Biology:Cell fusion

Cell fusion is an important cellular process in which several uninucleate cells (cells with a single nucleus) combine to form a multinucleate cell, known as a syncytium. Cell fusion occurs during differentiation of myoblasts, osteoclasts and trophoblasts, during embryogenesis, and morphogenesis.[1] Cell fusion is a necessary event in the maturation of cells so that they maintain their specific functions throughout growth.

History

In 1847 Theodore Schwann expanded upon the theory that all living organisms are composed of cells when he added that discrete cells are the basis of life. Schwann observed that in certain cells the walls and cavities of the cells coalesce together. This observation provided the first hint that cells fuse. It was not until 1960 that cell biologists deliberately fused cells for the first time. To fuse the cells, biologists combined isolated mouse cells and induced fusion of their outer membrane using the Sendai virus (a respiratory virus in mice). Each of the fused hybrid cells contained a single nucleus with chromosomes from both fusion partners. Synkaryon became the name of this type of cell combined with a nucleus. In the late 1960s biologists successfully fused cells of different types and from different species. The hybrid products of these fusions, heterokaryon, were hybrids that maintained two or more separate nuclei. This work was headed by Henry Harris at the University of Oxford and Nils Ringertz from Sweden's Karolinska Institute. These two men are responsible for reviving the interest of cell fusion. The hybrid cells interested biologists in the area of how different kinds of cytoplasm affect different kinds of nuclei. The work conducted by Henry and Nils showed that proteins from one gene fusion affect gene expression in the other partner's nucleus, and vice versa. These hybrid cells that were created were considered forced exceptions to normal cellular integrity and it was not until 2002 that the possibility of cell fusion between cells of different types may have a real function in mammals.[2]

Types of cell fusion

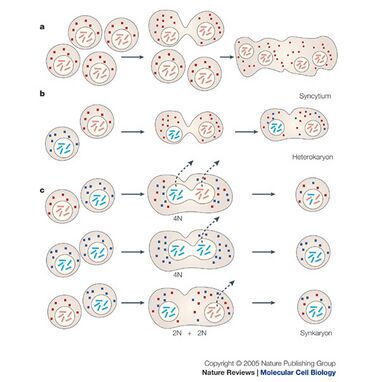

b Cells of different lineage fuse to form a cell with multiple nuclei, known as a heterokaryon. The fused cells might have undergone a reversion of phenotype or show transdifferentiation.

c Cells of different lineage or the same lineage fuse to form a cell with a single nucleus, known as a synkaryon. New functions of the fused cell can include a reversion of phenotype, transdifferentiation and proliferation. If nuclear fusion occurs, the fused nucleus initially contains the complete chromosomal content of both fusion partners (4N), but ultimately chromosomes are lost and/or re-sorted (see arrows). If nuclear fusion does not occur, a heterokaryon (or syncytium) can become a synkaryon by shedding an entire nucleus.

Homotypic cell fusion occurs between cells of the same type. An example of this would be osteoclasts or myofibers fusing together with their respective type of cells. When the two nuclei merge a synkaryon is produced. Cell fusion normally occurs with nuclear fusion, however in the absence of nuclear fusion, the cell would be described as a binucleated heterokaryon. A heterokaryon is the melding of two or more cells into one and it may reproduce itself for several generations.[3] If two of the same type of cells fuse but their nuclei do not fuse, then the resulting cell is called a syncytium.[4]

Heterotypic cell fusion occurs between cells of different types. The result of this fusion is also a synkaryon produced by the merging of the nuclei, and a binucleated heterokaryon in the absence of nuclear fusion. An example of this would be Bone Marrow Derived Cells (BMDCs) being fused with parenchymatous organs.[5]

Methods of cell fusion

There are four methods that cell biologists and biophysicists use to fuse cells. These four ways include electrical cell fusion, polyethylene glycol cell fusion, and sendai virus induced cell fusion and a newly developed method termed optically controlled thermoplasmonics.

