Astronomy:Mundrabilla (meteorite)

| Mundrabilla | |

|---|---|

Mundrabilla main mass | |

| Type | Iron |

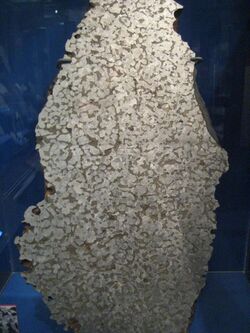

| Structural classification | Medium octahedrite |

| Group | IAB |

| Composition | 65-75% iron-nickel (7.8% Ni, 0.48% Co) |

| Country | Australia |

| Region | Western Australia |

| Coordinates | [ ⚑ ] : 30°47′S 127°33′E / 30.783°S 127.55°E[1] |

| Observed fall | >1 million years[2] |

| Found date | 1911 |

| TKW | 22 tonnes (22 long tons; 24 short tons)[3] |

The Mundrabilla meteorite is an iron meteorite found in 1911 in Australia,[1] one of the largest meteorites found, with a total known weight of 22 tonnes and the main mass (the single largest fragment) accounting for 12.4 tonnes.[3]

History

In 1911 an iron meteorite fragment of 112 g was found by Harry Kent, foreman in charge of camels for the Western Australian survey of the transcontinental railway route, at [ ⚑ ] 31°1′S 127°23′E / 31.017°S 127.383°E, on Premier Downs station on the Nullarbor Plain. The small meteorite was called Premier Downs I. Later in 1911 Kent found another small iron meteorite (116 g) about 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) west from the found location of Premier Downs I, named Premier Downs II. Both meteorites were medium octahedrites, believed to be part of the same fall.[4]

In 1918 a third similar small iron meteorite of 99 g was found in the area by A. Ewing, named Premier Downs III.

In 1962 a small iron meteorite of 108 g with similar characteristics was found near Loongana railway station by a rabbit trapper named Harrison. It was suggested as a possible pairing with the previous Premier Downs samples.[4]

In 1965 three small iron fragments (94.1 g, 45 g, 38.8 g) were found by Bill Crowle of the Geological Survey of Western Australia 16 kilometres (9.9 mi) north of Mundrabilla Siding on the Trans Australian Railway at [ ⚑ ] 30°45′S 127°30′E / 30.75°S 127.5°E.

In April 1966 two very large iron masses of 12.4 tonnes and 5.44 tonnes were found in the Nullarbor Plain at [ ⚑ ] 30°47′S 127°33′E / 30.783°S 127.55°E by geologists R.B. Wilson and A.M. Cooney during a geological survey. The two masses were lying 180 metres (590 ft) apart, in clayey soil within slight depressions. The masses were surrounded by a large number of small iron fragments. The meteorites were named Mundrabilla,[1][4] while the largest fragment, the eleventh largest found in the world (As of 2013), is distinguished as Mundrabilla I.[5][6]

In 1967 a small iron fragment of 66.5 g found at [ ⚑ ] 30°57′S 126°58′E / 30.95°S 126.967°E by Harry Butler, was named Loongana Station West.[4]

It has been suggested that the Mundrabilla meteorites are closely related to the Loongana Station and Premier Downs meteorites, and were shed from the same mass during atmospheric ablation.[7]

Mundrabilla I, the main mass of 12.4 tonnes, is now conserved at the Western Australia Museum.[3][8]

The secondary piece of the Mundrabilla meteorite, weighed at approximately 3.5 tons, was recovered in 1988. It was taken by train from Loongana to Perth where it was studied at the Western Australia Museum. It is now on display at the Museum of the Great Southern in Albany, Western Australia.[9]

Composition

The meteorite is 65-75% iron-nickel, including 35% by volume of troilite (iron sulphide), with inclusions of schreibersite, graphite and silicates, mainly olivine, pyroxene and potassium-rich plagioclase.[4][10][11]

