Biology:Border beaked gecko

| Border beaked gecko | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Family: | Diplodactylidae |

| Genus: | Rhynchoedura |

| Species: | R. angusta

|

| Binomial name | |

| Rhynchoedura angusta Pepper, Doughty, Hutchinson, & Keogh, 2011

| |

The border beaked gecko (Rhynchoedura angusta) is a gecko endemic to Australia in the family Gekkonidae.[1] It is known for its distinctive beak-like snout and ability to camouflage itself in its surroundings.

Description

The border beak gecko is small with a long, slender body and short, pointed, beak-like snout.[2] It grows to up to 95 millimeters in length.[3] It has large protuberant eyes that provide almost all-around vision[4] with reddish-brown with darker mottling above and numerous whitish or yellow spots along the back, sides and original tail. The head is paler with greyish mottling and obscure pal streak from the front of the eye to the rear of mouth, and white upper eyelid. Underparts are white, and feet have narrow, tapering digits.[5] They have simple clawed feet with padded toes (five on each appendage). Beneath the pads are rows of broad plate-like scales, each covered by thousands of microscopic bristles with branched, flattened tips. These structures, called setae, provide an enormous surface contact area, and are believed to adhere to the molecular level.[6] It is distinguished from most other members of the genus by the combinations of two pre-anal pores; a single cloacal spur (post-anal tubercle) on each side; chin with a cluster of give enlarged scales, mental, first infralabial and postmental scales; a strong rostral groove; and distribution.[5]

Taxonomy

The genus was traditionally regarded as monotypic, with the single species of Rhynchoedura ornata named by Albert Gunther in 1867. In 2011 an extensive revision sampling of the population across Australia found overlooked genetic diversity in the genus and named four new cryptic species by Pepper, Doughty, Hutchinson and Keogh.[7] Each species is native to a specific perennial river drainage, and active rivers during wet periods of the Neogene could have led to allopatric speciation within the genus.

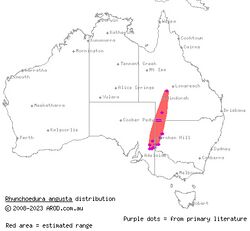

Distribution and habitat

Terrestrial geckos are mostly found on dry open terrain.[8] They occur in arid to semi-arid regions of central inland eastern Australia, from the Eyre Peninsula, SA, through the Lake Eyre basin to south-eastern NT and south-western QLD.[5] They are nocturnal and shelter in small, disused burrows, soil cracks, and under-leaf litter during the day.[9] They are most abundant in open and recently burned areas.[10][11]

Ecology

Like many desert-dwelling species, the Border beaked gecko has adapted to the harsh conditions of its environment. It can survive without water, obtaining moisture from its food instead.[12] In addition, their unique physical characteristics, such as their flattened bodies and sticky toes, allow them to move through rocky terrain quickly.[13] The diet of the border beaked gecko consists primarily of termites,[9] but they are also known to consume spiders and other small invertebrates at night.[14]

Being nocturnal, geckos usually indirectly source their heat, emerging from their retreats at dusk to forage on the sun-warmed substrate or in environments with suitable ambient temperatures.[15] They are subjected to lower and more uniform ambient temperatures than the thermal mosaic of sun and shade available to diurnal lizards. A study of Western Australian desert geckos showed that body temperatures of active lizards are usually slightly higher than the air temperature, with arboreal geckos tracking them most closely. Smaller gekkonid and diplodactylid species were found at most elevated temperatures (26°-27°C).[16]

Border beaked geckos are preyed upon by a range of larger animals, such as snakes, birds, and small mammals.[17] Camouflage is an effective means of avoiding predators.[18] They become almost invisible, which superbly replicates the backgrounds they rest on, and mimic the stones around them.

The tail autonomy of the border beaked gecko means it can discard a disposable body part to escape. They have a specific fracture plane, the soft tissue in the centres of the caudal vertebrae. When grasped by the tail, it can be released at pre-weakened cleavage points. It can control how much tail they lose.[19] This is efficient, as replacing a whole tail can be metabolically expensive, taxing a portion of food taken and potentially delaying reproductive success.[20]

They have clear spectacles covering their lidless eyes and use their broad flat tongues to keep them clean. The jacobson’s organ is a chromogenic chamber opening into the roof of the mouth, detecting odorant particles delivered by the tongue, and conveying sensory information to the brain via the olfactory nerve.[21] They can vocalize, but squeaks and chirrups are primarily used in moments of high stress – including social conflict, mating or attack by predators. When harassed, diplodactylid geckos rear and inflate their bodies.[19]

Life history

The border beaked gecko is known to mate during the summer and spring.[2] During the breeding season, males will actively seek out females, and male Border beaked geckos become territorial and will fight with other males for access to females. Mating almost always involves males biting females, usually around the nape, shoulder or forelimb area. If accommodating, the female relaxes in this grip and raises her hind body, allowing the male to twist under to access her cloaca.[19] The male has paired sex organs called hemipenes, lying in cavities at the base of the tail.[21] The female will lay a clutch of two oviparous soft, parchment-shelled eggs. The pale areas in the gecko’s neck contain calcium carbonate, which is used to strengthen the eggshell before the eggs are laid. They will hatch after an incubation period of around 60 days.[5] It cuts a small hole in the eggshell using a small egg tooth on the front of its jaw.[19] The hatchlings are fully independent and able to fend for themselves from birth. The infant survives on its absorbed yolk reserves during the first few days. When these reserves run out, it will start to hunt for insects.[19]