Electrical cell fusion is an essential step in some of the most innovative methods in modern biology. This method begins when two cells are brought into contact by dielectrophoresis. Dielectrophoresis uses a high frequency alternating current, unlike electrophoresis in which a direct current is applied. Once the cells are brought together, a pulsed voltage is applied. The pulse voltage causes the cell membrane to permeate and subsequent combining of the membranes and the cells then fuse. After this, alternative voltage is applied for a brief period of time to stabilize the process. The result of this is that the cytoplasm has mixed together and the cell membrane has completely fused. All that remains separate is the nuclei, which will fuse at a later time within the cell, making the result a heterokaryon cell.[6]

Polyethylene glycol cell fusion is the simplest, but most toxic, way to fuse cells. In this type of cell fusion polyethylene glycol, PEG, acts as a dehydrating agent and fuses not only plasma membranes but also intracellular membranes. This leads to cell fusion since PEG induces cell agglutination and cell-to-cell contact. Though this type of cell fusion is the most widely used, it still has downfalls. Oftentimes PEG can cause uncontrollable fusion of multiple cells, leading to the appearance of giant polykaryons. Also, standard PEG cell fusion is poorly reproducible and different types of cells have various fusion susceptibilities. This type of cell fusion is widely used for the production of somatic cell hybrids and for nuclear transfer in mammalian cloning.[7]

Sendai virus induced cell fusion occurs in four different temperature stages. During the first stage, which lasts no longer than 10 minutes, viral adsorption takes place and the adsorbed virus can be inhibited by viral antibodies. The second stage, which is 20 minutes, is pH dependent and an addition of viral antiserum can still inhibit ultimate fusion. In the third, antibody-refractory stage, viral envelope constituents remain detectable on the surface of cells. During the fourth stage, cell fusion becomes evident and HA neuraminidase and fusion factor begin to disappear. The first and second stages are the only two that are pH dependent.[8]

Thermoplasmonics induced cell fusion Thermoplasmonics is based on a near infrared (NIR) laser and a plasmonic nanoparticle. The laser which typically acts as an optical trap, is used to heat the nanoscopic plasmonic particle to very high and extremely locally elevated temperatures. Optical trapping of such a nanoheater at the interface between two membrane vesicles, or two cells, leads to immediate fusion of the two verified by both content and lipid mixing. Advantages include full flexibility of which cells to fuse and fusion can be performed in any buffer condition unlike electroformation which is affected by salt.

In human therapy

Alternative forms of restoring organ function and replacing damaged cells are needed with donor organs and tissue for transplantation being so scarce. It is because of the scarcity that biologists have begun considering the potential for therapeutic cell fusion. Biologists have been discussing implications of the observation that cell fusion can occur with restorative effects following tissue damage or cell transplantation. Though using cell fusion for this is being talked about and worked on, there are still many challenges those who wish to implement cell fusion as a therapeutic tool face. These challenges include choosing the best cells to use for the reparative fusion, determining the best way to introduce the chosen cells into the desired tissue, discovering methods to increase the incidence of cell fusion, and ensuring that the resulting fusion products will function properly. If these challenges can be overcome then cell fusion may have therapeutic potential.[9]

Role in plant cells

In plants, cell fusion happens far less frequently compared to eukaryotic cells, however it does occur in some situations. Plant cells have evolved unique methods to fuse cells, largely in part due to the cell wall that surrounds plant cells. The cell wall in a plant cell will become altered prior to fusion, usually becoming thinner or even forming a bridge between cells that are about to fuse. Gamete fusion can also occur in plants. [10]

Role in cancer progression

Cell fusion has become an area of focus for research in cancer progression in humans. When multiple types of differentiated cells fuse, the resulting cell could potentially be polyploid. Polyploid cells can be unstable due to their different genetic combinations which can often result in the cell becoming diseased. Polyploid cells can also result in unscheduled endoreplication, a process when DNA is replicated within the cell without the cell dividing, which has been linked to cancer development because of the increase in genetic instability within the cell. Metastasis, the spreading of cancer cells to different areas of the body and one of the leading causes of cancer related death, is a process that is linked to cell fusion. Cells derived from bone marrow fuse with malignant tumor cells, creating cells that have traits of each parent cell. These fused, cancerous cells have migration capabilities inherited from the bone marrow derived cell (BMDC) that allow it to travel throughout the body.[11]

Microorganisms

Fungi

Plasmogamy is the stage of the sexual cycle of fungi in which two cells fuse together to share a common cytoplasm while bringing haploid nuclei from both partners together in the same cell.

Amoebozoa

Cell fusion (plasmogamy or syngamy) is a stage in the Amoebozoa sexual cycle.[12]

Bacteria

In Escherichia coli spontaneous zygogenesis (Z-mating) involves cell fusion, and appears to be a form of true sexuality in prokaryotes. Bacteria that perform Z-mating are called Szp+.[13]

Other uses

- To study the control of cell division and gene expression.

