Biography:Mihai Ralea

Mihai Dumitru Ralea | |

|---|---|

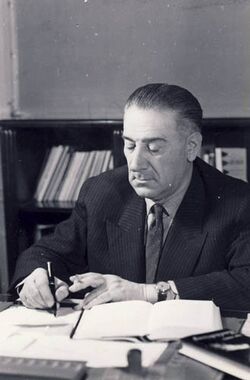

Ralea at his desk, photographed c. 1960 | |

| Born | May 1, 1896 Huși, Kingdom of Romania |

| Died | August 17, 1964 (aged 68) Central Europe (near Prague, Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, or East Berlin, German Democratic Republic) |

| Other names | Mihail Ralea, Michel Raléa, Mihai Rale |

| Academic background | |

| Alma mater | University of Bucharest University of Iași |

| Influences | Henri Bergson, Célestin Bouglé, Émile Durkheim, Friedrich Engels, Paul Fauconnet, Ludwig Gumplowicz, Dimitrie Gusti, Lucien Herr, Garabet Ibrăileanu, Pierre Janet, Jean Jaurès, Ludwig Klages, Vladimir Lenin, Lucien Lévy-Bruhl, André Malraux, Karl Marx, Max Scheler, Werner Sombart, Joseph Stalin |

| Academic work | |

| Era | 20th century |

| School or tradition | |

| Institutions | University of Iași University of Bucharest |

| Main interests | political sociology, sociology of culture, aesthetics, anthropology, social psychology, national psychology, social pedagogy, Marxist sociology, Romanian literature |

| Influenced | Matei Călinescu, Victor Iancu, Adrian Marino (ro), Tatiana Slama-Cazacu, D. I. Suchianu |

| Signature | |

| |

Mihai Dumitru Ralea (also known as Mihail Ralea, Michel Raléa, or Mihai Rale;[1] May 1, 1896 – August 17, 1964) was a Romanian social scientist, cultural journalist, and political figure. He debuted as an affiliate of Poporanism, the left-wing agrarian movement, which he infused with influences from corporatism and Marxism. A distinguished product of French academia, Ralea rejected traditionalism and welcomed cultural modernization, outlining the program for a secular and democratic "peasant state". Mentored by critic Garabet Ibrăileanu, he objected to the Poporanists' cultural conservatism, prioritizing instead Westernization and Francophilia; however, Ralea also mocked the extremes of modernist literature, from a position which advocated "national specificity". This ideology blended into his scholarly work, with noted contributions to political sociology, the sociology of culture, and social and national psychology. He viewed Romanians as naturally skeptical and easy-going, and was himself perceived as flippant; though he was nominally active in experimental psychology, he questioned its scientific assumptions, and preferred an interdisciplinary system guided by intuition and analogies.

Ralea was a professor at the University of Iași and, from 1938, the University of Bucharest. By 1935, he had become a doctrinaire of the National Peasants' Party, managing Viața Românească review and Dreptatea daily. He had publicized polemics with the far-right circles and fascist Iron Guard, which he denounced as alien to the Romanian ethos; Ralea approximated a Poporanist, leftist, take on Romanian nationalism, which he opposed to both fascism and communism. He later drifted apart from the party's centrist leadership and his own democratic ideology, setting up a Socialist Peasants' Party, then embracing authoritarian politics. He was a founding member and Labor Minister of the dictatorial National Renaissance Front, representing its corporatist left-wing. Seeing himself as a social reformer whose talents had been channelled by the Front, Ralea founded the leisure service Muncă și Voe Bună, and later served as the Front's regional leader in Ținutul Mării. He fell from power in 1940, finding himself harassed by successive fascist regimes, and became a "fellow traveler" of the underground Communist Party.

Ralea willingly cooperated with the communists and the Ploughmen's Front before and after their arrival to power, serving as Minister of Arts, Ambassador to the United States, and vice president of the Great National Assembly. His missions coincided with the inauguration of a Romanian communist regime, whose policies he privately feared and resented. His diplomatic mission, tinged in scandal, was cut short by Foreign Minister Ana Pauker; Securitate operatives regarded him as a suspicious opportunist and contact for the Freemasonry, keeping him under close surveillance upon his return. He was sidelined, then recovered, and, as a Marxist humanist, was one of the regime's leading cultural ambassadors by 1960. Heavily controlled by communist censorship, his work gave scientific credentials to the communist rulers' anti-American propaganda, though Ralea also used his position to protect some of those persecuted by the authorities.

Ralea's final contributions assisted in the re-professionalization of Romanian psychology and education, with the retention of a more liberal, de-Stalinized, communist doctrine. A personal friend of the Communist General Secretary, Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, and to secondary figures such as Ion Gheorghe Maurer, he endorsed the regime's transition into national communism. Always an avid traveler and raconteur, he became completely uninterested in scholarly ventures around the age of sixty. He died abroad, while on mission to the UNESCO, and was posthumously diagnosed with a neurological disease. He endures in cultural memory as a controversial figure: celebrated for his sociological and critical insights, he is also reprehended for his nepotism, his political choices, and his literary compromises. He was survived by two daughters, one of whom was Catinca Ralea, who achieved literary fame as a translator of Western literature.

Biography

Early life and Poporanist beginnings

A native of Huși, Fălciu County (currently in Vaslui County), Ralea was the son of a Dumitru Ralea, a local magistrate, and Ecaterina Botezatu-Ralea;[2] the couple also had a daughter, who married the Gagauz politician Dumitru Topciu in 1944.[3] According to historian Camelia Zavarache, Ralea's ethnic background was non-Romanian: on his father's side, he was a Bulgarian, while his mother was Jewish.[4] The family was relatively wealthy, and Dumitru had served as Fălciu representative in the Senate of Romania.[5] His son was always spiritually attached to his native region and, later in life, bought himself a vineyard on Dobrina Hill, just outside Huși, building himself a vacation home.[6] He completed his primary education at Huși (Târgul Făinii) School No 2,[7] before he moved on to the urban center of Iași, where he enlisted at the Boarding High School, studying the classics. He was colleagues with another future sociologist, D. I. Suchianu, with whom he made visits to the café-chantant and planned to write his first book (a French-language study of human intelligence); both men took top honors in their respective class.[8] The two remained personal and political friends for the rest of their lives.[8][9][10] Another enduring friendship was formed on school grounds between Ralea and historian Petre Constantinescu-Iași, who became Ralea's main connection to the revolutionary left.[11]

According to Suchianu, they were avid readers, who quickly went through the popular collections put out by Flammarion, and ended up discovering Marxist literature—mainly through the introductions put out by Charles Gide and Gabriel Deville.[9] Ralea went on to attend the University of Bucharest Faculty of Letters and Philosophy, under Constantin Rădulescu-Motru (who shortlisted and prepared Ralea for academic tenure).[12] He made his debut in publishing during 1916, with an essay in Rădulescu-Motru's Revista de Filozofie,[13] and with Convorbiri Literare articles that he usually signed with the initials M. R. (an alternative signature he would use for the rest of his career).[14] Ralea was university colleagues with philosophers Tudor Vianu and Nicolae Bagdasar, who also joined his circle of intimate friends.[15] Their studies were interrupted by the Romanian Campaign of World War I, during which time Ralea relocated to Iași. He and Suchianu served in the Romanian Land Forces, as part of an artillery battery.[9] Ralea took his final examination in Law and Letters at the University of Iași, in 1918.[2] His professors included the culture critic Garabet Ibrăileanu, who became Ralea's mentor.[16] Ralea recalled that his first encounter with Ibrăileanu was "my life's greatest intellectual event".[17]

Described by Vianu as a "young luminary" with "new and original ideas", "always surrounded by a sizable pack of students",[18] Ralea returned to cultural journalism in postwar Greater Romania. From February 1919, he was a contributor to the Iași-based review Însemnări Literare, which stood in for the temporarily disestablished Viața Românească.[19] The magazine was managed by the novelist Mihail Sadoveanu and heavily influenced by Ibrăileanu. Their friendship sealed Ralea's affiliation to prewar Poporanism, a leftist current which promoted agrarianism, "national specificity", and art with a social mission. The Însemnări Literare group also recognized that Poporanism was made inadequate by the social promises of land reform and universal male suffrage. These policies, Ibrăileanu acknowledged, "settled a debt" with the peasantry.[20] Poporanism was generally pro-Westernization, with a noted reserve; taken separately, Ralea was the most pro-Western, socialist, and least culturally conservative thinker of this category.[21]

Also in 1919, Ralea and his new friend, Andrei Oțetea, earned state scholarships to complete his doctorate in Paris.[22] Ralea entered the École Normale Supérieure as a disciple of Lucien Herr,[13] simultaneously registering for doctoral programs in letters and politics, with interests in sociology and psychology. He studied under the functionalist Célestin Bouglé, then under Paul Fauconnet and Lucien Lévy-Bruhl, and later, at the Collège de France, under Pierre Janet.[23] As he himself recounted, he became a passionate follower of the French Left, a reader of Jean Jaurès, and a guest of Léon Blum's.[24] Young Ralea defined himself as a rationalist, heir to the Age of Enlightenment and the French Revolution ,[24] and was ostensibly an atheist.[25]

