Biology:Common tern

| Common tern | |

|---|---|

| |

| File:Sterna-hirundo-002.ogg | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Laridae |

| Genus: | Sterna |

| Species: | S. hirundo

|

| Binomial name | |

| Sterna hirundo | |

| |

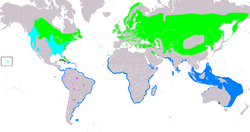

Breeding Resident Non-breeding Passage Vagrant (seasonality uncertain)

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The common tern[2] (Sterna hirundo) is a seabird in the family Laridae. This bird has a circumpolar distribution, its four subspecies breeding in temperate and subarctic regions of Europe, Asia and North America. It is strongly migratory, wintering in coastal tropical and subtropical regions. Breeding adults have light grey upperparts, white to very light grey underparts, a black cap, orange-red legs, and a narrow pointed bill. Depending on the subspecies, the bill may be mostly red with a black tip or all black. There are several similar species, including the partly sympatric Arctic tern, which can be separated on plumage details, leg and bill colour, or vocalisations.

Breeding in a wider range of habitats than any of its relatives, the common tern nests on any flat, poorly vegetated surface close to water, including beaches and islands, and it readily adapts to artificial substrates such as floating rafts. The nest may be a bare scrape in sand or gravel, but it is often lined or edged with whatever debris is available. Up to three eggs may be laid, their dull colours and blotchy patterns providing camouflage on the open beach. Incubation is by both sexes, and the eggs hatch in around 21–22 days, longer if the colony is disturbed by predators. The downy chicks fledge in 22–28 days. Like most terns, this species feeds by plunge-diving for fish, either in the sea or in freshwater, but molluscs, crustaceans and other invertebrate prey may form a significant part of the diet in some areas.

Eggs and young are vulnerable to predation by mammals such as rats and American mink, and large birds including gulls, owls and herons. Common terns may be infected by lice, parasitic worms, and mites, although blood parasites appear to be rare. Its large population and huge breeding range mean that this species is classed as being of least concern, although numbers in North America have declined sharply in recent decades. Despite international legislation protecting the common tern, in some areas, populations are threatened by habitat loss, pollution, or the disturbance of breeding colonies.

Taxonomy

Terns are small to medium-sized seabirds closely related to the gulls, skimmers and skuas. They are gull-like in appearance, but typically have a lighter build, long pointed wings (which give them a fast, buoyant flight), a deeply forked tail, slender legs,[3] and webbed feet.[4] Most species are grey above and white below, and have a black cap which is reduced or flecked with white in the non-breeding season.[3]

The common tern's closest relatives appear to be the Antarctic tern,[5] followed by the Eurasian Arctic and roseate terns. Genetic evidence suggests that the common tern may have diverged from an ancestral stock earlier than its relatives.[6] No fossils are known from North America, and those claimed in Europe are of uncertain age and species.[5]

The common tern was first described by Carl Linnaeus in his landmark 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae under its current scientific name, Sterna hirundo.[7] "Stearn" was used in Old English, and a similar word was used by the Frisians for the birds.[8] "Stearn" appears in the poem The Seafarer, written around 1000 A.D.[8] Linnaeus adopted this word for the genus name Sterna. The Latin for swallow is hirundo, and refers here to the tern's superficial likeness to that unrelated bird, which has a similar light build and long forked tail.[9] This resemblance also leads to the informal name "sea swallow",[10] recorded from at least the seventeenth century.[9] The Scots names picktarnie,[11] tarrock[12] and their many variants are also believed to be onomatopoeic, derived from the distinctive call.[9] Because of the difficulty in distinguishing the two species, all the informal common names are shared with the Arctic tern.[13] The there was some uncertainty whether Sterna hirundo should apply to the common tern or the arctic tern as the species are very similar and both occur in Sweden. In 1913, the Swedish zoologist Einar Lönnberg concluded that the binomial name Sterna hirundo applied to the common tern.[14]

Four subspecies of the common tern are generally recognized, although S. h. minussensis is sometimes considered an intergrade between S. h. hirundo and S. h. longipennis.[15][16]

| Subspecies | Breeding range | Distinctive features |

|---|---|---|

| S. h. hirundo Linnaeus, 1758 |

Europe, North Africa, Asia east to western Siberia and Kazakhstan, and North America.[17] | Differences between the North American and Eurasian populations are minimal. North American birds have a slightly shorter wing length on average, and the extent of the black tip on the upper mandible tends to be less than in birds from Scandinavia and further east in Eurasia. The proportion of black on the bill is at its minimum in the west of Europe, so British breeders are very similar to North American birds in this respect.[17] |

| S. h. minussensis Sushkin, 1925 |

Lake Baikal east to northern Mongolia and southern Tibet.[18] | Paler upper body and wings than S. h. longipennis, black-tipped crimson bill.[18] |

| S. h. longipennis Nordmann, 1835 |

Central Siberia to China, also Alaska.[17] | Darker grey than the nominate subspecies, with shorter black bill, darker red-brown legs, and longer wings.[17] |

| S. h. tibetana Saunders, 1876 |

Himalayas to southern Mongolia and China.[17] | Like the nominate subspecies, but with a shorter bill and a broader black tip.[17] |

Description

The nominate subspecies of the common tern is 31–35 cm (12–14 in) long, including a 6–9 cm (2.4–3.5 in) fork in the tail, with a 77–98 cm (30–39 in) wingspan. It weighs 110–141 g (3.9–5.0 oz).[17] Breeding adults have pale grey upperparts, very pale grey underparts, a black cap, orange-red legs, and a narrow pointed bill that can be mostly red with a black tip, or all black, depending on the subspecies.[19] The common tern's upper wings are pale grey, but as the summer wears on, the dark feather shafts of the outer flight feathers become exposed, and a grey wedge appears on the wings. The rump and tail are white, and on a standing bird the long tail extends no further than the folded wingtips, unlike the Arctic and roseate terns in which the tail protrudes beyond the wings. There are no significant differences between the sexes.[20] In non-breeding adults, the forehead and underparts become white, the bill is all black or black with a red base, and the legs are dark red or black.[20] The upper wings have an obvious dark area at the front edge of the wing, the carpal bar. Terns that have not bred successfully may moult into non-breeding adult plumage beginning in June, though late July is more typical, with the moult suspended during migration. There is also some geographical variation; California n birds are often in non-breeding plumage during migration.[17]

Juvenile common terns have pale grey upper wings with a dark carpal bar. The crown and nape are brown, and the forehead is ginger, wearing to white by autumn. The upper parts are ginger with brown and white scaling, and the tail lacks the adult's long outer feathers.[17] Birds in their first post-juvenile plumage, which normally remain in their wintering areas, resemble the non-breeding adult, but have a duskier crown, dark carpal bar, and often very worn plumage. By their second year, most young terns are either indistinguishable from adults, or show only minor differences such as a darker bill or white forehead.[21]

