Biology:Amoebozoa

| Amoebozoa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chaos carolinensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| (unranked): | Amorphea |

| Phylum: | Amoebozoa Lühe, 1913 emend. Cavalier-Smith, 1998[3] |

| Clades[4][5] | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Amoebozoa is a major taxonomic group containing about 2,400 described species of amoeboid protists,[7] often possessing blunt, fingerlike, lobose pseudopods and tubular mitochondrial cristae.[6][8] In traditional classification schemes, Amoebozoa is usually ranked as a phylum within either the kingdom Protista[9] or the kingdom Protozoa.[10][11] In the classification favored by the International Society of Protistologists, it is retained as an unranked "supergroup" within Eukaryota.[6] Molecular genetic analysis supports Amoebozoa as a monophyletic clade. Modern studies of eukaryotic phylogenetic trees identify it as the sister group to Opisthokonta, another major clade which contains both fungi and animals as well as several other clades comprising some 300 species of unicellular eukaryotes.[7][8] Amoebozoa and Opisthokonta are sometimes grouped together in a high-level taxon, variously named Unikonta,[10] Amorphea[6] or Opimoda.[12]

Amoebozoa includes many of the best-known amoeboid organisms, such as Chaos, Entamoeba, Pelomyxa and the genus Amoeba itself. Species of Amoebozoa may be either shelled (testate) or naked, and cells may possess flagella. Free-living species are common in both salt and freshwater as well as soil, moss and leaf litter. Some live as parasites or symbionts of other organisms, and some are known to cause disease in humans and other organisms.

While the majority of amoebozoan species are unicellular, the group also includes several clades of slime molds, which have a macroscopic, multicellular stage of life during which individual amoeboid cells remain together after multiple cell division to form a macroscopic plasmodium or, in cellular slime molds, aggregate to form one.

Amoebozoa vary greatly in size. Some are only 10–20 μm in diameter, while others are among the largest protozoa. The well-known species Amoeba proteus, which may reach 800 μm in length, is often studied in schools and laboratories as a representative cell or model organism, partly because of its convenient size. Multinucleate amoebae like Chaos and Pelomyxa may be several millimetres in length, and some multicellular amoebozoa, such as the "dog vomit" slime mold Fuligo septica, can cover an area of several square meters.[13]

Morphology

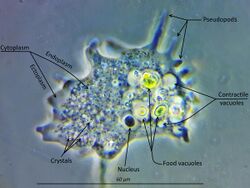

Amoebozoa is a large and diverse group, but certain features are common to many of its members. The amoebozoan cell is typically divided into a granular central mass, called endoplasm, and a clear outer layer, called ectoplasm. During locomotion, the endoplasm flows forwards and the ectoplasm runs backwards along the outside of the cell. In motion, many amoebozoans have a clearly defined anterior and posterior and may assume a "monopodial" form, with the entire cell functioning as a single pseudopod. Large pseudopods may produce numerous clear projections called subpseudopodia (or determinate pseudopodia), which are extended to a certain length and then retracted, either for the purpose of locomotion or food intake. A cell may also form multiple indeterminate pseudopodia, through which the entire contents of the cell flow in the direction of locomotion. These are more or less tubular and are mostly filled with granular endoplasm. The cell mass flows into a leading pseudopod, and the others ultimately retract, unless the organism changes direction.[14]

While most amoebozoans are "naked," like the familiar Amoeba and Chaos, or covered with a loose coat of minute scales, like Cochliopodium and Korotnevella, members of the order Arcellinida form rigid shells, or tests, equipped with a single aperture through which the pseudopods emerge. Arcellinid tests may be secreted from organic materials, as in Arcella, or built up from collected particles cemented together, as in Difflugia.