Ralea's later friend and disciple psycholinguist, Tatiana Slama-Cazacu, suggests that he was a "salon socialist" who came to rely on his anti-socialist father's fortune so as to maintain his Parisian lifestyle.[26] For a while, he also managed a Romanian restaurant owned by the banker Aristide Blank.[27] His secular agenda was underscored when he joined the Romanian Freemasonry, which, historian Lucian Nastasă writes, implied a commitment to freethought and religious toleration.[28] By 1946, he was an 18° in the Chapter of Rose Croix.[29] He was part of a tight cell of Romanian students in letters or history, which also included Oțetea, Gheorghe Brătianu, and Alexandru Rosetti, who remained close friends over the decades.[30] Suchianu and his sister Ioana, who were also studying in Paris, lived in the same boarding house as Ralea.[31]

Debut as theoretician

With funds raised by a Support Committee that included Ralea,[32] Viața Românească was eventually revived by Ibrăileanu. Ralea became its foreign correspondent, sending in articles about the intellectual life and philosophical doctrines of the Third Republic,[33] and possibly the first Romanian notices about the work of Marcel Proust.[34] He traveled extensively, studying first-hand the cultural life of France, Belgium, Italy, and Weimar Germany.[33] In 1922, Ralea took his Docteur d'État degree (the sixth Romanian to ever qualify for it)[33] with L'idée de la révolution dans les doctrines socialistes ("The Idea of Revolution in Socialist Doctrines"). Under the Francized name Michel Raléa, he published it at Rivière company in 1923. L'idée de la révolution... theorized that, in order to be classified as a revolution, a social movement needed at once a "social body", an "ideal", and a "transfer of power"—depending on which trait was prevailing, revolutions were, respectively, "organic", "programmatic", or "means-based".[35] The focus of his attention was Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, whom he rediscovered (and criticized) as a proponent of "class solidarity" and nonviolent revolution.[36] The work earned Ralea the Institut de France's Prix Osiris (fr)[13] and a Doctor of Letters degree in 1923.[2] He spent another several months frequenting lectures at the University of Berlin.[33] It was there that he first met a future enemy, the poet-mathematician Ion Barbu. The latter left a corrosive record of their first encounter, dismissing Ralea as a "clown" with "aristocratic manias".[37]

Upon his return to Romania, Ralea began publishing his political and sociological essays in reviews such as Fapta, Ideea Europeană, and Gândirea.[38] He was also involved with Dimitrie Gusti and Virgil Madgearu's Romanian Social Institute, publishing his texts in its Arhiva pentru Știință și Reformă Socială. In 1923, it hosted his essay on "The Issue of Societal Classification" and his critical review of German sociology.[39] While still in Paris, Ralea was confident that he would find employment: the University of Iași Chair of Sociology had been set aside for him by Rădulescu-Motru, with Ibrăileanu's approval.[40] The matter was complicated when another Paris graduate, Garabet Aslan, ran for the same position. Supported by Ibrăileanu and Gusti, Ralea was eventually moved to the Logic and Modern Philosophy Department, as an assistant professor to Ion Petrovici, while also employed as lecturer in social pedagogy.[41] According to Ralea's own words, this was a "ridiculous" situation: most of his students were girls, some of whom were infatuated with him.[42] He had married Ioana Suchianu in November 1923, while still in Bucharest, and lived with her in a small apartment above the Viața Românească offices.[43]

For the next two years, Ralea diversified his qualifications with the goal of obtaining employment in his main field. He published the tract Formația ideii de personalitate ("How the Notion of Personality Is Formed"), noted as a pioneering introduction to behavioural genetics.[44] On January 1, 1926, following good referrals from Petrovici (and despite the preference of psychology students, who favored C. Fedeleș), Ralea was appointed Professor of Psychology and Aesthetics at the University of Iași.[45] As noted by historian Adrian Neculau, his victory showed that no one in Iași could stand up to Poporanists' "power strategy".[46] Ralea soon became one of Viața Românească's ideologues and polemicists, as well as architect of its satire column, Miscellanea (alongside Suchianu and, initially, George Topîrceanu).[47] By 1925, he was also regularly featured in the left-wing daily Adevărul, and its cultural supplement, Adevărul Literar și Artistic.[48] His essays were taken up by other cultural magazines throughout Romania, including Kalende of Pitești and Minerva of Iași.[49] In 1927, when Ralea published his Contribuțiuni la știința societății ("Contributions to Social Science") and Introducere în sociologie ("Companion to Sociology"),[50] Gusti's Social Institute had Ralea as a guest speaker, with a lecture on "Social Education".[51] At around that time, with Gusti as president of the Broadcasting Company, Ralea became a frequent presence on the radio.[52]

In his columns and essays, Ralea defended Ibrăileanu's "national specificity" against criticism from the new-wave modernists at Sburătorul. Eugen Lovinescu, the modernist ideologue, had reconnected with 19th-century classical liberalism, rejecting Poporanism as a nationalist, culturally isolationist, and socializing phenomenon. Lovinescu and Ralea denounced each other's politics as reactionary.[53] Ralea opined that Poporanist ideas were still culturally relevant, and not in fact isolationist, since they provided a recipe for "originality"; as he put it, "national specificity" had become inevitable.[54] The conflict was not just political: Ralea also objected to modernist aesthetics, from the pure poetry cultivated by Sburătorul to the more radical Constructivism of Contimporanul magazine.[55]

Ralea was not an anti-modernist, but rather a particular modernist. According to his friend and colleague Octav Botez, he was an "integrally modern man" in tastes and behavior, "one of the few philosophers who conceived of, and lived, their lives as regular people, with a naturalness and facility that were charming and stimulating."[56] The same was also noted by Contimporanul writer Sergiu Dan, who proposed that Ralea denied himself "all sort of transaction with the confuse world of sentiment".[57] Ralea's literary columns very often promoted modernist writers, or modernist interpretations of classical ones, such as when he used Janet's psychology to explain the genesis of works by Thomas Hardy.[58] More famous was his reading of Proust through Henri Bergson's classification of memory.[34][59] Ralea offered much praise to rationalist modernists such as Alexandru A. Philippide, and hailed Tudor Arghezi, the eclectic modernizer of poetic language, as Romania's greatest poet of the day.[60] Ralea (and, before him, Ibrăileanu) campaigned for social realism in prose. His natural favorite was Sadoveanu, but he was also enthusiastic about modernist novels with a flavor of social radicalism, including those by Sburătorul's Hortensia Papadat-Bengescu.[61]

Ralea vs. Gândirea

With the Lovinescu–Ralea debate occupying the center stage at Viața Românească and Sburătorul, a new intellectual movement, critical of both modernism and Poporanism, was emerging in the cultural life of Greater Romania. Led by poet-theologian Nichifor Crainic, this group took over at Gândirea, turning the magazine against its former Viața Românească allies.[62] As pointed out by Lovinescu, Ralea was initially welcoming of Crainic's "remarkable" program.[63] He did not object to Crainic's Romanian Orthodox devotion (seeing it as compatible with secularism and "national specificity"), but mainly to his national conservatism, which worshiped the historical past.[64] Like other Poporanists, Ralea adopted left-wing nationalism, arguing that the very concept of nation was a product of French radicalism: "[It] emerged from the great French Revolution, the modest ideology of the bourgeoisie. [...] What's more, we may claim that only a democracy can truly be nationalistic."[65] He credited the core ideas of Romanian liberalism, according to which Romanian national awareness was an afterthought of Jacobinism: "We have had to visit France to find out we're Romanians."[66] As noted by scholar Balázs Trencsényi: "Ralea sought to separate the study of national specificity, which he considered to be legitimate, from the exhortation of national particulars, which he rejected."[67]

In 1928, Gândirea hosted the inflammatory "White Lily" Manifesto. It signaled the Poporanists' confrontation with a "new generation" of anti-rationalists, and Ralea's personal rivalry with one of the White Lily intellectuals, Petre Pandrea (ro).[68] Pandrea's Manifesto was at once a plea for aestheticism and mysticism, a critique of "that famed social justice" idea, and an explicit denunciation of Ralea, Ibrăileanu, Suchianu and the Sburătorul group as "dry", "barren", all too critical.[69] Ralea answered with half-satirical comments: the country, he noted, could do without "prophets" with "fun and interesting biases", but not without "liberty, paved roads, justice and cleanliness in the streets".[70] In his view, the Manifesto authors were modern-day Rasputins, prone to fanatical vandalism.[71]