The common tern is an agile flyer, capable of rapid turns and swoops, hovering, and vertical take-off. When commuting with fish, it flies close to the surface in a strong head wind, but 10–30 m (33–98 ft) above the water in a following wind. Unless migrating, normally it stays below 100 m (330 ft), and averages 30 km/h (19 mph) in the absence of a tail wind.[5] Its average flight speed during the nocturnal migration flight is 43–54 km/h (27–34 mph)[22] at a height of 1,000–3,000 m (3,300–9,800 ft).[5]

Moult

Juveniles moult into adult plumage in its first October; first the head, tail, and body plumage is replaced, mostly by February, then the wing feathers. The primaries are replaced in stages; the innermost feathers moult first, then replacement is suspended during the southern winter (birds of this age staying in their wintering areas) and recommences in the autumn. In May to June of the second year, a similar moult sequence starts, with a pause during primary moult for birds that return north, but not for those that stay in the winter quarters. A major moult to adult breeding plumage occurs in the next February to June, between forty and ninety per cent of feathers being replaced.[17] Old primary feathers wear away to reveal the blackish barbs beneath. The moult pattern means that the oldest feathers are those nearest the middle of the wing, so as the northern summer progresses, a dark wedge appears on the wing because of this feather ageing process.[19]

Terns are unusual in the frequency in which they moult their primaries, which are replaced at least twice, occasionally three times in a year. The visible difference in feather age is accentuated in the greater ultraviolet reflectance of new primaries, and the freshness of the wing feathers is used by females in mate selection.[23] Experienced females favor mates which best show their fitness through the quality of their wing feathers.[24] Rarely, a very early moult at the nesting colony is linked to breeding failure, both the onset of moult and reproductive behaviour being linked to falling levels of the hormone prolactin.[25]

Similar species

There are several terns of a similar size and general appearance to the common tern. A traditionally difficult species to separate is the Arctic tern, and until the key characteristics were clarified, distant or flying birds of the two species were often jointly recorded as "commic terns". Although similar in size, the two terns differ in structure and flight. The common tern has a larger head, thicker neck, longer legs, and more triangular and stiffer wings than its relative, and has a more powerful, direct flight.[26] Arctic terns have greyer underparts than the common variety, which makes its white cheeks more obvious, whereas the rump of the common tern can be greyish in non-breeding plumage, compared to the white of its relative. The common tern develops a dark wedge on the wings as the breeding season progresses, but the wings of the Arctic stay white throughout the northern summer. All the flight feathers of the Arctic tern are translucent against a bright sky, only the four innermost wing feathers of the common tern share this property.[26][27] The trailing edge of the outer flight feathers is a thin black line in the Arctic tern, but thicker and less defined in the common.[20] The bill of an adult common tern is orange-red with a black tip, except in black-billed S. h. longipennis, and its legs are bright red, while both features are a darker red colour in the Arctic tern, which also lacks the black bill tip.[26]

In the breeding areas, the roseate tern can be distinguished by its pale plumage, long, mainly black bill and very long tail feathers.[27] The non-breeding plumage of roseate is pale above and white, sometimes pink-tinged, below. It retains the long tail streamers, and has a black bill.[28] In flight, the roseate's heavier head and neck, long bill and faster, stiffer wingbeats are also characteristic.[29] It feeds further out to sea than the common tern.[28] In North America, the Forster's tern in breeding plumage is obviously larger than the common, with relatively short wings, a heavy head and thick bill, and long, strong legs; in all non-breeding plumages, its white head and dark eye patch make the American species unmistakable.[30]

In the wintering regions, there are also confusion species, including the Antarctic tern of the southern oceans, the South American tern, the Australasian white-fronted tern and the white-cheeked tern of the Indian Ocean. The plumage differences due to "opposite" breeding seasons may aid in identification. The Antarctic tern is more sturdy than the common, with a heavier bill. In breeding condition, its dusky underparts and full black cap outline a white cheek stripe. In non-breeding plumages, it lacks, or has only an indistinct, carpal bar, and young birds show dark bars on the tertials, obvious on the closed wing and in flight.[31][32] The South American tern is larger than the common, with a larger, more curved red bill, and has a smoother, more extensive black cap in non-breeding plumage.[33] Like Antarctic, it lacks a strong carpal bar in non-breeding plumages, and it also shares the distinctive barring of the tertials in young birds.[34] The white-fronted tern has a white forehead in breeding plumage, a heavier bill, and in non-breeding plumage is paler below than the common, with white underwings.[35] The white-cheeked tern is smaller, has uniform grey upperparts, and in breeding plumage is darker above with whiter cheeks.[36]

Juvenile common terns are easily separated from similar-aged birds of related species. They show extensive ginger colouration to the back, and have a pale base to the bill. Young Arctic terns have a grey back and black bill, and juvenile roseate terns have a distinctive scalloped "saddle".[20] Hybrids between common and roseate terns have been recorded, particularly from the US, and the intermediate plumage and calls shown by these birds is a potential identification pitfall. Such birds may have more extensive black on the bill, but confirmation of mixed breeding may depend on the exact details of individual flight feathers.[17]

Voice

Common terns have a wide repertoire of calls, which have a lower pitch than the equivalent calls of Arctic terns. The most distinctive sound is the alarm KEE-yah, stressed on the first syllable, in contrast to the second-syllable stress of the Arctic tern. The alarm call doubles up as a warning to intruders, although serious threats evoke a kyar, given as a tern takes flight, and quietens the usually noisy colony while its residents assess the danger.[37] A down-slurred keeur is given when an adult is approaching the nest while carrying a fish, and is possibly used for individual recognition (chicks emerge from hiding when they hear their parents giving this call). Another common call is a kip uttered during social contact. Other vocalizations include a kakakakaka when attacking intruders, and a staccato kek-kek-kek from fighting males.[37]

Parents and chicks can locate one another by call, and siblings also recognise each other's vocalisations from about the twelfth day from hatching, which helps to keep the brood together.[38][39]

Distribution and habitat

Most populations of the common tern are strongly migratory, wintering south of their temperate and subarctic Northern Hemisphere breeding ranges. First summer birds usually remain in their wintering quarters, although a few return to breeding colonies some time after the arrival of the adults.[21] In North America, the common tern breeds along the Atlantic coast from Labrador to North Carolina, and inland throughout much of Canada east of the Rocky Mountains. In the United States, some breeding populations can also be found in the states bordering the Great Lakes, and locally on the Gulf coast.[40] There are small, only partially migratory, colonies in the Caribbean; these are in The Bahamas and Cuba,[41] and off Venezuela in the Los Roques and Las Aves archipelagos.[42]

New World birds winter along both coasts of Central and South America, to Argentina on the east coast and to northern Chile on the west coast.[21][40] Records from South America and the Azores show that some birds may cross the Atlantic in both directions on their migration.[43][44]

