Biology:Common skate

| Common skate | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Superorder: | Batoidea |

| Order: | Rajiformes |

| Family: | Rajidae |

| Genus: | Dipturus |

| Species: | D. batis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Dipturus batis | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The common skate (Dipturus batis), also known as the blue skate, is the largest skate in the world, attaining a length of up to 2.85 m (9 ft 4 in).[2][3][4] Historically, it was one of the most abundant skates in the northeast Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea. Despite its name, today it appears to be absent from much of this range.[5] Where previously abundant, fisheries directly targeted this skate and elsewhere it is caught incidentally as bycatch. The species was uplisted to critically endangered on the IUCN Red List in 2006[1] and it is protected within the EU.[6]

Research published in 2009 and 2010 showed that the species should be split into two, the smaller southern D. cf. flossada (blue skate), and the larger northern D. cf. intermedius (flapper skate).[4][7][8][9] Under this taxonomic arrangement, the name D. batis is discarded.[9][10] Alternatively, the scientific name D. batis (with flossada as a synonym) is retained for the blue skate and D. intermedius for the flapper skate.[11]

Description

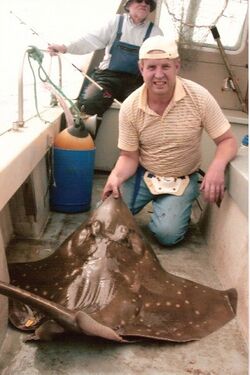

The common skate can reach up to 2.85 m (9 ft 4 in) in length, 2 m (6 ft 7 in) in width, and 113 kg (249 lb) in weight, making it the largest skate in the world.[4][12] Overall shape features a pointed snout and rhombic shape, with a row of spines or thorns along the tail.[13] The top surface is generally coloured olive-grey to brown, often with a pattern of spots, and the underside is lighter blue-grey.[2] It can be confused with several other skates in its range, such as D. nidarosiensis, D. oxyrinchus, and Rostroraja alba.[14]

Range, habitat, and ecology

The common skate is native to the northeast Atlantic.[1] It is a bottom dwelling species mainly found at depths of 100-200m,[2] but it can occur as shallow as 30m[4] and as deep as 1000m.[2] Now, their population and range are severely depleted and fragmented, with disappearances being reported on several places.[1][15] This species is found in northeastern Atlantic from Norway and Iceland to Senegal.[2] Its presence in the Mediterranean Sea is questionable since earlier records could concern D. intermedius recently considered as a distinct species.[16]

Growth and reproduction

The common skate can reach an estimated age of 50–100 years[14] and maturity is reached when about 11 years old.[1] The size where they reach maturity depend on sex and population. In D. cf. flossada (blue skate) males reach maturity when about 1.15 m (3 ft 9 in) long and females when about 1.23 m (4 ft 0 in) long.[17] In D. cf. intermedia (flapper skate), males reach maturity when about 1.86 m (6 ft 1 in) long and females when about 1.98 m (6 ft 6 in) long.[17] The sex ratio is 1:1, but this can vary depending on geography and season. When hatching, juveniles measure up to 22.3 cm (8 3⁄4 in) long.[1] Once they have reached sexual maturity, they reproduce only every other year. They mate in the spring, and during the summer, females lay about 40 egg cases in sandy or muddy flats. The eggs develop for 2–5 months before hatching.[14]

Egg case

Egg cases measure up to 25 cm (10 in) long, excluding the horns, and 15 cm (6 in) wide. They are covered in close-felted fibers and often wash up on the shore.[14]

Egg case hunts have been done throughout the general distribution of the common skate. In the British Isles, egg cases were found only in northern Scotland and the north of Ireland. In the 19th and 20th centuries, egg cases were seen along the entire British coastline in high numbers, but now they are found only in a few areas.[18]

Diet

Like other skates, the common skate is a bottom feeder. Its diet consists of crustaceans, clams, oysters, snails, bristle worms, cephalopods, and small to medium-sized fish (such as sand eel, flatfish, monkfish, catsharks, spurdog, and other skates).[14][19][20] The size of the individual can affect its diet. Larger ones eat larger things like fish.[2] The bigger the skate is, the more food will be needed to sustain its large body size. The activity level determines how much it eats; the more active it is, the more it eats.[21] The common skate does not feed only on creatures at the bottom of the ocean, as some do ascend to feed on mackerel, herring, and other pelagic fish,[22] which are caught by rapidly moving up from the seabed to grab the prey.[14]

