Biology:Cave swallow

| Cave swallow | |

|---|---|

| |

| near Rock Springs, Texas, USA | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Hirundinidae |

| Genus: | Petrochelidon |

| Species: | P. fulva

|

| Binomial name | |

| Petrochelidon fulva (Vieillot, 1808)

| |

| |

The cave swallow (Petrochelidon fulva) is a medium-sized, squarish-tailed swallow belonging to the same genus as the more familiar and widespread cliff swallow of North America. The cave swallow, also native to the Americas, nests and roosts primarily in caves and sinkholes.

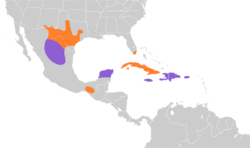

Cave swallows are found in Mexico and the Greater Antilles, with fall and winter vagrants reaching the east and Gulf Coasts of the United States Breeding colonies occur in south-eastern New Mexico, Texas , Florida, the Greater Antilles, portions of southern Mexico, and along the west coast of South America. Five subspecies are currently recognized according to Birds of North America, three occurring in North America and two in South America.[2]

Description

The cave swallow measures 12 to 14 cm in length and weighs 19 g on average. The largest of the five subspecies, P. f. pallida, has an average wing length between 107.0 and 112.3 mm; the smallest subspecies, P. f. aequatorialis, has an average wing length between 93.0 and 93.5 mm. Differences between the sexes are minimal, both are similar in size and weight and are difficult to distinguish from their plumage.[2] It has grey-blue upperparts and brown-tangerine forefront and throat.

Taxonomy

The cave swallow is a passerine belonging to the swallow and martin family, Hirundinidae. The genus Petrochelidon is a collection of cliff-nesting swallows and martins, though only the two South American subspecies prefer nesting on cliff-faces. The three North American subspecies prefer nesting in caves and sinkholes, as their common name suggests. Five subspecies of Petrochelidon fulva are currently recognized.[2]

The three North American subspecies are P. f. fulva, P. f. pallida, and P. f. citata. All three will usually nest in natural caves and sinkholes, or in some areas they will nest in or underneath man-made structures (highway culverts, under bridges, etc.).[2] All three have larger wing-spans than the remaining two South American subspecies. P. f. fulva occurs in the Greater Antilles and southern Florida. P. f. pallida (also known as P. f. pelodoma) is found farther west in the south-western United States and into north-eastern Mexico. P. f. citata has the southernmost range of the North American subspecies and is found on the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico.

The remaining two South American subspecies of the cave swallow are sometimes regarded as distinct species separate from the species fulva; not only is their range geographically separate from the North American subspecies but they also choose distinctly different nesting sites. Rather than nesting in caves and sinkholes, P. f. aequatorialis and P. f. rufocollaris nest in open areas, such as on cliff faces and the sides of buildings.[2] P. f. aequatorialis is found in Ecuador, and it is speculated that it may extend its range into Peru. P. f. rufocollaris occurs in north-western Peru. These two subspecies have smaller wingspans than their North American counterparts.

P. f. citata and P. f. pallida are generally accepted as distinct subspecies of P. fulva; however, cytochrome b and microsatellite data support an emerging consensus that P. f. rufocollaris should in fact be considered its own species within Petrochelidon.[3]

Habitat

During the breeding season, P. f. fulva, P. f. pallida, and P. f. citata, the North American subspecies of the cave swallow, will usually nest in a caves, sinkholes, and sometimes in man-made structures offering similar habitat, such as highway culverts. P. f. aequatorialis and P. f. rufocollaris, the South American subspecies, prefer to nest in open areas such as on cliff faces and the sides of buildings.

All subspecies of the cave swallow forage for insects over open areas and water nearby their roosting sites.[2] Their spring and fall migrations are poorly known; however, P. f. citata, P. f. aequatorialis and P. f. rufocollaris are considered resident species and winter in their breeding range.[2]

Distribution

P. f. pallida is found farther west in the south-western United States and into north-eastern Mexico. P. f. citata has the southernmost range of the North American subspecies and is found on the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico. P. f. aequatorialis is found in Ecuador, and it is speculated that it may extend its range into Peru. P. f. rufocollaris occurs in north-western Peru.