In all amoebozoa, the primary mode of nutrition is phagocytosis, in which the cell surrounds potential food particles with its pseudopods, sealing them into vacuoles within which they may be digested and absorbed. Some amoebozoans have a posterior bulb called a uroid, which may serve to accumulate waste, periodically detaching from the rest of the cell.[citation needed] When food is scarce, most species can form cysts, which may be carried aerially and introduce them to new environments.[citation needed] In slime moulds, these structures are called spores, and form on stalked structures called fruiting bodies or sporangia. Mixotrophic species living in a symbiotic relationship with microalgae of the genus Chlorella, which lives inside the cytoplasm of their host, have been found in Arcellinida and Mayorella.[15][16]

The majority of Amoebozoa lack flagella and more generally do not form microtubule-supported structures except during mitosis. However, flagella do occur among the Archamoebae, and many slime moulds produce biflagellate gametes [citation needed]. The flagellum is generally anchored by a cone of microtubules, suggesting a close relationship to the opisthokonts. [citation needed] The mitochondria in amoebozoan cells characteristically have branching tubular cristae. However, among the Archamoebae, which are adapted to anoxic or microaerophilic habitats, mitochondria have been lost.

Classification

Place of Amoebozoa in the eukaryote tree

It appears (based on molecular genetics) that the members of Amoebozoa form a sister group to animals and fungi, diverging from this lineage after it had split from the other groups,[17] as illustrated below in a simplified diagram:

| Opimoda |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Strong similarities between Amoebozoa and Opisthokonts lead to the hypothesis that they form a distinct clade.[18] Thomas Cavalier-Smith proposed the name "unikonts" (formally, Unikonta) for this branch, whose members were believed to have been descended from a common ancestor possessing a single emergent flagellum rooted in one basal body.[1][2] However, while the close relationship between Amoebozoa and Opisthokonta is robustly supported, recent work has shown that the hypothesis of a uniciliate ancestor is probably false. In their Revised Classification of Eukaryotes (2012), Adl et al. proposed Amorphea as a more suitable name for a clade of approximately the same composition, a sister group to the Diaphoretickes.[6] More recent work places the members of Amorphea together with the malawimonids and collodictyonids in a proposed clade called Opimoda, which comprises one of two major lineages diverging at the root of the eukaryote tree of life, the other being Diphoda.[12]

Subphyla within Amoebozoa: Lobosa and Conosa

Traditionally all amoebozoa with lobose pseudopods were grouped together in the class Lobosea, placed with other amoeboids in the phylum Sarcodina or Rhizopoda, but these were considered to be unnatural groups. Structural and genetic studies identified the percolozoans and several archamoebae as independent groups. In phylogenies based on rRNA their representatives were separate from other amoebae, and appeared to diverge near the base of eukaryotic evolution, as did most slime molds.

However, revised trees by Cavalier-Smith and Chao in 1996[19] suggested that the remaining lobosans do form a monophyletic group, to which the Archamoebae and Mycetozoa were closely related, although the percolozoans were not. Subsequently, they emended the phylum Amoebozoa to include both the subphylum Lobosa and a new subphylum Conosa, comprising the Archamoebae and the Mycetozoa.[3]

Recent molecular genetic data appear to support this primary division of the Amoebozoa into Lobosa and Conosa.[8] The former, as defined by Cavalier-Smith and his collaborators, consists largely of the classic Lobosea: non-flagellated amoebae with blunt, lobose pseudopods (Amoeba, Acanthamoeba, Arcella, Difflugia etc.). The latter is made up of both amoeboid and flagellated cells, characteristically with more pointed or slightly branching subpseudopodia (Archamoebae and the Mycetozoan slime molds).