The common tern breeds across most of Europe, with the highest numbers in the north and east of the continent. There are small populations on the north African coast, and in the Azores, Canary Islands and Madeira. Most winter off western or southern Africa, birds from the south and west of Europe tending to stay north of the equator and other European birds moving further south.[45] The breeding range continues across the temperate and taiga zones of Asia, with scattered outposts on the Persian Gulf and the coast of Iran.[46] Small populations breed on islands off Sri Lanka,[47][48] and in the Ladakh region of the Tibetan plateau.[49] Western Asian birds winter in the northern Indian Ocean,[21][50] and S. h. tibetana appears to be common off East Africa during the Northern Hemisphere winter.[51] Birds from further north and east in Asia, such as S. h. longipennis, move through Japan, Thailand and the western Pacific as far as southern Australia.[21] There are small and erratic colonies in West Africa, in Nigeria and Guinea-Bissau, unusual in that they are within what is mainly a wintering area.[46] Only a few common terns have been recorded in New Zealand,[52] and this species' status in Polynesia is unclear.[53] A bird ringed at the nest in Sweden was found dead on Stewart Island, New Zealand, five months later, having flown an estimated 25,000 km (15,000 mi).[54]

As long-distance migrants, common terns sometimes occur well outside their normal range. Stray birds have been found inland in Africa (Zambia and Malawi), and on the Maldives and Comoros islands;[55] the nominate subspecies has reached Australia,[35] the Andes, and the interior of South America.[33][56] Asian S. h. longipennis has recent records from western Europe.[57]

The common tern breeds over a wider range of habitats than any of its relatives, nesting from the taiga of Asia to tropical shores,[58] and at altitudes up to 2,000 m (6,600 ft) in Armenia, and 4,800 m (15,700 ft) in Asia.[45] It avoids areas which are frequently exposed to excessive rain or wind, and also icy waters, so it does not breed as far north as the Arctic tern. The common tern breeds close to freshwater or the sea on almost any open flat habitat, including sand or shingle beaches, firm dune areas, salt marsh, or, most commonly, islands. Flat grassland or heath, or even large flat rocks may be suitable in an island environment.[58] In mixed colonies, common terns will tolerate somewhat longer ground vegetation than Arctic terns, but avoid the even taller growth acceptable to roseate terns; the relevant factor here is the different leg lengths of the three species.[59] Common terns adapt readily to artificial floating rafts, and may even nest on flat factory roofs.[58] Unusual nest sites include hay bales, a stump 0.6 m (2 ft) above the water, and floating logs or vegetation. There is a record of a common tern taking over a spotted sandpiper nest and laying its eggs with those of the wader.[60] Outside the breeding season, all that is needed in terms of habitat is access to fishing areas, and somewhere to land. In addition to natural beaches and rocks, boats, buoys and piers are often used both as perches and as night-time roosts.[58]

Behaviour

Territory

The common tern breeds in colonies which do not normally exceed two thousand pairs,[45] but may occasionally number more than twenty thousand pairs.[61] Colonies inland tend to be smaller than on the coast. Common terns often nest alongside other coastal species, such as Arctic,[62] roseate and Sandwich terns, black-headed gulls,[63][64] and black skimmers.[65] Especially in the early part of the breeding season, for no known reason, most or all of the terns will fly in silence low and fast out to sea. This phenomenon is called a "dread".[45]

On their return to the breeding sites, the terns may loiter for a few days before settling into a territory,[66] and the actual start of nesting may be linked to a high availability of fish.[67] Terns defend only a small area, with distances between nests sometimes being as little as 50 cm (20 in), although 150–350 cm (59–138 in) is more typical. As with many birds, the same site is re-used year after year, with a record of one pair returning for 17 successive breeding seasons. Around ninety per cent of experienced birds reuse their former territory, so young birds must nest on the periphery, find a bereaved mate, or move to another colony.[66] A male selects a nesting territory a few days after his arrival in the spring, and is joined by his previous partner unless she is more than five days late, in which case the pair may separate.[68]

The defence of the territory is mainly by the male, who repels intruders of either sex. He gives an alarm call, opens his wings, raises his tail and bows his head to show the black cap. If the intruder persists, the male stops calling and fights by bill grappling until the intruder submits by raising its head to expose the throat. Aerial trespassers are simply attacked, sometimes following a joint upward spiralling flight.[66] Despite the aggression shown to adults, wandering chicks are usually tolerated, whereas in a gull colony they would be attacked and killed. The nest is defended until the chicks have fledged, and all the adults in the colony will collectively repel potential predators.[69]

Breeding

Pairs are established or confirmed through aerial courtship displays in which a male and a female fly in wide circles up to 200 m (660 ft) or more, calling all the while, before the two birds descend together in zigzag glides. If the male is carrying a fish, he may attract the attention of other males too. On the ground, the male courts the female by circling her with his tail and neck raised, head pointing down, and wings partially open. If she responds, they may both adopt a posture with the head pointed skywards. The male may tease a female with the fish, not parting with his offering until she has displayed to him sufficiently.[70] Once courtship is complete, the male makes a shallow depression in the sand, and the female scratches in the same place. Several trials may take place until the pair settle on a site for the actual nest.[70] The eggs may be laid on bare sand, gravel or soil, but a lining of debris or vegetation is often added if available,[45] or the nest may be rimmed with seaweed, stones or shells. The saucer-shaped scrape is typically 4 cm (1.6 in) deep and 10 cm (3.9 in) across, but may extend to as much as 24 cm (9.4 in) wide including the surrounding decorative material.[71] Breeding success in areas prone to flooding has been enhanced by the provision of artificial mats made from eelgrass, which encourage the terns to nest in higher, less vulnerable areas, since many prefer the mats to bare sand.[72] The common tern tends to use more nest material than roseate or Arctic terns, although roseate often nests in areas with more growing vegetation.[73][74]

Terns are expert at locating their nests in a large colony. Studies show that terns can find and excavate their eggs when they are buried, even if the nest material is removed and the sand smoothed over. They will find a nest placed 5 m (16 ft) from its original site, or even further if it is moved in several stages. Eggs are accepted if reshaped with plasticine or coloured yellow (but not red or blue). This ability to locate the eggs is an adaptation to life in an unstable, wind-blown and tidal environment.[59]