From that moment on, Crainic's Orthodox spirituality and traditionalism made a slow transition into far-right politics. Their rejection of democracy became another issue of dispute, with Ralea noting, in 1930, that "all civilized countries are democratic; all semi-civilized or primitive countries are dictatorial."[72] Over the years, Gândirists produced more and more systematic attacks on Ralea's ideology, condemning its atheism, "historical materialism", and Francophilia.[73] In reply, Ralea noted that, beyond their facade, national and religious conservatism meant a reinstatement of primitive customs, obscurantism, Neoplatonism, and Byzantinism.[74] He pushed the envelope by demanding a program of forced Westernization and secularization, to mirror Kemalism.[75]

His comments also challenged the grounding of Gândirist theory: Romanian Orthodoxy, he noted, was part of an international Orthodox phenomenon that mainly included Slavs, whereas many Romanians were Greek-Catholic. He concluded, therefore, that Orthodoxy could never claim synonymy with the Romanian ethos.[76] Ralea also insisted that, despite its nativist anti-Western claims, Orthodox religiousness was a modern "trifle", that owed inspiration to Keyserling's Theosophy and Cocteau's Catholicism.[77] He maintained that Romanian peasants, whose religiousness was exhorted by Crainic, were "superstitious, but atheistic", not respectful "of any spiritual value when it should compete with their logical instincts." No other people, he contented, was as blasphemous as Romanians when it came to profanities.[78]

Ralea collected his critical essays as a set of volumes: Comentarii și sugestii ("Comments and Suggestions"), Interpretări ("Interpretations"), Perspective ("Perspectives").[79] He was still involved in psychological research, with tracts such as Problema inconștientului ("The Problem of the Unconscious Mind") and Ipoteze și precizări privind știința sufletului ("Hypotheses and Précis Regarding Spiritual Science").[80] Ralea also resumed his European travels, touring the Kingdom of Spain, and was unenthusiastic about its conservatism. Ralea's travelogue, Memorial din Spania, depicts the country as a reactionary bulwark of "somber priests" and "festooned soldiers".[57] Another Memorial, serialized by Adevărul Literar și Artistic, detailed his trips through Germanic-speaking Europe.[81]

PNȚ deputy and Viața Românească editor

Shortly before the election of December 1928, Ralea was attracted into the National Peasants' Party (PNȚ), speaking out against the National Liberal political class as "an abnormal regime of corruption and brutality."[82] He successfully contested a seat in the Assembly of Deputies, and was reelected in 1933; during that interval, he also presided upon Fălciu's party chapter.[83] Ralea was one of a compact group of National Peasantist academics in Poporanist Iași, together with Botez, Oțetea, Constantin Balmuș, Iorgu Iordan, Petre Andrei, Traian Bratu, and Traian Ionașcu.[84] Inside the party, Ralea was a follower of the Poporanist founding figure, Constantin Stere, but did not follow Stere's "Democratic Peasantist" dissidence of 1930.[85] Around 1929, Ralea was a noted contributor to the party press organ Acțiunea Țărănistă and to Teodorescu-Braniște's Revista Politică.[86] In January 1933, Ibrăileanu retired, leaving Ralea and literary critic George Călinescu as editors of Viața Românească.[87]

Ralea eventually affiliated with the centrist current of the PNȚ, distancing himself from those party factions who were tempted by socialism.[88] Ralea and Ibrăileanu still promoted the vision of a "peasant state", accepting socialist reformism, but still cautious of socialist industrialization, and rejected outright the idea of proletarian primacy. Criticized by the communist left as "outstanding shortsightedness",[89] this ideological position came to define the PNȚ in the mid-1930s. Ralea defended classical parliamentarianism at several Inter-Parliamentary Union meetings, including the 1933 conference in the Republic of Spain, but insisted on the benefits of statism and a planned economy.[90]

By then, Ralea was leaving behind his sociological research. As noted by his friend Botez, he was "absent-minded and preoccupied most of all with politics."[91] Botez noted that Ralea was showing signs of hyperactivity, seemingly incapable of concentrating during formal functions.[42] He became infamous as one of the "traveling professors",[92] who lived in Bucharest and only taught the minimum of classes allowed in Iași—one of his return trips to Iași, in 1936, was for the funeral ceremony of his mentor Ibrăileanu.[93] He now owned an Iași townhouse and a villa in Bucharest's Filipescu Park.[94] Although lovingly married to Ioana, he had begun an affair with another woman, Mariana Simionescu[95] (credited in some sources as Marcela).[96]

Ralea's energies were also drawn into administrative disputes and professional rivalries. Alongside Brătianu, he fought to obtain Oțetea a permanent seat at the University of Iași, at the expense of PNȚ colleague Ioan Hudiță.[97] He tried to do the same for Rosetti, but was met with the stiff opposition of linguist Giorge Pascu.[98] Hudiță was particularly vexed by these maneuvers, and, in 1934, asked for a formal inquiry by Parliament, and even for a formal review of Ralea's own 1926 appointment.[99] More privately, Hudiță also claimed that Ralea was having affairs with his female students, and even with younger girls who presented to Ralea for their baccalaureate examination.[96] Such criticism did not dissuade Ralea. In 1937, he also managed to obtain an Iași University chair for Călinescu, in controversial circumstances.[100]

From 1934 to March 1938,[101] Ralea was also editor of the main PNȚ newspaper, Dreptatea. He contributed its political editorials, answering to criticism from the right. In February 1935, he co-authored and published the new PNȚ Party Program, which rendered explicit the goal of transforming Romania into a "peasant state".[102] In Dreptatea, addressing Universul editor Pamfil Șeicaru, Ralea dismissed suspicions that the "peasant state" signified a "simplistic domination" or a dictatorship of the peasantry. He maintained that the notion simply implied "a juster distribution of the national income", and the "collective" but peaceful "redemption of an entire class."[103]

Against the Iron Guard

Ralea's time at Dreptatea overlapped with the emergence of fascism, whose leading Romanian representatives were members of the Iron Guard. This violent movement had been temporarily banned in 1931, by order of a PNȚ Interior Minister, Ion Mihalache. Mihalache's ban followed repeated requests by the party's left-wingers, Ralea included.[104] Ralea had his own brush with the Guard in late 1932, when he was presiding upon symposiums on French literature at Criterion society. One of the sessions, focusing on André Gide, was interrupted, on Crainic's instigation, by Guardsmen under Mihai Stelescu, who assaulted Criterion activists and created a bustle.[105] By 1933, Ralea had quarreled with the Criterion cell, which had since adopted "new generation" idealism and sympathy for the Iron Guard.[106] In private, he also dismissed the Guard's new convert and ideologue, Nae Ionescu, as a "trickster" and a "barber".[107]

The issue of Romanian fascism became stringent after the Guard assassinated Romanian Premier Ion G. Duca. In his articles, Ralea described the National Liberal administration as "insane and degenerate" for continuing to tolerate the Guard's existence, instead of jailing its leaders.[108] At Dreptatea, protesting against the Guard's assault of the leftist intellectual Alexandru Graur, Ralea decried fascism in Romania as an "island of Doctor Moreau", an experiment in the growth of "blind and absurd mysticism".[109] As a sociologist, Ralea also participated in public debates on the "Jewish Question" in Romania. During February 1934, Hasmonaea club and Rădulescu-Motru co-hosted a topical conference, with Ralea as a guest—alongside Henric Streitman (who spoke about Judaism) and Sami Singer (who outlined issues pertaining to Zionism).[110]

In 1935, 161 of Ralea's essays were collected and published at Editura Fundațiilor Regale as Valori ("Values"). They predicted the emergence of a stable civilization, conformist and collectivist, whose great merit was the elimination of careerism.[111] Ralea synthesized his critique of fascism in the 1935 essays on "The Right's Doctrine", taken up by Dreptatea and Viața Românească. These texts described the far-right and fascism as parasitical phenomena, feeding on democracy's errors, with an ignorant mindset, incapable of subtlety.[112] His assessments were countercriticized by Guardist intellectual Toma Vlădescu, in the newspaper Porunca Vremii. According to Vlădescu, the "right-wing ideology" existed as an expression of the "human equilibrium", and, at its very core, was antisemitic.[113]

With the advent of Nazi Germany and the invigoration of European fascism, Ralea was again moving to the left, cooperating with the Social Democratic Party (PSDR). In 1936, at Dreptatea, he condemned the German march into Rhineland as a bad omen and an attack on world peace.[114] He became one of the PNȚ men affiliated with Lord Cecil's International Peace Campaign, which, in Romania, was dominated by PSDR militants.[115] He also had rapports with the outlawed Romanian Communist Party (PCdR): with Dem I. Dobrescu, he formed a committee to defend jailed communists such as Alexandru Drăghici and Teodor Bugnariu.[116]

