Biology:Bullacephalus

| Bullacephalus Temporal range: Late Permian

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Suborder: | †Biarmosuchia |

| Family: | †Burnetiidae |

| Genus: | †Bullacephalus Rubidge and Kitching, 2003 |

| Species: | †B. jacksoni

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Bullacephalus jacksoni Rubidge and Kitching, 2003

| |

Bullacephalus is an extinct genus of biarmosuchian therapsids belonging to the family Burnetiidae. The type species B. jacksoni was named in 2003. It is known from a relatively complete skull and lower jaw, discovered in the Late Permian Tapinocephalus Assemblage Zone of the Beaufort Group of South Africa .[1] This genus of therapsida lived during the Late Permian period, approximately 250 million years ago. The name Bullacephalus comes from the Latin words "bullatus," meaning "bossed" or "knobbed," and "cephalus," meaning "head." This name refers to the distinctive bony knob on the top of the therapsid's skull, which contributes to the history of this genus. This stem based taxon includes Ictidorhinus or Hippasaurs. Bullacephalus can even be characterized as having a, “skull moderately to greatly pachyostotic; swollen boss present above the postorbital bar formed by the postfrontal and postorbital; deep linear sculpturing of the snout; exclusion of the jugal from the lateral temporal fenestra” (Day et al., 2016).[2] These Therapsids have spongy bone skull roof, palatal process of premaxilla are long, diverticulum of naris adding them to the Burnetiamorph. Furthermore, the discovery of Bullacephalus has helped to refine the taxonomic classification of therapsids. Prior to its discovery, there was uncertainty regarding the relationship between different groups of therapsids, particularly the Burnetiamorpha and the Biarmosuchia. However, the distinctive features of Bullacephalus suggest that it is a member of the Burnetiamorpha, and provides a bridge between this group and the Biarmosuchia. The discovery of Bullacephalus has also highlighted the importance of continued exploration and excavation in areas that have yielded few therapsid fossils. The Beaufort Group of South Africa, where Bullacephalus was discovered, has been an important site for therapsid fossils, but much of the area remains unexplored. Further discoveries in this region and other areas around the world may provide new insights into the evolution and diversification of therapsids, as well as other groups of extinct animals. These discoveries will also help to refine our understanding of the history of life on Earth and the processes that have shaped the diversity of organisms that exist today.

Geological/paleoenvironmental information and historical information and discovery

This species is known from a complete skull and lower jaw that was discovered during the fieldwork of the Lower Beaufort group in the southern Karoo of South Africa. The Beaufort Group rocks in South Africa are well-known for their abundant Permo-Triassic therapsid fossils, which have allowed for biostratigraphic subdivision of the group into eight assemblage zones. In 1993, during fieldwork for biostratigraphic research in the lower Beaufort Tapinocephalus Assemblage Zone, a well-preserved skull of a medium-sized therapsid was discovered. The skull shares similarities with representatives of the Burnetiidae, a clade of basal therapsids that has only two known genera, Burnetia and Proburnetia, each represented by only one specimen. The newly discovered skull provides important new information about this enigmatic group of therapsids and their phylogenetic position within the Therapsida.[3] While the limited amount of fossil material available has made it difficult to determine the exact relationships between Bullacephalus and other therapsids, its placement within the Burnetiamorpha suborder has shed some light on its evolutionary history. The Burnetiamorpha were a group of therapsids that appeared during the late Permian period and were widespread across Gondwana, the southern supercontinent that included present-day Africa, South America, Australia, India, and Antarctica. Bullacephalus is one of the most enigmatic members of this group, and its discovery has raised questions about the biogeography and evolutionary history of the Burnetiamorpha. (Liu, J., Rubidge, B., & Li, J., 2009).[4] Further research into the morphology, phylogenetics, and ecology of Bullacephalus and other Burnetiamorpha will likely continue to yield insights into the evolution of therapsids and the complex history of life on Earth.