Phylogeny and taxonomy within Amoebozoa

From older studies by Cavalier-Smith, Chao & Lewis 2016[20] and Silar 2016.[21] Also recent phylogeny indicates the Lobosa are paraphyletic: Conosa is sister of the Cutosea.[5][22][23]

| Amoebozoa phylogeny | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Phylum Amoebozoa Lühe 1913 emend. Cavalier-Smith 1998 [Amoebobiota; Eumycetozoa Zopf 1884 emend Olive 1975]

- Clade Discosea Cavalier-Smith 2004 stat. nov. Adl et al. 2018

- Order ?Stereomyxida Grell 1971

- Order ?Stygamoebida Smirnov & Cavalier-Smith 2011

- Class Centramoebia Cavalier-Smith et al. 2016

- Order Centramoebida Rogerson & Patterson 2002 em. Cavalier-Smith 2004

- Order Himatismenida Page 1987 [Cochliopodiida]

- Order Pellitida Page 1987 [Cochliopodiida]

- Class Flabellinia Smirnov & Cavalier-Smith 2011 em. Kudryavtsev et al. 2014

- Order Thecamoebida Schaeffer 1926 em. Smirnov & Cavalier-Smith 2011

- Order Dermamoebida Cavalier-Smith 2004 em. Smirnov & Cavalier-Smith 2011

- Order Vannellida Smirnov et al. 2005

- Order Dactylopodida Smirnov et al. 2005

- Clade Tevosa Kang et al. 2017

- Clade Tubulinea Smirnov et al. 2005 stat. nov. Adl et al. 2018

- Class Corycidia Kang et al. 2017 stat. nov. Adl et al. 2018

- Order Trichosida Moebius 1889

- Family Microcoryciidae de Saedeleer 1934

- Class Echinamoebia Cavalier-Smith 2016 stat. nov. Adl et al. 2018

- Order Echinamoebida Cavalier-Smith 2004 em. 2011

- Class Elardia Kang et al. 2017 stat. nov. Adl et al. 2018

- Subclass Leptomyxia Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Order Leptomyxida Pussard & Pons 1976 em. Page 1987

- Subclass Eulobosia Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Order Euamoebida Lepşi 1960 em. Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Order Arcellinida Kent 1880

- Subclass Leptomyxia Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Class Corycidia Kang et al. 2017 stat. nov. Adl et al. 2018

- Clade Evosea Kang et al. 2017 stat. nov. Adl et al. 2018

- Clade Cutosa Cavalier-Smith 2016 stat. nov.

- Class Cutosea Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Order Squamocutida Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Class Cutosea Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Subphylum Conosa Cavalier-Smith 1998 stat. nov.

- Infraphylum Archamoebae Cavalier-Smith 1993 stat. n. 1998

- Class Archamoebea Cavalier-Smith 1983 stat. n. 2004

- Family Tricholimacidae Cavalier-Smith 2013

- Family Endamoebidae Calkins 1926

- Order Entamoebida Cavalier-Smith 1993

- Order Pelobiontida Page 1976 emend. Cavalier Smith 1987

- Class Archamoebea Cavalier-Smith 1983 stat. n. 2004

- Infraphylum Semiconosia Cavalier-Smith 2013

- Class Variosea Cavalier-Smith et al. 2004

- Order ?Flamellidae Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Order ?Holomastigida Lauterborn 1895 [Artodiscida Cavalier-Smith 2013]

- Order Phalansteriida Hibberd 1983

- Order Ramamoebida Cavalier-Smith 2016

- Order Profiliida Kang et al. 2017 [Protosteliida Olive & Stoianovitch 1966 em. Shadwick & Spiegel 2012]

- Order Fractovitellida Lahr et al. 2011 em. Kang et al. 2017

- Superclass Mycetozoa de Bary, 1859 ex Rostafinski, 1873

- Class Dictyostelea Hawksworth et al. 1983

- Order Acytosteliales Baldauf, Sheikh & Thulin 2017

- Order Dictyosteliales Lister 1909 em. Olive 1970

- Class Ceratiomyxomycetes Hawksworth, Sutton & Ainsworth 1983

- Order Protosporangiida Shadwick & Spiegel 2012

- Order Ceratiomyxida Martin 1961 ex Farr & Alexopoulos

- Class Myxomycetes Link 1833 em. Haeckel 1866 [24]

- Subclass Lucisporomycetidae Leontyev et al. 2019

- Superorder Cribrarianae Leontyev 2015

- Order Cribrariales Macbr. 1922

- Superorder Trichianae Leontyev 2015

- Order Reticulariales Leontyev 2015

- Order Liceales Jahn 1928

- Order Trichiales Macbride 1922

- Superorder Cribrarianae Leontyev 2015

- Subclass Columellomycetidae Leontyev et al. 2019

- Order ?Echinosteliopsidales Shchepin et al.

