Biology:Bathypterois

| Bathypterois | |

|---|---|

| |

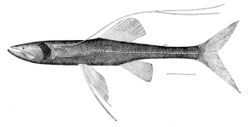

| Mediterranean spiderfish (B. dubius) | |

| |

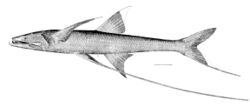

| Tripodfish (B. grallator) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Aulopiformes |

| Family: | Ipnopidae |

| Genus: | Bathypterois Günther, 1878 |

Bathypterois is a genus of deepsea tripod fishes. They are a diverse genus that belong to the greater family Ipnopidae and order Aulopiformes. They are distinguished by having two elongated pelvic fins and an elongated caudal fin, which allow them to move and stand on the ocean floor, much like a tripod, hence the common name.[2] Bathypterois are distributed worldwide with some particular species of the genus having specialized environmental niches, such as lower dissolved oxygen concentrations.[3] Bathypterois have a reduced eye size, highly specified extended fins, and a mouth adapted to filter feeding.[2] They are filter feeders whose main food source is benthopelagic planktonic calanoid copepods, but some variation is seen with maturity in secondary food sources.[4] Bathypterois use their three elongated fins for a wide range of motion from landing to standing on the ocean floor to catching prey, for which these fins serve as specialized perceptory organs.[2] Bathypterois have both male and female gonads at once making, them simultaneous hermaphrodites, whose gonads go through five stages of development following seasonal autumn spawning.[5]

Species

There are 19 different species within Bathypterois that are spread around the world.[6] Six of these belong to the subgenus Bathycygnus.[7] The taxa Bathypterois was first named and identified in 1878 by German zoologist Albert Günther. The newest addition, Bathypterois andriashevi, was named and identified in 1988 by Kenneth Sulak and Yuri Shcherbachev.[7] Species are most effectively distinguished by characteristics such as dorsal, caudal and pectoral fin patterns, scale patterns, and where they most often occur both ecologically and geographically.[7][3]

The 19 recognized species in this genus are:[8]

- Bathypterois andriashevi Sulak & Shcherbachev, 1988

- Bathypterois atricolor Alcock, 1896 (Attenuated spider fish)

- Bathypterois bigelowi Mead, 1958

- Bathypterois dubius Vaillant, 1888 (Mediterranean spiderfish)

- Bathypterois filiferus Gilchrist, 1906

- Bathypterois grallator (Goode & T. H. Bean, 1886) (Tripod fish)

- Bathypterois guentheri Alcock, 1889 (Tribute spiderfish)

- Bathypterois insularum Alcock, 1892

- Bathypterois longicauda Günther, 1878

- Bathypterois longifilis Günther, 1878 (Feeler fish)

- Bathypterois longipes Günther, 1878 (Abyssal spiderfish)

- Bathypterois oddi Sulak, 1977

- Bathypterois parini Shcherbachev & Sulak, 1988

- Bathypterois pectinatus Mead, 1959

- Bathypterois perceptor Sulak, 1977

- Bathypterois phenax A. E. Parr, 1928 (Blackfin spiderfish)

- Bathypterois quadrifilis Günther, 1878

- Bathypterois ventralis Garman, 1899 (Ventrad spiderfish)

- Bathypterois viridensis (Roule, 1916)

Distribution and habitat

The niches the different species within Bathypterois live in vary and can be as deep as 6,000 m in and in both temperate or tropical oceans.[6] Some species, such as Bathypterois ventralis, are known to prefer warmer waters and lower dissolved oxygen concentrations/oxygen deficient zones, which they are well adapted for.[3] Certain species, such as Bathypterois filiferus are endemic to the southern Pacific and northern Indian oceans, while others such as Bathypterois longipes, are endemic to the mid/southern Atlantic.[7] Some species prefer the continental slope while others prefer the depth of the abyssopelagic.[7] However, in general, Bathypterois has a very broad distribution with much overlap between environments since they are so well adapted to survival in a variety of niches.[3]