Breeding is known to occur in Mexico, south-eastern New Mexico, southern Florida, Greater Antilles and in areas of Texas. The South American populations, as well as most Mexican and Caribbean populations, are considered resident populations which breed and overwinter in the same geographic range. The New Mexico and other northern populations migrate south; however, it is not known where they migrate to or which migration routes they take. Cave swallows have been observed to overwinter in southern Texas since at least the 1980s.

Behaviour

Vocalizations

Cave swallow chicks begin giving faint calls shortly after hatching.[2] As the chicks develop their calls become louder and more aggressive. These calls allow the chicks to communicate to the attending parent(s) their basic needs, such as hunger.

There is currently no data regarding differences in vocalizations between the subspecies of cave swallows; however, the following descriptions are based on observations of P. f. pallida. Adults utilize five main vocalizations: a song, "che" note, and three types of chattering described by Selander and Baker (1957).[4]

- The cave swallow's song typically lasts 3–4 seconds and is described as a "series of squeaks that gradually blend into a 'complex melodic warble' and end in a series of double-toned notes in which a 'gua' sound and a very low 'nock' sound are given simultaneously."[2][4] Sometimes the song ends with a "sharp eep note."[2][4]

- A high-pitched, nasal "che" note is often given in response to the presence of predators in the nest area, other birds passing near the cave swallow's nest, or while the swallow is in flight.[2][4] It is the note given most frequently when the bird is away from its nest site.

- The first type of chattering is the most common, it is described as a "short, clear weet or cheweet given at medium pitch with an ascending or descending inflection."[2][4]

- The second type of chattering is given in response to predators, most often occurring in series of 2 to 4. It is described as "a high-pitched che or chu note."[2][4]

- The third type of chattering is the least commonly given and usually only when the bird has been disturbed. It is described as a "lower pitched, clearer choo with a descending inflection."[2][4]

Cave swallows are most often heard singing from March to August in Texas and New Mexico, corresponding more or less to their breeding season.[2] In general, birds are vocal throughout the day when their nesting colony is active; however, they are usually loud and vocal at their nest site, becoming quieter as they move away from their nest.

Diet and foraging behaviour

Cave swallows feed on small to medium-sized flying insects throughout the day. They forage in loose flocks over open areas, on open vegetation, and against cliff-faces. During the nesting season, adult cave swallows preferentially forage in the early hours of the morning and in the late afternoon. They capture a wide variety of insects during the nesting season, included species from the families Acrididae, Lygaeidae, Reduviidae, and others.[2] They drink while in flight by skimming the surface of pools and rivers.

A benefit to nesting in colonies could be the ability to share and procure information about food sources from neighbouring birds while raising chicks. While research has not been conducted on cave swallows themselves, some studies have been done on the closely related cliff and bank swallows. Cliff swallow nesting colonies have been suggested to serve as "information centres", where swallows can gather and glean information from one another regarding how well they are foraging.[5] Cliff swallows have been observed to follow, or be followed by, other birds within the nesting colony to food sources; birds that were unsuccessful foraging will return to the colony to find a fellow roost-mate that has been successful, and which they will then follow to a food source.[5] Bank swallows, however, do not appear to use small nesting colonies (26-52 nesting pairs is considered a small colony) as "information centres",[6] but the cliff swallow colonies previously mentioned were large colonies in which there are more potentially successful foragers for other birds to follow.

Reproduction

As previously mentioned, North American subspecies of cave swallows roost and nest primarily in caves and sinkholes while the South American subspecies prefer open spaces such as cliff-faces and the sides of buildings. Breeding occurs between April and August.[2][7] North American subspecies are currently undergoing a human-facilitated range expansion due to the increased availability of alternative nesting sites.[8][9] These include highway culverts and bridges. In Texas alone cave swallows have increased their breeding range 898% between 1957 and 1999, with populations increasing at a rate of about 10.8% each year.[8]