- Superorder Echinostelianae Leontyev 2015

- Order Echinosteliales Martin 1961

- Superorder Stemonitanae Leontyev 2015 [Fuscisporida Cavalier-Smith 2012]

- Order Clastodermatales Leontyev 2015

- Order Meridermatales Leontyev 2015

- Order Stemonitales Macbride 1922

- Order Physarales Macbride 1922

- Subclass Lucisporomycetidae Leontyev et al. 2019

- Class Dictyostelea Hawksworth et al. 1983

- Class Variosea Cavalier-Smith et al. 2004

- Infraphylum Archamoebae Cavalier-Smith 1993 stat. n. 1998

- Clade Cutosa Cavalier-Smith 2016 stat. nov.

- Clade Tubulinea Smirnov et al. 2005 stat. nov. Adl et al. 2018

Fossil record

Vase-shaped microfossils (VSMs) discovered around the world show that amoebozoans have existed since the Neoproterozoic Era. The fossil species Melanocyrillium hexodiadema, Palaeoarcella athanata, and Hemisphaeriella ornata come from rocks 750 million years old. All three VSMs share a hemispherical shape, invaginated aperture, and regular indentations, that strongly resemble modern arcellinids, which are shell-bearing amoebozoans belonging to the class Tubulinea. P. athanata in particular looks the same as the extant genus Arcella.[1][25]

List of amoebozoan protozoa pathogenic to humans

Meiosis

The recently available Acanthamoeba genome sequence revealed several orthologs of genes employed in meiosis of sexual eukaryotes. These genes included Spo11, Mre11, Rad50, Rad51, Rad52, Mnd1, Dmc1, Msh and Mlh.[26] This finding suggests that Acanthamoeba is capable of some form of meiosis and may be able to undergo sexual reproduction.

In sexually reproducing eukaryotes, homologous recombination (HR) ordinarily occurs during meiosis. The meiosis-specific recombinase, Dmc1, is required for efficient meiotic HR, and Dmc1 is expressed in Entamoeba histolytica.[27] The purified Dmc1 from E. histolytica forms presynaptic filaments and catalyzes ATP-dependent homologous DNA pairing and DNA strand exchange over at least several thousand base pairs.[27] The DNA pairing and strand exchange reactions are enhanced by the eukaryotic meiosis-specific recombination accessory factor (heterodimer) Hop2-Mnd1.[27] These processes are central to meiotic recombination, suggesting that E. histolytica undergoes meiosis.[27]

Studies of Entamoeba invadens found that, during the conversion from the tetraploid uninucleate trophozoite to the tetranucleate cyst, homologous recombination is enhanced.[28] Expression of genes with functions related to the major steps of meiotic recombination also increased during encystations.[28] These findings in E. invadens, combined with evidence from studies of E. histolytica indicate the presence of meiosis in the Entamoeba. A comparative genetic analysis indicated that meiotic processes are present in all major amoebozoan lineages.[29]

Since Amoebozoa diverged early from the eukaryotic family tree, these results also suggest that meiosis was present early in eukaryotic evolution.