Classification

Mundrabilla is classified as part of the IAB group. The IAB group is often viewed as complex of many different groups. In this complex, Mundrabilla, Waterville, and Buffalo Gap form the "Mundrabilla trio" or "Mundrabilla grouplet" (a group of meteorites with less than 5 members).[12][13] If two more meteorites with similar properties would be found they could form another group within the IAB complex.[14]

Superconductivity

In March 2018 it was reported that evidence of tiny traces of low temperature superconductivity was found in the 12.4 tonne main mass of the Mundrabilla meteorite. The superconductor appeared to be an alloy of indium, tin and possibly lead. This mix was already known as 5 Kelvin superconductor but the find is a scientific breakthrough in other ways. The significance is that the scientists validated their technique for searching for naturally occurring superconductors, and meteorites are a good starting point. 5 Kelvin is -268 Celsius, and the best superconductor to find would work without need for any cooling.[15]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Meteoritical Bulletin Database: Mundrabilla

- ↑ Bevan, Alex (March 1996). "Meteorites recovered from Australia". Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia 78 (1): 38. https://www.rswa.org.au/publications/Journal/79(1)/vol%2079-1(33-42).pdf. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Mundrabilla iron meteorite (main mass 12.4 tonnes)". http://museum.wa.gov.au/research/collections/earth-and-planetary-sciences/meteorite-collection/mundrabilla-iron-meteorite-ma.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 de Laeter, John R.; Cleverly, William H. (31 March 1983). "Further Finds from the Mundrabilla Meteorite Shower". Meteoritics 18 (1): 29–34. doi:10.1111/j.1945-5100.1983.tb00574.x. Bibcode: 1983Metic..18...29D.

- ↑ Schrope, Mark (October 2002). "Meteorite Mystery". NASA Office of Biological and Physical Research. http://spaceresearch.nasa.gov/research_projects/meteorite.html.

- ↑ Classen, Norbert. "The World's Largest Meteorites". http://www.meteoris.de/basics/charts1.html.

- ↑ McCall, Gerald; Cleverly, William (1970). "A review of the meteorite finds on the Nullarbor Plain, Western Australia, including a description of thirteen new finds of stony meteorites". Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia 53: 69–80. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/53483288#page/7/mode/1up. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ↑ Mundrabilla iron meteorite Western Australia Museum

- ↑ Museum of the Great Southern (Residency Road, Albany), A Piece of Mundrabilla Meteorite, leaflet for visitors.

- ↑ Kirsten, Till Arnulf (1973). "Isotope studies in the Mundrabilla iron meteorite". Meteoritics 8: 400. Bibcode: 1973Metic...8..400K.

- ↑ de Laeter, John R. (August 1972). "The Mundrabilla Meteorite Shower". Meteoritics 7 (3): 285–294. doi:10.1111/j.1945-5100.1972.tb00442.x. Bibcode: 1972Metic...7..285D.

- ↑ Buchwald, Vagn F. (1975). The Handbook of Iron Meteorites. University of California. ISBN 9780520029347. https://evols.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/handle/10524/35892/vol3-Wall-Wea(LO).pdf#page=9.

- ↑ "Meteoritical Bulletin: entry for Buffalo Gap". The Meteoritical Society. 2010. https://www.lpi.usra.edu/meteor/metbull.php?code=51831.

- ↑ Wasson, John T.; Kallemeyn, Greg W. (30 June 2002). "The IAB iron-meteorite complex: A group, five subgroups, numerous grouplets, closely related, mainly formed by crystal segregation in rapidly cooling melts". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 66 (13): 2445–2473. doi:10.1016/S0016-7037(02)00848-7. Bibcode: 2002GeCoA..66.2445W.

- ↑ Cho, Adrian (6 March 2018). "Superconducting materials found in meteorites". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aat5142. http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2018/03/superconducting-materials-found-meteorites. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

External links

- Mundrabilla, IMCA Encyclopedia of Meteorites