Threatened status

The common skate is listed as a critically endangered species by the IUCN and it is threatened both in the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea.[1] The common skate's population has drastically decreased because of overfishing and it likely will disappear entirely unless more is done to preserve it.[15] It has both been targeted directly and caught incidentally as bycatch.[1] Due to the profitability of trawl fishing, bycatch likely will remain a serious problem for the common skate.[1] The species is extirpated in the Baltic Sea.[23] Remaining strongholds where it remains locally common are off western Scotland and in the Celtic Sea.[4][24] A stronghold along the coast of Norway has been suggested,[4] but recent studies indicate the species is rare there and many previous records are the result of misidentifications of other skates.[25][26]

Because the common skate is long-lived and slow to mature, it may be slow to repopulate,[27] but experience with the related barndoor skate (D. laevis) of the northwest Atlantic indicates that a population recovery may be possible in a relatively short time.[28] The common skate is strictly protected within the EU, making it illegal for commercial fishers to actively fish for it or keep it if accidentally landed.[6] Like other elasmobranchs, it is believed to have a good chance of surviving if released after being caught.[14]

Taxonomy

Distinct genetic and morphological differences exist within the common skate as traditionally defined, leading to the recommendation of splitting it into two species: The smaller (up to about 1.45 m or 4.8 ft in length) southern D. cf. flossada (blue skate), and the larger and slower-growing northern D. cf. intermedius (flapper skate).[4][7][8][9][14] Under this taxonomic arrangement, the name D. batis is discarded.[9][10] Alternatively, the scientific name D. batis (with flossada as a synonym) is retained for the blue skate and D. intermedius for the flapper skate.[11] A formal request of preserving the name D. batis (with flossada as a synonym) for the blue skate has been submitted to the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature, but as of 2017 a decision is still pending.[24]

Based on molecular phylogenetics, D. cf. intermedius is very close to D. oxyrinchus, while the relationship to D. cf. flossada is more distant.[4][9][25]

D. cf. intermedius has dark olive-green eyes and the blotch on each wing consists of a group of pale spots.[9][14][17] D. cf. flossada has pale yellow eyes, and the blotch on each wing is relatively large, roughly round, dark and with a pale ring around it.[9][14][17] Additional differences between the two are found in the thorns on their tails and other morphometric features.[9][17] Both are found around the British Isles, and their ranges broadly overlap in the seas around this archipelago, but D. cf. intermedius is the most frequent species in the northern half (off Scotland and Northern Ireland), and D. cf. flossada is the most frequent in the southwest (Celtic Sea) and at Rockall.[4][29] The primary—possibly only—species in Ireland is D. cf. flossada based mainly on the ICES International Bottom Trawl Survey and zoological specimens,[29] the species off Norway is D. cf. intermedius (no confirmed records of D. cf. flossada, but it might occur),[25][26] and based on limited data the main in the North Sea, Skagerrak and Kattegat is D. cf. intermedius (although at least one record of D. cf. flossada in this region, off west Sweden, has been reported).[29][30] Uncertainty exists about the exact species involved in the southern half of the range, but a preliminary morphological study indicates that the one in the Azores is D. cf. intermedius.[31]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Ellis, J.; McCully-Philipps, S.R.; Sims, D.; Derrick, D.; Cheok, J.; Dulvy, N.K. (2021). "Dipturus batis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2021: e.T203364219A203375487. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-2.RLTS.T203364219A203375487.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/203364219/203375487. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2017). "Dipturus batis" in FishBase. January 2017 version.

- ↑ Florida Museum of Natural History. "Ray and Skate: Basic Questions". http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/education/questions/RayBasics.html. Retrieved 2007-10-29.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 Griffiths AM, Sims DW, Cotterell SJ, El Nagar A, Ellis JR, Lynghammar A, McHugh M, Neat FC, Pade NG, Queiroz N, et al. 2010. Molecular markers reveal spatially-segregated cryptic species in a critically endangered fish, the common skate Dipturus batis. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 277: 1497–1503.