Human health

Amoebiasis, also known as amebiasis or entamoebiasis,[30][31] is an infection caused by any of the amoebozoans of the Entamoeba group. Symptoms are most common upon infection by Entamoeba histolytica. Amoebiasis can present with no, mild, or severe symptoms. Symptoms may include abdominal pain, mild diarrhoea, bloody diarrhea or severe colitis with tissue death and perforation. This last complication may cause peritonitis. People affected may develop anemia due to loss of blood.[32]

Invasion of the intestinal lining causes amoebic bloody diarrhea or amoebic colitis. If the parasite reaches the bloodstream it can spread through the body, most frequently ending up in the liver where it causes amoebic liver abscesses. Liver abscesses can occur without previous diarrhea. Cysts of Entamoeba can survive for up to a month in soil or for up to 45 minutes under fingernails. It is important to differentiate between amoebiasis and bacterial colitis. The preferred diagnostic method is through faecal examination under microscope, but requires a skilled microscopist and may not be reliable when excluding infection. This method however may not be able to separate between specific types. Increased white blood cell count is present in severe cases, but not in mild ones. The most accurate test is for antibodies in the blood, but it may remain positive following treatment.[32]

Prevention of amoebiasis is by separating food and water from faeces and by proper sanitation measures. There is no vaccine. There are two treatment options depending on the location of the infection. Amoebiasis in tissues is treated with either metronidazole, tinidazole, nitazoxanide, dehydroemetine or chloroquine, while luminal infection is treated with diloxanide furoate or iodoquinoline. For treatment to be effective against all stages of the amoeba may require a combination of medications. Infections without symptoms do not require treatment but infected individuals can spread the parasite to others and treatment can be considered. Treatment of other Entamoeba infections apart from E. histolytica is not needed.[32]

Amoebiasis is present all over the world.[33] About 480 million people are infected with what appears to be E. histolytica and these result in the death of between 40,000–110,000 people every year. Most infections are now ascribed to E. dispar. E. dispar is more common in certain areas and symptomatic cases may be fewer than previously reported. The first case of amoebiasis was documented in 1875 and in 1891 the disease was described in detail, resulting in the terms amoebic dysentery and amoebic liver abscess. Further evidence from the Philippines in 1913 found that upon ingesting cysts of E. histolytica volunteers developed the disease. It has been known since 1897 that at least one non-disease-causing species of Entamoeba existed (Entamoeba coli), but it was first formally recognized by the WHO in 1997 that E. histolytica was two species, despite this having first been proposed in 1925. In addition to the now-recognized E. dispar evidence shows there are at least two other species of Entamoeba that look the same in humans - E. moshkovskii and Entamoeba bangladeshi. The reason these species haven't been differentiated until recently is because of the reliance on appearance.[32]

Gallery

-

Arcella sp. test (Lobosa: Tubulinea)

-

Acanthamoeba sp. (Lobosa: Discosea)

-

Thecamoeba sp. (Lobosa: Discosea)

-

Pelomyxa palustris (Conosa: Archamoebae)

-

Stemonitis sp. (Conosa: Myxogastria)

-

Dictyostelium discoideum (Conosa: Dictyostelia)

Notes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Vase-shaped microfossils from the Neoproterozoic Chuar Group, Grand Canyon: a classification guided by modern testate amoebae". Journal of Paleontology 77 (3): 409–429. May 2003. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2003)077<0409:VMFTNC>2.0.CO;2. http://www.geol.ucsb.edu/faculty/porter/Papers/Porteretal2003_VSMs.pdf.

- ↑ "Estimating the timing of early eukaryotic diversification with multigene molecular clocks". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108 (33): 13624–9. August 2011. doi:10.1073/pnas.1110633108. PMID 21810989. Bibcode: 2011PNAS..10813624P.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "A revised six-kingdom system of life". Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 73 (3): 203–66. August 1998. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1998.tb00030.x. PMID 9809012.

- ↑ "Revisions to the Classification, Nomenclature, and Diversity of Eukaryotes". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 66 (1): 4–119. 2019. doi:10.1111/jeu.12691. PMID 30257078.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Between a Pod and a Hard Test: The Deep Evolution of Amoebae". Molecular Biology and Evolution 34 (9): 2258–2270. September 2017. doi:10.1093/molbev/msx162. PMID 28505375.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 "The revised classification of eukaryotes". The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 59 (5): 429–93. September 2012. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2012.00644.x. PMID 23020233.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "CBOL protist working group: barcoding eukaryotic richness beyond the animal, plant, and fungal kingdoms". PLOS Biology 10 (11): e1001419. November 6, 2012. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001419. PMID 23139639.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "Multigene phylogeny resolves deep branching of Amoebozoa". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 83: 293–304. February 2015. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2014.08.011. PMID 25150787.