The peak time for egg production is early May, with some birds, particularly first-time breeders, laying later in the month or in June.[60][71] The clutch size is normally three eggs; larger clutches probably result from two females laying in the same nest. Egg size averages 41 mm × 31 mm (1.6 in × 1.2 in), although each successive egg in a clutch is slightly smaller than the first laid.[71] The average egg weight is 20.2 g (0.71 oz), of which five per cent is shell.[75] The egg weight depends on how well-fed the female is, as well as on its position in the clutch. The eggs are cream, buff, or pale brown, marked with streaks, spots or blotches of black, brown or grey which help to camouflage them.[71] Incubation is by both sexes, although more often by the female, and lasts 21–22 days,[75] extending to 25 days if there are frequent disturbances at the colony which cause the adults to leave the eggs unattended;[71] nocturnal predation may lead to incubation taking up to 34 days.[60] On hot days the incubating parent may fly to water to wet its belly feathers before returning to the eggs, thus affording the eggs some cooling.[5] Except when the colony suffers disaster, ninety per cent of the eggs hatch.[76] The precocial downy chick is yellowish with black or brown markings,[71] and like the eggs, is similar to the equivalent stage of the Arctic tern.[77] The chicks fledge in 22–28 days,[75] usually 25–26.[45] Fledged juveniles are fed at the nest for about five days, and then accompany the adults on fishing expeditions. The young birds may receive supplementary feeds from the parents until the end of the breeding season, and beyond. Common terns have been recorded feeding their offspring on migration and in the wintering grounds, at least until the adults move further south in about December.[5][78]

Like many terns, this species is very defensive of its nest and young, and will harass humans, dogs, muskrats and most diurnal birds, but unlike the more aggressive Arctic tern, it rarely hits the intruder, usually swerving off at the last moment. Adults can discriminate between individual humans, attacking familiar people more intensely than strangers.[79] Nocturnal predators do not elicit similar attacks;[80] colonies can be wiped out by rats, and adults desert the colony for up to eight hours when great horned owls are present.[81]

Common terns usually breed once a year. Second clutches are possible if the first is lost. Rarely, a second clutch may be laid and incubated while some chicks from the first clutch are still being fed.[82] The first breeding attempt is usually at four years of age, sometimes at three years. The average number of young per pair surviving to fledging can vary from zero in the event of the colony being flooded to over 2.5 in a good year. In North America, productivity was between 1.0 and 2.0 on islands, but less than 1.0 at coastal and inland sites. Birds become more successful at raising chicks with age. This continues throughout their breeding lives, but the biggest increase is in the first five years.[5][77] The maximum documented lifespan in the wild is 23 years in North America[83][84] and 33 years in Europe,[85][86] but twelve years is a more typical lifespan.[75]

-

Nest site, Elliston, Newfoundland and Labrador

-

Nest in the Ebro Delta, Tarragona, Catalonia, Spain

-

Egg, Collection Museum Wiesbaden

-

Three eggs in a nest on Great Gull Island

-

A chick on an island off the coast of Maine

-

Hovering and screaming to deter intruders on Great Gull Island

-

This autumn juvenile in Massachusetts has a white forehead, having lost the ginger colouration characteristic of younger birds.

Food and feeding

Like all Sterna terns, the common tern feeds by plunge-diving for fish, from a height of 1–6 m (3.3–19.7 ft), either in the sea or in freshwater lakes and large rivers. The bird may submerge for a second or so, but to no more than 50 cm (20 in) below the surface.[87] When seeking fish, this tern flies head-down and with its bill held vertically.[59] It may circle or hover before diving, and then plunges directly into the water, whereas the Arctic tern favours a "stepped-hover" technique,[88] and the roseate tern dives at speed from a greater height, and submerges for longer.[89] The common tern typically forages up to 5–10 km (3.1–6.2 mi) away from the breeding colony, sometimes as far as 15 km (9.3 mi).[90] It will follow schools of fish, and its west African migration route is affected by the location of huge shoals of sardines off the coast of Ghana;[87] it will also track groups of predatory fish or dolphins, waiting for their prey to be driven to the sea's surface.[90][91] Terns often feed in flocks, especially if food is plentiful, and the fishing success rate in a flock is typically about one-third higher than for individuals.[87]

Terns have red oil droplets in the cone cells of the retinas of their eyes. This improves contrast and sharpens distance vision, especially in hazy conditions.[92] Birds that have to see through an air/water interface, such as terns and gulls, have more strongly coloured carotenoid pigments in the cone oil drops than other avian species.[93] The improved eyesight helps terns to locate shoals of fish, although it is uncertain whether they are sighting the phytoplankton on which the fish feed, or observing other terns diving for food.[94] Tern's eyes are not particularly ultraviolet sensitive, an adaptation more suited to terrestrial feeders like the gulls.[95]

The common tern preferentially hunts fish 5–15 cm (2.0–5.9 in) long.[60][87] The species caught depend on what is available, but if there is a choice, terns feeding several chicks will take larger prey than those with smaller broods.[96] The proportion of fish fed to chicks may be as high as ninety-five per cent in some areas, but invertebrate prey may form a significant part of the diet elsewhere. This may include worms, leeches, molluscs such as small squid, and crustaceans (prawns, shrimp and mole crabs). In freshwater areas, large insects may be caught, such as beetles, cockchafers and moths. Adult insects may be caught in the air, and larvae picked from the ground or from the water surface. Prey is caught in the bill and either swallowed head-first, or carried back to the chicks. Occasionally, two or more small fish may be carried simultaneously.[87] When adults take food back to the nest, they recognise their young by call, rather than visual identification.[39]

The common tern may attempt to steal fish from Arctic terns,[97] but might itself be harassed by kleptoparasitic skuas,[98] laughing gulls,[99] roseate terns,[100] or by other common terns while bringing fish back to its nest.[97] In one study, two males whose mates had died spent much time stealing food from neighbouring broods.[101]

Terns normally drink in flight, usually taking seawater in preference to freshwater, if both are available.[5] Chicks do not drink before fledging, reabsorbing water, and, like adults, excreting excess salt in a concentrated solution from a specialised nasal gland.[102][103] Fish bones and the hard exoskeletons of crustaceans or insects are regurgitated as pellets. Adults fly off the nest to defecate, and even small chicks walk a short distance from the scrape to deposit their faeces. Adults attacking animals or humans will often defecate as they dive, often successfully fouling the intruder.[5]

Predators and parasites

Rats will take tern eggs, and may even store large numbers in caches,[104] and the American mink is an important predator of hatched chicks, both in North America, and in Scotland where it has been introduced.[76] The red fox can also be a local problem.[105] Because common terns nest on islands, the most common predators are normally other birds rather than mammals. The ruddy turnstone will take eggs from unattended nests,[106][107] and gulls may take chicks.[108][109] Great horned owls and short-eared owls will kill both adults and chicks, and black-crowned night herons will also eat small chicks.[5][110] Merlins and peregrine falcons may attack flying terns; as with other birds, it seems likely that one advantage of flocking behaviour is to confuse fast-flying predators.[69]

