C. (2015). The Lost Constellations: A history of obsolete, extinct, or forgotten star lore. Springer. p. 73. ISBN 978-3-319-22795-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=u_7NCgAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Selin, Helaine (6 December 2012). Astronomy Across Cultures: The history of non-western astronomy. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 308. ISBN 978-94-011-4179-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=vRHvCAAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Robertson, Margaret; Po Eung, Eric (June 1, 2016). Everyday Knowledge, Education, and Sustainable Futures: Transdisciplinary approaches in the Asia-Pacific region. Springer. p. 63. ISBN 978-9811002168.

- ↑ Best, Elsdon (July 1903). "Food Products of Tuhoeland: being notes on the food-supplies of non-agricultural tribes of the natives of New Zealand; together with some account of various customs, superstitions, &c., pertaining to foods". Transactions of the Royal Society of New Zealand 35: 78.

- ↑ Maud Worcester Makemson (1941). The Morning Star Rises: An account of Polynesian astronomy. Yale University Press. Bibcode: 1941msra.book.....M. https://books.google.com/books?id=Pj0eAAAAIAAJ.

External links

- Starry Night Photography : Argo Navis Image

- Ian Ridpath's Star Tales – Argo Navis

- Warburg Institute Iconographic Database – Argo (Navis) (medieval and early modern images of Argo Navis)