Morphology

Bathypterois are typically around 30 cm in size but have been observed as large as 43.4 cm in size.[8] Their eyes tend to be small in size.[2] The coloring of the genus varies from colorless to black as well as uniform to multicolored among the different species within the genus.[7] Bathypterois tend to have non-sensory pads at the end of extended pelvic and caudal fin ray elements.[2] These extended elements can extend to up to three times that of the body, or around 1 meter.[10] The pads allow the rays to rest on the sea floor creating the sedentary three point (tripod) stance that is typically observed of Bathypterois.[2] The pectoral fins are also extended, and are sensitive to sensory input as a result of the spinal nerves having three innervations and being enlarged in the pectoral fins of most Bathypterois species.[2] They have two gonads, one male and one female. The male testicular gonad is more dorsal than the female ovarian gonad.[11] Both gonads work, meaning they are able to produce sperm or eggs respectively, and are clearly unique from the other.[5] Their mouth is large and upturned and contains little dentition.[2] The laminar gill rakers are long, thin, and covered in small spines.[2][4] They tend to have stomachs that are linear and poorly differentiated.[4]

Swimming and motion

Bathypterois have two main pelvic fins and caudal fin that serve a variety of purposes, from perching and walking on the seafloor, to swimming and landing, to sensing and capturing prey.[2] When perching/landing the pelvic fins, they act as "stilts", while the third caudal fin then closes the tripod and allows for stability.[2] Bathypterois are predominantly observed with their body positioned upstream, facing the current in order to wait for prey and conserve energy.[12] Their swimming is described as intervallic and "subcarangiform", meaning fins and body are used in addition to the tail.[2] These fins also play a very important role in hunting technique--they are used, in essence, as hands. Due to both poor eyesight and a lack of light at abyssal depths, Bathypterois use their pelvic fins to orient themselves as well as to sense and seize prey around them.[13][2]

Feeding and diet

What they feed on changes based on maturity, however they are always filter feeders. In order to feed, they have laminar gill rakers that are long and thin that allow them to capture planktonic prey.[4] They face into the current in the tripod stance allowing the food to come to them.[10] The main food source for them is benthopelagic planktonic calanoid copepods, no matter the depth and maturity. However, between 1800 meters and 2250 meters the secondary prey is different for juvenile and mature Bathypterois.[4] Both mature and juvenile organisms diet increases to include endobenthic and epibenthic prey as the secondary food source, which for juveniles is benthic tanaidaceans and for mature Bathypterois is mysids.[4][13] The difference in diet between juvenile and mature organisms is not big but does vary across the different species.[13] It has been indicated that the species Bathypterois grallator eats larger, gelatinous prey as well as the other common food sources for species within the genus.[2]

Reproduction

Bathypterois is a genus of simultaneously hermaphroditic species. They will only give birth/reproduce once a year as a result of monocyclic ovaries.[11] There are five stages to the development and maturation of the gonads, which are immature, developing, maturing, mature, and post-spawning. These developmental stages include both macroscopic and microscopic changes, as well as growth until the gonads are flaccid in the last stage. The gonads go from two colorless filaments (immature), to being a pinkish white (developing), to pink with eggs visible under a stereomicroscope (maturing), to orange with eggs visible to the eye (mature), and finally to reddish with little visible eggs (post-spawning).[5] Spawning is thought to occur in late September through early November and the next egg won't develop until after a short rest period.[11] The maturity is thought to peak around April but can be seen from March to November for both male and female gonads. Indicating seasonal autumn spawning within Bathypterois.[5] They are able to mate with other fish of their species, or they can fertilize themselves, since they have the two different gonads. Self fertilization occurs and the fish excretes both sperm and egg into the water, but when mating with another fish they each only excrete one.[10]

