Biology:Foetal brain cell graft

Foetal brain cell graft is a surgical procedure that can be used as a regenerative treatment for various neurological conditions, but was mainly explored and used specifically for treating Parkinson's disease (PD).[1] A standardised procedure is followed: the cells are usually obtained from a 7–8 weeks old foetus and the collected cells undergo testing to examine whether they are free from infectious agents and safe for transplantation.[2] It is found that this procedure results in an overall improvement in motor functions and a reduction in reliance on medication for PD patients.

Foetal brain cells are unique as they are multi-potent and proliferate faster. However, there are several factors that influence the success of the procedure; if the foetal neurons are not completely functionally integrated in the host, it may cause various side effects, which are the risks and limitations associated with this procedure.[3][4] Ethical issues raised regarding this procedure include its influence on the mother's decision for abortion, leading to a rise in abortion rates.[5] Deriving stem cells from foetuses may also violate human dignity.[6]

Grafting

Grafting is a surgical procedure involving the replacement of damaged or missing body tissues from a healthy body, in which blood supply of the surgical area integrates with the neighbouring cells in the body.[7] In brief, the procedure is to first obtain cells from a healthy donor, and then anaesthetise the patient and make an incision on the target area, for easier access. Lastly, close the incision with stitches.[citation needed]

Foetal tissue transplantation

Stem cells found in the foetal tissues can differentiate into any cell type. Foetal tissue transplantation is a foetal allograft procedure, using tissues from an aborted foetus and implanting it into a diseased patient’s body to improve defective tissue functioning.[8]

In 1928, one of the first foetal tissue transplantation attempt was made in Italy using aborted foetal tissues. After lots of trial and error, bone marrow transplantation became successful in the 1970s, where there were no infectious complications or transplant rejection. Foetal tissues have also been used in liver and thymus transplantations (1968).[5] The widespread success of foetal tissue transplantation led to the use of foetal brain cells to treat neurological diseases.

Foetal brain cells

Foetal cells are differentiated stem cells from pluripotent embryonic stem cells. They are found in one of the three germ layers of the embryo[9] and shows multipotency. Human foetal tissues have been widely used in transplantations to treat various conditions,[5] which is mainly due to its unique properties, containing a rich source of primordial stem cells. In comparison to adult (mature) stem cells, foetal stem cells’ proliferation rate is much faster and have greater plasticity in differential potential. This suggests that the lost functions of the host cells can be recovered relatively quickly by the donor cells within a short period of time. Also, foetal cells differentiate in response to their surrounding environment, and their location plays a key role, for instance, the functional connections they establish, their growth, elongation and migration are facilitated by the location and environmental cues. Due to the presence of low levels of histocompatibility antigens in foetal cells, the chances of the recipient rejecting the transplanted foetal cell is very low. It is also found that foetal cells can produce high levels of angiogenic and neurotrophic factors, which increases their growth rate after transplantation. As foetal cells have short extensions and weak intercellular connections, they survive better after grafting. Lastly, the cells can survive in lower oxygen conditions, and tend to be more resistant to ischemic environments during transplantation or in vitro conditions.[10]

Procedure

Generally, cells are harvested from foetuses at around 7 to 8 weeks of age,[11] but it is also possible to collect the cells from the foetus any time between 8 and 12 weeks.[2] Cells are obtained from dead foetuses, in which their cause of death is usually due to stillbirth, abortion or atopic pregnancy through surgery. The collected cells first undergo in vitro culture to check for any gene abnormalities and cell dysfunctions, then the cells will be injected into the patient through implantation surgeries. Immunosuppressants are used to avoid immune rejection of cells.[5]

Collecting foetal brain cells

To access the ventral midbrain for tissue dissection, cover tissues are removed from the aborted foetus. The dissection is targeted to isolate homogenous cell types from group of tissues in the brain. Cells dissected are glial cells that regulate the neurons' growth, and synaptic connections.

Processing of the cells

The harvesting of cells from foetuses are done according to the standardised stem cell protocol, this includes the following:[2]

- Place isolated cells on ice

- Calculate cell viability

- Culture cells to transform into a suspension

- Grind to dissolve cells

- Number and size of clones increases over time

After a week of culturing, around 40 to 50% of the cells do not survive in vitro.

These cells are stored for 6 weeks at low temperatures (cryopreservation) to keep cool. The cells are further examined whether they are clear of infectious agents, to ensure that they are safe to use. At this stage, the level of dopamine released from the cells is measured, as dopamine is needed for the treatment of PD. Patient's physical health is also monitored in the meantime, which aids the physician to determine the optimal time and physical state for performing the graft.[2]

Implantation of the cells

MRI is used to examine the anatomy (shape and location for the insertion of cells) of the human brain prior to the surgery. This examination is essential as it ensures that the insertion of foetal cells is done at the target location. The duration of this procedure roughly takes 6 hours. It is operated under general anaesthesia, where the grafts are implanted directly into the striatum. After monitoring the patient's physical state, they are usually discharged from the hospital within a day.[2]