Evolutionary Relationships

The Diplodactyline geckos are believed to have originated in Australia around 35 million years ago. They are thought to have evolved from a common ancestor closely related to the Gekko genus, found in Asia.[22] In terms of the Border Beaked Gecko specifically, genetic analysis has revealed that it is most closely related to Rhynchoedura ornata, a species found in the Northern Territory of Australia. This suggests that the Border Beaked Gecko may have evolved from Rhynchoedura ornata or a common ancestor that the two species share.[7] This research has led to a greater understanding of the unique adaptations that have allowed the border beaked gecko to thrive in its environment. For example, the researchers have found that the gecko’s beak is ideally suited for capturing prey, allowing it to survive in hard conditions where food may be scarce.[7]

Conservation

The border beaked gecko is currently listed as a species of ‘Least Concern’ by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).[23] This is because the species' population is relatively stable and widespread across its range. It is still vulnerable to threats that are experienced by many reptile species in Australia. One of the biggest threats is habitat loss due to human activity, such as urbanization, mining, and agriculture. Climate change is also a significant threat, as it alters the environmental conditions that the species needs to survive. Introducing non-native species, such as cats and foxes has increased predation on the border beaked gecko.[19]

References

- ↑ "Rhynchoedura angusta". http://reptile-database.reptarium.cz/species?genus=Rhynchoedura&species=angusta&search_param=%28%28search%3D%27Rhynchoedura+angusta%27%29%29. Retrieved 2017-11-11.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Rowland, P., & Farrell, P. (2017). A naturalist’s guide to the reptiles of Australia. John Beaufoy.

- ↑ Johansen, T. (2012). A field guide to the geckos of Northern Territory. AuthorHouse.

- ↑ Wilson, S., & Swan, G. (1954). What lizard is that?: Introducing Australia lizards. Reed New Holland.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Cogger, H. (2014). Reptiles and amphibians of Australia (Seventh edition.). CSIRO Publishing.

- ↑ Autumn, K., Niewiarowski, P. H., & Puthoff, J. B. (2014). Gecko Adhesion as a Model System for Integrative Biology, Interdisciplinary Science, and Bioinspired Engineering. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 45(1), 445–470. doi:10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-120213-091839

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Pepper, M., Doughty, P., Hutchinson, M. N., & Scott Keogh, J. (2011). Ancient drainages divide cryptic species in Australia’s arid zone: Morphological and multi-gene evidence for four new species of Beaked Geckos (Rhynchoedura). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 61(3), 810–822. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2011.08.012

- ↑ Pianka, E. R., & Pianka, H. D. (1976). Comparative Ecology of Twelve Species of Nocturnal Lizards (Gekkonidae) in the Western Australian Desert. Copeia, 1976(1), 125–142. doi:10.2307/1443783

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Ehmann, H. (1992). Encyclopedia of Australian animals. Harper Collins.

- ↑ Letnic, M., Dickman, C. ., Tischler, M. ., Tamayo, B., & Beh, C.-L. (2004). The responses of small mammals and lizards to post-fire succession and rainfall in arid Australia. Journal of Arid Environments, 59(1), 85–114. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2004.01.014

- ↑ Pianka, E. R., & Goodyear, S. E. (2012). Lizard responses to wildfire in arid interior Australia: Long-term experimental data and commonalities with other studies. Austral Ecology, 37(1), 1–11. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.2010.02234.x

- ↑ Robertson, P., & Coventry, A. J. (2014). Reptiles of Victoria: a guide to identification and ecology. Csiro Publishing.

- ↑ Bauer, A. M. (1998). Morphology of the adhesive tail tips of carphodactyline geckos (Reptilia: Diplodactylidae). Journal of Morphology (1931), 235(1), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4687(199801)235:1<41::AID-JMOR4>3.0.CO;2-R

- ↑ Sass, S. (2006). The reptile fauna of Nombinnie Nature Reserve and State Conservation Area, western New South Wales. Australian Zoologist, 33(4), 511-518.

- ↑ Sievert, L. M., & Hutchison, V. H. (1988). Light versus Heat: Thermoregulatory Behavior in a Nocturnal Lizard (Gekko gecko). Herpetologica, 44(3), 266–273.

- ↑ Pianka, Eric R., and Helen D. Pianka. “Comparative Ecology of Twelve Species of Nocturnal Lizards (Gekkonidae) in the Western Australian Desert.” Copeia, vol. 1976, no. 1, 1976, pp. 125–42. JSTOR, doi:10.2307/1443783.

- ↑ Henle, K. (1990). Population Ecology and Life History of Three Terrestrial Geckos in Arid Australia. Copeia, 1990(3), 759–781. doi:10.2307/1446442

- ↑ Stevens, M., & Ruxton, G. D. (2019). The key role of behaviour in animal camouflage. Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 94(1), 116–134. doi:10.1111/brv.12438

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 Wilson, S. (2012). Australian lizards: A natural history. CSIRO publishing.

- ↑ Starostova, Z., Gvozdik, L., & Kratochvil, L. (2017). An energetic perspective on tissue regeneration: The costs of tail autotomy in growing geckos. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. Part A, Molecular & Integrative Physiology, 206, 82–86. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2017.01.015

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Pough, H., Jains, C., & Heiser, J. (2013). Vertebrate life (9th ed.). Pearson Education.

- ↑ Hickman, C. P., Roberts, L. S., Keen, S. L., Larson, A., & Eisenhour, D. J. (2012). Animal diversity (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ Queensland Government. (2023). Species profile - Rhynchoedura angusta (border beaked gecko). https://apps.des.qld.gov.au/species-search/details/?id=34159

Wikidata ☰ Q3429842 entry

|