The common tern hosts feather lice, which are quite different from those found in Arctic terns, despite the close relationship of the two birds.[111] It may also be infected by parasitic worms, such as the widespread Diphyllobothrium species, the duck parasite Ligula intestinalis, and Schistocephalus species carried initially by fish. Tapeworms of the family Cyclophyllidea may also infect this species. The mite Reighardia sternae has been found in common terns from Italy, North America and China.[112] A study of 75 breeding common terns found that none carried blood parasites.[113] Colonies have been affected by avian cholera and ornithosis,[5] and it is possible that the common tern may be threatened in the future by outbreaks of avian influenza to which it is susceptible.[90] In 1961 the common tern was the first wild bird species identified as infected with avian influenza, the H5N3 variant being found in an outbreak of South African birds.[114]

Status

The common tern is classed as least concern on the IUCN Red List.[1] It has a large population of 1.6 to 3.3 million mature individuals and a huge breeding range estimated at 84,300,000 km2 (32,500,000 sq mi). Breeding numbers have been estimated at a quarter to half a million pairs, the majority breeding in Asia. About 140 thousand pairs breed in Europe.[115] Fewer than eighty thousand pairs breed in North America, with most breeding on the northeast Atlantic coast[116] and a declining population of less than ten thousand pairs breeding in the Great Lakes region.[117]

In the nineteenth century, the use of tern feathers and wings in the millinery trade was the main cause of large reductions in common tern populations in both Europe and North America, especially on the Atlantic coasts and inland. Sometimes entire stuffed birds were used to make hats. Numbers largely recovered early in the twentieth century mainly due to legislation and the work of conservation organizations.[5][105] Although some Eurasian populations are stable, numbers in North America have fallen by more than seventy per cent in the last forty years, and there is an overall negative trend in the global estimates for this species.[90]

Threats come from habitat loss through building, pollution or vegetation growth, or disturbance of breeding birds by humans, vehicles, boats or dogs. Local natural flooding may lead to nest losses, and some colonies are vulnerable to predation by rats and large gulls. Gulls also compete with terns for nest sites. Some birds are hunted in the Caribbean for commercial sale as food.[90] Breeding success may be enhanced by the use of floating nest rafts, manmade islands or other artificial nest sites, and by preventing human disturbance. Overgrown vegetation may be burned to clear the ground, and gulls can be killed or discouraged by deliberate disturbance.[90] Contamination with polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) resulted in enhanced levels of feminisation in male embryos, which seemed to disappear prior to fledging, with no effect on colony productivity,[118] but dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE), which results from the breakdown of DDT, led to very low levels of successful breeding in some US locations.[5]

The common tern is one of the species to which the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) and the US–Canada Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 apply.[119][120] Parties to the AEWA agreement are required to engage in a wide range of conservation strategies described in a detailed action plan. The plan is intended to address key issues such as species and habitat conservation, management of human activities, research, education, and implementation.[121] The North American legislation is similar, although there is a greater emphasis on protection.[122]

See also

- Lake Bant tern colony

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 BirdLife International (2019). "Sterna hirundo". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: e.T22694623A155537726. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T22694623A155537726.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/22694623/155537726. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ Gill, F; Donsker D, eds. "IOC World Bird Names (v 2.11)". International Ornithologists' Union. http://www.worldbirdnames.org/n-shorebirds.html.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Snow & Perrin (1998) p. 764.

- ↑ Wassink & Ort (1995) p. 78.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 Nisbet, Ian C. "Common Tern (Sterna hirundo)". Cornell Lab of Ornithology. http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/618/articles/introduction.

- ↑ Bridge, Eli S; Jones, Andrew W; Baker, Allan J (2005). "A phylogenetic framework for the terns (Sternini) inferred from mtDNA sequences: implications for taxonomy and plumage evolution". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 35 (2): 459–469. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2004.12.010. PMID 15804415. http://scholar.library.csi.cuny.edu/~fburbrink/Courses/Vertebrate%20systematics%20seminar/Bridge%20et%20al%202005%20.pdf.

- ↑ Linnaeus, Carolus (1758) (in la). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata.. Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii). p. 137.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Sterna (3rd ed.), Oxford University Press, September 2005, http://oed.com/search?searchType=dictionary&q=Sterna (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) Library subscription required.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Hume (1993) pp. 12–13.

- ↑ "Common tern". Birdguide. Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB). http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/speciesfactsheet.php?id=3270.

- ↑ SND: Pictarnie

- ↑ SND: tarrock

- ↑ Cocker & Mabey (2005) pp. 246–247.

- ↑ Lönnberg, Einar (1913). "On Sterna hirundo Linn. and on the name of the Common Tern". Ibis 1 (2): 301–303. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1913.tb06553.x. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/26514527. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ↑ Hume (1993) pp. 88–89.

- ↑ "Sterna hirundo Linnaeus (1758)". Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS). https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=176888.

- ↑ 17.00 17.01 17.02 17.03 17.04 17.05 17.06 17.07 17.08 17.09 17.10 Olsen & Larsson (1995) pp. 77–89.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Brazil (2008) p. 220.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Hume (1993) pp. 21–29.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Vinicombe et al. (1990) pp. 133–138.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 Harrison (1998) pp. 370–374.

- ↑ Alerstam, T (1985). "Strategies of migratory flight, illustrated by Arctic and common terns, Sterna paradisaea and Sterna hirundo". Contributions to Marine Science 27 (supplement on migration: mechanisms and adaptive significance): 580–603.

- ↑ Bridge, Eli S; Eaton, Muir D (2005). "Does ultraviolet reflectance accentuate a sexually selected signal in terns?". Journal of Avian Biology 36 (1): 18–21. doi:10.1111/j.0908-8857.2005.03470.x.

- ↑ Bridge, Eli S; Nisbet, Ian C T (2004). "Wing molt and assortative mating in Common Terns: a test of the molt-signaling hypothesis". Condor 106 (2): 336–343. doi:10.1650/7381.

- ↑ Braasch, Alexander; Garciá, Germán O (2012). "A case of aberrant post-breeding moult coinciding with nest desertion in a female Common Tern". British Birds 105: 154–159.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Hume, Rob A (1993). "Common, Arctic and Roseate Terns: an identification review". British Birds 86: 210–217.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 van Duivendijk (2011) pp. 200–202.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Olsen & Larsson (1995) pp. 69–76.

- ↑ Blomdahl et al. (2007) p. 340.

- ↑ Olsen & Larrson (1995) pp. 103–110.

- ↑ Enticott & Tipling (2002) p. 196.

- ↑ Sinclair et al. (2002) p. 212.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Schulenberg et al. (2010) p. 154.

- ↑ Enticott & Tipling (2002) p. 192.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Simpson & Day (2010) p. 110.

- ↑ Grimmett et al. (1999) pp. 140–141.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Hume (1993) pp. 68–75.