- ↑ Corliss, John O. (1984). "The Kingdom Protista and its 45 Phyla". BioSystems 17 (2): 87–126. doi:10.1016/0303-2647(84)90003-0. PMID 6395918.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (2003). "Protist phylogeny and the high-level classification of Protozoa". European Journal of Protistology 39 (4): 338–348. doi:10.1078/0932-4739-00002.

- ↑ Ruggiero, Michael A.; Gordon, Dennis P.; Orrell, Thomas M.; Bailly, Nicolas; Bourgoin, Thierry; Brusca, Richard C.; Cavalier-Smith, Thomas; Guiry, Michael D. et al. (2015-06-11). "Correction: A Higher Level Classification of All Living Organisms". PLOS ONE 10 (6): e0130114. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0130114. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 26068874.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Bacterial proteins pinpoint a single eukaryotic root". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112 (7): E693–9. February 2015. doi:10.1073/pnas.1420657112. PMID 25646484. Bibcode: 2015PNAS..112E.693D.

- ↑ "Zinc accumulation by the slime mold Fuligo septica (L.) Wiggers in the former Soviet Union and North Korea". Journal of Environmental Quality 31 (3): 1038–42. 2002. doi:10.2134/jeq2002.1038. PMID 12026071.

- ↑ Jeon, Kwang W. (1973). Biology of Amoeba. New York: Academic Press. pp. 100. ISBN 978-0-323-14404-9. https://archive.org/details/biologyofamoeba0000jeon.

- ↑ Hoshina, Ryo; Tsukii, Yuuji; Harumoto, Terue; Suzaki, Toshinobu (February 2021). "Characterization of a green Stentor with symbiotic algae growing in an extremely oligotrophic environment and storing large amounts of starch granules in its cytoplasm". Scientific Reports 11 (2865). doi:10.1038/s41598-021-82416-9. PMID 33536497.

- ↑ Weiner, Agnes K.M.; Cullison, Billie; Date, Shailesh V.; Tyml, Tomáš; Volland, Jean-Marie; Woyke, Tanja; Katz, Laura A.; Sleith, Robin S. (February 2022). "Examining the Relationship Between the Testate Amoeba Hyalosphenia papilio (Arcellinida, Amoebozoa) and its Associated Intracellular Microalgae Using Molecular and Microscopic Methods". Protist 173 (1): 125853. doi:10.1016/j.protis.2021.125853. PMID 35030517.

- ↑ "The genome of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum". Nature 435 (7038): 43–57. May 2005. doi:10.1038/nature03481. PMID 15875012. Bibcode: 2005Natur.435...43E.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard; Wong, Yan (2016). The Ancestor's Tale. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0544859937.

- ↑ "Molecular phylogeny of the free-living archezoan Trepomonas agilis and the nature of the first eukaryote". Journal of Molecular Evolution 43 (6): 551–62. December 1996. doi:10.1007/BF02202103. PMID 8995052. Bibcode: 1996JMolE..43..551C.

- ↑ "187-gene phylogeny of protozoan phylum Amoebozoa reveals a new class (Cutosea) of deep-branching, ultrastructurally unique, enveloped marine Lobosa and clarifies amoeba evolution". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 99: 275–296. June 2016. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2016.03.023. PMID 27001604.

- ↑ Silar, Philippe (2016). "Protistes Eucaryotes: Origine, Evolution et Biologie des Microbes Eucaryotes". HAL archives-ouvertes. Creative Commons. pp. 1–462. ISBN 978-2-9555841-0-1. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01263138/file/Protistes_Eucaryotes.pdf.

