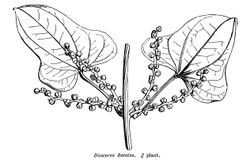

Biology:Dioscoreales

| Dioscoreales | |

|---|---|

| |

| Dioscorea communis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Order: | Dioscoreales Mart.[1][2][3] |

| Type species | |

| Dioscorea villosa | |

| Families | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The Dioscoreales are an order of monocotyledonous flowering plants, organized under modern classification systems, such as the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group or the Angiosperm Phylogeny Web. Among monocot plants, Dioscoreales are grouped with the lilioid monocots, wherein they are a sister group to the Pandanales. In total, the order Dioscoreales comprises three families, 22 genera and about 850 species.

Dioscoreales contains the family Dioscoreaceae, which notably includes the yams (Dioscorea) and several other bulbous and tuberous plants, some of which are heavily cultivated as staple food sources in certain countries.

Certain species are found solely in arid climates (incl. parts of Southern Africa), and have adapted to this harsh environment as caudex-forming, perennial caudiciformes, including Dioscorea elephantipes, the "elephant's foot" or "elephant-foot yam".

Older systems tended to place all lilioid monocots with reticulate veined leaves (such as Smilacaceae and Stemonaceae together with Dioscoraceae) in Dioscoreales; as currently circumscribed by phylogenetic analysis, using combined morphology and molecular methods, Dioscreales now contains many reticulate-veined vines within the Dioscoraceae, as well as the myco-heterotrophic Burmanniaceae and the autotrophic Nartheciaceae.

Description

Dioscoreales are vines or herbaceous forest floor plants. They may be achlorophyllous or saprophytic. Synapomorphies include tuberous roots, glandular hairs, seed coat characteristics and the presence of calcium oxalate crystals.[5] Other characteristics of the order include the presence of saponin steroids, annular vascular bundles that are found in both the stem and leaf. The leaves are often unsheathed at the base, have a distinctive petiole and reticulate veined lamina. Alternatively they may be small and scale-like with a sheathed base. The flowers are actinomorphic, and may be bisexual or dioecious, while the flowers or inflorescence bear glandular hairs. The perianth may be conspicuous or reduced and the style is short with well developed style branches. The tepals persist in the development of the fruit, which is a dry capsule or berry. In the seed, the endotegmen is tanniferous and the embryo short.[6]

All of the species except the genera placed in Nartheciaceae express simultaneous microsporogenesis. Plants in Nartheciaceae show successive microsporogenesis which is one of the traits indicating that the family is sister to all the other members included in the order.

Taxonomy

Pre-Darwinian

For the early history from Lindley (1853)[7] onwards, see Caddick et al. (2000) Table 1,[8] Caddick et al. (2002a) Table 1[5] and Table 2 in Bouman (1995).[9] The taxonomic classification of Dioscoreales has been complicated by the presence of a number of morphological features reminiscent of the dicotyledons, leading some authors to place the order as intermediate between the monocotyledons and the dicotyledons.[9]

While Lindley did not use the term "Dioscoreales", he placed the family Dioscoraceae together with four other families in what he referred to as an Alliance (the equivalent of the modern Order) called Dictyogens. He reflected the uncertainty as to the place of this Alliance by placing it as a class of its own between Endogens (monocots) and Exogens (dicots)[10] The botanical authority is given to von Martius (1835) by APG for his description of the family Dioscoreae or Ordo,[3] while other sources[11] cite Hooker (Dioscoreales Hook.f.) for his use of the term "Dioscorales" in 1873[12] with a single family, Dioscoreae.[13] However, in his more definitive work, the Genera plantara (1883), he simply placed Dioscoraceae in the Epigynae "Series".[14]

Post-Darwinian

Although Charles Darwin's Origin of Species (1859) preceded Bentham and Hooker's publication, the latter project was commenced much earlier and George Bentham was initially sceptical of Darwinism.[15] The new phyletic approach changed the way that taxonomists considered plant classification, incorporating evolutionary information into their schemata, but this did little to further define the circumscription of Dioscoreaceae. The major works in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century employing this approach were in the German literature. Authors such as Eichler,[16] Engler[17] and Wettstein[18] placed this family in the Liliiflorae, a major subdivision of monocotyledons. it remained to Hutchinson (1926)[19] to resurrect the Dioscoreales to group Dioscoreaceae and related families together. Hutchinson's circumscription of Dioscoreales included three other families in addition to Dioscoreaceae, Stenomeridaceae, Trichopodaceae and Roxburghiaceae. Of these only Trichopodaceae was included in the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (APG) classification (see below), but was subsumed into Dioscoraceae. Stenomeridaceae, as Stenomeris was also included in Dioscoreaceae as subfamily Stenomeridoideae, the remaining genera being grouped in subfamily Dioscoreoideae.[9] Roxburghiaceae on the other hand was segregated in the sister order Pandanales as Stemonaceae. Most taxonomists in the twentieth century (the exception was the 1981 Cronquist system which placed most such plants in order Liliales, subclass Liliidae, class Liliopsida=monocotyledons, division Magnoliophyta=angiosperms) recognised Dioscoreales as a distinct order, but demonstrated wide variations in its composition.[5][9]

