Biology:Colored dissolved organic matter

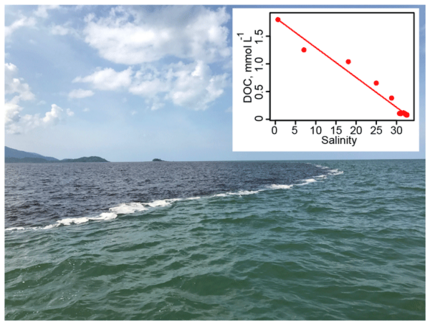

Colored dissolved organic matter (CDOM) is the optically measurable component of dissolved organic matter in water. Also known as chromophoric dissolved organic matter,[1] yellow substance, and gelbstoff, CDOM occurs naturally in aquatic environments and is a complex mixture of many hundreds to thousands of individual, unique organic matter molecules, which are primarily leached from decaying detritus and organic matter.[2] CDOM most strongly absorbs short wavelength light ranging from blue to ultraviolet, whereas pure water absorbs longer wavelength red light. Therefore, water with little or no CDOM, such as the open ocean, appears blue.[3] Waters containing high amounts of CDOM can range from brown, as in many rivers, to yellow and yellow-brown in coastal waters. In general, CDOM concentrations are much higher in fresh waters and estuaries than in the open ocean, though concentrations are highly variable, as is the estimated contribution of CDOM to the total dissolved organic matter pool.

Significance

The concentration of CDOM can have a significant effect on biological activity in aquatic systems. CDOM diminishes light intensity as it penetrates water. Very high concentrations of CDOM can have a limiting effect on photosynthesis and inhibit the growth of phytoplankton,[5][6][7][8] which form the basis of oceanic food chains and are a primary source of atmospheric oxygen. However, the influence of CDOM on algal photosynthesis can be complex in other aquatic systems like lakes where CDOM increases photosynthetic rates at low and moderate concentrations, but decreases photosynthetic rates at high concentrations.[9][7][6][10] CDOM concentrations reflect hierarchical controls.[11] Concentrations vary among lakes in close proximity due to differences in lake and watershed morphometry, and regionally because of difference in climate and dominant vegetation.[12][11][13] CDOM also absorbs harmful UVA/B radiation, protecting organisms from DNA damage.[14]

Absorption of UV radiation causes CDOM to "bleach", reducing its optical density and absorptive capacity. This bleaching (photodegradation) of CDOM produces low-molecular-weight organic compounds which may be utilized by microbes, release nutrients that may be used by phytoplankton as a nutrient source for growth,[15] and generates reactive oxygen species, which may damage tissues and alter the bioavailability of limiting trace metals.

CDOM can be detected and measured from space using satellite remote sensing and often interferes with the use of satellite spectrometers to remotely estimate phytoplankton populations. As a pigment necessary for photosynthesis, chlorophyll is a key indicator of the phytoplankton abundance. However, CDOM and chlorophyll both absorb light in the same spectral range so it is often difficult to differentiate between the two.

Although variations in CDOM are primarily the result of natural processes including changes in the amount and frequency of precipitation, human activities such as logging, agriculture, effluent discharge, and wetland drainage can affect CDOM levels in fresh water and estuarine systems.

Measurement

Traditional methods of measuring CDOM include UV-visible spectroscopy (absorbance) and fluorometry (fluorescence). Optical proxies have been developed to characterize sources and properties of CDOM, including specific ultraviolet absorbance at 254 nm (SUVA254) and spectral slopes for absorbance, and the fluorescence index (FI), biological index (BIX), and humification index (HIX) for fluorescence. Excitation emission matrices (EEMs)[16] can be resolved into components in a technique called parallel factor analysis (PARAFAC),[17] where each component is often labelled as "humic-like", "protein-like", etc. As mentioned above, remote sensing is the newest technique to detect CDOM from space.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ↑ Hoge, FE; Vodacek, A; Swift, RN; Yungel, JK; Blough, NV (October 1995). "Inherent optical properties of the ocean: retrieval of the absorption coefficient of chromophoric dissolved organic matter from airborne laser spectral fluorescence measurements.". Applied Optics 34 (30): 7032–8. doi:10.1364/ao.34.007032. PMID 21060564. Bibcode: 1995ApOpt..34.7032H.,

- ↑ Coble, Paula (2007). "Marine Optical Biogeochemistry: The Chemistry of Ocean Color". Chemical Reviews 107 (2): 402–418. doi:10.1021/cr050350+. PMID 17256912.

- ↑ "Ocean Color". https://science.nasa.gov/earth-science/oceanography/living-ocean/ocean-color.