Determinants of success in foetal brain cell graft

The survival of the cells is influenced by the age of the donor tissue and the stage at which cells are extracted. In addition, tests for cytogenetic abnormalities, viability of foetal cells and differentiation of the cells in patients, as well as long-term follow ups are needed to determine success. Successful grafting of 100,000 neurons in each putamen, and functional integration into the host basal ganglia synthesises dopamine, which leads to desirable outcomes.[3]

Side effects and limitations

Side effects

In 2001, a New York Times article reported that patients with PD who underwent the foetal brain cell graft showed uncontrollable muscle movements and other adverse events.[4]

In 2003, another study reported that post-foetal brain cell graft, patients developed tremors. The procedure showed no effectiveness, instead grafted cells homogenised with the environment and developed morphological and functional features of the affected PD cells. A patient with Huntington disease was treated with foetal brain cells which led to a brain tumour due to graft overgrowth.[4]

Limitations

Due to the difficulty in obtaining healthy foetal tissues, and the cost of surgery, only a few patients with PD can treated per year. Hence, this procedure cannot be used as a first-line treatment for treating a large population.[11]

Parkinson's disease and foetal brain cell grafting

Parkinson's disease (PD)

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a type of progressive age-related neurodegenerative disease.[12] It is resulted from the loss of dopaminergic neurons projecting from the substantia nigra pars compacta, and initiates a functional change in the dorsal (motor) striatum in the basal ganglia.[13] Dopamine neurons are found in the substantia nigra which sends signals to the striatum and specifically with caudate and putamen areas.[11] Symptoms of PD includes motor impairments, and behavioural changes.[12] The underlying mechanism of PD is proposed to be due to the changes in neurotransmitters, including the levels of dopamine and serotonin. The exploration of these mechanisms gives a clearer direction for new therapeutic target approaches.[12]

History of using foetal brain cell grafting for PD

In the early 1980s, only the surviving cell counts were reported for this procedure. Cellular characteristics, functions of the cells and their infectious ability were not examined. The screening stage for foetal brain cells was absent. Therefore, testing on animal models was needed to ensure the safety on humans.[5]

Between 1988 and 1994, this was a period of trial and testing on PD patients, which revealed several issues with the transplantation. For example, a patient who received foetal brain cells from 3 foetuses died post-surgery. In 2001, dopaminergic neurons were transplanted from foetal brains to PD patients and a full report on the clinical trial reported adverse events such as jerking and uncontrolled movements. Another attempt was documented by a report in 2009, where it showed no signs of improvement in the patients.[4]

Potential treatment for PD

Foetal brain cell graft is a potential therapeutic treatment for neurological diseases such as PD.[14] Currently, pharmaceutical interventions reduce the loss of striatal dopamine, and modulates dopamine (DA) neurotransmission (i.e., increasing DA levels in the brain). However, the use of these treatments is symptomatic, and do not address the underlying cause of the disease nor prevent the progressive degeneration of midbrain dopaminergic neurons (mDA) neurons. As PD progresses, these pharmaceutical interventions lose efficacy and result in greater side-effects.[15]

Foetal brain cell graft is a regenerative treatment that can replace the mDA neurons in PD patients at the time of diagnosis. This method allows the delivery of DA through a physiological manner and helps maintain the functions of other mDA neurons. A previous clinical trial documented a successful cell transplantation of human foetal ventral midbrain tissue and showed its efficacy in the concept of cell replacement therapy in PD.[15] Till now, results of foetal brain cell graft in treating PD has shown moderate success.[11]

Success rate of brain cell grafting

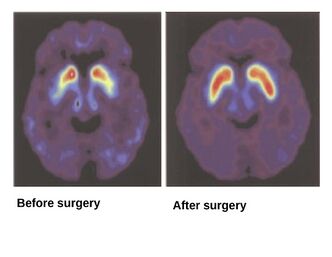

With technological advancements, foetal brain cell graft has shown significant improvements in patients with PD in recent years, as it reduces their medication dosage and the patients remained asymptomatic for over 20 years.[15]

A previous case study reported the success of the foetal brain cell grafting on 13 patients with PD in a Yale University funded Neural Transplant Programme. It followed the aforementioned standardised procedure for the graft. The tissues were collected from elective abortions, where the request for donation was made after the women’s decision to terminate pregnancy. The status of both the patients and the non-operated group were monitored during the follow-up period. It was observed that a few months post-surgery, motor functions were improved, and this effect lasted up to 2 years. The overall results of foetal brain cell graft showed benefits to patients with PD as it improved their performances and reduced their medication intake.[11]

Ethical implications

There are several ethical concerns associated with the procedure; it has been debated that the mother's decision for abortion may be influenced by the aspect of serving humanity by donating foetal tissues. The proponents also believe it heightens the possibility of women becoming pregnant and then aborting for the sole purpose of foetal tissues transplantation. Therefore, it affects the pregnant woman's decision to abort. Additionally, abortions might be done for financial purposes, which contributes to the rise in abortion rates.[16][5] Furthermore, the success of this procedure is not absolutely guaranteed, as transplantation rejections may occur due to infections or allergic reactions.