Dahlgren, in the second version of his taxonomic classification (1982)[20] raised the Liliiflorae to a superorder and placed Dioscoreales as an order within it. In his system, Dioscoreales contained only three families, Dioscoreaceae, Stemonaceae (i.e. Hutchinson's Roxburghiaceae) and Trilliaceae. The latter two families had been treated as a separate order (Stemonales, or Roxburghiales) by other authors, such as Huber (1969).[21] The APG would later assign these to Pandanales and Liliales respectively. Dahlgren's construction of Dioscoreaceae included the Stenomeridaceae and Trichopodaceae, doubting these were distinct, and Croomiaceae in Stemonaceae. Furthermore, he expressed doubts about the order's homogeneity, especially Trilliaceae. The Dioscoreales at that time were marginally distinguishable from the Asparagales. In his examination of Huber's Stemonales, he found that the two constituent families had as close an affinity to Dioscoreaceae as to each other, and hence included them. He also considered closely related families and their relationship to Dioscoreales, such as the monogeneric Taccaceae, then in its own order, Taccales. Similar considerations were discussed with respect to two Asparagales families, Smilacaceae and Petermanniaceae.[20]

In Dahlgren's third and final version (1985)[22] that broader circumscription of Dioscoreales was created within the superorder Lilianae, subclass Liliidae (monocotyledons), class Magnoliopsida (angiosperms) and comprised the seven families Dioscoreaceae, Petermanniaceae, Smilacaceae, Stemonaceae, Taccaceae, Trichopodaceae and Trilliaceae. Thismiaceae has either been treated as a separate family closely related to Burmanniaceae or as a tribe (Thismieae) within a more broadly defined Burmanniaceae, forming a separate order, Burmanniales, in the Dahlgren system.[23] The related Nartheciaceae were treated as tribe Narthecieae within the Melanthiaceae in a third order, the Melanthiales, by Dahlgren.[22] Dahlgren considered the Dioscoreales to most strongly resemble the ancestral monocotyledons, and hence sharing "dicotyledonous" characteristics, making it the most central monocotyledon order.[9] Of these seven families, Bouman considered Dioscoreaceae, Trichopodaceae, Stemonaceae and Taccaceae to represent the "core" families of the order. However, that study also indicated both a clear delineation of the order from other orders particularly Asparagales, and a lack of homogeneity within the order.[9]

Molecular phylogenetics and the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group

The increasing availability of molecular phylogenetics methods in addition to morphological characteristics in the 1990s led to major reconsiderations of the relationships within the monocotyledons.[24] In that large multi-institutional examination of the seed plants using the plastid gene rbcL the authors used Dahlgren's system as their basis, but followed Thorne (1992)[25] in altering the suffixes of the superorders from "-iflorae" to "-anae".[lower-alpha 1] This demonstrated that the Lilianae comprised three lineages corresponding to Dahlgren's orders Dioscoreales, Liliales, and Asparagaless.

Under the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group system of 1998,[26] which took Dahlgren's system as a basis, the order was placed in the monocot clade and comprised the five families Burmanniaceae, Dioscoreaceae, Taccaceae, Thismiaceae and Trichopodaceae.

In APG II (2003),[27] a number of changes were made to Dioscoreales, as a result of an extensive study by Caddick and colleagues (2002),[5][28] using an analysis of three genes, rbcL, atpB and 18S rDNA, in addition to morphology. These studies resulted in a re-examination of the relationships between most of the genera within the order. Thismiaceae was shown to be a sister group to Burmanniaceae, and so was included in it. The monotypic families Taccaceae and Trichopodaceae were included in Dioscoreaceae, while Nartheciaceae could also be grouped within Dioscoreales. APG III (2009)[29] did not change this, so the order now comprises three families Burmanniaceae, Dioscoreaceae and Nartheciaceae.