Taxonomy

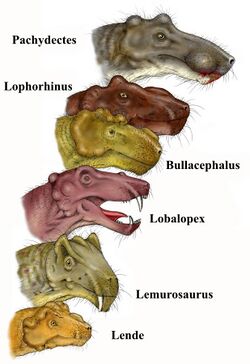

Despite the limited amount of fossil material available, Bullacephalus has generated considerable interest among paleontologists due to its unique morphology and uncertain taxonomic classification. It is a part of the Burnetiamorpha suborder. Currently, the Burnetiamorpha comprise nine genera: Bullacephalus, Burnetia, Lemurosaurus, Lobalopex, Lophorhinus, Paraburnetia, and Pachydectes from South Africa. (Kruger et al., 2015).[5] Some researchers have suggested that Bullacephalus are a type of Therapsida: Biarmoschia, related to the successful tetrapod Anomadontia helping researchers understand the basic morphology. This specific therapsid could be distinguished by the short snout, septomaxilla, and has a short facial exposure between nasal and maxilla, along with many other skull characteristics. Its unique morphology, particularly its short snout and septomaxilla, have led researchers to speculate about its feeding habits and ecological niche.

Description and paleobiology

The specimen of Bullacephalus is a moderately complete skull and lower jaw, with some missing anterior portions of the snout and lower jaw and badly weathered left side and skull roof posterior to the pineal foramen. The temporal opening is situated posteroventral to the orbit, and three pachyostosis bony bosses are present on the skull, similar to Burnetia and Proburnetia, but with a different appearance. The premaxilla is not preserved, but the remaining portion of the maxilla forms most of the side of the snout, exhibiting a rugose surface anteriorly and reaching the dorsal limit below the dorsomedially positioned nasal boss. The paired nasals do not have a large exposure on the skull roof, and the anterior portion is not preserved. The prefrontal is a large bone forming the anterodorsal and dorsal margins of the orbit, and above the orbit, it forms a prominent supraorbital boss, thinning anteriorly and extending to the lateral side of the skull as far as the nasal boss. The lacrimal has a large exposure anterior to the orbit, with a prominent rectangular fossa on its anterodorsal side bordering the prefrontal dorsally and the maxilla anteriorly. The zygomatic arch is thick and poorly defined, with unclear sutural contacts between the elements. The postorbital is narrow when viewed from the side, and its sutural borders are unclear.[6] The moderately complete skull and lower jaw of Bullacephalus provide valuable information about its morphology and classification. The position of the temporal opening, posteroventral to the orbit, is a common feature among therapsids, and the presence of three pachyostosis bony bosses is a distinguishing characteristic of Burnetiamorpha. The rugose surface of the anterior portion of the maxilla suggests that Bullacephalus may have had a powerful bite. The nasal boss and the prominent supraorbital boss of the prefrontal are also notable features of Bullacephalus' skull, which may have served as attachment points for powerful jaw muscles. The rectangular fossa on the anterodorsal side of the lacrimal is another interesting feature of Bullacephalus' skull. This fossa may have been a site of attachment for the lacrimal gland. Alternatively, it may have been a site of attachment for muscles that control the opening and closing of the eye.The poor definition of the zygomatic arch and the unclear sutural borders of the postorbital are areas where further study is needed. These features may provide additional clues about the evolutionary relationships between Bullacephalus and other therapsids. Despite the missing anterior portions of the snout and lower jaw, the moderately complete skull and lower jaw of Bullacephalus are still valuable specimens for understanding the morphology and classification of this unique therapsid. Further study of Bullacephalus and other Burnetiamorpha will undoubtedly shed more light on the evolutionary history of therapsids and the complex ecosystems in which they lived.