Another ethical consideration is that the foetus is considered human, and thus, the act of harvesting their brain cells violates human dignity. Moreover, if the success rate and acceptance of this procedure increases, in addition to the transplantation of foetal brain cells, it may potentially encourage the act of transplanting the entire foetal brain for medical purposes.[17]

References

- ↑ Li, Jia-Yi; Li, Wen (2021). "Postmortem Studies of Fetal Grafts in Parkinson's Disease: What Lessons Have We Learned?". Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 9. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.666675/full. ISSN 2296-634X

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Amariglio, Ninette; Hirshberg, Abraham; Scheithauer, Bernd W.; Cohen, Yoram; Loewenthal, Ron; Trakhtenbrot, Luba; Paz, Nurit; Koren-Michowitz, Maya et al. (2009-02-17). "Donor-derived brain tumor following neural stem cell transplantation in an ataxia telangiectasia patient". PLOS Medicine 6 (2): e1000029. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000029. ISSN 1549-1676. PMID 19226183.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 Lindvall, Olle (2003-02-01). "What Has Fetal Transplantation Taught Us About Cellular Transplantation Into the CNS?". Archives of Neurology 60 (2): 295–296. doi:10.1001/archneur.60.2.295-a. ISSN 0003-9942.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Institute, Charlotte Lozier (2015-07-27). "History of Fetal Tissue Research and Transplants" (in en-US). https://lozierinstitute.org/history-of-fetal-tissue-research-and-transplants/.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Ishii, Tetsuya; Eto, Koji (2014-09-26). "Fetal stem cell transplantation: Past, present, and future". World Journal of Stem Cells 6 (4): 404–420. doi:10.4252/wjsc.v6.i4.404. ISSN 1948-0210. PMID 25258662.

- ↑ Resnik, David B. (2007-03-29). "Embryonic stem cell patents and human dignity". Health Care Analysis 15 (3): 211–222. doi:10.1007/s10728-007-0045-9. ISSN 1065-3058. PMID 17922198.

- ↑ Griffin, R. Morgan. "What Are Grafts for Skin, Bone, Coronary Artery Bypass, Gums, and More" (in en). https://www.webmd.com/skin-problems-and-treatments/what-are-grafts.

- ↑ "Cell Transplantation (Mesencephalic, Adrenal-Brain and Fetal Xenograft)". https://www.southcarolinablues.com/web/public/brands/medicalpolicy/external-policies/cell-transplantation-mesencephalic-adrenal-brain-and-fetal-xenograft/.

- ↑ "Cell Potency: Totipotent vs Pluripotent vs Multipotent Stem Cells" (in en). http://www.technologynetworks.com/cell-science/articles/cell-potency-totipotent-vs-pluripotent-vs-multipotent-stem-cells-303218.

- ↑ Bhattacharya, N. (2004). "Fetal cell/tissue therapy in adult disease: a new horizon in regenerative medicine". Clinical and Experimental Obstetrics & Gynecology 31 (3): 167–173. ISSN 0390-6663. PMID 15491058. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15491058/.

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Applications, Institute of Medicine (US) Conference Committee on Fetal Research and (1994) (in en). Fetal Tissue Transplantation for Patients with Parkinson's Disease. National Academies Press (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK232006/.

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 12.2 Cechetto, D. F.; Jog, M. (2017-01-01), Cechetto, David F.; Weishaupt, Nina, eds., "Chapter 7 - Parkinson's Disease and the Cerebral Cortex" (in en), The Cerebral Cortex in Neurodegenerative and Neuropsychiatric Disorders (San Diego: Academic Press): pp. 177–193, ISBN 978-0-12-801942-9, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128019429000070, retrieved 2023-03-28

- ↑ Blandini, F.; Nappi, G.; Tassorelli, C.; Martignoni, E. (2000-09-01). "Functional changes of the basal ganglia circuitry in Parkinson's disease". Progress in Neurobiology 62 (1): 63–88. doi:10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00067-2. ISSN 0301-0082. PMID 10821982. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10821982/#:~:text=The%20basal%20ganglia%20circuitry%20processes,the%20whole%20basal%20ganglia%20network..

- ↑ Li, Jia-Yi; Li, Wen (2021). "Postmortem Studies of Fetal Grafts in Parkinson's Disease: What Lessons Have We Learned?". Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 9: 666675. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.666675. ISSN 2296-634X. PMID 34055800.

- ↑ Jump up to: 15.0 15.1 15.2 Ásgrímsdóttir, Emilía Sif; Arenas, Ernest (2020). "Midbrain Dopaminergic Neuron Development at the Single Cell Level: In vivo and in Stem Cells". Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 8: 463. doi:10.3389/fcell.2020.00463. ISSN 2296-634X. PMID 32733875.

- ↑ "WMA - The World Medical Association-WMA Statement on Fetal Tissue Transplantation" (in en-US). https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-statement-on-fetal-tissue-transplantation/.

- ↑ Melanson, Lisa (1 January 1995). "Fetal Tissue Transplantation: An Ethical Approach to Proposed Regulatory Control". Dalhousie Journal of Legal Studies 4. https://digitalcommons.schulichlaw.dal.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1079&context=djls.

|