In 1937, with an obituary piece to the "martyr" Stere, Ralea defended Poporanism from accusations of "Bolshevik" subservience. Bolshevism, he argued, was impossible in Romania.[117] However, he had a working relationship with the PCdR, whose leaders were also interested in other PNȚ antifascists (one of them was the White Lily's Pandrea, who had since joined the National Peasantist left current).[118] Around 1937, Viața Românească's editorial panel was joined by dramatist Mihail Sebastian and poet Dumitru Corbea. As recalled by the latter, Suchianu and engaged Ralea had "[editorial] disputes of the most heated kind."[119] Ralea also allowed PCdR intellectuals such as Ștefan Voicu and Lucrețiu Pătrășcanu to publish essays in Viața Românească, and hosted news about social life and culture in the Soviet Union.[120] At the time, the PCdR acknowledged him as one of the intellectuals who could be trusted with "fulfilling the bourgeois revolution in Romania."[121] Overall, Suchianu reports, "all communist intellectuals, or intellectuals who sympathized with [the PCdR], were permanent contributors."[122]

In January 1937, at the PNȚ Youth Conference in Cluj, Ralea spoke of the "peasant state" as a "neo-nationalist" application of democratic socialism, opposed to fascism, and in natural solidarity with the trade unions. He felt confident that this alliance would be powerful enough to outweigh fashionable totalitarianism.[123] In March, he spoke at an all-peasant rally in Ilfov County, whose purpose was to show that the PNȚ had not lost its core electorate.[124] During April, Ralea and his Iași colleagues expressed public solidarity with his old Poporanist friend Sadoveanu, whose books were being burned by far-right militants.[125] Ralea's own sociological work was falling under Guardist scrutiny: in December, Buna Vestire hosted a piece by Horia Stamatu, which referred to Ralea's contribution as "unhinged", and to Ralea personally as "kike-turned", "at odds with the new man".[126]

Becoming Carol's minister

The December 1937 election toned down Ralea's anti-Guard militancy: the PNȚ had a non-aggression pact with the Guardsmen. Consequently, Ralea campaigned in his native Fălciu County alongside the movement's candidates, in terms he would later describe as "cordial".[127] His apparent compromise with the Guard is one of the most serious charges in Pandrea's later criticism of Ralea.[85] The tied elections, and the successes of the Guard, prompted the authoritarian King Carol II to increase his participation in politics, beyond his royal prerogative. Identified as one of the PNȚ "turncoats",[128] Ralea sealed a surprising deal with Carol II and Premier Miron Cristea (the Patriarch of Romania), becoming the country's Minister of Labor. He was promptly stripped of his PNȚ membership, and inaugurated his own party, the exceedingly minor Socialist Peasants' Party (PSȚ).[129] By October 1938, he was working on a project to fuse all of Romania's professional organizations into a general union—the basis for a corporatist reorganization of society.[130]

Historians tend to describe Ralea's attitude toward Carol as "servile",[131] and Ralea himself as Carol's "pocket Socialist"[132] or "intellectual trophy".[133] Ralea himself claimed that the king cultivated his friendship as a likable "communist", though, as Camelia Zavarache argues, there is no secondary proof to attest that Ralea was ever part of Carol's camarilla.[134] Schoolteacher and communist sympathizer Mihail I. Dragomirescu, who met Ralea at this stage, later claimed that Ralea was pushed into collaboration with Carol by their shared "anti-Guardism";[95] by contrast, Iuliu Maniu, the PNȚ chief and leader of the semi-clandestine democratic opposition, suggested that Ralea had "not a trace of character" to complement his intellectual gifts.[129] At the time, PNȚ activists began collecting evidence that Ralea was not an ethnic Romanian, which meant that he could no longer hold public office under the Romanianization laws.[135] Ralea himself was involved in the Romanianization campaign: in late 1938, he accepted Wilhelm Filderman's proposal for the mass emigration of Romanian Jews.[136]

In December 1938, Ralea became a founding member of Carol's single party, the National Renaissance Front (FRN)—joining its 24-member Directorate in January 1939.[137] During that interval, he was participating in a propaganda tour which, according to historian Petre Țurlea (ro), was consuming enough "to make it seem like the Government was on a break, like nothing was being worked on".[138] The establishment offered Ralea several honors, including a reprint of his works by the ministry press.[139] In addition to his ministerial appointment, Ralea became Royal Resident, or governor, of Ținutul Prut, a new administrative region incorporating parts of Western Moldavia and Bessarabia.[140] He was created a Knight 2nd Class of the Order of Cultural Merit (Romania) (ro),[141] publishing, at Editura Fundațiilor Regale, the volume Psihologie și vieață ("Psychology and Life").[80] Toward the end of 1938, Ralea moved from his old chair at the University of Iași and took up a similar position at his Bucharest alma mater.[142] Vianu was the assistant professor, lecturing in specialized aesthetics and literary criticism, and in practice taking over all of Ralea's classes.[143]

Historian Lucian Boia argues: "Of all the king's dictatorship dignitaries, one may count Mihai Ralea as the most left-wing."[144] In Ralea's own view, the FRN regime was, overall, progressive: "I had inaugurated a corpus of social reforms that were approved by the working class."[145] As noted in 1945 by political scientist Hugh Seton-Watson, there was a cynical side to Ralea's reform-mindedness: "however much [the average Romanian intellectual] cursed the regime, he was grateful to it for one thing. It stood between him and the great, dirty, primitive, disinherited masses, whose 'Bolshevik' desire for Social Justice threatened his comforts."[146] Ralea was relatively popular when compared to other FRN officials, a fact noted by the Front leadership during the single-list elections of June 1939, when Ralea was known as the only likable candidate in Ținutul Prut.[147] His time in office brought the creation of a workers' leisure service, Muncă și Voe Bună, together with a Workers' University,[148] a workers' theater, and a hostel for vacationing writers (Casa Scriitorilor).[149] Nepotistic in his selection of a ministerial staff,[150] by November 1939 his ministry was able to co-opt PSDR politicians such as George Grigorovici[151] and Stavri Cunescu.[148][152] He appropriated socialist propaganda, and attracted more or less sizable contributions from various centrists and left-wingers: Sadoveanu, Vianu, Suchianu, Philippide, as well as Demostene Botez, Octav Livezeanu (ro), Victor Ion Popa, Gala Galaction, Barbu Lăzăreanu, and Ion Pas.[153]

Ralea's mandate was also a crossover of left-wing corporatism and fascism. In June 1938, he even visited Nazi Germany and had a formal meeting with his counterpart, Robert Ley.[144][154] His Muncă și Voe Bună was directly inspired by Strength Through Joy and the Opera Nazionale Dopolavoro.[46][148][154][155] In 1939, Ralea celebrated May Day with a large parade of support for Carol II. This was meant to undermine the leftist Workers' Day while showing the success of the FRN's worker guilds, and was partly inspired by Nazi festivities.[152] Nevertheless, the parade was voluntarily joined by militants of the underground PCdR, who found that it gave them an opportunity for chanting "democratic slogans".[152] In underground PSDR circles, as well as in inside the ministerial structures, rumors spread that Ralea was using secret funds at his discretion to sponsor various PCdR militants, including his schoolmate Petre Constantinescu-Iași; these stories were partly confirmed by Ralea himself.[156]

From March 1939, the premiership had passed to Armand Călinescu, a former PNȚ politician. Ralea was his friend and confidant, and, as he later claimed, defended Călinescu against the "mythomaniacal" Iron Guard.[157] The FRN regime soon organized a massive clampdown of the Guard. Ralea claimed to have protected Guardsmen employed by the Labor Ministry, and to have negotiated pardons for militants interned at Miercurea Ciuc.[158] He obtained one such reprieve for Guardist historian P. P. Panaitescu.[159] Himself a Guard sympathizer, Ion Barbu later claimed that Ralea was behind his marginalization in academia.[160] Ralea was also accused by Pandrea of having done nothing to prevent the arrest of his former Dreptatea colleague, the anti-Carol PNȚ-ist Madgearu.[85] On September 21, 1939, following a spree of extrajudicial killings ordered by government, an Iron Guard death squad took its revenge, assassinating Premier Călinescu. Ralea, Andrei, and other former PNȚ-ists preserved their governmental posts as the premiership passed to Constantin Argetoianu, then to Gheorghe Tătărescu.[161]

Downfall and harassment

Meanwhile, the outbreak of World War II caught Romania isolated from either the Axis Powers and the Western Allies. During the Battle of France, the FRN regime itself was divided between partisans of a détente with Germany and Francophiles such as Ralea. As witnessed by the Swiss diplomat René de Weck, Ralea was restating his Valori ethos at cabinet meetings, in front of Axis representatives, declaring that the Allies stood for "humanistic civilization".[157] Former PCdR activists still enjoyed access to Ralea, through Constantinescu-Iași. In May 1940, the latter tried to create a bridge of communications between the Labor Minister and the Soviet Union.[162] Various reports on both sides confirm that Ralea was in permanent contact with Soviet diplomats, arranged for him by Constantinescu-Iași and Belu Zilber.[163] Ralea was still being given new responsibilities within the FRN structure. That same month, after a complicated selection process, he became president of its regional chapter in Ținutul Mării.[164]