Although further research on the deeper relationships within Dioscoreales continues,[30][31][23] the APG IV (2016) authors felt it was still premature to propose a restructuring of the order. Specifically these issues involve conflicting information as to the relationship between Thismia and Burmanniaceae,[32] and hence whether Thismiaceae should be subsumed in the latter, or reinstated.[1]

Phylogeny

Molecular phylogenetics in Dioscoreales poses special problems due to the absence of plastid genes in mycoheterotrophs.[30] Dioscoreales is monophyletic and is placed as a sister order to Pandanales, as shown in Cladogram I.[32][1]

| Cladogram I: The phylogenetic composition of the monocots.[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Evolution

The data for the evolution of the order is collected from molecular analyses since there are no such fossils found. It is estimated that Dioscoreales and its sister clade Pandanales split up around 121 million years ago during Early Cretaceous when the stem group was formed. Then it took 3 to 6 million years for the crown group to differentiate in Mid Cretaceous.

Subdivision

The three families of Dioscreales constitutes about 22 genera and about 849 species[33] making it one of the smaller monocot orders.[31] Of these, the largest group is Dioscorea (yams) with about 450 species. By contrast the second largest genus is Burmannia with about 60 species, and most have only one or two.[31]

Some authors,[23] preferring the original APG (1998)families, continue to treat Thismiaceae separately from Burmanniaceae and Taccaceae from Dioscoreaceae.[31] But in the 2015 study of Hertwerk and colleagues, seven genera representing all three families were examined with an eight gene dataset. Dioscoreales was monophyletic and three subclades were represented corresponding to the APG families. Dioscoreaceae and Burmanniaceae were in a sister group relationship.[32]

| Cladogram II: Relationship of Dioscoreales families[32] (number of genera)[33] | |||||||||||||||

|

Etymology

Named after the type genus Dioscorea, which in turn was named by Linnaeus in 1753 to honour the Greek physician and botanist Dioscorides.[9]

Distribution and habitat

Species from this order are distributed across all of the continents except Antarctica. They are mainly tropical or subtropical representatives, but some members of families Dioscoreaceae and Nartheciaceae are found in cooler regions of Europe and North America. Order Dioscoreales contains plants that are able to form an underground organ for reservation of nutritions as many other monocots. An exception is the family Burmanniaceae which is entirely myco-heterotrophic and contains species that lack photosynthetic abilities.

Ecology

The three families included in order Dioscoreales also represent three different ecological groups of plants. Dioscoreaceae contains mainly vines (Dioscorea) and other crawling species (Epipetrum). Nartheciaceae on the other hand is a family composed of herbaceous plants with a rather lily-like appearance (Aletris) while Burmanniaceae is entirely myco-heterotrophic group.

Uses

Many members of Dioscoreaceae produce tuberous starchy roots (yams) which form staple foods in tropical regions. They have also been the source of steroids for the pharmaceutical industry, including the production of oral contraceptives.

Notes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 APG IV 2016.

- ↑ Tropicos 2015, Dioscoreales Mart.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Martius 1835, Ordo 42. Dioscore R. Br. p. 9

- ↑ LAPGIII 2009.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Caddick et al 2002a.

- ↑ Stevens 2016, Dioscoreales

- ↑ Lindley 1853.

- ↑ Caddick et al 2000.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 Bouman 1995.

- ↑ Lindley 1853, Dictyogens p. 211

- ↑ Brands 2015, Dioscoreales (Order)

- ↑ Le Maout & Decaisne 1873, Cohort VI. Dioscorales p. 1018

- ↑ Le Maout & Decaisne 1873, XV Dioscoreae p. 794

- ↑ Bentham & Hooker 1862–1883, vol. 3 part 2 Ordo Dioscoreaceae p. 741

- ↑ Stuessy 2009, Natural classification p. 47

- ↑ Eichler 1886, Dioscoreaceae p. 35

- ↑ Engler 1903, Dioscoreaceae p. 99

- ↑ Wettstein 1924, Dioscoreaceae p. 880

- ↑ Hutchinson 1959.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Dahlgren & Clifford 1982.

- ↑ Huber 1969.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Dahlgren, Clifford & Yeo 1985.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Merckx & Smets 2014.

- ↑ Chase et al 1993.

- ↑ Thorne 1992.

- ↑ APG I 1998.

- ↑ APG II 2003.

- ↑ Caddick et al 2002b.

- ↑ APG III 2009.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Merckx et al 2009.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 Merckx et al 2010.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 Hertweck et al 2015.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Christenhusz & Byng 2016.