- ↑ Burger, Joanna; Gochfeld, Michael; Boarman, William I (1988). "Experimental evidence for sibling recognition in Common Terns (Sterna hirundo)". Auk 105 (1): 142–148. doi:10.1093/auk/105.1.142. http://sora.unm.edu/node/24524. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Stevenson, J G; Hutchison, R E; Hutchison, J B; Bertram B C R; Thorpe, W H (1970). "Individual recognition by auditory cues in the Common Tern (Sterna hirundo)". Nature 226 (5245): 562–563. doi:10.1038/226562a0. PMID 16057385. Bibcode: 1970Natur.226..562S.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Cuthbert (2003) p. 4.

- ↑ Raffaele et al. (2003) p. 292.

- ↑ Hilty (2002) p. 310.

- ↑ Lima (2006) p. 132.

- ↑ Neves, Verónica C; Bremer, R Esteban; Hays, Helen W (2002). "Recovery in Punta Rasa, Argentina of Common Terns banded in the Azores archipelago, North Atlantic". Waterbirds 25 (4): 459–461. doi:10.1675/1524-4695(2002)025[0459:RIPRAO2.0.CO;2]. http://www.horta.uac.pt/intradop/images/stories/perspages/veronicaneves/09_Waterbirds2002.pdf. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 45.4 45.5 Snow & Perrin (1998) pp. 779–782.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Hume (1993) pp. 39–41.

- ↑ Hoffmann, Thilo W (1990). "Breeding of the Common Tern Sterna hirundo in Sri Lanka". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 87 (1): 68–72. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/48806758. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ↑ Hoffmann, Thilo W (1992). "Confirmation of the breeding of the Common Tern Sterna hirundo Linn. in Sri Lanka". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 89 (2): 251–252. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/48732715. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ↑ Rasmussen & Anderton (2005) pp. 194–195.

- ↑ Khan, Asif N. (1 April 2015). "Record of Common Tern Sterna hirundo from Andaman & Nicobar Islands, India". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society 112 (1): 30. doi:10.17087/jbnhs/2015/v112i1/92329.

- ↑ Zimmerman et al. (2010) p. 354.

- ↑ Robertson & Heather (2005) p. 126.

- ↑ Watling (2003) pp. 204–205.

- ↑ Newton (2010) pp. 150–151.

- ↑ "BirdLife International Species factsheet: Sterna hirundo, additional information". BirdLife International. http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/speciesfactsheet.php?id=3270&m=1.

- ↑ DiCostanzo, Joseph (1978). "Occurrences of the Common Tern in the interior of South America". Bird-Banding 49 (3): 248–251. doi:10.2307/4512366.

- ↑ Darby, Chris (2011). "Eastern Common Terns in Suffolk and Belgium". Birding World 24 (12): 511–512.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 58.3 Hume (1993) pp. 30–37.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 Fisher & Lockley (1989) pp. 252–260.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 60.3 Sandilands (2005) pp. 157–160.

- ↑ de Wolf, P. "BioIndicators and the Quality of the Wadden Sea" in Best & Haeck (1984) p. 362.

- ↑ Robinson, James A; Chivers, Lorraine S; Hamer, Keith C (2001). "A comparison of Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea and Common Tern S. hirundo nest-site characteristics on Coquet Island, north-east England". Atlantic Seabirds 3 (2): 49–58. http://www.seabirdgroup.org.uk/journals/as_3_2.pdf.

- ↑ Ramos, Jaime A; Adrian J (1995). "Nest-site selection by Roseate Terns and Common Terns in the Azores". Auk 112 (3): 580–589. http://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/auk/v112n03/p0580-p0589.pdf. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ Fuchs, Eduard (1977). "Predation and anti-predator behaviour in a mixed colony of terns Sterna sp. and Black-Headed Gulls Larus ridibundus with special reference to the Sandwich Tern Sterna sandvicensis". Ornis Scandinavica 8 (1): 17–32. doi:10.2307/3675984.

- ↑ Erwin, Michael R (1977). "Black Skimmer breeding ecology and behavior". Auk 94 (4): 709–717. doi:10.2307/4085267. http://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/auk/v094n04/p0709-p0717.pdf. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 Hume (1993) pp. 86–90.

- ↑ Safina, Carl; Burger, Joanna (1988). "Prey dynamics and the breeding phenology of Common Terns (Sterna hirundo)". Auk 105 (4): 720–726. doi:10.1093/auk/105.4.720. http://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/auk/v105n04/p0720-p0726.pdf. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ Gonzalez-Solis, J; Becker, P H; Wendeln, H (1999). "Divorce and asynchronous arrival in Common Terns (Sterna hirundo)". Animal Behaviour 58 (5): 1123–1129. doi:10.1006/anbe.1999.1235. PMID 10564616.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Hume (1993) pp. 79–85.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Hume (1993) pp. 91–99.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 71.2 71.3 71.4 71.5 Hume (1993) pp. 100–111.

- ↑ Palestis, Brian G (2009). "Use of artificial eelgrass mats by saltmarsh-nesting Common Terns (Sterna hirundo)". In Vivo 30 (3): 11–16. http://aquaticcommons.org/4729/1/eelgrass_mats.pdf. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ↑ Lloyd et al. (2010) p. 207.

- ↑ Bent (1921) p. 252.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 75.3 "Common Tern Sterna hirundo (Linnaeus, 1758)". BirdFacts. British Trust for Ornithology (BTO). 16 July 2010. http://blx1.bto.org/birdfacts/results/bob6150.htm.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Hume (1993) pp. 112–119.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Hume & Pearson (1993) pp. 121–124.

- ↑ Hume (1993) pp. 120–123.

- ↑ Burger, Joanna; Shealer, D A; Gochfeld, Michael (1993). "Defensive aggression in terns: discrimination and response to individual researchers". Aggressive Behavior 19 (4): 303–311. doi:10.1002/1098-2337(1993)19:4<303::AID-AB2480190406>3.0.CO;2-P.

- ↑ Hunter, Rodger A; Morris, Ralph D (1976). "Nocturnal predation by a Black-Crowned Night Heron at a Common Tern colony". Auk 93 (3): 629–633. http://sora.unm.edu/node/22862. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ Nisbet, Ian C T; Welton, M (1984). "Seasonal variations in breeding success of Common Terns: consequences of predation". Condor 86 (1): 53–60. doi:10.2307/1367345. http://sora.unm.edu/node/103417. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ Hays, H (1984). "Common Terns raise young from successive broods". Auk 101 (2): 274–280. doi:10.1093/auk/101.2.274. http://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/auk/v101n02/p0274-p0280.pdf. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ Nisbet, Ian C T; Cam, Emmanuelle (2002). "Test for age-specificity in survival of the Common Tern". Journal of Applied Statistics 29 (1–4): 65–83. doi:10.1080/02664760120108467. Bibcode: 2002JApSt..29...65N.

- ↑ Austin, Oliver L Sr (1953). "A Common Tern at least 23 years old". Bird-Banding 24 (1): 20. http://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/jfo/v024n01/p0020-p0020.pdf. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ "Longevity records for Britain & Ireland in 2010". Online ringing report. British Trust for Ornithology (BTO). http://blx1.bto.org/ring/countyrec/results2010/longevity.htm.