Just a month later, the Soviets issued an ultimatum, demanding that Romania cede Bessarabia. During the deliberations, Ralea voted in favor of Argetoianu's proposal: withdrawing from the region and mobilizing the army on the Prut, in preparation of a future defense.[165] The subsequent occupation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina sent Romania into a deep political crisis. The events, and revelations about the existence of a Nazi–Soviet agreement, led Carol to order a final clampdown of the PCdR's remaining Romanian cells. In July, Ralea intervened to rescue a communist friend, the journalist George Ivașcu.[166]

The Romanian crisis was aggravated in August, when the Nazi-inspired Vienna arbitration stripped her of Northern Transylvania. The political standstill propelled the Iron Guard, which was Nazi-aligned, into government, and forced Carol into permanent exile. The emerging "National Legionary State" banned reviews such as Viața Românească,[167] and moved to prosecute all former FRN dignitaries. The country's new Conducător, General Ion Antonescu, announced early on that he would audit Ralea's estate—news of which were warmly received by the PNȚ.[168] With Panaitescu as the new Rector, the university instituted a Commission for Review, which included Iron Guard sociologist Traian Herseni and eugenicist Iordache Făcăoaru.[169] Of those professors brought before the commission, Ralea was the only one to have his contract terminated without the possibility of transfer.[170] Panaitescu, Herseni and Făcăoaru found that his appointment to Bucharest had been illegal, and dismissed his scientific contributions as having "zero value".[171] Ralea and his colleagues were able to defend Vianu, who was openly Jewish, and who was threatened with demotion under the racial purity laws.[172]

Withdrawing to Huși, Ralea became the target of surveillance by agents of the Siguranța, who monitored his subversive conversations, including his wager that Guard rule would be short-lived.[135] In November 1940, the Guard's Police chief, Ștefan Zăvoianu, ordered the arrests of several FRN dignitaries, Ralea included. This angered Antonescu, who freed Ralea and the others, ordering Zăvoianu to resign.[173] In later years, Ralea confided to his friends that he was sure he would be killed on that night, and that it was in fact Herseni who had pleaded for his release.[174] During the clashes of January 1941, the Iron Guard was ousted, and Antonescu remained unchallenged. The events saw Guardists occupying Ralea's Bucharest residence, and army tanks being used to clear them out of it.[175]

Although fascist, the new regime reinstated Ralea to his professorship. Antonescu castigated the Commission for Review as a "shame", and declared Ralea to be "indispensable".[176] In a companion to Romanian philosophy, published that year, Herseni revised his stance, calling Ralea "a thinker of unquestionable talent", whose sociological work had been "a true revelation."[177] Ralea returned to teach at the university where, in addition to Vianu, he had received as his assistant a refugee from Soviet-occupied territory, Traian Chelariu;[178] meanwhile, Panaitescu was stripped of his position and briefly imprisoned.[179] Still present in public life after the Romania's entry into the anti-Soviet war, Ralea returned to publishing with articles in Revista Română[46][180] and the 1942 book Înțelesuri ("Meanings").[80] Despite being partly recovered by the new regime, and allegedly proposing to Antonescu that they revive together the National Socialist Party,[154] Ralea was still under Siguranța watch, and also spied on by the Police and the German Embassy.[181] His file contains a denunciation of his entire career and loyalties: he stood accused of having been a "socialist-communist" camouflaged within the PNȚ, of having revived the guilds so as to give the PCdR room for maneuver, and of having sponsored Soviet agents to protect himself in the event of a Soviet invasion.[182]

One Siguranța record suggests that, in secret, Ralea was hoping to consolidate a left-wing opposition movement against Antonescu during the early months of 1941. More alarmingly for the regime, Ralea had also begun cultivating a revolutionary and pro-Allied youth, through a new magazine called Graiul Nostru and with British funds.[183] In February, Ralea was subjected to formal interrogations over his contacts with the PCdR under Carol. He defended these, arguing that he had aimed at securing a protective deal between Romania and the Soviets, and that Carol had approved of his effort. The explanation was viewed as plausible by police, and Ralea was allowed to go free.[184] Nevertheless, the file was reopened by August, after revelations that Ralea had cultivated communists since at least the 1930s.[185] In December 1942, Antonescu ordered Ralea's internment at the Târgu Jiu camp.[186] He was held there for about three months, to March 1943, and apparently enjoyed a mild detention regime, with visitations.[187]

Antihitlerite Front

Ralea's return from camp coincided roughly with the Battle of Stalingrad and the turn of fortunes on the eastern front. He soon established contacts with the antifascist opposition, repeatedly seeking to set up a Peasantist left and rejoin the PNȚ. Maniu received him and listened to his pleas, but denied him readmission and invited him to create his own coalition from shards of the Renaissance Front, promising him some measure of leniency "for that hour when we shall be evaluating the past mistakes that have thrown this country into dejection."[129] Their separation remained "unbridgeable";[188] eventually, Ralea reestablished the PSȚ, and attracted into its ranks a Social Democratic dissident faction, led by former PSDR theoretician Lothar Rădăceanu.[189] The two reestablished contacts with the PCdR and other fringe parties: moving between Bucharest and Sinaia (where he owned a villa on Cumpătul Street),[95] Ralea was involved in trilateral talks between the communists, the Ploughmen's Front of Petru Groza, and the National Liberal inner faction of Gheorghe Tătărescu, helping to coordinate actions between them.[190] In Brașov, he met with the economist Victor Jinga, whose antifascist and socialist program was reused in later PSȚ propaganda.[191] Together with party colleague Stanciu Stoian, he signed the PSȚ's adherence to the PCdR's clandestine "Patriotic Antihitlerite Front".[192]

In addition to such underground work, Ralea was notably involved in combating the nationalism and racism of the Antonescu years. He was one of several literary critics who publicly chided a colleague, George Călinescu, for publishing a 1941 treatise which included racialist profiles of Romanian writers,[193] alongside criticism of Ralea's own anti-nationalism.[75] With the 1943 collection of essays, Între două lumi ("Between Two Worlds", published at Cartea Românească),[80] Ralea revised his earlier prophecies about the triumph of collectivism.[194]

Evidence of Ralea's participation in subversion was disregarded by government: in June 1943, when the German Foreign Ministry nominated Ralea as a high-risk target, Antonescu personally replied that this was not the case.[187] In November, Ralea applied for a new Chair of Psychology at Bucharest, reserving his old department for Vianu. The review committee, overseen by leftist allies such as Gusti and Mircea Florian, gave him immediate approval for transfer.[195] His inaugural lecture saw him being publicly applauded by his new students.[196] In February of the next year, Ralea and N. Bagdasar rejected the application of Constantin Noica, the traditionalist philosopher, to join the university teaching staff. In his report, Ralea noted that Noica had "an absolute and metaphysical mindset", with no "practical reason", and that he was therefore unsuited for research and teaching.[197] He also appeared as a defense witness for Gheorghe Vlădescu-Răcoasa, an activist of the underground Union of Patriots.[198] Together with Hudiță and other rival PNȚ-ists, and his friends in Iași academia, Ralea signed to Grigore T. Popa's manifesto of the intellectuals, demanding that Antonescu negotiate a separate peace with the Soviets. Reputedly, the document had been stripped of references to the prosecution of FRN and Antonescian officials, leading Maniu to conclude that the signers were "cowardly".[199]

According to Hudiță, Ralea objected to the Soviets' offer of an armistice as "too soft" on Romania.[199] Blocked out of the National Democratic Bloc coalition,[129][200] which included the PNȚ, the PSDR, and ultimately the PCdR, Ralea watched from the side as the August 23 Coup deposed Antonescu and pushed Romania into the anti-Nazi camp. In case of failure, he had been instructed to leave Sinaia and join a backup provisional government in northern Oltenia.[95] His friend and PSȚ colleague, Grigore Geamănu, was more directly involved in the coup, helping PCdR leader Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej to escape from Târgu Jiu camp and join the other conspirators.[201] In the PSȚ newspaper, Dezrobirea, Ralea saluted "the full triumph of the ideas and principles for which our foremost activists have been militating uninterruptedly these past six years" (a pedigree which seemingly included Ralea's own activities under King Carol).[202] He reissued Viața Românească with a similar statement about "the present triumph of our credo".[203] Meanwhile, keeping up with his earlier threats, Maniu repeatedly asked for Ralea to be indicted for war crimes.[152]