References

- Day, M. O., Smith, R. M., Benoit, J., Fernandez, V., & Rubidge, B. S. (2018). A new species of burnetiid (Therapsida, Burnetiamorpha) from the early wuchiapingian of South Africa and implications for the evolutionary ecology of the family Burnetiidae. Papers in Palaeontology, 4(3), 453–475. https://doi.org/10.1002/spp2.1114

- Day, M., Rubidge, B., & Abdala, F. (2016). A new mid-permian burnetiamorph therapsid from the main Karoo Basin of South Africa and a phylogenetic review of Burnetiamorpha. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 61. https://doi.org/10.4202/app.00296.2016

- Kruger, A., Rubidge, B. S., Abdala, F., Chindebvu, E. G., & Jacobs, L. L. (2015). lende chiweta, a new therapsid from Malawi, and its influence on Burnetiamorph phylogeny and biogeography. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 35(6). https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2015.1008698

- Sidor, C. A., & Welman, J. (2003). A second specimen oflemurosaurus pricei(therapsida: Burnetiamorpha). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 23(3), 631–642. https://doi.org/10.1671/0272-4634(2003)023[0631:assolp]2.0.co;2

- Sidor, C. A., Hopson, J. A., & Keyser, A. W. (2004). A new burnetiamorph therapsid from the Teekloof Formation, Permian, of South Africa. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 24(4), 938–950. https://doi.org/10.1671/0272-4634(2004)024[0938:anbtft]2.0.co;2

- Kammerer, C., & Sidor, C. (2020). A new burnetiid from the mid-permian of zambia and a reanalysis of Burnetiamorph Relationships (project). MorphoBank Datasets. https://doi.org/10.7934/p3785

- Rubidge, B. S., & Kitching, J. W. (2003). A new burnetiamorph (Therapsida: Biarmosuchia) from the Lower Beaufort Group of South Africa. Palaeontology, 46(1), 199–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4983.00294

- Liu, J., Rubidge, B., & Li, J. (2009). A new specimen of biseridens qilianicus indicates its phylogenetic position as the most basal anomodont. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 277(1679), 285–292. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.0883

- SIDOR, Christian. (2003). The Naris and palate of Lycaenodon longiceps (Therapsida: BIARMOSUCHIA), with comments on their early evolution in the Therapsida. Journal of Paleontology, 77(5), 977–984. https://doi.org/10.1666/0022-3360(2003)077<0977:tnapol>2.0.co;2

- Smith, R. M., Rubidge, B. S., & Sidor, C. A. (2006). A new burnetiid (Therapsida: Biarmosuchia) from the Upper Permian of South Africa and its biogeographic implications. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 26(2), 331–343. https://doi.org/10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[331:anbtbf]2.0.co;2

- ↑ Rubidge, B.S.; Kitching, J.W. (2003). "A new burnetiamorph (Therapsida: Biarmosuchia) from the Lower Beaufort Group of South Africa.". Palaeontology 46 (1): 199–210. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00294.

- ↑ Day, Michael; Rubidge, Bruce; Abdala, Fernando (2016). "A new mid-Permian burnetiamorph therapsid from the Main Karoo Basin of South Africa and a phylogenetic review of Burnetiamorpha.". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 61. doi:10.4202/app.00296.2016. ISSN 0567-7920. http://dx.doi.org/10.4202/app.00296.2016.

- ↑ Rubidge, Bruce S.; Kitching, James W. (January 2003). "A new burnetiamorph (Therapsida: Biarmosuchia) from the Lower Beaufort Group of South Africa". Palaeontology 46 (1): 199–210. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00294. ISSN 0031-0239. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1475-4983.00294.

- ↑ Liu, Jun; Rubidge, Bruce; Li, Jinling (2009-07-29). "A new specimen of Biseridens qilianicus indicates its phylogenetic position as the most basal anomodont". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 277 (1679): 285–292. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0883. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 2842672. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.0883.

- ↑ Kruger, Ashley; Rubidge, Bruce S.; Abdala, Fernando; Chindebvu, Elizabeth Gomani; Jacobs, Louis L. (2015-10-29). "Lende chiweta, a new therapsid from Malawi, and its influence on burnetiamorph phylogeny and biogeography". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 35 (6): e1008698. doi:10.1080/02724634.2015.1008698. ISSN 0272-4634. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2015.1008698.

- ↑ Rubidge, Bruce S.; Kitching, James W. (January 2003). "A new burnetiamorph (Therapsida: Biarmosuchia) from the Lower Beaufort Group of South Africa". Palaeontology 46 (1): 199–210. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00294. ISSN 0031-0239. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1475-4983.00294.

Wikidata ☰ Q4996667 entry

|