Biology:Epiphysis

| Epiphysis | |

|---|---|

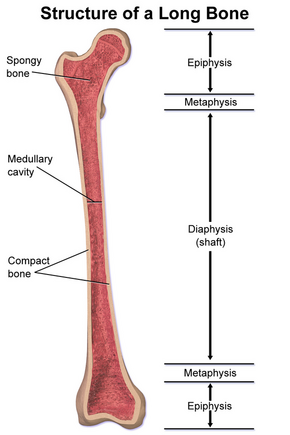

Structure of a long bone, with epiphysis labeled at top and bottom. | |

| Details | |

| Pronunciation | /ɛˈpɪfɪsɪs/[1][2] |

| Part of | Long bones |

| Anatomical terminology | |

An epiphysis (from grc ἐπί (epí) 'on top of', and φύσις (phúsis) 'growth'; pl.: epiphyses) is one of the rounded ends or tips of a long bone that ossify from a secondary center of ossification.[3][4] Between the epiphysis and diaphysis (the long midsection of the long bone) lies the metaphysis, including the epiphyseal plate (growth plate). At the joint, the epiphysis is covered with articular cartilage; below that covering is a zone similar to the epiphyseal plate, known as subchondral bone. In evolution, reptiles do not have epiphyses and diaphyses, being restricted to mammals.

The epiphysis is filled with red bone marrow, which produces erythrocytes (red blood cells).

Structure

There are four types of epiphysis:

- Pressure epiphysis: The region of the long bone that forms the joint is a pressure epiphysis (e.g. the head of the femur, part of the hip joint complex). Pressure epiphyses assist in transmitting the weight of the human body and are the regions of the bone that are under pressure during movement or locomotion. Another example of a pressure epiphysis is the head of the humerus which is part of the shoulder complex. condyles of femur and tibia also comes under the pressure epiphysis.

- Traction epiphysis: The regions of the long bone which are non-articular, i.e. not involved in joint formation. Unlike pressure epiphyses, these regions do not assist in weight transmission. However, their proximity to the pressure epiphysis region means that the supporting ligaments and tendons attach to these areas of the bone. Traction epiphyses ossify later than pressure epiphyses. Examples of traction epiphyses are tubercles of the humerus (greater tubercle and lesser tubercle), and trochanters of the femur (greater and lesser).

- Atavistic epiphysis: A bone that is independent phylogenetically but is fused with another bone in humans. These types of fused bones are called atavistic, e.g., the coracoid process of the scapula, which has been fused in humans, but is separate in four-legged animals. os trigonum (posterior tubercle of talus) is another example for atavistic epiphysis.

- Aberrant epiphysis: These epiphyses are deviations from the norm and are not always present. For example, the epiphysis at the head of the first metacarpal bone and at the base of other metacarpal bones

Bones with an epiphysis

There are many bones that contain an epiphysis:

- Humerus: Located between the shoulder and the elbow.

- Radius: One of two bones located between the hand and the elbow. In anatomical position, the radius is lateral to the ulna.

- Ulna: One of two bones located between the hand and the elbow. In anatomical position, the ulna is medial to the radius.

- Metacarpal: Bones of the hand. They are proximal to the phalanges of the hand.

- Phalanges: Bones of the fingers and toes. They are distal to the metacarpals in the hand and metatarsals in the foot.

- Femur: Longest bone in the human body. Located in the thigh region, between the hip and the knee.

- Fibula: One of two bones in the lower leg. It is lateral to the tibia and smaller.

- Tibia: One of two bones in the lower leg. It is medial to the fibula and does most of the weight bearing.

- Metatarsal: Bones of the foot. Distal to the medial cuneiform on the first metatarsal, and proximal to the phalanges for the other four.

Pseudo-epiphysis

A pseudo-epiphysis is an epiphysis-looking end of a bone where an epiphysis is not normally located.[6] A pseudo-epiphysis is delineated by a transverse notch, looking similar to a growth plate.[6] However, these transverse notches lack the typical cell columns found in normal growth plates, and do not contribute significantly to longitudinal bone growth.[7] Pseudo-epiphyses are found at the distal end of the first metacarpal bone in 80% of the normal population, and at the proximal end of the second metacarpal in 60%.[6]

Clinical significance

Pathologies of the epiphysis include avascular necrosis and osteochondritis dissecans (OCD). OCD involves the subchondral bone.

Epiphyseal lesions include chondroblastoma and giant-cell tumor.[8]

Additional images

-

Long bone

-

Longitudinal section of head of left humerus.

References

- ↑ OED 2nd edition, 1989 as /εˈpɪfɪsɪs/.

- ↑ Entry "epiphysis" in Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary.

- ↑ Chaurasia, B. D. (2009). B D Chaurasia's Handbook of General Anatomy (4th ed.). Delhi, India: CBS. pp. 41. ISBN 978-8123916545. OCLC 696622496. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/696622496.

- ↑ "Epiphysis | Definition, Anatomy, & Function | Britannica" (in en). https://www.britannica.com/science/epiphysis.

- ↑ Mathis, SK; Frame, BA; Smith, CE (1989). "Distal first metatarsal epiphysis. A common pediatric variant". Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association 79 (8): 375–379. doi:10.7547/87507315-79-8-375. ISSN 8750-7315. PMID 2681682.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Page 163 in: Giuseppe Guglielmi, Cornelis Van Kuijk (2001). Fundamentals of Hand and Wrist Imaging. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9783540678540.

- ↑ Ogden, J.A.; Ganey, T.M.; Light, T.R.; Belsole, R.J.; Greene, T.L. (1994). "Ossification and pseudoepiphysis formation in the ?nonepiphyseal? end of bones of the hands and feet". Skeletal Radiology 23 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1007/BF00203694. ISSN 0364-2348. PMID 8160033.

- ↑ "Introductory Course". http://www.umdnj.edu/tutorweb/introductory.htm.

|