Ralea played an instrumental part in the gradual installation of communism, and is described by various authors as the prototype "fellow traveler".[154][204] In December 1944, he was announced as the Literary Section Vice President of the Romanian Society for Friendship with the Soviet Union (ARLUS).[205] His position as a cultural policymaker was recognized by the moderate liberal Victor Iancu, of the Sibiu Literary Circle. One of Iancu's essays, published by the Circle in January 1945, indicated that Ralea had always been right to highlight the social function of "aesthetic thinking", and as such had provided templates for a "moral therapy for this age".[206] Ralea's PSȚ was drawn into the National Democratic Front (FND) coalition, which comprised the PCdR, the Ploughmen's Front, and the Union of Patriots. According to the PCdR, this transformation of the Antihitlerite Front was "a progressive step, befitting the tasks of the people's revolution";[207] according to historian Adrian Cioroianu, it was more of an opportunistic move on Ralea's part.[208] In private, Ralea claimed that his alignment with the communists helped him provide for his large family, including former landowners, but his account is viewed as doubtful by Zavarache.[209]

Ralea's Socialist Peasantists were eventually absorbed into the Ploughmen's Front. As noted by Zavarache, Ralea now understood that his influence on political life was "exceedingly minor", aware that Groza himself was merely a communist "puppet"; "consequently, he sought to preserve those offices which could ensure him a comfortable lifestyle".[210] Like the rest of the FND, Ralea participated in the movement to depose the monarchist premier, General Nicolae Rădescu. Faced with the PCdR's obstructionism, Rădescu approached Ralea with an alternative offer: the Ploughmen's Front was to form a new government with no communist ministers. Ralea divulged this offer to the Soviet envoy, Andrey Vyshinsky.[211] On February 16, 1945, together with 10 other academics (among them Balmuș, Parhon, Rosetti and Oțetea), he signed a letter of protest, accusing Rădescu of stalling land reform and of undermining the work of the Allied Commission.[212]

Arts Minister and ambassador

Bloody clashes ensued in Bucharest, most of them between anticommunists and communist agents.[212] They signaled a new political crisis, and forced the FND into power. Ralea was made Minister of Arts on March 6, 1945, when Groza took the premiership from the deposed General Rădescu.[213] In June 1945 Ralea was one of the rapporteurs at the Ploughmen's Front largest-ever General Congress.[214] On March 6, 1946, he also took over the Ministry of Religious Affairs, replacing the disgraced Constantin Burducea until August (when Groza himself replaced him in this function).[215]

Ralea became one of several intellectuals who were mobilized to run on the Ploughmen's Front (and FND) list in the 1946 parliamentary election;[216] he headlined the list for Fălciu.[217] In his capacity as minister, Ralea set in motion the purge of PNȚ-ist functionaries and of artists perceived by the PCdR as pro-fascist.[218] In November 1945, he and Grigore Preoteasa reportedly published a forged issue of Ardealul newspaper, as part of an effort to prevent the PNȚ from rallying protests against Groza.[219] Around the same time, Ralea extended his personal protection to Șerban Cioculescu, who became Iași University professor in 1946 upon his intervention.[220] Ralea also pursued his projects for workers' education, authorizing the establishment of a workers' theatrical troupe, Teatrul Muncitoresc CFR Giulești.[221] As a side project, he republished his 1930s travel accounts, completed with notes from his trip to Egypt, as Nord-Sud ("North-South").[95][222]

In September 1946, Ralea stepped down from the Ministry of Arts, only to be appointed Ambassador to the United States. Reputedly, he was a last minute replacement for the Union of Patriots' Dumitru Bagdasar. The latter had fallen severely ill,[223] but was also seen as a political liability by the American side—Ralea, as a former monarchist, was preferable.[224] According to researcher Diana Mandache, Foreign Minister Ana Pauker sensed that Ralea could reach out to, and placate, the international Freemasonry, while at the same time pushing ahead with a leftist takeover of the local Masonic Lodges.[225]

Ralea's own arrival in Washington was delayed by his inclusion on the Romanian delegation to the Paris Peace Conference, and he finally landed on American soil in October.[226] He supported a détente in Romanian–American relations, after President Harry S. Truman had refused to recognize the Groza cabinet. In front of American criticism, he played down the electoral fraud of 1946, claiming that it was within the "normal" boundaries, at some 5% of the vote.[227] Ralea was also tasked with undermining the reputation of the anticommunist opposition and with popularizing communism among Romanian American exiles.[228] The anticommunist press responded by calling Ralea "a liaison man" of the Politburo, tasked with planting Stalinism in America.[229]

Among expatriate Romanians, Ralea and his legation staff had difficulties convincing Maruca and George Enescu, but persuaded Dimitrie Gusti to return to Bucharest.[230] Ralea also approached the former backers of Carol's regime. He built a connection with the industrialist Nicolae Malaxa, but found vocal adversaries in Max Auschnitt and Richard Franasovici.[231] In 1948, Alan R. McCracken from the Office of Special Operations argued that Ralea was Malaxa's political client, and had tipped Malaxa off about the planned nationalization of his industrial concern back in Romania.[232] Going against Soviet policies and his own government, Ralea also sought to obtain American foreign aid, and even political interventions. His persistence in this regard contributed to the relief effort organized by General Schuyler in famine-stricken Western Moldavia.[223]

American assistance fell below Ralea's expectations, owing to various factors, one of which was American suspicion that Groza was diverting food to relieve the Soviet famine; meanwhile, diaspora voices repeatedly argued that Ralea was playing down the scale of famine, and also insinuated that he was embezzling funds.[233] When it transpired that Ralea was genuinely mistrusted by his American contacts, Groza reportedly asked another psychologist, the American-trained Nicolae Mărgineanu, to intervene directly and mend the relationship.[46] In his reports to Bucharest, Ralea complained that: "America's attitude toward us was oscillating between hostility and ignorance. All doors were closed. [...] We were seen as a Soviet branch office, and people were discouraged from giving us any sort of assistance."[234] Reportedly, he was shocked by Truman's ignorance of Romanian affairs.[235] Ralea's diplomatic mission was also tainted by his difficult lifestyle, including his noticeable hypochondriasis,[236] but also his philandering. Ralea had appointed his mistress as cultural attaché, but she deserted her post and left to Mexico while Ioana Ralea took up residence in the Romanian embassy.[237]

With the looming threat of Soviet-style collectivization, Ralea informed the Americans that Romanian peasants valued individual property.[238] Reportedly, during his January 1947 interview with US Secretary of State James F. Byrnes, he pleaded emotionally for Romanians not to be left "behind the Iron Curtain".[239] He was still the country's ambassador when King Michael I was forced to abdicate by the PCdR officials and a communized people's republic was proclaimed. Nevertheless, Pauker greatly reduced his influence in Washington, transferring many of his attributes to Preoteasa.[210] In June, Ralea also became chairman of a Romanian Institute for Foreign Cultural Relations, which was dedicated to the spread of propaganda.[240] He also acted as a sponsor and liaison for Harry Făinaru, who was running a propaganda cell (and alleged spy ring) from Detroit.[241]

Communist marginalization and recovery

A scandal erupted in July 1948, when the Raleas were denied access to the diplomats' beach in Newport, having been blacklisted as "communists". Ioana Ralea endangered her husband's position by protesting against this qualifier; at home, rumor spread that the couple was planning to defect.[242] Ralea was able to persuade Pauker not to recall him, and even organized a reception in her honor during October 1948;[243] he also organized a communist counter-manifestation upon Michael's arrival to Washington.[244] As he confessed to Dragomirescu, he postponed returning to Romania because feared for his safety: Ralea had been told that Gheorghiu-Dej, his personal friend, was no longer in control of the Communist Party, having been branded a Titoist by Joseph Stalin (both rumors were false).[95] While still abroad, Ralea had run in the formal election of March 1948, taking a Fălciu seat in the Great National Assembly.[245] This allowed him to return to a secure position after Mihai Magheru took over as Ambassador, in late 1949.[246]

Resuming his scholarly work, Ralea had to refrain from calling himself a "sociologist", as that field of research had been declared "reactionary".[247] He was again given the position of psychology chair at the University of Bucharest, and was also made a member of the new Institute of History and Philosophy, whose president was Constantinescu-Iași. Ralea was seconded there by Constantin Ionescu Gulian, with whom he did research into the history of Romanian materialist philosophy.[248] He also prepared an anthropological tract, Explicarea omului ("Explaining Man"). Translated into the French by Eugène Ionesco,[249] it was published at Presses Universitaires de France.[250] In November 1948, he had been accepted into the recently purged Romanian Academy, at the same time as Balmuș, Raluca Ripan, Grigore Moisil, Ștefan Milcu, Camil Petrescu, and PCdR historian Mihail Roller.[251] A contributor to the PCdR daily, Scînteia, as well as to its youth supplement and its cultural reviews (Studii, Contemporanul, etc.),[1] Ralea also sat on the editorial staff of the Academy Historical Section's trimonthly, Buletin Științific, alongside Roller, David Prodan, and Constantin Moisil.[252]

