Biology:Bleb (cell biology)

This article is missing information about prokaryotic blebs under the heading "membrane vesicles" -- actin's generally not involved and there are three classes by taxonomy. See bacterial outer membrane vesicles, PMID 23123555 and PMID 31942073. (September 2022) |

In cell biology, a bleb is a bulge of the plasma membrane of a cell, characterized by a spherical, "blister-like", bulky morphology.[2][3][4] It is characterized by the decoupling of the cytoskeleton from the plasma membrane, degrading the internal structure of the cell, allowing the flexibility required for the cell to separate into individual bulges or pockets of the intercellular matrix.[4] Most commonly, blebs are seen in apoptosis (programmed cell death) but are also seen in other non-apoptotic functions. Blebbing, or zeiosis, is the formation of blebs.

Formation

Initiation and expansion

Bleb growth is driven by intracellular pressure (abnormal growth) generated in the cytoplasm when the actin cortex undergoes actomyosin contractions.[5] The disruption of the membrane-actin cortex interactions[4] are dependent on the activity of myosin-ATPase[6] Bleb initiation is affected by three main factors: high intracellular pressure, decreased amounts of cortex-membrane linker proteins, and deterioration of the actin cortex.[7][8] The integrity of the connection between the actin cortex and the membrane are dependent on how intact the cortex is and how many proteins link the two structures.[7][8] When this integrity is compromised, the addition of pressure is able to make the membrane bulge out from the rest of the cell.[7][8] The presence of only one or two of these factors is often not enough to drive bleb formation.[8] Bleb formation has also been associated with increases in myosin contractility and local myosin activity increases.[7][8]

Bleb formation can be initiated in two ways: 1) through local rupture of the cortex or 2) through local detachment of the cortex from the plasma membrane.[9] This generates a weak spot through which the cytoplasm flows, leading to the expansion of the bulge of membrane by increasing the surface area through tearing of the membrane from the cortex, during which time, actin levels decrease.[5] The cytoplasmic flow is driven by hydrostatic pressure inside the cell.[10][3] Before the bleb is able to expand, pressure must build enough to reach a threshold.[8] This threshold is the amount of pressure needed to overcome the resistance of the plasma membrane to deformation.[8]

Artificial induction

Bleb formation has been artificially induced in multiple lab cell models using different methods.[11] By inserting a micropipette into a cell, the cell can be aspirated rapidly until destruction of cortex-membrane bonds causes blebbing.[11] Breakage of cortex-membrane bonds has also been caused by laser ablation and injection of an actin depolymerizing drug, which in both cases eventually led to blebbing of the cell membrane.[11] Artificially increased levels of myosin contractility were also shown to induce blebbing in cells.[11] Some viruses, such as the poxvirus Vaccinia, have been shown to induce blebbing in cells as they bind to surface proteins.[12] Although the exact mechanism is not yet fully understood, this process is crucial to endocytosing the virion and subsequent infection.[12]

Cellular function

Apoptotic function

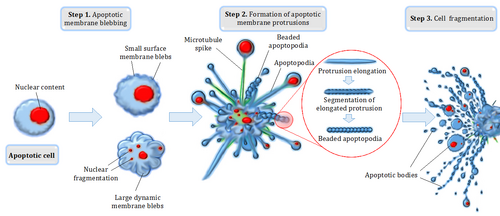

Blebbing is one of the defined features of apoptosis.[6] During apoptosis (programmed cell death), the cell's cytoskeleton breaks up and causes the membrane to bulge outward.[13] These bulges may separate from the cell, taking a portion of cytoplasm with them, to become known as apoptotic blebs.[14] Phagocytic cells eventually consume these fragments and the components are recycled.

Two types of blebs are recognized in apoptosis. Initially, small surface blebs are formed. During later stages, larger so-called dynamic blebs may appear, which may carry larger organelle fragments such as larger parts of the fragmented apoptotic cell nucleus.[15]

Function in cell migration

Along with lamellipodia, blebs serve an important role in cell migration.[7][11] Migrating cells are able to polarize the formation of blebs so blebbing only occurs on the leading edge of the cell.[7][11] A 2D moving cell is able to use adhesive molecules to gain traction in its environment while blebs form at the leading edge.[7][11] By forming a bleb, the center of mass of the cell shifts forward and an overall movement of cytoplasm is accomplished.[7] Cells have also been known to accomplish 3D bleb-based movement through a process called chimneying.[7][11] In this process, cells exert pressure on the top and bottom substrates by squeezing themselves, causing a bleb on the leading edge to grow and the cell to have a net movement forward.[7][11]

Miscellaneous functions

Blebbing also has important functions in other cellular processes, including cell locomotion, cell division, and physical or chemical stresses. Blebs have been seen in cultured cells in certain stages of the cell cycle. These blebs are used for cell locomotion in embryogenesis.[16] The types of blebs vary greatly, including variations in bleb growth rates, size, contents, and actin content. It also plays an important role in all five varieties of necrosis, a generally detrimental process. However, cell organelles do not spread into necrotic blebs.