- ↑ "European Longevity Records". Longevity. Euring. http://www.euring.org/data_and_codes/longevity-voous.htm.

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 87.2 87.3 87.4 Hume (1993) pp. 55–67.

- ↑ Beaman et al. (1998) p. 440.

- ↑ Kirkham, Ian R; Nisbet, Ian C T (1987). "Feeding techniques and field identification of Arctic, Common and Roseate Terns". British Birds 80 (2): 41–47.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 90.2 90.3 90.4 90.5 "BirdLife International Species factsheet: Sterna hirundo". BirdLife International. http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/speciesfactsheet.php?id=3270.

- ↑ Bugoni, Leandro; Vooren, Carolus Maria (2004). "Feeding ecology of the Common Tern Sterna hirundo in a wintering area in southern Brazil". Ibis 146 (3): 438–453. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.2004.00277.x.

- ↑ Sinclair (1985) pp. 93–95.

- ↑ Varela, F J; Palacios, A G; Goldsmith T M (1993) "Vision, Brain, and Behavior in Birds" in Zeigler & Bischof (1993) pp. 77–94.

- ↑ Lythgoe (1979) pp. 180–183.

- ↑ Håstad, Olle; Ernstdotter, Emma; Ödeen, Anders (2005). "Ultraviolet vision and foraging in dip and plunge diving birds". Biology Letters 1 (3): 306–309. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0320. PMID 17148194.

- ↑ Stephens et al. (2007) p. 295.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 Hopkins, C D; Wiley, R H (1972). "Food parasitism and competition in two terns". Auk 89: 583–594. http://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/auk/v089n03/p0583-p0594.pdf. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ Bélisle, M (1998). "Foraging group size: models and a test with jaegers kleptoparasitizing terns". Ecology 79 (6): 1922–1938. doi:10.2307/176699. Bibcode: 1998Ecol...79.1922B. http://spectrum.library.concordia.ca/6255/1/MM18374.pdf. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- ↑ Hatch, J J (1975). "Piracy by laughing gulls Larus atricilla: an example of the selfish group". Ibis 117 (3): 357–365. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1975.tb04222.x.

- ↑ Dunn, E K (1973). "Robbing behavior of Roseate Terns". Auk 90 (3): 641–651. doi:10.2307/4084163. http://sora.unm.edu/node/22405. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ Nisbet, Ian C T; Wilson, Karen J; Broad, William A (1978). "Common Terns raise young after death of their mates". The Condor 80 (1): 106–109. doi:10.2307/1367802. http://sora.unm.edu/node/102828. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ Hughes, M R (1968). "Renal and extrarenal sodium excretion in the Common Tern Sterna hirundo". Physiological Zoology 41 (2): 210–219. doi:10.1086/physzool.41.2.30155452.

- ↑ Karleskint (2009) p. 317.

- ↑ Austin, O L (1948). "Predation by the common rat (Rattus norvegicus) in the Cape Cod colonies of nesting terns". Bird-Banding 19 (2): 60–65. doi:10.2307/4510014.

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 "Common Tern Sterna hirundo". Latest population trends. Joint Nature Conservation Committee, (JNCC). http://jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-2895.

- ↑ Parkes, K C; Poole, A; Lapham, H (1971). "The Ruddy Turnstone as an egg predator". Wilson Bulletin 83: 306–307. http://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/wilson/v083n03/p0306-p0308.pdf. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ Farraway, A; Thomas, K; Blokpoel, H (1986). "Common Tern egg predation by Ruddy Turnstones". Condor 88 (4): 521–522. doi:10.2307/1368282. http://sora.unm.edu/node/103749. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ Houde, P (1977). "Gull-tern interactions on Hicks Island". Proceedings of the Linnaean Society of New York 73: 58–64.

- ↑ Whittam, R M; Leonard, M L (2000). "Characteristics of predators and offspring influence on nest defense by Arctic and Common Terns". Condor 102 (2): 301–306. doi:10.1650/0010-5422(2000)102[0301:COPAOI2.0.CO;2]. http://sora.unm.edu/node/105635. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ Morris, R D; Wiggins, D A (1986). "Ruddy Turnstones, Great Horned Owls, and egg loss from Common Tern clutches". Wilson Bulletin 98: 101–109. http://sora.unm.edu/sites/default/files/journals/wilson/v098n01/p0101-p0109.pdf. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ↑ Rothschild & Clay (1953 ) p. 135.

- ↑ Rothschild & Clay (1953) pp. 194–197.

- ↑ Fiorello, Christine V; Nisbet, Ian C T; Hatch, Jeremy J; Corsiglia, Carolyn; Pokras, Mark A (2009). "Hematology and absence of hemoparasites in breeding Common Terns (Sterna hirundo) from Cape Cod, Massachusetts". Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 40 (3): 409–413. doi:10.1638/2006-0067.1. PMID 19746853.

- ↑ Olsen, Björn; Munster, Vincent J; Wallensten, Anders; Waldenström, Jonas; Osterhaus, D M E; Fouchier, Ron A M (2006). "Global patterns of influenza A virus in wild birds". Science 312 (5772): 384–388. doi:10.1126/science.1122438. PMID 16627734. Bibcode: 2006Sci...312..384O.

- ↑ Enticott (2002) p. 194.

- ↑ Kress, Stephen W; Weinstein, Evelyn H; Nisbet, Ian C T; Shugart, Gary W; Scharf, William C; Blokpoel, Hans; Smith, Gerald A; Karwowski, Kenneth et al. (1983). "The status of tern populations in northeastern United States and adjacent Canada". Colonial Waterbirds 6: 84–106. doi:10.2307/1520976.

- ↑ Cuthbert (2003) p. 1.

- ↑ Hart, Constance A; Nisbet, Ian C T; Kennedy, Sean W; Hahn, Mark E (2003). "Gonadal feminization and halogenated environmental contaminants in Common Terns (Sterna hirundo): evidence that ovotestes in male embryos do not persist to the prefledgling stage". Ecotoxicology 12 (1–4): 125–140. doi:10.1023/A:1022505424074. PMID 12739862. http://www.whoi.edu/science/B/people/mhahn/Hart_Ecotox_proofs.pdf. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ↑ "Annex 2: Waterbird species to which the Agreement applies". Agreement on the conservation of African-Eurasian migratory Waterbirds (AEWA). UNEP/ AEWA Secretariat. http://www.unep-aewa.org/documents/agreement_text/eng/pdf/aewa_agreement_text_annex2.pdf.

- ↑ "List of Migratory Birds". Birds protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. US Fish and Wildlife Service. http://www.fws.gov/migratorybirds/RegulationsPolicies/mbta/mbtandx.html.