Nevertheless, the Workers' Party (as the PCdR was known after absorbing the PSDR) was collecting evidence incriminating Ralea. During the 1947 clampdown on Freemasonry, Securitate officers included Ralea's name on a list of suspects.[253] In October 1949, taking its cue from Roller and Leonte Răutu, the party press carried notes critical of Ralea and Gulian's research.[254] The following year, Roller suggested that Ralea's introduction to the works of Vasile Conta was not up to Marxist standards, and also hinted that Ralea held too many offices.[255] The Securitate opened a file on him, which recorded his criticism of Roller and other "ignoramuses" promoted by the regime; in exchange, the Securitate labeled Ralea "opportunistic" and "a danger to our regime",[256] closely monitoring his contacts with Geamănu, Groza, Rosetti, Vianu, Victor Eftimiu and Mihail Ghelmegeanu.[46] From about 1950, his office at the institute was infiltrated by informants, and probably also bugged.[46][257]

Ralea responded to the pressures by presenting his services as an anti-American propagandist, making his first-hand experience in America into an irreplaceable asset; this assignment was inaugurated in January 1951, when Ralea and Gulian published in Studii a piece addressing the immorality of "American imperialists".[258] Working under direct Soviet supervision, Ralea took charge of a research project endorsed by the entire Institute: Caracterul antiștiințific și antiuman al psihologiei americane ("The Anti-Science and Anti-Humanity Nature of American Psychology", published 1954).[259] He was again able to rescue Vianu, this time from communist persecution,[260] and intervened to save the career of writer Costache Olăreanu.[261] More discreetly, he paid the bills of his former teacher, Rădulescu-Motru, who had been expelled from academia,[262] and rescued from eviction the conductor George Georgescu.[263] However, he could not protect either his brother-in-law Suchianu, who was arrested and held in communist prisons,[264] nor Chelariu, who was sacked and had to work as a rat-catcher.[178] Slama-Cazacu was also forced to abandon her doctoral studies, because of her political nonconformism.[265]

Ralea still had friendly contacts with his former supervisors in Foreign Affairs, though he complained to his peers that Pauker was snubbing him.[266] Pandrea, who had fallen out with the Workers' Party regime and spent time in prison, later alleged that Ralea, "the impenitent servant", cultivated the friendship of communist women, from Pauker to Liuba Chișinevschi (ro).[267] Ralea witnessed Pauker's 1952 downfall and banishment, and reputedly kept himself informed about her activities through mutual acquaintances.[268] His own survival in the post-Pauker era was an unusual feat. According to Pandrea, it was possible only because Ralea was "without scruples", always ready for a "cowardly submission", and a "valet" of Workers' Party potentates such as Ion Gheorghe Maurer.[85] As a sign that he was still protected by the regime, in February 1953 Ralea was awarded the Star of the People's Republic, Second Class.[269] A close bond still existed between him and Gheorghiu-Dej, who, upon winning the power struggle with Pauker, began cultivating his very own intellectual circle.[270]

The death of Joseph Stalin in early 1953 signaled a path toward less dogmatism. This initially hurt Ralea: Caracterul antiștiințific și antiuman, now seen as embarrassing, was not given mass circulation.[271] Nevertheless, Ralea supported Gheorghiu-Dej's adoption of a national communist platform, which was presented as an alternative to Soviet control.[272] Over the early 1950s, he had grown disgusted and alarmed by the impact of communist policies in education, but still fearful of approaching the topic in his dealings with communist potentates.[273] In 1955, with the relaxation of political pressures, he went public with his criticism, issued as a report to the Workers' Party leadership. It spoke about the poor scientific standards at Romania's universities, and criticized the appointment of political workers as school principals.[274] The report also condemned the Art Ministry for promoting "mediocrities" as cultural inspectors,[275] but avoided any proposal for actual liberalization.[276] By 1957, the Romanian school of psychology had been relaunched, and its official publications recommended Ralea as a main reference, but without mentioning Caracterul antiștiințific și antiuman.[277] Slama-Cazacu notes that Gheorghiu-Dej had him over as a guest in Eforie, where they discussed the handling of de-Stalinization.[278] At the time, some Romanian anticommunist circles also began taking an interest in Ralea, vainly hoping that he would be appointed premier of a post-Stalinist Romania.[178]

Final years

In 1956, the psychology section became an independent Institute, and Ralea became its chairman.[279] He was personally involved in securing ownership of its offices on Frumoasa Street, outside Calea Victoriei, previously held by the Comecom.[280] In August, he led a delegation to Moscow (whose other members included Oțetea, Tudor Arghezi, Marius Bunescu, George Oprescu, and Constantin Prisnea), where he signed for the partial return of the Romanian Treasure by its Soviet takers.[281] Also that year, Ralea published his historical essay on French politics and culture, Cele două Franțe ("The Two Frances"). It came out in a 1959 French edition, as Les Visages de France, with a preface by Roger Garaudy.[282] Ralea was also one of the select few Romanians, most of them trusted figures of the regime, who could reissue selections from their interwar literary contributions, at the specialized state company Editura de Stat pentru Literatură și Artă. Ralea was one of the first in this series, with the 1957 Scrieri din trecut ("Writings from the Past).[283]

Under a similar understanding with the regime, Ralea and other dignitaries could publish accounts of their travels in capitalist countries—in Ralea's case, the 1959 În extremul occident ("Into the Far West").[282] It had comments on the "iron fisted rule" of the United Fruit, and gibes at "the putrefied lazy specimens" of "exploiters" in pre-communist Cuba.[284] Slama-Cazacu suggests that her aging friend was simultaneously praised and humiliated by the regime: "forced to confine himself only to his activity at the faculty and the Academy", he was allowed to own a townhouse and cultivate his own vineyard, and was also provided with a "giant" Soviet ZIM as his service car.[26] He was also active in reintegrating culturally some intellectuals who had been imprisoned and rehabilitated: together with one such figure, Constantin I. Botez, he wrote the 1958 Istoria psihologiei ("History of Psychology").[285] According to memoirist C. D. Zeletin, Ralea and Vianu had a "courageous and noble" stand after the student protest of 1956: acting together, they obtained the release from Securitate custody of Dumitru D. Panaitescu, son of the critic Perpessicius.[286]

Ralea and his family lived at a luxurious villa on Washington Street, Dorobanți.[287] In 1961, he had been re-inducted into the literary canon, mentioned in official manuals as one of sixteen critics whose work supported "socialist construction".[288] Around that time, Ralea and Vianu mounted campaigns for Marxist humanism, and were elected to the National Board of UNESCO (Ralea was its vice president). Their actions were condemned at the time by the exile writer Virgil Ierunca, who described their "solemn agitation" as a new ruse on the part of Gheorghiu-Dej.[289] Ralea was then sent abroad with a mission to smooth out France–Romania relations in science and culture, meeting with his psychologist counterpart, Paul Fraisse.[278] He carried on him a dossier on exile writer Vintilă Horia, who had received the Prix Goncourt. It showed evidence of Horia's support for interwar fascism. Ralea's mission was hampered by revelations about his own compromises with fascism, published in Le Monde, Paris-Presse and the Romanian diaspora press, under such titles as: "Ralea used to lift his arm really high".[154] According to later assessments, the Horia affair and Ralea's participation therein were instrumented by the Securitate.[154][290]

Adhering to the official cultural policy, Ralea was making efforts to be admitted into the Workers' Party. His application was politely turned down,[291] but he was honored with the vice presidency of the Great National Assembly Presidium[154][292] and a seat on the republican Council of State.[293] At some point in the earliest 1960s, he was visited in Bucharest by Soviet psychologist Aleksei N. Leontiev, who confirmed Ralea and Slama-Cazacu's hopes that the Soviet Union would no longer deter research in the field.[278] In 1962, Ralea was one of the guest speakers at a Geneva conference on the generation gap, alongside Louis Armand, Claude Autant-Lara, and Jean Piaget.[294] Also that year, he helped with the recovery and reemployment of a former rival, Traian Herseni. Reportedly, Ralea excused Herseni's Iron Guard affiliation as a careerist move rather than a political crime.[295] According to Securitate sources, Herseni remained in charge of the Institute, since Ralea would only show up "for a couple of others".[46] Together, they published Sociologia succesului ("The Sociology of Success"); Herseni used the pseudonym Traian Hariton.[296] Despite such interventions, and his rescue of various other professionals,[46] Ralea was publicly shamed by the dissident poet Păstorel Teodoreanu, who nicknamed him the communist "Viceroy", or "Immo-Ralea".[297]