References

- ↑ "BOLD:AAF0023 | BOLDSYSTEMS". http://www.boldsystems.org/index.php/Public_BarcodeCluster?clusterguid=BOLD:AAF0023.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 Davis, Matthew P.; Chakrabarty, Prosanta (April 2011). "Tripodfish (Aulopiformes: Bathypterois ) locomotion and landing behaviour from video observation at bathypelagic depths in the Campos Basin of Brazil". Marine Biology Research 7 (3): 297–303. doi:10.1080/17451000.2010.515231. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/biosci_pubs/808.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Cruz-Acevedo, Edgar; Betancourt-Lozano, Miguel; Aguirre-Villaseñor, Hugo (23 September 2016). "Distribution of the deep-sea genus Bathypterois (Pisces: Ipnopidae) in the Eastern Central Pacific". Revista de Biología Tropical 65 (1): 89–101. doi:10.15517/rbt.v65i1.23726. PMID 29466631.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Carrasson, Maite; Matallanas, Jesus (1 April 2001). "Feeding ecology of the Mediterranean spiderfish, Bathypterois mediterraneus (Pisces: Chlorophthalmidae), on the western Mediterranean slope". Fishery Bulletin 99 (2): 266–274. Gale A75434042. https://spo.nmfs.noaa.gov/content/feeding-ecology-mediterranean-spiderfish-bathypterois-mediterraneus-pisces-chlorophthalmidae.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Porcu, Cristina; Follesa, Maria Cristina; Grazioli, Eleonora; Deiana, Anna Maria; Cau, Angelo (June 2010). "Reproductive biology of a bathyal hermaphrodite fish, Bathypterois mediterraneus (Osteichthyes: Ipnopidae) from the south-eastern Sardinian Sea (central-western Mediterranean)". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 90 (4): 719–728. doi:10.1017/S0025315409991330.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Angulo, Arturo; Bussing, William A.; López, Myrna I. (June 2015). "Occurrence of the tripodfish Bathypterois ventralis (Aulopiformes: Ipnopidae) in the Pacific coast of Costa Rica". Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 86 (2): 546–549. doi:10.1016/j.rmb.2015.04.025.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Sulak, Kenneth J.; Shcherbachev, Yuri N. (1988). "A New Species of Tripodfish, Bathypterois (Bathycygnus) andriashevi (Chlorophthalmidae), from the Western South Pacific Ocean". Copeia 1988 (3): 653–659. doi:10.2307/1445383.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). Species of Bathypterois in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- ↑ By NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, INDEX-SATAL 2010, NOAA/OER - http://www.photolib.noaa.gov/htmls/expl2148.htm, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16328994

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "Aquarium of the Pacific | Online Learning Center | Tripod Fish". https://www.aquariumofpacific.org/onlinelearningcenter/species/tripod_fish#:~:text=of%20the%20species.-,When%20self-fertilization%20occurs,%20the%20tripod%20fish%20spawns%20both%20sperm,eggs%20into%20the%20water%20column.&text=SPECIAL%20NOTES-,The%20tripod%20fish.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Fishelson, Lev; Galil, Bella S. (2001). "Gonad Structure and Reproductive Cycle in the Deep-Sea Hermaphrodite Tripodfish, Bathypterois mediterraneus (Chlorophthalmidae, Teleostei)". Copeia 2001 (2): 556–560. doi:10.1643/0045-8511(2001)001[0556:GSARCI2.0.CO;2].

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 By Bahamas Deep-Sea Coral Expedition Science Party, NOAA-OER. - http://www.photolib.noaa.gov/htmls/expl1868.htm, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16328440

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Carrassón, Maite; Matallanas, Jesús (30 December 2002). "Feeding habits of Cataetyx alleni (Pisces: Bythitidae) in the deep western Mediterranean". Scientia Marina 66 (4): 417–421. doi:10.3989/scimar.2002.66n4417.

Wikidata ☰ Q2708720 entry

|