- ↑ "Introduction". African-Eurasian Waterbird Agreement. UNEP/ AEWA Secretariat. http://www.unep-aewa.org/about/introduction.htm.

- ↑ "Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918". Digest of Federal Resource Laws of Interest to the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service. http://www.fws.gov/laws/lawsdigest/migtrea.html.

Cited texts

- Beaman, Mark; Madge, Steve; Burn, Hilary; Zetterstrom, Dan (1998). The Handbook of Bird Identification: For Europe and the Western Palearctic. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 0-7136-3960-1.

- Bent, Arthur Cleveland (1921). Life Histories of North American Gulls and Terns: Order Longipennes. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. https://archive.org/details/cu31924022523868.

- Best, E P H; Haeck, J (1984). Ecological Indicators for the Assessment of the Quality of Air, Water, Soil and Ecosystems: Symposium Papers ("Environmental Monitoring & Assessment"). Dordrecht: D Reidel. ISBN 90-277-1708-7.

- Blomdahl, Anders; Breife, Bertil; Holmstrom, Niklas (2007). Flight Identification of European Seabirds. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 978-0-7136-8616-6.

- Brazil, Mark (2008). Birds of East Asia. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 978-0-7136-7040-0.

- Cocker, Mark; Mabey, Richard (2005). Birds Britannica. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0-7011-6907-9.

- Cuthbert, Francesca J; Wires, Linda R; Timmerman, Kristina (2003). Status Assessment and Conservation Recommendations for the Common Tern (Sterna hirundo) in the Great Lakes Region. U S Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Fort Snelling, Minnesota. http://www.fws.gov/midwest/eco_serv/soc/birds/pdf/cote-sa03.pdf.

- van Duivendijk, Nils (2011). Advanced Bird ID Handbook: The Western Palearctic. London: New Holland. ISBN 978-1-78009-022-1.

- Enticott, Jim; Tipling, David (2002). Seabirds of the World. London: New Holland Publishers. ISBN 1-84330-327-2.

- Fisher, James; Lockley, R M (1989). Sea‑Birds (Collins New Naturalist series). London: Bloomsbury Books. ISBN 1-870630-88-2.

- Grimmett, Richard; Inskipp, Carol; Inskipp, Tim (2002). Pocket Guide to Birds of the Indian Subcontinent. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 0-7136-6304-9.

- Harrison, Peter (1988). Seabirds. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 0-7470-1410-8.

- Hilty, Steven L (2002). Birds of Venezuela. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 0-7136-6418-5.

- Hume, Rob (1993). The Common Tern. London: Hamlyn. ISBN 0-540-01266-1.

- Hume, Rob; Pearson, Bruce (1993). Seabirds. London: Hamlyn. ISBN 0-600-57951-4.

- Karleskint, George; Turner, Richard; Small, James (2009). Introduction to Marine Biology. Florence, Kentucky: Brooks/Cole. ISBN 978-0-495-56197-2.

- Lima, Pedro (2006) (in pt, en). Aves do litoral norte da Bahia. Bahia: Atualidades Ornitológicas. http://www.ao.com.br/download/lnbahia.pdf. Retrieved 2012-02-17.

- Linnaeus, C (1758) (in la). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata. Stockholm: Laurentii Salvii.

- Lloyd, Clare; Tasker, Mark L; Partridge, Ken (2010). The Status of Seabirds in Britain and Ireland. London: Poyser. ISBN 978-1-4081-3800-7.

- Lythgoe, J N (1979). The Ecology of Vision. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-854529-0.

- Newton, Ian (2010). Bird Migration. London: Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-730731-9.

- Olsen, Klaus Malling; Larsson, Hans (1995). Terns of Europe and North America. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 0-7136-4056-1.

- Raffaele, Herbert A; Raffaele, Janis I; Wiley, James; Garrido, Orlando H; Keith, Allan R (2003). Field Guide to the Birds of the West Indies. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 0-7136-5419-8.

- Rasmussen, Pamela C; Anderton, John C (2005). Birds of South Asia. The Ripley Guide. Volume 2. Washington DC and Barcelona: Smithsonian Institution and Lynx Edicions. ISBN 84-87334-67-9.

- Robertson, Hugh; Heather, Barrie (2005). The Field Guide to the Birds of New Zealand. Auckland: Penguin Group (NZ). ISBN 0-14-302040-4.

- Rothschild, Miriam; Clay, Theresa (1953). Fleas, Flukes and Cuckoos. A Study of Bird Parasites. London: Collins.

- Sandilands, Allan P (2005). Birds of Ontario: Habitat Requirements, Limiting Factors, and Status Nonpasserines, Waterfowl Through Cranes: 1. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 0-7748-1066-1.

- Schulenberg, Thomas S; Stotz, Douglas F; Lane, Daniel F; O'Neill, John P; Parker, Theodore A (2010). Birds of Peru. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13023-1.

- Simpson, Ken; Day, Nicolas (2010). Field Guide to the Birds of Australia (8th ed.). Camberwell, Victoria: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-670-07231-6.

- Sinclair, Ian; Hockey, Phil; Tarboton, Warwick (2002). SASOL Birds of Southern Africa. Cape Town: Struik. ISBN 1-86872-721-1.

- Sinclair, Sandra (1985). How Animals See: Other Visions of Our World. Beckenham, Kent: Croom Helm. ISBN 0-7099-3336-3.

- Snow, David; Perrins, Christopher M, eds (1998). The Birds of the Western Palearctic (BWP) ((2 volume) Concise ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854099-X.

- Stephens, David W; Brown, Joel Steven; Ydenberg, Ronald C (2007). Foraging: Behavior and Ecology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-77264-6.

- Vinicombe, Keith; Tucker, Laurel; Harris, Alan (1990). The Macmillan Field Guide to Bird Identification. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-42773-4.

- Wassink, Jan L; Ort, Kathleen (1995). Birds of the Pacific Northwest Mountains: The Cascade Range, the Olympic Mountains, Vancouver Island, and the Coast Mountains. Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press. ISBN 0-87842-308-7.

- Watling, Dick (2003). A Guide to the Birds of Fiji and Western Polynesia. Suva, Fiji: Environmental Consultants. ISBN 982-9030-04-0.

- Zeigler, Harris Philip; Bischof, Hans-Joachim (1993). Vision, Brain, and Behavior in Birds: A Comparative Review. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-24036-X.

- Zimmerman, Dale A; Pearson, David J; Turner, Donald A (2010). Birds of Kenya and Northern Tanzania. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 978-0-7136-7550-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to the common tern. |

- Common tern – Species text in The Atlas of Southern African Birds

- "Common tern media". Internet Bird Collection. http://www.hbw.com/ibc/species/common-tern-sterna-hirundo.

- Common Tern Species Account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Common tern – Sterna hirundo – USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Common Tern Profile – Madeira Wind Birds

- Common tern photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

Wikidata ☰ Q18875 entry

|