According to his younger colleague George C. Basiliade, Ralea was an "unfulfilled sybarite", whose luxurious lifestyle did not fit his physical frame and his background.[298] Notes in his Securitate file show that his case workers considered him half-senile and unable to concentrate on even the most basic political tasks.[46] Also heavy smoker, and prone to culinary excesses, Ralea checked himself in Otopeni hospital showing symptoms of facial nerve paralysis, with hypertension and fatigue.[299] Against the advice of his doctors, he decided to attend a UNESCO meeting in Copenhagen.[95][300] His acute fear of flying forced him to take the journey by train.[174]

Ralea died en route, on the morning of August 17, 1964; officially, this occurred outside East Berlin,[46][301] but, Slama-Cazacu notes, he was probably dead when the train was still crossing Czechoslovakia ("somewhere near Prague").[196] The autopsy, performed in East Germany, revealed that he had survived tuberculosis (partly confirming his decades-long hypochondriasis), and also that his neurological decline was schwere Gehimsklerose ("severe cerebral sclerosis").[196] Ralea's body was transported back to Bucharest, and a day of mourning was observed nationally. After being laid in state at the Great National Assembly,[46] he was given a burial at Bellu Cemetery. This reflected one of his wishes, that of being close in death to the national poet, Mihai Eminescu.[95] Ralea's final contribution in the press was a UNESCO-themed interview with Cristian Popișteanu, published by Lumea that same month.[302] He and Herseni had been working on a textbook, Introducere în psihologia socială ("Companion to Social Psychology"), which only saw print in 1966.[303]

Sociology of culture

Generic traits

As seen by Zavarache, Ralea was a man of "outstanding intelligence" with an "encyclopedic knowledge, tightly aligned with the rhythms of Western culture."[304] Ralea's contemporaries left remarks on not just his hyperactivity, but also his neglect of details, and his eclecticism. Slama-Cazacu recalls his habit of reading articles, including scientific ones, "at a glance", and once appointing the staff of a psychology journal "with his nonchalant and hurried manner, calling out the names of people as he happened to see them in the room";[305] Pompiliu Constantinescu also remarked of "petulant" Ralea: "Here is a soul who will not stand for the label of specialization!"[306] In 1926, Eugen Lovinescu dismissed Ralea as "a fecund ideologue, paradoxical in his association and dissociation of varied and superficial ideals that have happened to have points of contact with Romanian literature."[307] He reads both Ralea and Suchianu as displays of "useless erudition" and "failure of logic".[308] Completing this verdict, Monica Lovinescu saw Ralea as "not truly a literary critic", but "a sociologist, a psychologist, a moralist—a moralist with no morals, and yet a moralist".[309] More leniently, George Călinescu noted that Ralea was an "epicurean" of "vivid intelligence", who only chronicled "books that he has enjoyed reading". His free associations of concepts were "very often surprising, quite often admirable".[59] Ralea, Călinescu proposes, was Romania's own "little Fontenelle".[2]

After his French sojourn, Ralea infused Poporanism and collectivism with both Durkheim's corporatism[310] and Marx's theory of "class consciousness".[311] In his earliest work, he also referenced Ludwig Gumplowicz's ideas about the fundamental inequality of class-based societies. These references helped him build a critique of innate "class solidarity" as presumed by early corporatism, and also of Proudhon's mutualist economics.[312] Despite this collectivist-functionalist outlook, and although he spoke out against art for art's sake, Ralea was adamant that strictly sociological explanations of creativity were doomed to fail. As he put it, all attributes of a writer were "subsidiary to [his] creative originality".[313] Additionally, Ralea reduced aestheticism and social determinism to the basic units of "aesthetics" and "ethnicity". As he saw it, an ethnic consciousness was biologically and psychologically necessary: it helped structure perception, giving humans a reference point between the particularity and generality.[314]

In a 1972 piece, communist intellectual Paul Georgescu acknowledged Ralea's comparative superficiality, noting that he knew less literary history that Călinescu, less aesthetics than Vianu, less philosophy than Mircea Florian, and less sociology that Henri H. Stahl; but also that his improvisation in such fields came with "fertile results", particularly since it applied itself to a "living reality". Georgescu opined that "those who have always questioned Ralea for his radical, bourgeois-democratic, persistently leftist, substantially antifascist militancy [have claimed that] an intellectual never engages in politics. This is a syncopated pretext of the hypocritical, cowardly aestheticists."[315] Ralea's editor Nicolae Tertulian (himself a Marxist philosopher) asserts that the "anti-speculative and anti-metaphysical" nature of Durkheimian sociology was a "fecund" influence on Ralea's own theoretical outlook. This blended into politics: "Ralea would staunchly underscore that the guarantee of individual freedoms, far from equating a worship of the self [...], implies a strong tendency toward social solidarism, toward the organization and cooperation of all democratic forces against Caesarian, oligarchic tendencies."[316] This political pedagogy was also once highlighted by Ralea's enemy-turned-ally, Petre Pandrea (ro): "[L'idée de la révolution... is written] with a sincerity that defies chauvinistic hypocrisy and does not shy away from tearing the masks off of so many things viewed as sublime or holy by the innocent folk, or treated as such by Tartuffe-esque scoundrels."[317]

National psychology

An artist, Ralea argued in 1925, was "obliged" to address the national society he lived in, "at the present stage in civilization": "If he were human, he would be discarding specificity itself, that is to say the very essence of art, and would fall into science; if he were too specific, too original, he'd stand to lose his means of expression, the point of contact with his public".[318] Ralea believed that the origin of beauty was biological, before being human or social; he also claimed (questionably so, according to art critic Petru Comarnescu) that traditional society allowed no depiction of ugliness before the arrival of Christian art.[319] With this analysis of aesthetic principles, borrowing from Henri Bergson, Ralea toned down his own rationalism and determinism, taking in relativism and intuitionism.[320] With his respect for critical intuition, his critique of determinism, and his cosmopolitanism, he came unexpectedly close to the aestheticism of his rival Lovinescu, and, though him, to the "aesthetic autonomism" of Titu Maiorescu.[321] Ralea even sketched out his own relativist theory, according to which works of art could have limitless interpretations (or "unforeseen significances"),[322] thus unwittingly paralleling, or anticipating, the semiotics of Roland Barthes.[323] With Între două lumi, he still rejected individualism and subjectivity, but also nuanced his corporatist collectivism. As he noted, militancy in favor of either philosophy had sparked the modern crisis. The solution, Ralea suggested, was for man to rediscover the simple joys of anonymity.[194]

In his essay Fenomenul Românesc ("The Romanian Phenomenon"), Ralea elaborated on the issue of Romanian national psychology. He understood this as a natural development of Dimitrie Gusti's sociological "science of the nation", but better suited to the topic and more resourceful.[324] His core statement was summarized in 1937 by a sympathetic reviewer, Ion Biberi, as: "one cannot reach the universal unless it is by expressing one's national reality"; this prompted the nationalists at Neamul Românesc to note that Ralea had validated their own thesis, and would therefore qualify as a "retrograde" by left-wing standards.[325] Expanding on his musings about Romania's atheistic traditions, Ralea explored specificity on his own terms. He noted that Romanians were structurally opposed to mysticism, which could not compliment their true character: "good-natured, even-minded, sharp-witted like all meridional men, [and] extremely lucid."[326] The "Romanian soul" was therefore an adaptable and pragmatic entity, mixing a Western propensity for action with a Levantine fatalism.[327] Combating antisemitism, Ralea applied this theory to the issue of European Jewish intelligence: quoting Werner Sombart, he deduced that the "rationalist", "progressive" and "utilitarian" essence of Jewishness was socially determined by the Jews' participation in capitalist competition.[328]

Although Ralea was personally responsible for establishing a laboratory of experimental psychology at Iași, he in fact abhorred experimental methods, and preferred to rely on intuition.[329] As a theorist, he gave a humanistic praise to dilettantism and vitality, in the face of philosophical sobriety. He commended Ion Luca Caragiale, the creator of modern Romanian humor, as the voice of lucidity, equating irony with intelligence.[330] He extended this vision in analyzing humorous poems by his friend George Topîrceanu, arguing (alongside Alexandru A. Philippide) that good comedy required both a philosophical and a lyrical attitude.[331] As noted by Călinescu, Ralea "either intentionally or unconsciously [suggests] that intense flippancy is in fact sobriety".[2] Ralea did have his uncertainties about the grounding of his own idea. Caragiale's humor risked making Romanians too accepting of their superficiality: "maybe this genius portraitist of our bourgeoisie has done us a great harm".[332] During his polemic with Sburătorul modernism, Ralea attacked the new schools of aesthetics for their artificiality and obsessiveness: "Not one of the truly terrible chapters in life is familiar to [the modernists]. They are not humans, just clowns. [...] Only the demented and children are unilateral. True aesthetics expresses the mature and normal spiritual functions. The alternative is comparative or infantile aesthetics".[333] According to Monica Lovinescu, his critique of "lassitude" and "cowardice" in urban life is "a severe diagnostic of his own disease."[334]