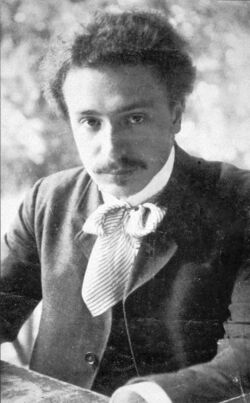

Biography:Vasily Seseman

Vasily Seseman (several other latinizations of his name exist, Lithuanian: Vosylius Sezemanas, Russian: Василий Эмильевич Сеземан) (June 11, 1884, Vyborg — March 23, 1963, Vilnius) was a Russia n and Lithuanian philosopher, a representative of Marburg school of neo-Kantianism. He is mostly remembered for his role in fostering philosophy in newly independent Lithuania and developing Lithuanian philosophical vocabulary (most remarkable are his translations of Aristotle into Lithuanian and contributions to Lithuanian encyclopedias). A close associate of Viktor Zhirmunsky and Lev Karsavin (ru), as a prisoner of Gulag he was also an informal philosophy tutor and supporter of Buddhist writer Bidia Dandaron.

Biography

Born to the family of a medical doctor of Finnish Swedish descent and a Baltic German mother, he was initially named Wilhelm Sesemann and attended the Lutheran school (Katharinenschule) in St Petersburg. As he grew up, he adopted a more Russian identity, changing Wilhelm to Wassilij (Vasily) and embracing Russian Orthodox Christianity.

After two years of medical studies he turned to philosophy, fervently studying classical authors under Nikolay Lossky and classical languages under Tadeusz Stefan Zieliński at University of St. Petersburg. In 1909-1911 the university sent him to Germany to prepare him for a teaching career. In Berlin and Marburg, he took courses in philosophy, psychology, and pedagogics under Hermann Cohen, Paul Natorp, Ernst Cassirer, Hermann Alexander Diels, and Heinrich Wölfflin. In Germany he also met José Ortega y Gasset who made a great impression on him, and re-established a lifelong friendship with Nicolai Hartmann who in St Petersburg had influenced Vasily's decision to switch from medicine to philosophy.

Upon his return to St. Petersburg, Seseman taught philosophy and classical languages until World War I, when he enlisted as a volunteer in the Russian army.

From 1915 to 1917 he taught philosophy as a privatdozent at the University of St. Petersburg, and from 1918 to 1919 at the Viatka Pedagogical Institute. He received a docentship in Saratov, where he worked (together with Viktor Zhirmunsky) until 1921.

Later Seseman, as a Finnish citizen, emigrated to Finland and then to Berlin, where he finally found a teaching position at the Russian Institute.

In 1923 Seseman was invited to become a professor at Kaunas University in Lithuania. When Vilnius was regained by Lithuania, he moved there and worked at the University of Vilnius until the Nazis closed it down in 1943. He worked as a German language teacher during the German occupation, and led a philosophy course in the Jewish ghetto.

According to his stepdaughter's interview, while living in poverty, at his place in central Vilnius he also hid from the Nazis a Jewish girl (who later disappeared), and supplied ghetto Jews with false documents allowing emigration. He made a narrow escape from being burnt alive for being a supporter of the Jews while the Nazi troops were abandoning the city for the Soviet troops. His efforts on behalf of the Jews were posthumously recognized by the Lithuanian government awarding him a medal.

He spent 1945-1950 teaching at the University of Vilnius again, but then was arrested by the Soviet authorities, accused of “anti-Soviet activities” and “relations with Zionist organizations” and sentenced to 15 years of labor camps. In Siberia he met a Buddhist tantra practitioner Bidia Dandaron who learned a lot from Seseman, as a result embracing Kantian ideas and developing his own synthesis of Tibetan Buddhist and European philosophical thought in his writings. Their friendship continued after they were released.

In 1956 Seseman was released, in 1958 rehabilitated and resumed his professorship at Vilnius where he taught for the rest of his life.

Philosophy

Seseman liked to call his philosophy “gnoseological idealism”, trying to revive metaphysics through a re-evaluation of the metaphysical tradition of ontology. His other philosophical aim was to overcome the dichotomies between the subjective-psychological and the objective-realistic in the theory of knowledge and metaphysics in general.

He deliberated on the dangers of materialism and positivism for European thought.

Seseman’s concern for formal questions in linguistics and aesthetics may make him a precursor of modern semiotics.

Bibliography

Writings

- “Logik und Ontologie der Möglichkeit: August Faust. Der Möglichkeitsgedanke. 1. Teil: Antike Philosophie. 2. Teil: Chistliche Philosophie” in Blätter für deutsche Philosophie Bd. 10, Heft 2 (Heidelberg: 1932): 161-171.

- “Die bolschewistische Philosophie in Sowiet Russland” in Der russische Gedanke Heft 2 (Bonn: 1931): 176-183.

- “Die logischen Gesetze und das Sein: a) Die logischen Gesetze im Verhältnis zum subjektbezogenen und psychischen Sein. b) Die logischen Gesetze und das daseinsautonome Sein” in Eranus Vol 2 (Kaunas: 1931): 60-230.

- “Zum Problem der logischen Paradoxien” in Eranus vol. 3 (Kaunas: 1935): 5-85.

- “Zum Problem der Dialektik” in Blätter für deutsche Philosophie Bd. 9, Heft 1 (Berlin: 1935): 28-61.

- Logika (Kaunas: Lietuvos universitetuo Humanitariniu mokslu fakultete, 1929), 304 p.

- Paskaitos (Lectures) (Kaunas: Humanitariniu mokslu fakultetas, 1929)

- Estetika (Vilnius: Mintis, 1970), 463 p.

- Sesemann, Vasily, Aesthetics, Translated by Mykolas Drunga, Edited and introduced by Leonidas Donskis (Amsterdam - New York, NY: Rodopi,2007),279 p.

- Sesemann, Vasily, Selected Papers, Translated by Mykolas Drunga, Edited by Mykolas Drunga and Leonidas Donskis, Introduced by Arūnas Sverdiolas (Amsterdam - New York, NY: Rodopi,2010),88 p.

The Lithuanian edition of Seseman’s works consists of two volumes:

- Vol. 1: Gnoseologia (Vilnius: Mintis, 1987)

- Vol. 2: Filosofijos istorija (Vilnius: Mintis, 1997)

Translations

- Lossky’s Logica (Petrograd: Nauka i shkola, 2 vol. 1922) as Handbuch der Logik (Leipzig: Teubner, 1927), 445 pages.

- Aristotle’s De Anima as: Aristotelis: Apie siela (Vilnius: Valstybini politiais ir mokslinis literatûros leidykla, 1959) with a 60 pages long introduction into the philosophy of Aristotle.

Literature

- Botz-Bornstein, Thorsten: Vasily Sesemann: experience, formalism, and the question of being. (Vosylius Sezemanas). On the boundary of two worlds (Vol 7). Rodopi, 2006. ISBN:90-420-2092-X

- Anilionyte, Loreta & Lozuraitis, Albinas: The Life of Vosylius Sezemanas and His Critical Realism.

This article uses only URLs for external sources. (2021) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

|