Bibliography

Articles and chapters

- Bouman, F. Seed Structure and Systematics in Dioscoreales. pp. 139–156., In (Rudall et al 1995)

- Caddick, LR; Rudall, PJ; Wilkin, P; Chase, MW. Yams and their allies: systematics of Dioscoreales. pp. 475–487., In (Wilson Morrison)

- Caddick, Lizabeth R.; Rudall, Paula J.; Wilkin, Paul; Hedderson, Terry A. J.; Chase, Mark W. (February 2002), "Phylogenetics of Dioscoreales based on combined analyses of morphological and molecular data", Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 138 (2): 123–144, doi:10.1046/j.1095-8339.2002.138002123.x

- Caddick, Lizabeth R.; Wilkin, Paul; Rudall, Paula J.; Hedderson, Terry A. J.; Chase, Mark W. (February 2002), "Yams Reclassified: A Recircumscription of Dioscoreaceae and Dioscoreales", Taxon 51 (1): 103, doi:10.2307/1554967

- Chase, Mark W.; Soltis, Douglas E.; Olmstead, Richard G.; Morgan, David; Les, Donald H.; Mishler, Brent D.; Duvall, Melvin R.; Price, Robert A. et al. (1993). "Phylogenetics of Seed Plants: An Analysis of Nucleotide Sequences from the Plastid Gene rbcL". Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 80 (3): 528. doi:10.2307/2399846. https://spectrum.library.concordia.ca/6741/1/Dayanandan_AnnalsMissouriBotanicalGardens_1993.pdf.

- Christenhusz, Maarten JM; Byng, J. W. (2016). "The number of known plants species in the world and its annual increase". Phytotaxa 261 (3): 201–217. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.261.3.1. http://biotaxa.org/Phytotaxa/article/download/phytotaxa.261.3.1/20598.

- Dahlgren, R. M. T. (February 1980). "A revised system of classification of the angiosperms". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 80 (2): 91–124. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1980.tb01661.x.

- Haston, Elspeth; Richardson, James E.; Stevens, Peter F.; Chase, Mark W.; Harris, David J. (2009). "The Linear Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (LAPG) III: a linear sequence of the families in APG III". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 161 (2): 128–131. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2009.01000.x.

- Hertweck, Kate L.; Kinney, Michael S.; Stuart, Stephanie A.; Maurin, Olivier; Mathews, Sarah; Chase, Mark W.; Gandolfo, Maria A.; Pires, J. Chris (July 2015). "Phylogenetics, divergence times and diversification from three genomic partitions in monocots". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 178 (3): 375–393. doi:10.1111/boj.12260.

- Huber, H (1969). "Die Samenmerkmale und Verwandtschaftsverhältnisse der Liliifloren" (in de). Mitt. Bot. Staatssamml.[Mitteilungen der Botanischen Staatssammlung München] 8: 219–538. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/52263#page/639/mode/1up. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- Merckx, V.; Schols, P.; Kamer, H. M.-v. d.; Maas, P.; Huysmans, S.; Smets, E. (1 November 2006). "Phylogeny and evolution of Burmanniaceae (Dioscoreales) based on nuclear and mitochondrial data". American Journal of Botany 93 (11): 1684–1698. doi:10.3732/ajb.93.11.1684. PMID 21642114. http://www.repository.naturalis.nl/document/447930.

- Merckx, Vincent S. F. T.; Smets, Erik F. (February 2014), "Thismia americana, the 101st Anniversary of a Botanical Mystery", International Journal of Plant Sciences 175 (2): 165–175, doi:10.1086/674315

- Merckx, Vincent; Bakker, Freek T.; Huysmans, Suzy; Smets, Erik (February 2009). "Bias and conflict in phylogenetic inference of myco-heterotrophic plants: a case study in Thismiaceae". Cladistics 25 (1): 64–77. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2008.00241.x. PMID 34879617. https://lirias.kuleuven.be/handle/123456789/249090.

- Merckx, V; Huysmans, S; Smets, EF. Cretaceous origins of mycoheterotrophic lineages in Dioscoreales. pp. 39–53. http://www.binco.eu/burmannia/Vincent_Merckx/Publications_files/Monocots%202010%20Merckx.pdf. Retrieved 31 January 2016., In (Seberg et al 2010)

- Schols, Peter; Furness, Carol A.; Merckx, Vincent; Wilkin, Paul; Smets, Erik (November 2005). "Comparative Pollen Development in Dioscoreales". International Journal of Plant Sciences 166 (6): 909–924. doi:10.1086/449316. http://www.repository.naturalis.nl/document/351560.

- Seberg, Ole; Petersen, Gitte; Barfod, Anders et al., eds (2010). Diversity, phylogeny, and evolution in the Monocotyledons: proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on the Comparative Biology of the Monocotyledons and the Fifth International Symposium on Grass Systematics and Evolution. Århus: Aarhus University Press. ISBN 978-87-7934-398-6. http://en.unipress.dk/udgivelser/d/diversity,-phylogeny,-and-evolution-in-the-monocotyledons/.