Cave swallows are open-cup nesters, meaning they build a nest shaped like a cup with the top left open for them to fly in and out. The nests are made of mud and bat guano and can be reused for multiple breeding seasons. Old barn swallow nests are also utilized by cave swallows, which will modify them to suit their needs. Barn swallows and cave swallows are observed to co-exist at some nesting sites,[9] making old barn swallow nests easily available to the cave swallow. Cave swallows are social and prefer to nest in variably sized colonies. They are even observed to occasionally share nest sites with other species of swallows, such as barn swallows. This occurs particularly often in north central Mexico and increasingly in the United States with the increased use of highway culverts as nesting sites.[9] Some concerns have been raised about the potential for, and instances of, interbreeding between the two species and the viability of the hybrids.[7][10]

While the use of human-made nesting sites has allowed the cave swallow to greatly increase its range across North America, it may come with its own risks. Culvert and bridge nesting sites have an increased risk of flooding the nest area, a more variable thermal regime during the breeding season, an increased instance of sharing the colony site with other species, an increased risk of nest predation, and fewer available nesting materials.[7] Caves and sinkholes, however, are not at great risk of flooding, have a less variable thermal regime, lower instance of sharing the site with other species, lower risk of predation, and easily available nesting materials.[7] All this being said, cave swallows nesting at the culvert site laid more eggs, had more eggs hatch, and had more nestlings survive than those nesting at Dunbar Cave in 1974, which could explain why the population is growing so rapidly while using a riskier nest site.[7]

Incubation behaviour and clutch characteristics

Cave swallow eggs are elliptical ovate in shape and typically white in colour with some variation of fine spotting of light to dark brown or even lilac and dull purple.[2] Clutches of three to five eggs are typical and both sexes are thought to contribute to the incubation of the clutch. Only the female is observed to develop a brood patch.[2]

Cave swallows are altricial when they hatch; they are blind and incapable of sustaining their own body heat.[2] They remain in the nest until they are capable of flying, which is approximately 20 to 22 days after hatching.[2] Both parents will feed the nestlings small insects throughout the day and will defend the nest if threatened by swooping and loudly calling at the threat.

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2019). "Petrochelidon fulva". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T22712435A137673174. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T22712435A137673174.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22712435/137673174. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 West, S. (1995). Cave Swallow (Hirundo fulva). In The Birds of North America, No. 141 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, and The American Ornithologists' Union, Washington, D.C.

- ↑ Kirchman, J. J., Whittingham, L. a, & Sheldon, F. H. (2000). Relationships among Cave Swallow Populations (Petrochelidon fulva) Determined by Comparisons of Microsatellite and Cytochrome b Data. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 14(1), 107-21. doi:10.1006/mpev.1999.0681.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Selander, R. K., & Baker, J. K. (1957). The Cave Swallow in Texas. The Condor, 59(November–December), 345-363.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Brown, C. R. (1986). Cliff Swallow Colonies as Information Centers. Science, 234(4772), 83-85.

- ↑ Stutchbury, B. J. (1988). Evidence That Bank Swallow Colonies Do Not Function as Information Centers. The Condor, 90(4), 953-955.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Martin, R. F. (1981). Reproductive correlates of environmental variation and niche expansion in the cave swallow in Texas. The Wilson Bulletin, 93(4), 506-518.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Kosciuch, K. L., Ormston, C. G., & Arnold, K. A. (2006). Breeding range expansion by Cave Swallows (Petrochelidon fulva) in Texas. The Southwestern Naturalist, 51(2), 203-209. doi:10.1894/0038-4909(2006)51.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Martin, R. F. (1974). Syntopic culvert nesting of Cave and Barn Swallows in Texas. The Auk, 91(October), 776-782.

- ↑ Martin, R. F. (1982). Proximate Ecology and Mechanics of "Intergeneric" Swallow Hybridization (Hirundo rustica × Petrochelidon fulva). The Southwestern Naturalist, 27(2), 218-220.

- Oberle, Mark (2003) (in es). Las aves de Puerto Rico en fotografías. Editorial Humanitas. ISBN 0-9650104-2-2.

External links

- http://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Cave_Swallow/id

- http://www.sibleyguides.com/bird-info/cave-swallow/

- http://xeno-canto.org/recording.php?XC=34112

- http://xeno-canto.org/recording.php?XC=27723

- http://ibc.lynxeds.com/species/cave-swallow-petrochelidon-fulva Cave swallow videos] on the Internet Bird Collection]

- Cave swallow photo gallery VIREO

Wikidata ☰ Q1587890 entry

|