- ↑ Martin, P., Cherukuru, N., Tan, A.S., Sanwlani, N., Mujahid, A. and Müller, M.(2018) "Distribution and cycling of terrigenous dissolved organic carbon in peatland-draining rivers and coastal waters of Sarawak, Borneo", Biogeosciences, 15(2): 6847–6865. doi:10.5194/bg-15-6847-2018. 50px Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ↑ Stedmon, C.A.; Markager, S.; Kaas, H. (2000). "Optical properties and signatures of chromophoric dissolved organic matter (CDOM) in Danish coastal waters". Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 51 (2): 267–278. doi:10.1006/ecss.2000.0645. Bibcode: 2000ECSS...51..267S.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Seekell, David A.; Lapierre, Jean-François; Ask, Jenny; Bergström, Ann-Kristin; Deininger, Anne; Rodríguez, Patricia; Karlsson, Jan (2015). "The influence of dissolved organic carbon on primary production in northern lakes" (in en). Limnology and Oceanography 60 (4): 1276–1285. doi:10.1002/lno.10096. ISSN 1939-5590. Bibcode: 2015LimOc..60.1276S. https://aslopubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/lno.10096.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Seekell, David A.; Lapierre, Jean-François; Karlsson, Jan (2015-07-14). "Trade-offs between light and nutrient availability across gradients of dissolved organic carbon concentration in Swedish lakes: implications for patterns in primary production" (in en). Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 72 (11): 1663–1671. doi:10.1139/cjfas-2015-0187. https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/abs/10.1139/cjfas-2015-0187.

- ↑ Carpenter, Stephen R.; Cole, Jonathan J.; Kitchell, James F.; Pace, Michael L. (1998). "Impact of dissolved organic carbon, phosphorus, and grazing on phytoplankton biomass and production in experimental lakes" (in en). Limnology and Oceanography 43 (1): 73–80. doi:10.4319/lo.1998.43.1.0073. ISSN 1939-5590.

- ↑ Hansson, Lars-Anders (1992). "Factors regulating periphytic algal biomass" (in en). Limnology and Oceanography 37 (2): 322–328. doi:10.4319/lo.1992.37.2.0322. ISSN 1939-5590. Bibcode: 1992LimOc..37..322H.

- ↑ Kelly, Patrick T.; Solomon, Christopher T.; Zwart, Jacob A.; Jones, Stuart E. (2018-11-01). "A Framework for Understanding Variation in Pelagic Gross Primary Production of Lake Ecosystems" (in en). Ecosystems 21 (7): 1364–1376. doi:10.1007/s10021-018-0226-4. ISSN 1435-0629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-018-0226-4.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Lapierre, Jean-Francois; Collins, Sarah M.; Seekell, David A.; Cheruvelil, Kendra Spence; Tan, Pang-Ning; Skaff, Nicholas K.; Taranu, Zofia E.; Fergus, C. Emi et al. (2018). "Similarity in spatial structure constrains ecosystem relationships: Building a macroscale understanding of lakes" (in en). Global Ecology and Biogeography 27 (10): 1251–1263. doi:10.1111/geb.12781. ISSN 1466-8238.

- ↑ Lapierre, Jean-Francois; Seekell, David A.; Giorgio, Paul A. del (2015). "Climate and landscape influence on indicators of lake carbon cycling through spatial patterns in dissolved organic carbon" (in en). Global Change Biology 21 (12): 4425–4435. doi:10.1111/gcb.13031. ISSN 1365-2486. PMID 26150108. Bibcode: 2015GCBio..21.4425L. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/gcb.13031.

- ↑ Seekell, David A.; Lapierre, Jean-François; Pace, Michael L.; Gudasz, Cristian; Sobek, Sebastian; Tranvik, Lars J. (2014). "Regional-scale variation of dissolved organic carbon concentrations in Swedish lakes" (in en). Limnology and Oceanography 59 (5): 1612–1620. doi:10.4319/lo.2014.59.5.1612. ISSN 1939-5590. Bibcode: 2014LimOc..59.1612S.

- ↑ Sommaruga, Ruben (2001-09-01). "The role of solar UV radiation in the ecology of alpine lakes" (in en). Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology 62 (1–2): 35–42. doi:10.1016/S1011-1344(01)00154-3. ISSN 1011-1344. PMID 11693365. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1011134401001543.

- ↑ Helms, John R.; Stubbins, Aaron; Perdue, E. Michael; Green, Nelson W.; Chen, Hongmei; Mopper, Kenneth (2013). "Photochemical bleaching of oceanic dissolved organic matter and its effect on absorption spectral slope and fluorescence". Marine Chemistry 155: 81–91. doi:10.1016/j.marchem.2013.05.015. Bibcode: 2013MarCh.155...81H.

- ↑ "What is an Excitation Emission Matrix (EEM)?". https://www.horiba.com/en_en/technology/measurement-and-control-techniques/spectroscopy/fluorescence-spectroscopy/what-is-an-excitation-emission-matrix-eem/.

- ↑ Beckmann, Christian. "Parallel Factor Analysis (PARAFAC)". https://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/datasets/techrep/tr04cb1/tr04cb1/node2.html.

External links

- The Color of the Ocean from science@NASA

|