- Thorne, R. F. (1992). "Classification and geography of the flowering plants". The Botanical Review 58 (3): 225–348. doi:10.1007/BF02858611.

Books and symposia

- Bentham, G.; Hooker, J.D. (1862–1883) (in la). Genera plantarum ad exemplaria imprimis in herbariis kewensibus servata definita. London: L Reeve & Co.. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/747#/summary. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- Dahlgren, Rolf; Clifford, H. T. (1982). The monocotyledons: A comparative study. London and New York: Academic Press. https://books.google.com/books?id=coXwAAAAMAAJ.

- Dahlgren, R.M.; Clifford, H.T.; Yeo, P.F. (1985). The families of the monocotyledons. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-642-64903-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=3iGndTFY0skC. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- Eichler, August W. (1886) (in de). Syllabus der Vorlesungen über specielle und medicinisch-pharmaceutische Botanik (4th ed.). Berlin: Borntraeger. https://books.google.com/books?id=XE0bAAAAYAAJ.

- Engler, Adolf (1903) (in de). Syllabus der Pflanzenfamilien : eine Übersicht über das gesamte Pflanzensystem mit Berücksichtigung der Medicinal- und Nutzpflanzen nebst einer Übersicht über die Florenreiche und Florengebiete der Erde zum Gebrauch bei Vorlesungen und Studien über specielle und medicinisch-pharmaceutische Botanik (3rd ed.). Berlin: Borntraeger. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/63778#page/7/mode/1up. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- Hutchinson, John (1959). The families of flowering plants, arranged according to a new system based on their probable phylogeny. 2 vols. (2nd ed.). Macmillan.

- Le Maout, Emmanuel; Decaisne, Joseph (1873). Hooker, Joseph Dalton. ed. A General System of Botany, Descriptive and Analytical in two parts. trans. Frances Harriet Hooker. London: Longmans Green. https://archive.org/details/cu31924001400484.

- Lindley, John (1853). The Vegetable Kingdom: or, The structure, classification, and uses of plants, illustrated upon the natural system (3rd. ed.). London: Bradbury & Evans. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/95459#/summary. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- Martius, Karl Friedrich Philipp von (1835) (in la, de). Conspectus regni vegetabilis: secundum characteres morphologicos praesertim carpicos in classes ordines et familias digesti.... Nuremberg: Schrag. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/7730#/summary. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- Rudall, P.J.; Cribb, P.J.; Cutler, D.F. et al., eds (1995). Monocotyledons: systematics and evolution (Proceedings of the International Symposium on Monocotyledons: Systematics and Evolution, Kew 1993). Kew: Royal Botanic Gardens. ISBN 978-0-947643-85-0. http://www.press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/distributed/M/bo9856357.html. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- Stuessy, Tod F. (2009). Plant Taxonomy: The Systematic Evaluation of Comparative Data. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14712-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=0bYs8F0Mb9gC. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- Wettstein, Richard (1924) (in de). Handbuch der Systematischen Botanik 2 vols. (3rd ed.). http://biolib.mpipz.mpg.de/library/authors/author_00267_de.html. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- Wilson, K. L.; Morrison, D. A., eds. (2000), Monocots: Systematics and evolution (Proceedings of the Second International Conference on the Comparative Biology of the Monocotyledons, Sydney, Australia 1998), Collingwood, Australia: CSIRO, ISBN 978-0-643-06437-9, http://www.publish.csiro.au/pid/2424.htm, retrieved 14 January 2014

Databases

- Brands, S.J. (2015). "The Taxonomicon". Universal Taxonomic Services, Zwaag, The Netherlands. http://taxonomicon.taxonomy.nl/Default.aspx.

- Stevens, P.F. (2016), Angiosperm Phylogeny Website, Missouri Botanical Garden, http://www.mobot.org/mobot/research/APWeb/, retrieved 22 June 2016

- "Tropicos". Missouri Botanical Garden. 2015. http://www.tropicos.org/Home.aspx.

- IPNI (2015). "The International Plant Names Index". http://www.ipni.org/index.html.

APG

- APG I (1998). "An ordinal classification for the families of flowering plants". Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 85 (4): 531–553. doi:10.2307/2992015. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/part/2234.

- APG II (2003). "An Update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group Classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG II". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 141 (4): 399–436. doi:10.1046/j.1095-8339.2003.t01-1-00158.x.

- APG III (2009). "An Update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG III". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 161 (2): 105–121. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2009.00996.x.

- APG IV (2016). "An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 181 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1111/boj.12385.

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q747698 entry

|