- ↑ "First multigene analysis of Archamoebae (Amoebozoa: Conosa) robustly reveals its phylogeny and shows that Entamoebidae represents a deep lineage of the group". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 98: 41–51. May 2016. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2016.01.011. PMID 26826602.

- ↑ Leontyev, Dmitry V.; Schnittler, Martin; Stephenson, Steven L.; Novozhilov, Yuri K.; Shchepin, Oleg N. (March 2019). "Towards a phylogenetic classification of the Myxomycetes". Phytotaxa 399 (3): 209–238. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.399.3.5.

- ↑ Wijayawardene, Nalin; Hyde, Kevin; Al-Ani, LKT; Dolatabadi, S; Stadler, Marc; Haelewaters, Danny et al. (2020). "Outline of Fungi and fungus-like taxa". Mycosphere 11: 1060–1456. doi:10.5943/mycosphere/11/1/8.

- ↑ Porter, Susannah M. (2006). "The Proterozoic Fossil Record of Heterotrophic Eukaryotes". in Xiao, Shuhai; Kaufman, Alan J.. Neoproterozoic Geolobiology and Paleobiology. Topics in Geobiology. 27. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. pp. 1–21. doi:10.1007/1-4020-5202-2. ISBN 978-1-4020-5201-9.

- ↑ "Is there evidence of sexual reproduction (meiosis) in Acanthamoeba?". Pathogens and Global Health 109 (4): 193–5. June 2015. doi:10.1179/2047773215Y.0000000009. PMID 25800982.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 "Entamoeba histolytica Dmc1 Catalyzes Homologous DNA Pairing and Strand Exchange That Is Stimulated by Calcium and Hop2-Mnd1". PLOS ONE 10 (9): e0139399. 2015. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0139399. PMID 26422142. Bibcode: 2015PLoSO..1039399K.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "Homologous recombination occurs in Entamoeba and is enhanced during growth stress and stage conversion". PLOS ONE 8 (9): e74465. 2013. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0074465. PMID 24098652. Bibcode: 2013PLoSO...874465S.

- ↑ "Comparative genomics supports sex and meiosis in diverse Amoebozoa". Genome Biol Evol 10 (11): 3118–3128. November 2018. doi:10.1093/gbe/evy241. PMID 30380054.

- ↑ "Entamoebiasis - MeSH - NCBI". https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/68004749.

- ↑ "Entamoebiasis". http://mesh.kib.ki.se/swemesh/brs.cfm?Term=Entamoebiasis.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 Farrar, Jeremy; Hotez, Peter; Junghanss, Thomas; Kang, Gagandeep; Lalloo, David; White, Nicholas J. (2013-10-26). Manson's Tropical Diseases. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 664–671. ISBN 978-0-7020-5306-1.

- ↑ Beeching, Nick; Gill, Geoff (2014-04-17). "19". Lecture Notes: Tropical Medicine. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 177–182. ISBN 978-1-118-73456-8.

Further reading

- "The Amoebozoa". Dictyostelium discoideum Protocols. Methods in Molecular Biology. 983. 2013. pp. 1–15. doi:10.1007/978-1-62703-302-2_1. ISBN 978-1-62703-301-5.

External links

- Pawlowski, Jan. "Molecular Phylogeny of Amoeboid Protists — Tree of Amoebozoa". Molecular Systematics Group (MSG). Department of Zoology and Animal Biology, University of Geneva. http://www.unige.ch/sciences/biologie/biani/msg/Amoeboids/Amoebozoa.html.

- Keeling, Patrick; Leander, Brian S.; Simpson, Alastair. "Tree of Life Eukaryotes". Tree of Life Project. http://tolweb.org/Eukaryotes/3.

- Leidy, Joseph (1879). "Amoeba Plates". Fresh-Water Rhizopods of North America. Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office. http://user.xmission.com/~psneeley/Personal/FwrPLA.htm.

- Amoebozoa at UniEuk Taxonomy App.

Wikidata ☰ Q473809 entry

|