Inhibition

In 2004, a chemical known as blebbistatin was shown to inhibit the formation of blebs.[18] This agent was discovered in a screen for small molecule inhibitors of nonmuscle myosin IIA.[18]Blebbistatin allosterically inhibits myosin II by binding near the actin-binding site and ATP-binding site.[19] This interaction stabilizes a form of myosin II that is not bound to actin, thus lowering the affinity of myosin with actin.[18][19][20][21] By interfering with myosin function, blebbistatin alters the contractile forces that impinge on the cytoskeleton-membrane interface and prevents the build up of intracellular pressure needed for blebbing.[8][18][19][20][21] Blebbistatin has been investigated for its potential medical uses to treat fibrosis, cancer, and nerve injury.[19] However, blebbistatin is known to be cytotoxic, photosensitive, and fluorescent, leading to the development of new derivatives to solve these problems.[19] Some notable derivatives include azidoblebbistatin, para-nitroblebbistatin, and para-aminoblebbistatin.[19]

References

- ↑ "Cell disassembly during apoptosis" (in en). WikiJournal of Medicine 4 (1). 2017. doi:10.15347/wjm/2017.008.

- ↑ "Bleb Formation in Human Fibrosarcoma HT1080 Cancer Cell Line Is Positively Regulated by the Lipid Signalling Phospholipase D2 (PLD2)" (in en). Achievements in the Life Sciences 10 (2): 125–135. 2016-12-01. doi:10.1016/j.als.2016.11.001. ISSN 2078-1520.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Role of cortical tension in bleb growth". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106 (44): 18581–18586. November 2009. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903353106. PMID 19846787. Bibcode: 2009PNAS..10618581T.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Cell motility through plasma membrane blebbing". The Journal of Cell Biology 181 (6): 879–884. June 2008. doi:10.1083/jcb.200802081. PMID 18541702.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "A short history of blebbing". Journal of Microscopy 231 (3): 466–478. September 2008. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2818.2008.02059.x. PMID 18755002.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Blebs produced by actin-myosin contraction during apoptosis release damage-associated molecular pattern proteins before secondary necrosis occurs". Cell Death and Differentiation 20 (10): 1293–1305. October 2013. doi:10.1038/cdd.2013.69. PMID 23787996.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 "Blebs lead the way: how to migrate without lamellipodia". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 9 (9): 730–736. September 2008. doi:10.1038/nrm2453. PMID 18628785.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 "The role and regulation of blebs in cell migration". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. Cell adhesion and migration 25 (5): 582–590. October 2013. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2013.05.005. PMID 23786923.

- ↑ "Blebs lead the way: how to migrate without lamellipodia". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 9 (9): 730–736. September 2008. doi:10.1038/nrm2453. PMID 18628785.

- ↑ "Non-equilibration of hydrostatic pressure in blebbing cells". Nature 435 (7040): 365–369. May 2005. doi:10.1038/nature03550. PMID 15902261. Bibcode: 2005Natur.435..365C.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 "The role and regulation of blebs in cell migration". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. Cell adhesion and migration 25 (5): 582–590. October 2013. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2013.05.005. PMID 23786923.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Vaccinia virus uses macropinocytosis and apoptotic mimicry to enter host cells". Science 320 (5875): 531–535. April 2008. doi:10.1126/science.1155164. PMID 18436786. Bibcode: 2008Sci...320..531M.

- ↑ "Apoptosis: mechanisms and relevance in cancer". Annals of Hematology 84 (10): 627–639. October 2005. doi:10.1007/s00277-005-1065-x. PMID 16041532.

- ↑ "Recent developments in the nomenclature, presence, isolation, detection and clinical impact of extracellular vesicles". Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis 14 (1): 48–56. January 2016. doi:10.1111/jth.13190. PMID 26564379.

- ↑ "Defining the morphologic features and products of cell disassembly during apoptosis". Apoptosis 22 (3): 475–477. March 2017. doi:10.1007/s10495-017-1345-7. PMID 28102458.

- ↑ "Apoptotic and necrotic blebs in epithelial cells display similar neck diameters but different kinase dependency". Cell Death and Differentiation 10 (6): 687–697. June 2003. doi:10.1038/sj.cdd.4401236. PMID 12761577.

- ↑ Optopharma (2017-07-03), English: 2D structure of blebbistatin, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blebbistatin.png, retrieved 2021-11-23

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 "Specificity of blebbistatin, an inhibitor of myosin II". Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility 25 (4-5): 337–341. 2004. doi:10.1007/s10974-004-6060-7. PMID 15548862.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 "Targeting Myosin by Blebbistatin Derivatives: Optimization and Pharmacological Potential". Trends in Biochemical Sciences 43 (9): 700–713. September 2018. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2018.06.006. PMID 30057142.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Dissecting temporal and spatial control of cytokinesis with a myosin II Inhibitor". Science 299 (5613): 1743–1747. March 2003. doi:10.1126/science.1081412. PMID 12637748. Bibcode: 2003Sci...299.1743S.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Mechanism of blebbistatin inhibition of myosin II". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 279 (34): 35557–35563. August 2004. doi:10.1074/jbc.M405319200. PMID 15205456.

Further reading

- "Life and times of a cellular bleb". Biophysical Journal 94 (5): 1836–1853. March 2008. doi:10.1529/biophysj.107.113605. PMID 17921219. Bibcode: 2008BpJ....94.1836C.

- "Reassembly of contractile actin cortex in cell blebs". The Journal of Cell Biology 175 (3): 477–490. November 2006. doi:10.1083/jcb.200602085. PMID 17088428.

- "Membrane tether formation from blebbing cells". Biophysical Journal 77 (6): 3363–3370. December 1999. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77168-7. PMID 10585959. Bibcode: 1999BpJ....77.3363D.

- Drug Stops Motor Protein, Shines Light on Cell Division - FOCUS March 21, 2003. Retrieved April 8, 2008.

- "Regulation of plasma membrane blebbing by the cytoskeleton". Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 73 (4): 488–499. June 1999. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(19990615)73:4<488::AID-JCB7>3.0.CO;2-P. PMID 10733343.

External links

|