- To investigate malignant transformations.

- To obtain viral replication.

- For gene and chromosome mapping.

- For production of monoclonal antibodies by producing hybridoma.

- For production of induced stem cells.

- To assess protein shuttling in what is known as a heterokaryon fusion assay.[14]

See also

- Cell-cell fusogens

- Cellular differentiation

- Fertilisation

- Fusion mechanism

- Fusion protein

- Interbilayer forces in membrane fusion

- Lipid bilayer fusion

References

- ↑ "6.3. Cell fusion". Herkules.oulu.fi. http://herkules.oulu.fi/isbn9514269306/html/x1210.html.

- ↑ Ogle, Brenda M.; Platt, Jeffrey L. (1 January 2004). "The Biology of Cell Fusion: Cells of different types and from different species can fuse, potentially transferring disease, repairing tissues and taking part in development". American Scientist 92 (5): 420–427. doi:10.1511/2004.49.943.

- ↑ "Definition of Cell fusion". http://www.medterms.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=32440.

- ↑ Ogle, B. M.; Cascalho, M.; Platt, J. L. (2005). "Cells derived by fusion". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 6 (7): 567–575. doi:10.1038/nrm1678. PMID 15957005.

- ↑ Singec, Ilyas; Snyder, Evan Y. (2008). "Inflammation as a matchmaker: Revisiting cell fusion". Nature Cell Biology 10 (5): 503–505. doi:10.1038/ncb0508-503. PMID 18454127.

- ↑ "Principles And Applications Of Electrical Cell Fusion". http://www.biocompare.com/Application-Notes/42892-Principles-And-Applications-Of-Electrical-Cell-Fusion/.

- ↑ Pedrazzoli, Filippo; Chrysantzas, Iraklis; Dezzani, Luca; Rosti, Vittorio; Vincitorio, Massimo; Sitar, Giammaria (1 January 2011). "Cell fusion in tumor progression: the isolation of cell fusion products by physical methods". Cancer Cell International 11: 32. doi:10.1186/1475-2867-11-32. PMID 21933375.

- ↑ Wainberg, M. A.; Howe, C. (1 October 1973). "Factors Affecting Cell Fusion Induced by Sendai Virus". J Virol 12 (4): 937–939. doi:10.1128/JVI.12.4.937-939.1973. PMID 4359961.

- ↑ Sullivan, Stephen; Eggan, Kevin (1 January 2006). "The potential of cell fusion for human therapy". Stem Cell Rev 2 (4): 341–349. doi:10.1007/BF02698061. PMID 17848721.

- ↑ Maruyama, Daisuke; Ohtsu, Mina; Higashiyama, Tetsuya (2016-12-01). "Cell fusion and nuclear fusion in plants". Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. The Rhomboid Superfamily in Development and Disease 60: 127–135. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.07.024. ISSN 1084-9521. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1084952116302282.

- ↑ Bastida-Ruiz, Daniel; Van Hoesen, Kylie; Cohen, Marie (April 2016). "The Dark Side of Cell Fusion" (in en). International Journal of Molecular Sciences 17 (5): 638. doi:10.3390/ijms17050638. ISSN 1422-0067. PMID 27136533.

- ↑ "Comparative Genomics Supports Sex and Meiosis in Diverse Amoebozoa". Genome Biol Evol 10 (11): 3118–3128. November 2018. doi:10.1093/gbe/evy241. PMID 30380054.

- ↑ "Spontaneous zygogenesis in Escherichia coli, a form of true sexuality in prokaryotes". Microbiology (Reading, Engl.) 149 (Pt 9): 2571–84. September 2003. doi:10.1099/mic.0.26348-0. PMID 12949181.

- ↑ Gammal, Roseann; Baker, Krista; Heilman, Destin (2011). "Heterokaryon Technique for Analysis of Cell Type-specific Localization". Journal of Visualized Experiments (49): 2488. doi:10.3791/2488. ISSN 1940-087X. PMID 21445034.

Further reading

| Library resources about Cell fusion |

- H. Harris: Cell fusion, 1970, Harvard University Press, Mass.

- Gordon, S (1975). "Cell fusion and some subcellular properties of heterokaryons and hybrids". The Journal of Cell Biology 67 (2): 257–280. doi:10.1083/jcb.67.2.257. PMID 1104638.

|