- ↑ Brander, K. (1981). "Disappearance of common skate Raja batis from Irish Sea". Nature 290 (5801): 48–49. doi:10.1038/290048a0. Bibcode: 1981Natur.290...48B.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 ICES (11 October 2016)5.3.12 Common skate (Dipturus batis-complex (blue skate (Dipturus batis) and flapper skate (Dipturus cf. intermedia)) in subareas 6–7 (excluding Division 7.d) (Celtic Seas and western English Channel) . ICES Advice 2016, Book 5.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Is 80-Year-Old Mistake Leading to First Species to Be Fished to Extinction?, ScienceDaily 17 November 2009

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Skate may be fished to extinction". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/8367045.stm.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 Iglesias SP, Toulhoat L, Sellos DY. 2009. Taxonomic confusion and market mislabelling of threatened skates: important consequences for their conservation status. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 20: 319–333.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 White W.T. and P.R. Last. 2012. A review of the taxonomy of chondrichthyan fishes: a modern perspective. Journal of Fish Biology 80: 901–917.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Last, P.R.; Weigman, S.; Yang, L. (2016). "Changes to the nomenclature of the skates (Chondrichthyes: Rajiformes)". Rays of the World: Supplementary Information. CSIRO Special Publication. pp. 11–34. ISBN 9781486308019.

- ↑ Muus, B.; J.G. Nielsen; P. Dahlstrom; B. Nystrom (1999). Sea Fish. Scandinavian Fishing Year Book. pp. 68–69. ISBN 8790787005.

- ↑ ARKive. "Common skate – Dipturus batis". http://www.arkive.org/species/GES/fish/Dipturus_batis/. Retrieved 2007-10-29.

- ↑ 14.00 14.01 14.02 14.03 14.04 14.05 14.06 14.07 14.08 14.09 "Common skate : Dipturus batis". http://www.sharktrust.org/shared/downloads/factsheets/common_skate_st_factsheet.pdf. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Background Document for Common skate : Dipturus batis". http://qsr2010.ospar.org/media/assessments/Species/P00477_common_skate.pdf. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- ↑ Guide of Mediterranean Skates and Rays (Dipturus batis). Oct. 2022. Mendez L., Bacquet A. and F. Briand.http://www.ciesm.org/Guide/skatesandrays/questionable-species/

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 ICES (October 2012). European Commission special request on spatial distribution, stock status, and advice on Dipturus species. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ↑ "The Shark Trust – Common/Flapper Skate". http://www.sharktrust.org/en/common_skate_results. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- ↑ "The Benthic Zone: The Sea Floor". 23 December 2009. http://www.brighthub.com/environment/science-environmental/articles/60014.aspx. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ↑ "BIOTIC Species Information for Dipturus batis". http://www.marlin.ac.uk/biotic/browse.php?sp=4257. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ↑ Wearmouth, Victoria J.; Sims, David W. (2009). "Movement and behaviour patterns of the critically endangered common skate Dipturus batis revealed by electronic tagging". Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 380 (1–2): 77–87. doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2009.07.035.

- ↑ "Common Skate". http://www.uk-fish.info/pages/commonskate.html. Retrieved 2017-01-16.

- ↑ HELCOM (2013). "HELCOM Red List of Baltic Sea species in danger of becoming extinct". Baltic Sea Environmental Proceedings (140): 72. http://helcom.fi/Lists/Publications/BSEP140.pdf. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 ICES (2017). WGEF Report. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Lynghammar, A.; J.S. Christiansen; A.M. Griffiths; S.-E. Fevolden; H. Hop; T. Bakken (2014). "DNA barcoding of the northern Northeast Atlantic skates (Chondrichthyes, Rajiformes), with remarks on the widely distributed starry ray". Zoologica Scripta 43 (5): 485–495. doi:10.1111/zsc.12064.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "Dipturus batis (Linnaeus, 1758)" (in Norwegian). Norsk Rødliste [Norwegian Red List]. https://artsdatabanken.no/Rodliste2015/rodliste2015/Norge/42540. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ↑ "Descriptions and articles about the Blue Skate (Dipturus batis) – Encyclopedia of Life". Encyclopedia of Life. http://eol.org/pages/217969/details#threats.

- ↑ Neat; Pinto; Burrett; Cowie; Travis; Thorburn; Gibb; Wright (2014). "Site fidelity, survival and conservation options for the threatened flapper skate (Dipturus cf. intermedia)". Aquatic Conservation 25 (1): 6–20. doi:10.1002/aqc.2472.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 ICES (October 2012). Rays and Skates in the Celtic Sea. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ↑ ICES (9 October 2015). Common skate (Dipturus batis-complex) in Subarea IV and Division IIIa (North Sea, Skagerrak, and Kattegat). Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ↑ Das, D.; P. Afonso (6 November 2017). "Review of the Diversity, Ecology, and Conservation of Elasmobranchs in the Azores Region, Mid-North Atlantic". Front. Mar. Sci. 4: 354: 1–19. doi:10.3389/fmars.2017.00354.

External links

- Photos of Common skate on Sealife Collection

Wikidata ☰ Q1421947 entry