Biology:Haversian canal

| Haversian canal | |

|---|---|

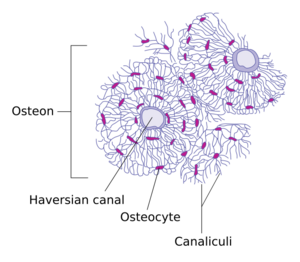

Diagram of compact bone from a transverse section of a typical long bone's cortex. | |

| Anatomical terminology |

Haversian canals[lower-roman 1] (sometimes canals of Havers or central canals) are a series of microscopic tubes in the outermost region of bone called cortical bone. They allow blood vessels and nerves to travel through them to supply the osteocytes.

Structure

Each Haversian canal generally contains one or two capillaries and many nerve fibres. The channels are formed by concentric layers called lamellae, which are approximately 50 µm in diameter. The Haversian canals surround blood vessels and nerve cells throughout bones and communicate with osteocytes (contained in spaces within the dense bone matrix called lacunae) through connections called canaliculi. This unique arrangement is conducive to mineral salt deposits and storage which gives bone tissue its strength. Active transport is used to move most substances between the blood vessels and the osteocytes.[1]

Haversian canals are contained within osteons, which are typically arranged along the long axis of the bone in parallel to the surface. The canals and the surrounding lamellae (8-15) form the functional unit, called a Haversian system, or osteon.

Clinical significance

Fracture

Blood vessels in the Haversian canals are likely to be damaged by bone fracture.[2] This can cause haematoma.[2]

Rheumatoid arthritis

Haversian canals may be wider in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.[3] They are also more likely to contain osteoclasts that break down bone structure.[3] These differences are studied with light microscopy.[3]

History

Haversian canals were first described (and probably discovered) by England physician Clopton Havers, after whom they are named.[4] He described them in his 1691 work Osteologica Nova.[5]

In different animals

Human bones are densely vascularized as in many other mammals. Even though some authors tried to identify a correlation between endothermy and secondary Haversian reconstruction, this feature is absent in many living mammals (e.g. monotremes, Talpa, flying foxes, Herpestes, Dasypus) and birds (Aratinga, Morococcyx, Nyctidromus, Momotus, Chloroceryle) while others possess only scattered Haversian systems (e.g. artiodactyls, Didelphis, Anas, Gallus, turkey, helmeted guineafowl). Scattered Haversian canals are also found in ectotherms like cryptodire turtles.[6] Among extinct groups, dense Haversian vascularization is only present in stem-birds (dinosaurs) and stem-mammals (therapsids)[7] while scattered Haversian systems can be found in ichthyosaurs, phytosaurs, basal stem-mammals (e.g. Ophiacodon), Limnoscelis, and temnospondyls. When endosteal Haversian systems are considered, the phylogenetic distribution becomes even broader.[6]

Notes

- ↑ As with other medical eponyms, the adjective derived from the eponym's name is usually lowercased; thus haversian (but canal of Havers), fallopian, eustachian, and parkinsonism (but Parkinson disease); for more, see eponym > orthographic conventions.

References

- ↑ Dahl, A. C. E.; Thompson, M. S. (2011-01-01), Moo-Young, Murray, ed., "5.18 - Mechanobiology of Bone" (in en), Comprehensive Biotechnology (Second Edition) (Burlington: Academic Press): pp. 217–236, ISBN 978-0-08-088504-9, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780080885049004190, retrieved 2021-01-15

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 White, Tim D.; Folkens, Pieter A. (2005-01-01), White, Tim D.; Folkens, Pieter A., eds., "Chapter 4 - BONE BIOLOGY & VARIATION" (in en), The Human Bone Manual (San Diego: Academic Press): pp. 31–48, ISBN 978-0-12-088467-4, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780120884674500077, retrieved 2021-01-15

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Aeberli, D. (2014-01-01), "Skeleton, Inflammatory Diseases of" (in en), Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences (Elsevier), ISBN 978-0-12-801238-3, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B978012801238300026X, retrieved 2021-01-15

- ↑ Sparks, David S.; Saleh, Daniel B.; Rozen, Warren M.; Hutmacher, Dietmar W.; Schuetz, Michael A.; Wagels, Michael (2017-01-01). "Vascularised bone transfer: History, blood supply and contemporary problems" (in en). Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery 70 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2016.07.012. ISSN 1748-6815. PMID 27843061. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1748681516301723.

- ↑ Havers, Clopton (1729) (in en). Osteologia Nova: Or, Some New Observations of the Bones, and the Parts Belonging to Them; with the Manner of Their Accretion and Nutrition: Communicated to the Royal Society in Several Discourses ... To which is Added, a Fifth Discourse, of the Cartilages. The Second Edition. By Clopton Havers ... W. Innys. https://books.google.com/books?id=tx52uqkSVzIC&pg=PA7.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Bouvier, Marianne (1977). "DINOSAUR HAVERSIAN BONE AND ENDOTHERMY" (in en). Evolution 31 (2): 449–450. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1977.tb01028.x. https://academic.oup.com/evolut/article/31/2/449/6871095.

- ↑ Enlow, Donald H. (1969). "The bones of reptiles" (in en). Biology of the Reptilia. 1. Academic Press. pp. 45-81.

External links

- http://www.lab.anhb.uwa.edu.au/mb140/

- "Bone Anatomy - Haversian canals within bone". November 4, 2006. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XtV7GdogTPA. Video of haversian canal system within cortical bone.

Additional images

|